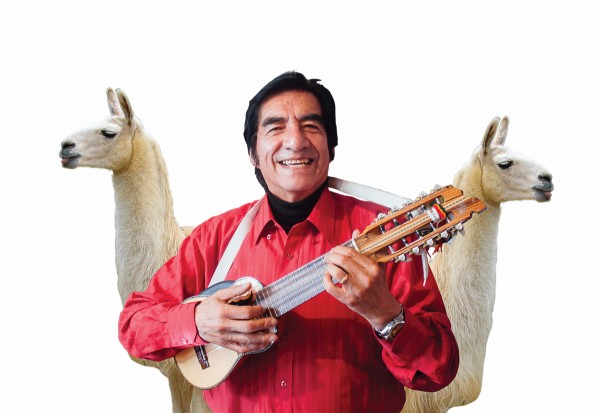

The Unstoppable Pepe Murillo

20 Jul, 2016 | Luke Henriques-Gomes

Photo: Luke Henriques-Gomes

The Peña’s Elder Statesman Reflects on His Storied Past, and Looks to the Future

Ask Pepe Murillo a question about his life, and he responds with a song. In the living room of his two-storey home in Zona Sur with a charango in his calloused hands and three glasses of whiskey on the coffee table for him and his guests, he has a melodic reply to every inquiry.

Murillo, who has rock star status in Bolivia, and has taken his songs to the United States, across Latin America, Europe and Japan, fashions his answers with the same sense of drama you hear in his music – a quiet, pensive bit here, some humour there, and plenty of vulnerability. ‘My mama, she was the biggest influence on my career,’ he says of his music-teaching mother, who has now passed away.

The conversation traverses Murillo’s half-century in the music industry, including his success in Los Caminantes and his involvement with peñas, a type of meeting place for folkloric performances popular in Spanish and Latin American culture.

Murillo’s peña of nearly 40 years, Marka Tambo, on historic Calle Jéan, closed recently due to a lost lease. In his mind, the sort of peñas he remembers from his earliest playing days are few and far between these days.

‘I like it that, when I’m playing, the audience just listens to me,’ Murillo says. There’s a laugh that acknowledges the cheekiness of such a comment, but he’s not joking. He has fond memories of some of the first peñas in La Paz, founded in the ’60s, including one he helped found near Plaza Camacho. It’s now a printer, Murillo says.

‘There was a unique sound,’ he explains. ‘No microphone, and just one small stage to sing that was very close to the audience. These were dedicated to music. Now there are other places where people go to dance. These are different.’

One of these peñas is Gota de Agua, a raucous La Paz establishment that is more like a dance party than a concert. The crowd is almost entirely Bolivian. Couples dance unself-consciously to the hypnotic sounds of Bolivian folk music, both live and recorded, and drink flows freely into mouths stuffed with coca leaves. It’s fun, wild fun.

‘I don’t know the place, but I’d like to see it,’ Murillo says of Gota de Agua. ‘It’s another style, another thing. I really do respect what others are doing.’

Murillo released a new album this year, Todavia Puedo (I Still Can), which sounds like a statement to anyone who doubts his desire to continue. Standing in one of his home’s two rooms of gold discs, giant posters and other memorabilia, he confirms plans to open a new peña, and that another recording will follow next year.

‘Music has always been my life,’ Murillo says, gently strumming his charango. ‘When I play I feel like I’m flying. I have done other things... But music was always the thing I felt most strongly about. I play music to live, I live to play music.’

‘I play music to live, I live to play music.’

– Pepe Murillo