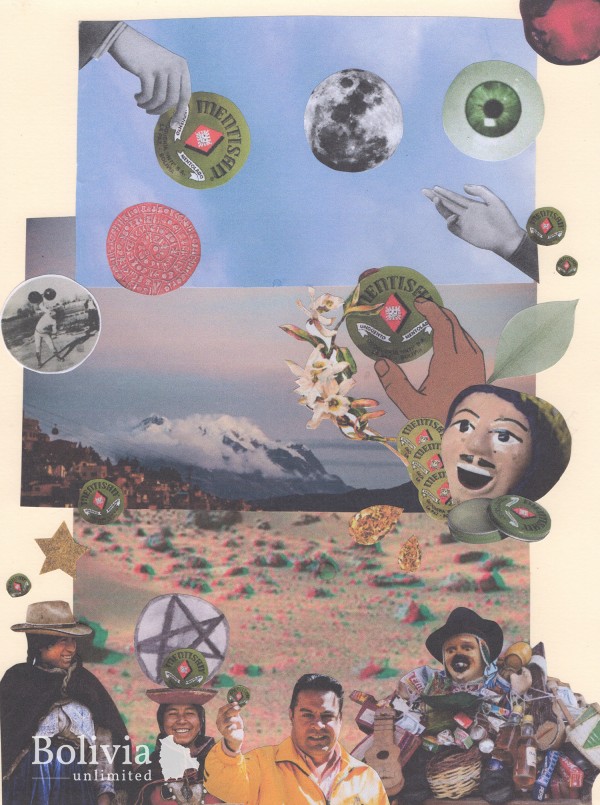

Happy Birthday, Mentisan!

23 May, 2018 | Niahm Elain

Images: Niahm Elain

Bolivia’s beloved balm is turning 80

A tin of Mentisan is as common in a Bolivian household as a bible in a hotel room. The menthol ointment was invented here back in 1938, which is why this special Bolivian concoction is turning 80 this year. Taking a queue from its name, a combination of ‘menta’ (mint) and ‘sanar’ (to heal), this product does exactly what it says on the tin. Actually, it does a little more than that too.

Its German inventor, Ernesto Schilling, migrated to Bolivia in the 1920s. His aim was to create a product that would alleviate the symptoms of the common cold, an illness that is rife in the Andean altiplano; and what he came up with has certainly been successful. Massaged directly onto the chest or onto sore, rubbed-raw noses, or vaporised to decongest the respiratory tract, Mentisan’s effectiveness made it an instant hit in the country. Not long after its conception, Bolivians started using the ointment for other ailments. The cherished product is now used to calm rheumatic as well as neuralgic pains, and to relieve burns caused by flames and sun rays alike. It’s also said to have the power to heal insect bites, moisturise cracked heels, and even fade bruises. In short, it serves as a multi-purpose, miracle, cure-all product.

Its healing abilities are so well-known here that, although it is sold on a prescription-free basis, even doctors recommend Mentisan as a kind of home remedy. ‘People know that Mentisan cures everything and that if they apply it, everything will be OK,’ claims Ronald Gutierrez, who works at the business department of Inti Laboratories, the sole manufacturer of the product. According to Gutierrez, since the ingredients of Mentisan are all natural, you can even use the paste on an open wound. It may not heal the wound, he says, but it won’t aggravate it either. In its long history producing Mentisan, Inti Laboratories has never received a formal complaint about the product failing to deliver the palliative results it promises. The only issues that have emerged in the past involved people who were having trouble opening the tin container. With the can’s new design, however, it’s even easier now for people to get their hands on, and fingers in, the stuff.

Given Mentisan’s success in the Bolivian market, there have been attempts to launch knock-off products in the country. There was once a reddish-tinted Chinese ointment circulating in the pharmaceutical market and there is, of course, the commercial giant, VicksVapoRub. But both threats were short-lived. ‘Vicks’, and other similar products fail utterly to enter the Bolivian market because Bolivians are already so committed to Mentisan,’ says Gutierrez. Inti’s only factory, situated in El Alto, is exclusively dedicated to producing the balm and manufactures around six million units annually. Some of them are exported to Peru, Germany, Macau, the United States, and Denmark. The rest are sold in pharmacies and supermarkets across Bolivia.

So, what’s the winning formula? Emollient petroleum jelly, to soothe and hydrate; essential oils of eucalyptus and pine, to calm and clear the throat; and menthol, which works as a light antibacterial. Despite being well into retirement age, Mentisan’s recipe has barely changed over the years. Perhaps it is the recipe’s simplicity that makes Mentisan such an effective and timeless product. Quality and consistency are the most important factors in Mentisan’s production, says Gutierrez, meaning Bolivians come back to it time and again. It’s dependable, like a backbone. But slippery.

Since Bolivians were frequently using Mentisan as a lip balm Inti Laboratories released an 8g tube applicator designed especially for this purpose. The lip balm container now appears alongside the tiny 15g and 25g tin containers, but they all contain the same stuff. The underpinning philosophy of ‘if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it’ has also been applied to Mentisan’s seemingly unwavering branding. The alterations that have been made to its distinctive logo and complimentary colours have been only to adapt the product for sale in foreign markets. The tin sold in Germany, for example, has a more clinical appearance: a dentist-chair turquoise is separated from a marine blue background with a white toothpaste-stripe, curved in the shape of a nose in profile. But the Bolivian packaging doesn’t need to be so suggestive of its pharmaceutical benefits since they are already common knowledge. Indeed, keeping the packaging similar to the original only consolidates the staple product’s status as a national treasure. It is as charmingly familiar – and stubbornly unchanging – as an old relative. And just as loved.