According to the 2017 Global Innovation Index, Bolivia ranks 106th (Switzerland ranks 1st), making it the last South American country to appear on the list. This index, elaborated jointly by Cornell University, the INSEAD Business School and the World Intellectual Property Organisation, looks at 130 world economies taking into account a dozen parameters such as government expenditures in education and research-and-development investment. Bolivia ranking low on the list can be viewed as demoralising, but it also means that there is only progress to be made. One need only to look around to see the country’s potential.

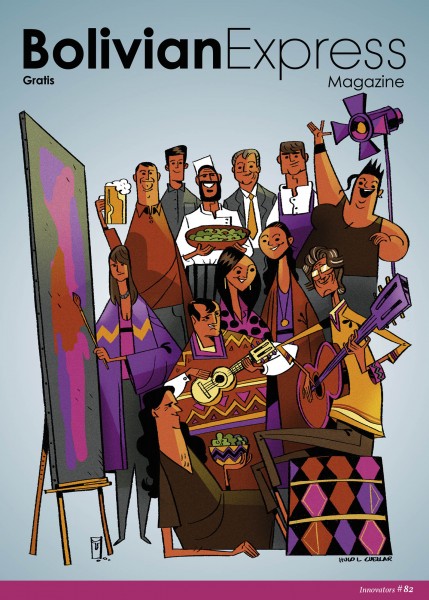

I mentioned in last month’s editorial how a mentality of mediocrity can hold back both people and nations. A painful history of colonisation, dictatorship and inequality has impeded growth and, until now, hindered innovation. But this is changing. In this issue of Bolivian Express, we have selected 12 innovators, each with an idea and a vision, each thriving to create a new future for Bolivia. Twelve people, all very different, but who have in common the same underlying, indeniable and unwavering passion – a zeal for their work fueled by a profound love for their country.

Included are some that have adopted and embraced Bolivia. Based in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Guido Mühr brought German brewing techniques to Bolivia and created Prost, a new but already very popular beer. From Slovenia, Ejti Stih watched her home country splinter during the Yugoslav Wars and now paints politically-charged art. Stih’s message is brutal – her last series graphically depicts abortion – but only because she wants to be a voice for social change. She is not alone in this: Film director Denisse Arancibia delivers in her movies light-hearted fun with an added layer of provocative social commentary.

Bolivian products are starting to shine; the country has much to offer in diversity and quality. Sebastian Quiroga, head chef of vegan gourmet restaurant Ali Pacha, showcases this in his dishes and the products he uses. And another underappreciated resource that is just beginning to stand out is the coffee from Los Yungas. Mauricio Diez de Medina, coffee enthusiast, is setting out to transform the Bolivian coffee industry. Paul ‘Pituko’ Jove, another entrepreneur we chose to highlight this month, is by day the owner of the vegetarian restaurant Namaste and by night a DJ working on consolidating the electronic music scene in La Paz.

This month, we look at the innovators, entrepreneurs and influencers who are taking Bolivia and Latin America to the next level. There is fashion designer Ericka Suárez Weise and leather-goods creator Bernardo Bonilla, two upcoming talents in Bolivia’s creative scene. But ultimately, education is the key to encourage innovation and improve social conditions. Daniella García, CEO of the Elemental technological school, understands this and wants to empower Bolivian children to embrace and learn how to use technology.

These changes wouldn’t be possible without the influence and impact of Bolivian legends Ernesto Cavour and Matilde Casazola, artists who keep new generations motivated with melodies and words that still resonate today. Here we present you 12 profiles, 12 passions and 12 ways to be inspired.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

Denisse Arancibia Flores, Director and Star of Las Malcogidas

‘In Bolivia, there is no film industry,’ says Denisse Arancibia Flores, director of the 2016 Bolivian musical-comedy film Las Malcogidas (roughly, ‘the badly fucked’). Arancibia, who works as a television editor and graduated with degrees in cinema directing and social communication from the Universidad Católica Boliviana and the Private University San Francisco de Asís, carries a tote with an image of a Stanley Kubrick clapperboard printed on the front. She says that the Bolivian filmmaking community is simply too small to sustain an industry, estimating that the country produced only about five features last year.

‘The most difficult thing is the financing,’ Arancibia says. Making Las Malcogidas took seven years. ‘It’s very difficult to find [funding] because we don’t have state support. This is how cinema usually works elsewhere in South and Latin America. But we don’t have that, and sponsorship or private investment are minimal.’ She says a grant from the Ibermedia programme, an organisation that supports South American filmmakers, enabled her to produce her film.

Las Malcogidas is an intimate character piece that follows Carmen, a 30-year-old in a search of her first orgasm.

It takes strength and passion to make a film in a country with few resources and little infrastructure, but Arancibia, whose neon-red hair and commanding presence provide evidence of the bold and determined personality it takes to achieve such a feat, doesn’t seem to think production itself in Bolivia is as dramatic a challenge. She says that directing is about being a part of something bigger and credits the people she works with for making it happen. ‘There are many people who want an industry,’ she says. ‘There are great actors, great directors of cinematography, and the electricians are ninjas.’ (If you’ve ever seen a Bolivian electrical lineman work, you’ll know what she’s talking about.) ‘In reality, there is a lot of talent [in Bolivia],’ she adds. Arancibia argues that with fewer resources available, this talent is part of what makes filmmaking in Bolivia possible; a lack of capital and materials requires greater creativity on the parts of the cast and crew.

Arancibia’s creative use of resources shines in her work. Las Malcogidas, an intimate character piece, follows Carmen (played by Arancibia), a 30-year-old in a search of her first orgasm. As Carmen struggles to lose weight in order to please her narcoleptic grandmother, she also tries to earn the money her brother (played by Arancibia’s actual brother) needs for a sex-change operation. Arancibia’s sharp, musically comedic writing keeps the audience close to its subjects. The film is set in La Paz, but could be almost anywhere – with only a few, simple locations, Arancibia saves herself the hassle of moving people and equipment from set to set while keeping her story focused on the plot. Her close, efficient use of the frame reduces the work necessary to decorate and construct large sets while keeping her audience focused on the characters’ emotions. While many musicals pull audiences in with extravagant, resource-intensive dance choreography and complex cinematography, Las Malcogidas feels deservedly personal with simple yet engaging orchestration, carefully edited to keep viewers interested without the expensive flash characteristic of big-budget cinematic productions.

What makes Las Malcogidas truly Bolivian, however, are not the circumstances of its production, but rather what its production means for Bolivia. Arancibia says stories set Bolivian films apart. ‘We have very particular stories to tell,’ she says, ‘things [to say] that are very Bolivian.’ In Las Malcogidas, Arancibia’s story, full of characters searching for gratification and acceptance in a world of denial and rejection, presents a clear message: to find fulfillment in life, acceptance of the self is paramount. Arancibia herself appears a confident, articulate testament to this message.

‘[Bolivian cinema] is diversifying. We’re looking to explore. We’re open to possibilities.’

—Denisse Arancibia Flores

‘I have a lot of faith in Bolivian cinema,’ Arancibia says. She has a positive outlook for the future of film in Bolivia and sees potential to continue making movies. It’s clear in her work, too, that Arancibia isn’t the sort of artist to back down from a challenge. In its name alone, Las Malcogidas, while preserving the bold artistic storytelling traditions of her native land, takes a step away from traditionally conservative Bolivian thought and makes it clear that a new generation of Bolivian artistry has something to say. ‘[Bolivian cinema] is diversifying,’ Arancibia says. ‘We’re looking to explore. We’re open to possibilities.’

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

The young entrepreneur is providing science and technology education to Bolivia’s new generation

How can you make a car go from point A to point B using only the power of the wind? This is one of the technological quandaries that children and teenagers aged 7 to 18 are trying to solve in the Elemental technological school, founded in 2016 by Daniella García Moreno, that teaches programming and robotics and prepares students for the jobs of the future.

A systems engineer, entrepreneur and educator, García was featured in MIT Technology Review’s 2016 ‘Innovators Under 35’ list for Paraguay and Bolivia for her work with Elemental, a recognition she received only six months after opening the school. She also received a grant to be one of the selected fellows in the US State Department’s Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative.

Born in Oruro, García studied in Cochabamba at the University of San Simón, where she graduated with a degree in systems engineering. She developed software for eight years before moving to La Paz and founding her school. García’s impetus in creating the Elemental school was to address a problem she had frequently encountered while she was working. ‘There was alway a high demand for technological talent, and they were always looking to hire, but there were never enough qualified professionals,’ García says. ‘I wondered, “What was the problem?” The work environment is good, schedules are good, and we live in a country with high unemployment. So it didn’t make sense.’

‘Generation Z are digital natives. They use the technology like natives, even better than their parents. How is it that education hasn’t adjusted to these needs?’

—Daniella García Moreno

The answer, she found out, was deeply rooted in education and in how technology is not appropriately taught to new generations: ‘Children are not incentivised or exposed to technological areas,’ García explains. ‘We don’t see programming in schools; they [only] use Word, Excel, Powerpoint, and this is very basic,’ García says. ‘Especially since Generation Z, those who are between 7 and 21 years old, are digital natives. They use the technology like natives, even better than their parents. How is it that education hasn’t adjusted to these needs?’

García sees a real potential in the new generation. Her flagship programme, Criados Digitales, bets on that. Through it, teens participate in the Bolivian Olympiad of Informatics. ‘It started as an experiment; [last year] in the departmental competition, we won 80% of the medals, and eight medals on the national level,’ García says. ‘Sixteen children were selected; they were good at maths but had never seen programming before. And we took them from not knowing anything about programming to winning medals in seven months.’

Which is why, García says, it’s essential to stimulate and give children technological tools from an early age. Initially, the school started with programming classes and robotics. The children learn how to create electronic circuits and install sensors and other robotic devices. Now the programmes are expanding to 3D design, drone assembly, mobile-app creation and even video production for YouTube.

García’s vision encompasses more than just technology, though; Elemental’s motto is ‘To Prepare Our Children for the Jobs of the Future.’ And this involves instilling creativity, leadership skills and resilience. Using the car experiment mentioned above as an example, the students develop critical thinking: ‘They start building the car, we give them the materials, and we give them a balloon,’ García says. ‘So they blow the balloon but it’s not stable, or it doesn’t go as far as they want. Only with trial and error can they solve the problem.’

Launching this month on 9 April is one of Elemental’s new programmes: STEAM, which stands for Sciences, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics. It’s an inclusive, months-long multidisciplinary course that dabbles in all these areas, in addition to entrepreneurship and financial education. Children start with programming, then 3D design. They start mapping different car parts before 3D printing them. They then build electronic circuits to make that car move. Then comes the applied-sciences innovation module, in which the students are confronted with a problem that they have to solve. As García puts it: ‘It’s a learning process that teaches them that they won’t get it right the first time. They develop resilience. They learn to not get frustrated and to learn how to fail.’

With this project, García is empowering a new generation to better equip themselves for the future so they can become actors of social change. ‘Most of these social problems can be solved with technology,’ García believes. ‘And the solution can come from the citizens.’ Her social responsibility initiative ‘Digital Heroes’ is a technological contest that Elemental organises in partnership with the municipalities of La Paz and El Alto, in which children and teens are asked to identify a problem in their communities and solve it by creating mobile applications. This also involves developing a business model to generate money for the apps to be sustainable.

‘Most social problems can be solved with technology. And the solution can come from the citizens.’

—Daniella García Moreno

Elemental and García’s successes are an encouragement to move forward and reach more people. Soon, a new Elemental location will open in Santa Cruz and, if García has her way, in other Latin American countries. The school is also targeting adults by offering courses on how to use Facebook for marketing and how to sell products online. Technology and sciences are not and should not be restricted to a small (geeky) fringe of the population; it’s a part of our everyday lives and deserving of more consideration and investment. But there’s also more work to do inside the school: García laments that only 10% of the 120 students enrolled in Elemental are girls, but she is working on changing that, setting an example for a new generation.

For more information:

Address: 6 de Agosto #2549, La Paz

Tel.: +591 71566132, +591 72254077

http://www.elementalschool.com/

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

Sebastian Quiroga’s gourmet meat-free mission

On the corner of Calles Potosí and Colón in the bustling, chaotic centre of La Paz, tucked between two chicken restaurants, almost out of sight, stands the gourmet vegan boîte Ali Pacha and newly opened café-bar Umawi. Here I find head chef and founder Sebastian Quiroga. As I sit down, he presents me with an espresso shot placed on a floppy-disk coaster. As everything else here, the coffee is 100% Bolivian; the taste and the presentation reflect the overall quality of the experience.

In 2012, Quiroga, born in La Paz, travelled to London to study at Le Cordon Bleu culinary school, where he received classical training in French cuisine. He then joined the team at Copenhagen’s famed Restaurant Relae for a six-month internship. There, he was introduced to a new idea of cuisine, one which doesn’t necessarily involve meat as the centerpiece of the dish. He then returned to Bolivia with a freshly formed idea of starting his own business. One and a half years later, Ali Pacha was born. Since then, the restaurant has received international recognition in three different categories at the 2017 World Luxury Restaurant Awards: South American Cuisine Global Winner, Best Cocktail Menu Continent Winner and Gourmet Vegan Cuisine Continent Winner.

Quiroga’s concept is simple: give a flavourful, 100% Bolivian gourmet experience, without using any animal products. And this vision doesn’t stop with the food and drinks; it also involves Ali Pacha’s service, decor and design. Most of the objects in both the restaurant and the café-bar are secondhand, recycled items purchased locally that also carry cultural significance. Pointing to the electrical cables that decorate Ali Pacha’s ceiling, Quiroga explains that it’s all meant to reference the chaos of La Paz outside the door – albeit in a more organised way – and that the essence of the place is truly Bolivian in nature.

Quiroga’s concept is simple: give a flavourful, 100% Bolivian gourmet experience, without using any animal products.

For Quiroga, the restaurant and café ‘showcase what the country has to offer, which also happens to be vegan.’ Everything is plant-based, and everything comes from Bolivia, from the quinoa and potatoes native to the west of the country to exotic and less-known tropical fruits found in Bolivia’s eastern jungles. Quiroga brings the entirety of the country together on the plate, carefully and creatively combining ingredients that would never have met elsewhere.

Ali Pacha means ‘Universe of Plants’ in Aymara. Veganism came as a surprise to Quiroga, something that he learned about during his time abroad and after watching the 2005 documentary Earthlings, which powerfully and brutally depicts the realities of the meat industry. ‘I come from a family of meat-lovers. I used to go fishing and hunting when I was younger,’ Quiroga recalls, still slightly surprised by how much he has changed. Alongside a growing vegan/vegetarian offering in La Paz, Quiroga wants to provide a high-quality cuisine in which flavour comes first. ‘The priority is not necessarily to be healthy; it’s to cook good food,’ he says. ‘Sometimes people walk in and they don’t know that there is no meat, so I need to convince them to stay,’ he adds. ‘When that happened [when we first opened], I used to tell these people, “If you don’t like it, you won’t have to pay.” But people have always paid.’ The food, it seems, speaks for itself.

‘The priority is not necessarily to be healthy; it’s to cook good food.’

—Sebastian Quiroga

Opening the restaurant in the centre of La Paz wasn’t an obvious or easy choice. In an area where fast-food options proliferate and buildings are falling apart, Quiroga saw potential and an opportunity to revitalise the old centre. Two years after opening, Quiroga’s bet is paying off, with the addition of the new café-bar Umawi, which in Aymara means ‘Let’s drink!’ Umawi offers a selection of the best Bolivian coffees and liquors, accompanied with a selection of sandwiches and snacks. Quiroga wants to see these ingredients shine in signature cocktails and by using modern coffee-making techniques. Undoubtedly, when visiting Ali Pacha and Umawi, Quiroga’s passion for gastronomy and his country stands out and can be appreciated in the care and consideration put into each detail.

For more information:

Ali Pacha and Umawi Coffee and Bar: Calle Colón #1306, La Paz

Tel.: +591 2202366

Download

Download