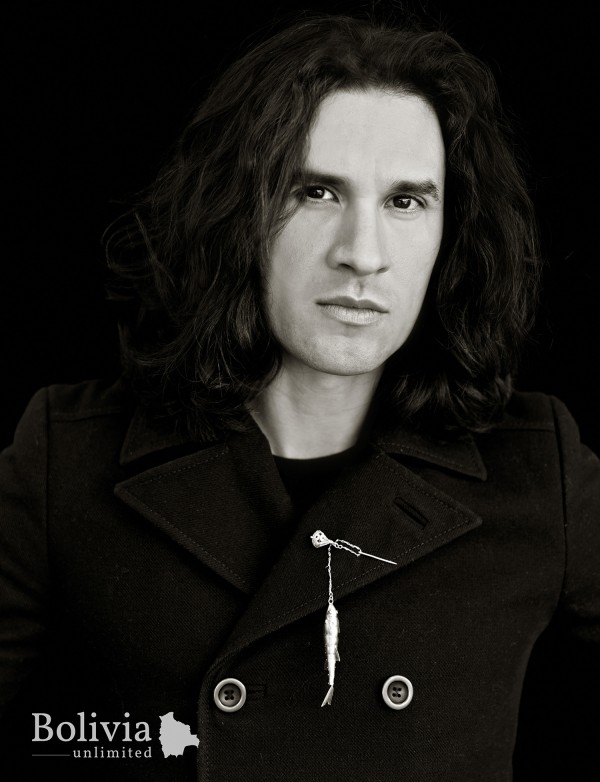

Joaquín Sánchez

23 May, 2018 | Niahm Elain

Photo: Gabriel Barceló

The artist bringing the country’s culture to the forefront of Bolivia’s art scene.

Last month, the Mérida Romero gallery in La Paz’s Zona Sur neighbourhood was home to the work of famed Paraguayan-Bolivian artist Joaquín Sánchez. His art has been shown in galleries, museums and exhibition spaces all over the world, from France to Australia as well as almost every country in South America. This particular exhibition, spanning over 10 years of his work, allowed gallery-goers to gain insight into the artist’s rich and varied oeuvre. Just as Sánchez’s body of work focuses on how things change over time and the relationship they maintain with their past, the way in which the artist’s work has evolved over the years is as evident as the aspects which unite each new piece or project.

Born in 1977, Sánchez was raised in the Paraguayan countryside during Gen. Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship (1954-89). His family frequently moved around as his grandfather was the proud owner of a mobile cinema, something which sparked Sánchez’s interest in film. But Sánchez, a multimedia artist who speaks Spanish and Guaraní, the indigenous Paraguayan language, uses video in addition to sculpture and photography. This fusion of methods and media derives from the fact that he comes from ‘a unique territory, an amorphous frontier between two countries,’ he says. ‘I’m very aware of my mestizo condition, as well as being bilingual. For me, nothing is pure, and so I must use different languages and resources to express myself and my ideas.’

Growing up during such a turbulent time during his childhood in Paraguay – and of course living in Bolivia as of late – Sánchez is naturally preoccupied with politics. His artistic themes often revolve around both countries’ social and political landscapes. ‘My artwork arises from a kind of conflict, whether sociopolitical or cultural and personal,’ he says. ‘And this is expressed through a story, which comes to me either in the form of words or images that tell a certain tale.’ Traces of his birthplace’s influence can be seen in works such as Corazón de Ñandutí, a diagram of a heart encased in glass and rendered in traditional Paraguayan embroidered lace. A nod towards his concern for Bolivian politics is his installation and photographic work involving polleras, the skirts worn by cholitas paceñas, spread like wings on the dusty altiplano ground and scattered with freshly dug-up potatoes.

Sánchez’s work not only deals with two countries and their two respective cultures, but with two periods of time, too. He’s fascinated by the interface between the past and present, the ancient and the modern. This is clear in Sánchez’s tendency to combine and juxtapose history with popular culture. The ‘omnipresence of the natural landscape,’ as he says, enchants him, the way in which the past is so close to the surface in old buildings and rugged, rural settings. In ILLA 1, Sánchez places an enormous, inflatable gold bull on top of a thatched-roof cottage somewhere in the Bolivian altiplano. The contrast between the evident remoteness of the hut and its crumbling cow shed and the gaudy, pop-art bull – which has a hint of Jeff Koons’ tongue-in-cheek absurdity (Koons’ Balloon Dog comes to mind) – references the artist’s desire to ‘erase and rewrite the past, rescue near-forgotten stories in order to return them to the future, injecting them with new, fictitious elements to give old facts a poetic spin.’

The way in which the form of objects can morph over time but still carry historical remnants, and thus memories, fascinates the artist. Whether by placing latex-balloon animals on stacks of hay, making bodily organs from wool or carved wood, or photographing pieces of clothing but not the humans that should be wearing them, Sánchez draws much attention to disparity and absence. And, in doing so, he depicts a country’s unique culture by engaging with the present while simultaneously exploring the past.