Jiwasa

11 Dec, 2019 | Anneli Aliaga

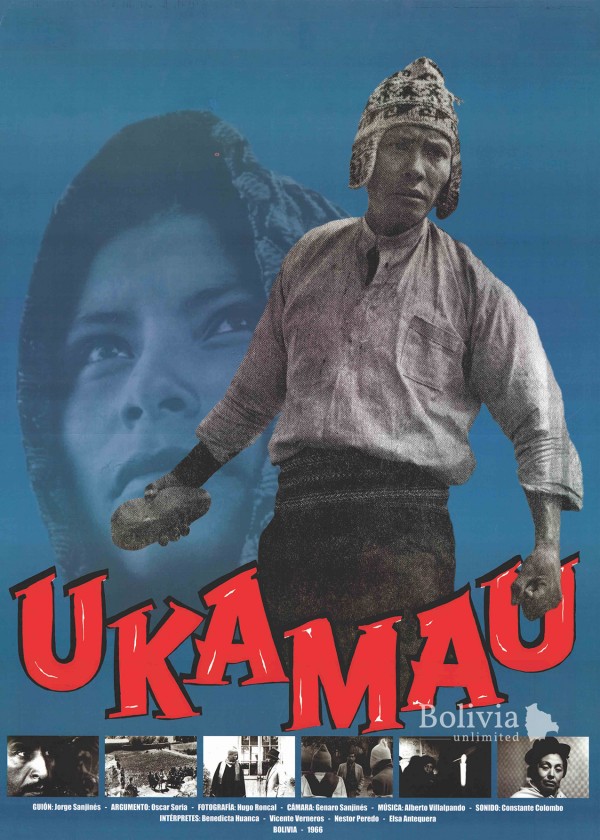

Photos: Courtesy of Fundación Grupo Ukamau

The continuing legacy of Jorge Sanjinés and the Grupo Ukamau’s combative cinema

It is impossible to think and speak about Bolivian cinema without mentioning film director Jorge Sanjinés and the Grupo Ukamau, the cinema group he founded. Sanjinés’s 1966 film Ukamau was the first feature-length Aymara-language film, and it lent its name to the group. In Aymara, ukamau means ‘it’s like this’. The word strongly resonates with the group’s political Marxist commitment to exposing national socio-political realities to Bolivian citizens and fearlessly denouncing imperialist crimes against Bolivia’s indigenous communities. César Pérez Hurtado, one of the founding members of Ukamau and the director of photography and camerawork for its most iconic film, La nación clandestina (1989), explains that Ukamau’s films are a ‘service to the country’. Sanjinés’s devotion to and representation of the cosmovisión andina has made him one of the most celebrated patrons of the indigenous people of Bolivia.

What started off as a small gathering of Bolivian film intellectuals wanting to improve the social conditions of marginalised ethnic populations grew to become one of the leading participants in the New Latin American Cinema movement of the 1960s. This cinema movement was initiated in response to the extensive struggles associated with the underdevelopment that plagued Latin American nations. This revolutionary type of cinema used film as a political tool. It empowered popular sectors by giving them a platform and broadcast the injustices happening on the continent to other corners of the world. In the case of Sanjinés and Ukamau, their cinematographic and political agenda correlated perfectly with this movement’s ideals. Sanjinés adopted an inherently combative social cinema to shape the lived realities of the Quechua-Aymara peasantry of Bolivia.

From the moment the Grupo Ukamau began producing films, such as Yawar Mallku (1969) and El coraje del pueblo (1971), its members sought to simulate a different point of view from that shown in mainstream Westernised cinema. Ukamau member Pedro Lijeron says that Ukamau’s films presented ‘a new point of view, of another world, to a universal audience.’ In Sanjinés’s films, heroes and protagonists are indigenous Andean people. When asked to summarise the philosophy of the cinema group, Pérez responds, ‘We think of others before ourselves.’ Lijeron simply says, ‘Ukamau, junto al pueblo’ (‘Ukamau, with the people’). Both their answers confirm how Ukamau was created on the basis of defending those most in need and giving these sectors a voice and a space through cinema.

Unfortunately, Ukamau’s films are extremely difficult to view on DVD or online. Sanjinés ensured that his cinema could only be watched at film screenings, as a collective experience. Ukamau’s philosophy also revolves around ideas of unity and collectivity. Pérez describes the deeply fissured state that was Bolivia when the group was founded. ‘Urban citizens and intellects used to speak about “Otherness”,’ he says. ‘But I had to ask myself, “What is Otherness?” The truth was, it was the indigenous people that were forever living in marginality of what was happening in Bolivia.’ Pérez feels that this segregation was unnatural to the native and modern cultures of Bolivia. ‘In La Paz, we always speak in first person plural: iremos, nos tomaremos, etc. Always in plural,’ he says. If Pérez were to reduce Ukamau’s philosophy to one word, he says he would choose jiwasa, meaning ‘we’ or ‘us’ in Aymara. Ukamau’s films are for, from and with the people of Bolivia.

It must be noted that the Grupo Ukamau’s work and efforts are not stuck in the past. Its cinema lives on. Sanjinés and Hurtado are still active on the cinema scene and have been joined by a new generation of filmmakers to continue the legacy of Ukamau. Hurtado and Ligeron both agree that while the group is still devoted and committed to representing the popular sectors, it has opened up a new space for progress, one that simultaneously looks to the future and reflects on and analyses the country’s past. The group’s latest films, such as Insurgentes (2012) and Juana Azurduy (2016), are feature-length dramas that draw on significant historical events and figures that allow Bolivians get in touch with their roots and understand their current realities. In a similar vein, the upcoming movie Los viejos soldados (due to come out in 2020) tells the story of a friendship between an indigenous Aymara farmer and an urban white Bolivian during the 1932–35 Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay. Ligeron also comments on how important it is that Ukamau has opened up a new space for dialogue and filmmaking by inaugurating the Escuela Andina de Cinematografía. Sanjinés started the school for aspiring filmmakers to create audiovisual material in order to ‘collaborate towards the construction of a more democratic and participatory society.’ The director and the Grupo Ukamau have had an unprecedented positive social effect on improving the lives of the indigenous peoples of Bolivia, and their mission is still not over.

To learn more about Fundación Grupo Ukamau visit or their instagram @fundaciongrupoukamau