THE OLD GUARD OF BOLIVIAN TROTSKYISM / LA VIEJA GUARDIADEL TROSKISMO BOLIVIANO

31 Aug, 2021 | Charles Bladon

Photo: Dayme Paymal

ENGLISH VERSION

Since 1825, there have been 88 governments in Bolivia, with an average of 2.2 years per government. Chronic political instability has become somewhat intrinsic to the country over the past century with modern Bolivian history seeing the people take matters into their own hands to produce change. Irrespective of their alliance, be it with worker unions, the petty bourgeoisie, intellectuals or the military, people have strived for change. Bolivia’s political landscape has been transformed by the 1952 National Revolution and the military coups that plagued the mid- to late 20th century. An ideology that played a central role in the 1952 National Revolution is the Marxist doctrine imported from the 1917 Russian Revolution that profoundly influenced Bolivian politics throughout the last century.

Trotskyism, the doctrine of the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, has had an especially influential role in the guidance of Bolivia’s political direction. Manuel Gemio, a Bolivian Trotskyist, intellectual and expert in economics and planning, tells me, ‘The role of Trotskyism in Bolivia is very important. It transcends its history. You can’t understand the history of Bolivia without Trotskyism.’ In the past century, the arrival of political parties such as the Partido Obrero Revolucionario (POR) introduced Bolivia to Trotskyism in 1935 (before communism arrived in the 1950s) and helped garner support for the 1952 National Revolution, changing the face of Bolivia’s politics.

Trotsky was assassinated 12 years before the 1952 National Revolution, but his belief that workers should determine the direction of progress in society resonated in the hearts of Bolivian workers. This, coupled with the theory of permanent revolution and the notion that socialism cannot truly work unless it is enacted globally, is the foundation of a Bolivian Marxist doctrine known as the Theses of Pulacayo. The Theses of Pulacayo was Bolivia’s guidebook to Trotskyism and laid the foundation for revolutions to come. It was established by a federation of miners in 1946, with Guillermo Lora – the poster boy for Trotskyism in Bolivia – among them.

The 1952 National Revolution initiated the nationalisation of the mines, introduced land reform and allowed for universal suffrage, three important principles of the workers’ movement. This was a fight started by the Bolivian bourgeoisie in alliance with the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR). But the revolution was virtually on its knees when a coalition between miners, the MNR and the POR saved the movement. The miners stormed the capital alongside armed civilians and successfully sieged La Paz, emerging as heroes of the revolution.

Although the revolution was saved, the consequences of these events were a huge failure for the POR. MNR only used the alliance to build support for its cause, ignoring the POR after seizing power. The POR thereafter declined due to a split among members who supported the MNR and those who didn’t, as well as competition from other left-wing parties that introduced Marxist doctrines, such as Maoism and Marxism-Leninism. The failures of the Guevarista guerillas in the 1960s further weakened their position.

Today, these hardened Trotskyists have been overshadowed by Evo Morales and the incumbent Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), a party that claims to be of the same Trotskyist heritage and where many Trotskyists of the old guard have moved. Although MAS draws on socialist policies, the active members of POR aren’t convinced. At the POR’s centenary celebration of the Russian Revolution, various worker representatives made this view clear. ‘What has the Indio [Evo] done?’, an Aymaran farmers’ union representative yelled, convinced of the limited impact of Morales’s time in office. ‘He has made it worse, he brought hunger and despair,’ he continued. The MAS rose from the ashes of the Sánchez de Lozada government, which brutally suppressed coca farmers, miners and indigenous people. The MAS attained power with the help of workers’ unions that had more than half a century of experience. The current government is seen by some as revolutionary, but the old leftist guard isn’t satisfied.

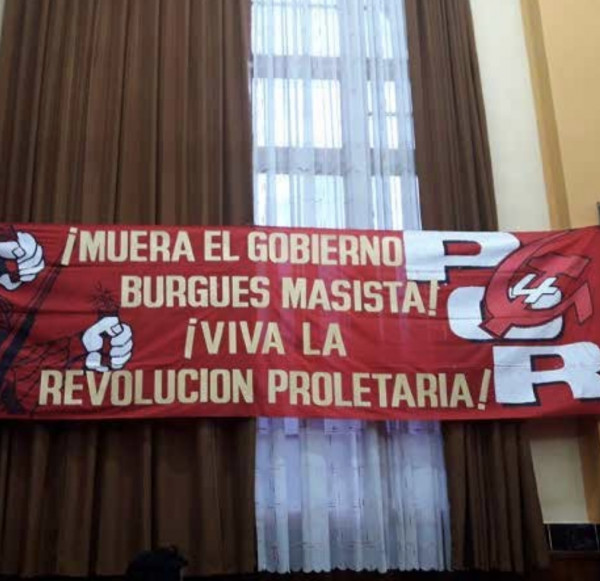

Outcry was rife at a recent event commemorating the centenary of the Russian Revolution. The scene was awash with adoration for Lenin, Trotsky and the iconic Guillermo Lora, their figures immortalised in banners. Farmers, miners and industrial workers alike loudly voiced their dismay towards the MAS government. Further discontent was evident in the blood-red banners calling for the forceful resignation of ‘socialist pretenders’. ‘We will fight for democracy,’ a miner said on stage, ‘fight against the oppression and the lies!’ People in the crowd raised their fists and sang the party’s anthems. However, despite the apparent unity and crowded attendance at the event, the POR is a party whose base comprises ageing academics, plays no political role today, hasn’t managed to renew itself, and still parrots Trotsky’s very same words.

The POR is certain of its goals (which haven’t changed since 1935 and include seeing Trotskyism come into fruition, following the example of the Bolshevik Revolution), but it is unclear whether the party can actually achieve them. With a question mark looming over the organisation, its lack of new, younger members provide an eyehole into its future. According to Jamie Jesus Grajeda García, executive secretary of a local student federation, today’s youth does not take much of an interest in politics. ‘The issue is that young people are more focussed on themselves than on the betterment of the country,’ Grajeda says. The global trend of diminishing youth engagement in politics is disconcerting for the POR. In the past, the party’s support network was made up of workers and Bolivian youth impassioned by the plea for change. But that support is dwindling.

Whilst the party often questions its future, it remains unquestionable that POR’s original objective, its permanent fight to revolutionise the system, is the only thing that keeps it alive. This mood of disgruntledness resonating from the theatre halls hosting the party’s conferences was well-timed. With Evo Morales pushing his reelection as MAS’s presidential candidate, a call for revision and change is prudent due to the discontent sowed by the familiar foe of past authoritarianism. Moreover, this period coincides with a centenary which acts as a time of reflection and a moment to look back at the Russian Revolution as an example. For old-school Trotskyists, it was also a time for envisioning an epic comeback for the party, like ‘the aged bear’ that revived and became a powerhouse for the people – a vision that ensnares the hopeful workers of Bolivia who still feel so hopelessly disenfranchised.

-------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Desde 1825, ha habido 88 gobiernos en Bolivia, con un promedio de 2,2 años por gobierno. La inestabilidad política crónica se ha vuelto algo intrínseca al país durante el siglo pasado, y la historia moderna de Bolivia ha visto a la gente tomar el asunto en sus propias manos para producir cambios. Independientemente de su alianza, ya sea con sindicatos de trabajadores, la pequeña burguesía, intelectuales o militares, la gente ha luchado por el cambio. El panorama político de Bolivia ha sido transformado por la Revolución Nacional de 1952 y los golpes militares que asolaron desde mediados hasta fines del siglo XX. Una ideología que jugó un papel central en la Revolución Nacional de 1952 es la doctrina marxista importada de la Revolución Rusa de 1917 que influyó profundamente en la política boliviana a lo largo del último siglo.

El trotskismo, la doctrina del revolucionario ruso León Trotsky, ha tenido un papel especialmente influyente en la orientación de la dirección política de Bolivia. Manuel Gemio, un trotskista boliviano, intelectual y experto en economía y planificación, me dice: “El papel del trotskismo en Bolivia es muy importante. Trasciende su historia. No se puede entender la historia de Bolivia sin el trotskismo. '' En el siglo pasado, la llegada de partidos políticos como el Partido Obrero Revolucionario (POR) introdujo a Bolivia al trotskismo en 1935 (antes de que llegara el comunismo en la década de 1950) y ayudó a obtener apoyo. para la Revolución Nacional de 1952, cambiando el rostro de la política boliviana.

Trotsky fue asesinado 12 años antes de la Revolución Nacional de 1952, pero su creencia de que los trabajadores deben determinar la dirección del progreso en la sociedad resonó en los corazones de los trabajadores bolivianos. Esto, junto con la teoría de la revolución permanente y la noción de que el socialismo no puede funcionar verdaderamente a menos que se promulgue globalmente, es la base de una doctrina marxista boliviana conocida como las Tesis de Pulacayo. Las Tesis de Pulacayo fue la guía de Bolivia para el trotskismo y sentó las bases para las revoluciones venideras. Fue establecido por una federación de mineros en 1946, con Guillermo Lora, el chico del cartel del trotskismo en Bolivia, entre ellos.

La Revolución Nacional de 1952 inició la nacionalización de las minas, introdujo la reforma agraria y permitió el sufragio universal, tres principios importantes del movimiento obrero. Esta fue una lucha iniciada por la burguesía boliviana en alianza con el Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR). Pero la revolución estaba prácticamente de rodillas cuando una coalición entre los mineros, el MNR y el POR salvó el movimiento. Los mineros irrumpieron en la capital junto con civiles armados y sitiaron con éxito La Paz, emergiendo como héroes de la revolución.

Aunque la revolución se salvó, las consecuencias de estos hechos fueron un gran fracaso para el POR. El MNR solo usó la alianza para generar apoyo para su causa, ignorando al POR después de tomar el poder. El POR a partir de entonces declinó debido a una división entre los miembros que apoyaban al MNR y los que no, así como a la competencia de otros partidos de izquierda que introdujeron doctrinas marxistas, como el maoísmo y el marxismo-leninismo. Los fracasos de las guerrillas guevaristas en la década de 1960 debilitaron aún más su posición.

Hoy, estos trotskistas endurecidos han sido eclipsados por Evo Morales y el actual Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), un partido que dice ser de la misma herencia trotskista y donde se han movido muchos trotskistas de la vieja guardia. Aunque el MAS se basa en políticas socialistas, los miembros activos del POR no están convencidos. En la celebración del centenario de la Revolución Rusa por parte del POR, varios representantes de los trabajadores dejaron claro este punto de vista. "¿Qué ha hecho el Indio [Evo]?", Gritó un representante del sindicato de agricultores aymara, convencido del impacto limitado del tiempo de Morales en el cargo. "Lo ha empeorado, ha traído hambre y desesperación", continuó. El MAS surgió de las cenizas del gobierno de Sánchez de Lozada, que reprimió brutalmente a los cocaleros, mineros e indígenas. El MAS llegó al poder con la ayuda de sindicatos de trabajadores que tenían más de medio siglo de experiencia. Algunos ven al gobierno actual como revolucionario, pero la vieja guardia de izquierda no está satisfecha.

Las protestas abundan en un evento reciente que conmemora el centenario de la Revolución Rusa. La escena estaba inundada de adoración por Lenin, Trotsky y el icónico Guillermo Lora, sus figuras inmortalizadas en pancartas. Agricultores, mineros y trabajadores industriales expresaron en voz alta su consternación hacia el gobierno del MAS. El descontento se hizo evidente en las pancartas rojo sangre que pedían la renuncia enérgica de los "pretendientes socialistas". "Lucharemos por la democracia", dijo un minero en el escenario, "¡lucharemos contra la opresión y las mentiras!" La gente de la multitud levantó los puños y entonó los himnos del partido. Sin embargo, a pesar de la aparente unidad y la concurrencia masiva al evento, el POR es un partido cuya base está formada por académicos envejecidos, no juega ningún papel político hoy, no ha logrado renovarse y sigue repitiendo las mismas palabras de Trotsky.

El POR está seguro de sus objetivos (que no han cambiado desde 1935 e incluyen ver cómo el trotskismo se materializa, siguiendo el ejemplo de la revolución bolchevique), pero no está claro si el partido realmente puede alcanzarlos. Con un signo de interrogación que se cierne sobre la organización, su falta de miembros nuevos y más jóvenes proporciona una oportunidad para ver su futuro. Según Jamie Jesus Grajeda García, secretario ejecutivo de una federación de estudiantes local, la juventud de hoy no se interesa mucho por la política. "El problema es que los jóvenes están más centrados en sí mismos que en la mejora del país", dice Grajeda. La tendencia global de disminuir la participación de los jóvenes en la política es desconcertante para el POR. En el pasado, la red de apoyo al partido estaba formada por trabajadores y jóvenes bolivianos apasionados por el llamado al cambio. Pero ese apoyo está disminuyendo.

Si bien el partido a menudo cuestiona su futuro, sigue siendo incuestionable que el objetivo original del POR, su lucha permanente por revolucionar el sistema, es lo único que lo mantiene vivo. Este estado de ánimo de descontento que resuena en las salas de teatro que albergan las conferencias de la fiesta fue oportuno. Con Evo Morales impulsando su reelección como candidato presidencial del MAS, es prudente hacer un llamado a la revisión y al cambio debido al descontento sembrado por el conocido enemigo del autoritarismo pasado. Además, este período coincide con un centenario que actúa como un momento de reflexión y un momento para mirar atrás a la Revolución Rusa como ejemplo. Para los trotskistas de la vieja escuela, también fue un momento para imaginar un regreso épico para el partido, como 'el oso anciano' que revivió y se convirtió en una potencia para el pueblo, una visión que atrapa a los trabajadores esperanzados de Bolivia que todavía se sienten tan desesperados. privado de sus derechos.