Reinaldo Chávez Maydana

21 Jun, 2018 | Marion Joubert

Image: Courtesy of Reinaldo Chávez Maydana

Combining Bolivian tradition and mystic symbolism, the artist captures the sublime

How can three simple dots – two for the eyes and one for the mouth – express so many different emotions? You might ponder this question yourself once you take a close look at the artwork of La Paz artist Reinaldo Chávez Maydana.

His paintings catch my attention because of a particular facial expression I notice in many of them. I ask Chávez about this. He explains that the figures are whistling. ‘They do it because they are happy,’ he says. The paintings I’m looking at represent the traditional Bolivian diablada dance. But those three dots that enthrall me are taken from El día de los muertos, an event which takes place on 1 November. For this holiday, which honours the dead, bakers make bread loaves in the shapes of many different figures. As a child, Chávez thought these figures were alive, with three dots for the eyes and the mouth. Now he incorporates this technique into his art, separating the faces with a line. Why this division? Chávez believes that contrasts are everywhere. ‘Night and day, good and evil, man and woman,’ he says. ‘This complementariness exists in human beings, in everything that exists in the world.’

‘I paint what I want, what impassions me.‘I paint because I love it.’

—Reinaldo Chávez Maydana

Our conversation goes on, and we discuss his abundant use of symbols. The majority of them, Chávez says, come from iconic elements of Bolivian culture, such as the masks from the morenada dance. I look at his paintings and I think I see Bolivia's soul in them—and I’m apparently not the only one to notice this. Organisers have recently asked Chávez to create a 70-metre-long fresco for La Paz’s iconic Gran Poder celebration.

But Chávez doesn’t just borrow from Bolivian traditions; he’s creatively inspired by many other things. He recently created a 40-part art cycle. His themes are various: pregnancy, women's sensuality, children, birds, landscapes and societal issues such as migration. He’s inspired by anything that gives him an emotional response, which he transmits through his art.

Chávez says his mother introduced him to this ‘magic world of colours’ at the age of 7, and his style has never stopped evolving by what affects him in his life. Discussing his art, he says, ‘You need to provoke something with your paintings. Art is not just about techniques or concepts, it's about emotions and feelings.’ Chávez says it was difficult, after attending art school at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, to break the rules he learned in order to be spontaneous in his work. His creative process is simple: He doesn't make any drafts, starting with a certain idea but remaining flexible with its execution. He might start to draw a couple, but if the shapes are different from his original idea, the painting could end up being a depiction of a child playing. He paints unpredictably, with passion. The strongest feeling which gives him inspiration to create, he says, is pain. ‘When you are happy,’ he says, ‘your passions go in other directions, to other people and activities.’

But that doesn’t mean he’s sad while painting. As an example, Chávez says that when creating a folklore-influenced piece, he’ll listen to traditional music and remember his grandfather, who used to dance at Gran Poder. He says he attains a feeling of freedom while creating his art. ‘I paint what I want, what impassions me,’ he says. ‘I paint because I love it.’

Chávez paints first for himself, he says, not the individuals who buy his work. His fans are Bolivians, but foreigners interested in unique folklore souvenirs from Bolivia have also noticed him. His art has travelled the world since 1998, with 30 exhibitions here and in the United States, Mexico, Argentina and Peru.

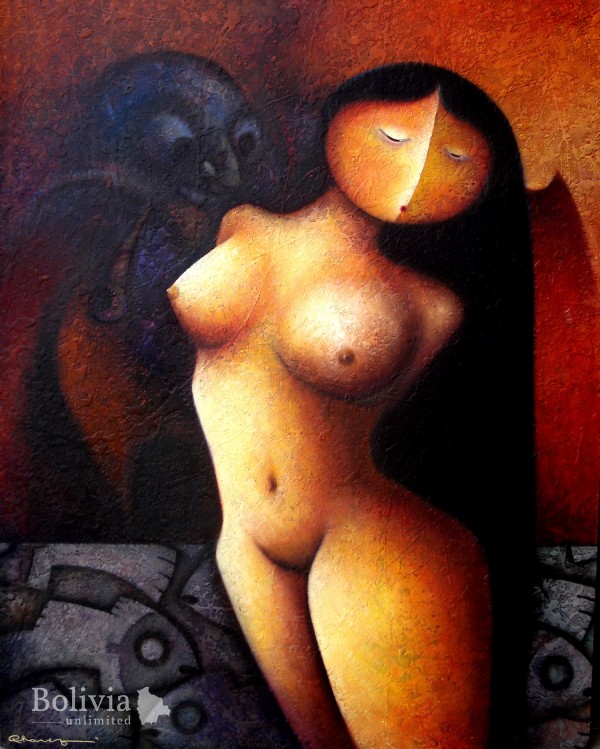

There’s one piece, though, that Chávez will not sell, that he keeps for his gallery. From his Flores desnudas series, it’s displayed at his gallery on Calle Sagarnaga. It explores folklore, sensuality, pregnancy and abortion, which is illegal in Bolivia.

Two figures, each depicted quite differently, dominate the painting. The first is a beautiful naked woman, exuding femininity and lost in thought. The other figure looks like a dangerous daemon, full of lust and looking like he wants to possess the woman. This painting, Chávez says, was inspired from stories about the morenada.

His artwork is a mixture of reality and imagination, while symbolising something deep and ethereal.

There’s a tragic backstory to the painting. A year and a half after the the painting was finished, the model who portrayed the woman died. Thus Chávez’s creation has a tragic side, giving it more depth, and it’s a way to pay tribute to his late muse. And it epitomises Reinaldo Chavez Maydana's style (even if he professes not to have one): a mixture of reality and imagination, while symbolising something deep and ethereal.

26 Jun, 2018 | 16:19