According to the 2017 Global Innovation Index, Bolivia ranks 106th (Switzerland ranks 1st), making it the last South American country to appear on the list. This index, elaborated jointly by Cornell University, the INSEAD Business School and the World Intellectual Property Organisation, looks at 130 world economies taking into account a dozen parameters such as government expenditures in education and research-and-development investment. Bolivia ranking low on the list can be viewed as demoralising, but it also means that there is only progress to be made. One need only to look around to see the country’s potential.

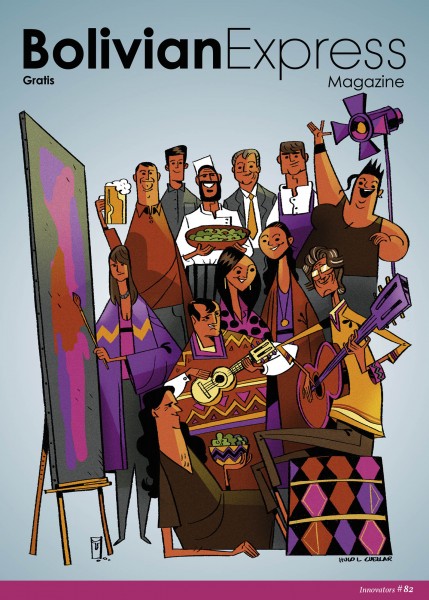

I mentioned in last month’s editorial how a mentality of mediocrity can hold back both people and nations. A painful history of colonisation, dictatorship and inequality has impeded growth and, until now, hindered innovation. But this is changing. In this issue of Bolivian Express, we have selected 12 innovators, each with an idea and a vision, each thriving to create a new future for Bolivia. Twelve people, all very different, but who have in common the same underlying, indeniable and unwavering passion – a zeal for their work fueled by a profound love for their country.

Included are some that have adopted and embraced Bolivia. Based in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Guido Mühr brought German brewing techniques to Bolivia and created Prost, a new but already very popular beer. From Slovenia, Ejti Stih watched her home country splinter during the Yugoslav Wars and now paints politically-charged art. Stih’s message is brutal – her last series graphically depicts abortion – but only because she wants to be a voice for social change. She is not alone in this: Film director Denisse Arancibia delivers in her movies light-hearted fun with an added layer of provocative social commentary.

Bolivian products are starting to shine; the country has much to offer in diversity and quality. Sebastian Quiroga, head chef of vegan gourmet restaurant Ali Pacha, showcases this in his dishes and the products he uses. And another underappreciated resource that is just beginning to stand out is the coffee from Los Yungas. Mauricio Diez de Medina, coffee enthusiast, is setting out to transform the Bolivian coffee industry. Paul ‘Pituko’ Jove, another entrepreneur we chose to highlight this month, is by day the owner of the vegetarian restaurant Namaste and by night a DJ working on consolidating the electronic music scene in La Paz.

This month, we look at the innovators, entrepreneurs and influencers who are taking Bolivia and Latin America to the next level. There is fashion designer Ericka Suárez Weise and leather-goods creator Bernardo Bonilla, two upcoming talents in Bolivia’s creative scene. But ultimately, education is the key to encourage innovation and improve social conditions. Daniella García, CEO of the Elemental technological school, understands this and wants to empower Bolivian children to embrace and learn how to use technology.

These changes wouldn’t be possible without the influence and impact of Bolivian legends Ernesto Cavour and Matilde Casazola, artists who keep new generations motivated with melodies and words that still resonate today. Here we present you 12 profiles, 12 passions and 12 ways to be inspired.

Photo: Ana Diaz

Inside the fertile mind of the Bolivian musician, inventor, author and investigator

Once described as ‘the best in the universe’ when it comes to Bolivia’s national-heritage instrument, Ernesto Cavour can be found playing his beloved charango and other musical creations at the Teatro del Charango in La Paz every Saturday night. I catch up with Cavour to discuss his colourful life, in which he’s succeeded in making his creative visions a beautiful musical reality.

Completely self-taught as a musician, Cavour cites ‘a strong and profound love and passion’ as one of his biggest motivations since he first picked up a charango as a boy in 1950s La Paz. His mother, who raised Cavour alone, didn’t want him to be a musician, ‘but I resisted and made promises,’ says Cavour.

This wasn’t his only professional obstacle, however. ‘I was completely timid as a young person,’ explains Cavour. ‘I was scared to get up to the microphone and play… I found it impossible to play in public, and when I did manage to, I’d start to stutter. My voice, my fingers... nothing responded, to the point that I would play almost paralysed.’

But with a successful career as a soloist as well as part of renowned groups such as Los Jairas and El Trío Dominguez, Favre, Cavour, how did he overcome this?

‘One day, a man who came to my house with my neighbour told me, “You play instruments well, why don’t you join the theatre?” And I said, “No, I’m too scared.” And he told me that I needed to socialise with music and art, that I couldn’t just play on my own. And that’s how I ended up joining the national ballet,’ says Cavour.

In this way, the future charango maestro was able to travel all over Bolivia performing for miners and workers, while at the same time experiencing the country’s timeless magic and beauty. ‘The time hadn’t passed, it had stayed in the same moment,’ Cavour reminisces, as he takes me back to the 1960s. ‘Bolivia was paradise in those days.’

‘There wasn’t anyone there to bother me or tell me “You can’t do that!” and there were already a lot of guitar necks. So I made the most of it and that’s how the guitarra muyu-muyu first came about.’

—Ernesto Cavour

It was also during these travels that he started collecting musical instruments of all kinds, a habit that would later influence his work as a museum curator, an investigator and an inventor of musical instruments. ‘I started to collect instruments because they were very cheap, around 15 bolivianos each,’ says Cavour, who appreciated the beauty and the natural, varied sounds of these instruments which were made in the countryside. ‘I saw vihuelas, guitars, charangos, and so many other instruments with different names,’ he continues. ‘There were flutes of all sizes, of every colour, and every material. There were incredible things that just aren’t around anymore.’

In 1962, Cavour founded the first incarnation of the Museo de Instrumentos Musicales de Bolivia in his house. The museum now resides in a beautiful and spacious colonial house on Calle Jaén in La Paz, where it is home to more than 2,500 musical instruments, including pre-Hispanic pieces. The building also houses the Teatro del Charango, an art gallery, a library, and a workshop, where music lessons are also offered.

During a brief tour of Europe in the late 1960s and early 1970s with Los Jairas and Alfredo Dominguez – pioneers of the criollo style – Cavour had the opportunity to develop his skills as an inventor of musical instruments. Inspired by what he observed in the workshops of the master luthier Isaac Rivas, Cavour was further encouraged to invent when he started writing his first music-theory books. ‘I started, for example, writing methods that would allow people to play the charango more easily… because there were no methods available then,’ he says. His first book, El ABC del Charango, was published in 1962, and ‘it was with these books that I started to create.’

In a large abandoned factory in Switzerland, Cavour experimented with instrument design. ‘There were machines there, at my disposition,’ explains Cavour. ‘There wasn’t anyone there to bother me or tell me, “You can’t do that!”, and there were already a lot of guitar necks. So I made the most of it and that’s how the guitarra muyu-muyu first came about. I then finished it when I returned to Bolivia.’ One of Cavour’s most successful musical inventions, the guitarra muyu-muyu has been popularised by the technical skill of colleague Franz Valverde who, along with esteemed quenista Rolando Encinas, accompanies Cavour each Saturday night at the Teatro del Charango concerts.

However, it is the two-row chromatic zampoña that Cavour is most proud of creating. ‘I searched around and figured out how to get all the tones in two rows,’ says Cavour. ‘Of course, it made things very simple. I played it [he hums the flute intro melody from his 1975 carnavalito classic ‘Leño Verde’] at Carnaval and it became famous… It was the departure for the zampoña to be used to make all kinds of rhythms.’

When I ask Cavour about the essence of his music, he is quick to point out that he doesn’t like to sing about women much, as there are so many degrading songs ‘about how [other artists] want to kiss them, their necks… bending them over… it insults women. What moves me more are customs, the earth and its foods,’ says Cavour, who laments that traditional Bolivian music has ‘stagnated’ in general, despite enduring in certain rural areas and with some contemporary musicians. ‘The way the world is advancing… [people] don’t want a huaynito,’ he says, referring to globalisation, consumerism and modern communication’s influence on popular tastes.

Despite this, Cavour has continually produced a lush banquet from the fruits of his passionate lifelong labours. I ask him what he hopes will happen with all this work in the future. ‘The museum still isn’t finished yet. I hope that in a year the museum is done. I have a few very important rooms in mind. It will enlighten the world about things that have happened, things that have been lost. Many tourists come here [to learn],’ says Cavour.

‘What moves me are customs, the earth and its foods.’

—Ernesto Cavour

One room Cavour has in mind will be dedicated to the natural origins of musical instruments. ‘Some things were created to be played as musical instruments,’ marvels Cavour, referring to any number of the naturally-formed instruments displayed in the museum. ‘I’m also working on a book [on musical instruments from around the globe] that will be important at world level. That’s what’s taking up my time.’

For more information:

The Teatro del Charango is located in the Museo de Instrumentos Musicales

Address: Calle Jaen #711, La Paz

Tel.: +591 22408177

Download

Download