The Titanic Sculptures of Victor Hugo Barrenechea

31 Dec, 1969 | Joshua Neaman

History & Politics and The Arts

Photos: Courtesy or Barrenechea's family

Bolivian and American history set in metal and stone

A new exhibition of the works of Victor Hugo Barrenechea at the Museo de la Revolución in La Paz, the first major retrospective of his work since his death in 2016, confirms the sculptor's place on the highest pedestal of Bolivian arts.

Best known for his large-scale monumental works commemorating great figures and events from across the continent, Barrenechea was born in Sucre in 1929. Art was ever present in the Barrenechea household from Victor Hugo’s earliest years. His father was a notable sculptor in his own right, and helped to nurture his son’s artistic talent. During Victor Hugo’s formative years, his father would become his first and most important mentor, teaching and advising him as he began to explore artistic possibilities and eventually helping him take his first tentative steps down the path to becoming a sculptor.

By his teenage years it was apparent that, under his father’s eye, Victor Hugo had developed a precocious talent for sculpture. However, he also received a formal artistic education, studying at the Academia de Bellas Artes ‘Zacarías Benavides’ in Sucre, and also spending time at a sculpture and pottery school in Cochabamba.

When he was 17, Victor Hugo travelled to La Paz to continue his studies and set up in earnest as sculptor, receiving the patronage of the wealthy Patiño family. At 20 he received recognition for his talents in the form of a national prize and the offer of a scholarship to study in Italy from then Bolivian President Enrique Hertzog.

However, at this point in the trajectory of Victor Hugo’s career, history intervened. Since a defeat to Paraguay in the Chaco War in the early 1930s, Bolivia had been in turmoil as popular dissatisfaction with the criollo elites began to spill out into open opposition. Matters came to a head in 1951 when President Urriolagoitía handed power to a military junta instead of to the opposition Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR), which had just won the elections. This set the stage for a full-scale uprising the following year. In what became known as the Revolución Nacional, the MNR, backed by prominent figures in the police force, overthrew the military in 1952 and began a period of radical reform.

The events of 1952 had a great impact on the young Victor Hugo. The unrest prevented him from going to Europe, but it had a lasting impact on his artistic outlook. It is perhaps fitting that the exhibition displays Victor Hugo’s works in the museum commemorating the Revolución Nacional, since the revolutionary spirit of the time, with its promises of universal suffrage, land redistribution and education reform, provided the key inspirations for his early works, which attempted to express this newfound hope through art. For example, his first major commission, obtained shortly after the revolution in 1952, was the creation of a monument to the miners of Siglo XX, a tin mine in the Department of Potosí, who had played a key role in the opposition to the sexenio.

That work, carried out that year, features a miner standing atop a semicircular mineshaft. One foot is slightly forward and the head is raised, as though the miner is setting out for a distant goal. In his right hand he carries a drill, the symbol of his work, but the left hand carries a rifle raised in a defiant pose, encapsulating the revolutionary fervour of the age. Victor Hugo would later create similar monuments to the miners’ struggle across the country, most notably in Oruro, and develop a reputation as the country’s leading monumental sculptor.

Barrenechea’s sculptures capture a sense of togetherness and national community that underpins a hope for a better Bolivia.

These early works exhibit many of the characteristics that would go on to define the artist’s oeuvre. They are in many ways both forwards- and backwards-looking. As monuments, they commemorate central figures in Bolivian history, celebrating their role in history, but do not serve as mere paeans to a dead past. Instead, they capture a sense of togetherness and national community that underpins a hope for a better Bolivia.

This goes beyond a political ideology to reflect Victor Hugo's strong sense of public duty, a desire to create art not only for art’s sake but to give something back to his country and help bind it together. ‘He lived for his work,’ his daughter María Julia said. This was even seen in his conduct towards others. ‘He was a just man,’ she remembers, recalling how he would always look out for his workers, ensuring they received a fair share of the proceeds from a sculpture and making sure that when they left his service they had enough to live off of.

His children also describe his highly meticulous approach to his art. Hugo Barrenechea Cueto, his older son, remembers Victor Hugo as a man ‘with a really close attention to detail.’ Having received a commission, he would spend months carrying out a minute analysis of his subject, voraciously reading to build up a complete picture of their life and background and then going into the field to make sketches and plans for every aspect of the sculpture. This is reflected in the subtle manipulations of lines and contours that radically alter the expressions of his subjects, breathing life into the busts on display. Meanwhile, clothes are rendered so expertly that, although in the bronze, they seem to retain their natural texture and dynamism.

In an anecdote that perfectly captures the power that his sculptures had to enthral and inspire, Hugo recalls that one night burglars managed to break into his father’s workshops. Though the sculptures themselves were too heavy to steal, the thieves made off with anything portable they could find, including all the tools in the room. However, so impressed were they by the art they saw that before making their escape they paused to scrawl on the wall in large letters ‘good work.’

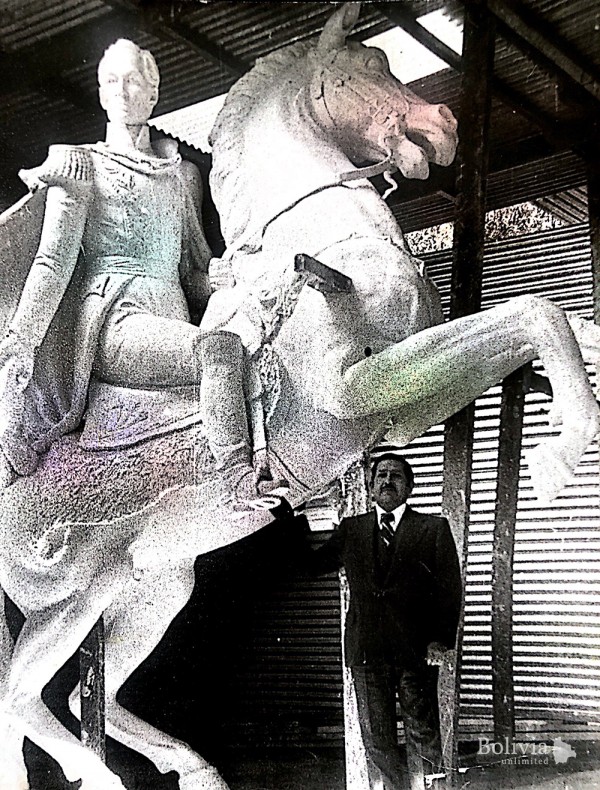

The exhibition also sheds light on the practical processes involved in creating great monuments. The works on display are drawn from all stages of the creative process. There are small-scale models used to give preliminary outlines of the final works, and larger creations in plaster that represent an experimental phase, as moulds were shaped and reshaped by Victor Hugo’s expert hands, making what Hugo called ’small tweaks through which he was able to give life to his works’. Lastly there are full-scale bronze busts, such as those of el Libertador Simón Bolivar and Chaco War hero Germán Busch.

The whole process, from the preliminary miniature models to the creation of the finished product in the foundry, was overseen by Victor Hugo himself. He even took a special course in metalwork so he could participate in the final casting of his statues. As Hugo said, ‘He made his works piece by piece.’ From start to finish, one statue could take up to six months of dedicated work – ‘for equestrian statues, sometimes a year.’

Barrenechea bequeathed a great legacy to his country, both in the form of his ‘titanic work’ and the skills he passed on to his many pupils.

Many of the works on display are merely composite parts of even larger works now displayed in public places. For example, the bust of Simón Bolivar is in fact part of a giant equestrian statue that exists in three separate versions in Caracas, San Francisco and Quebec, a testament to the international reputation of its sculptor. Indeed, Victor Hugo was so renowned that even in 1976 when the sculpture was made, at the height of a violent military dictatorship, he continued to receive commissions for works that, though devoid of their earlier revolutionary symbolism, continued to memorialise the great figures of Bolivian history.

As he grew older Victor Hugo maintained his passion for sculpture. ‘Even in his later life he was still making his sculptures,’ Hugo said. ‘He felt alive when he was working, it was part of his life.’ This passion was transmitted to his children – Hugo, María Julia, Marco Antonio, Miguel Ángel, Norma Rebeca and Harolod Rodolfo – who learned about the art of sculpture as they were growing up, while Victor Hugo’s wife helped him with the administrative part of his work. Although he passed away in 2016, he bequeathed a great legacy to his country, both in the form of his ‘titanic work’ and the skills he passed on to his many pupils, whom he taught at the Academia de Bellas Artes.

For more information about the conservation of Victor Hugo Barrenechea's work, call 591-70673300 or 591-72561700, or write to danielasaraimurillo@hotmail.com