According to the 2017 Global Innovation Index, Bolivia ranks 106th (Switzerland ranks 1st), making it the last South American country to appear on the list. This index, elaborated jointly by Cornell University, the INSEAD Business School and the World Intellectual Property Organisation, looks at 130 world economies taking into account a dozen parameters such as government expenditures in education and research-and-development investment. Bolivia ranking low on the list can be viewed as demoralising, but it also means that there is only progress to be made. One need only to look around to see the country’s potential.

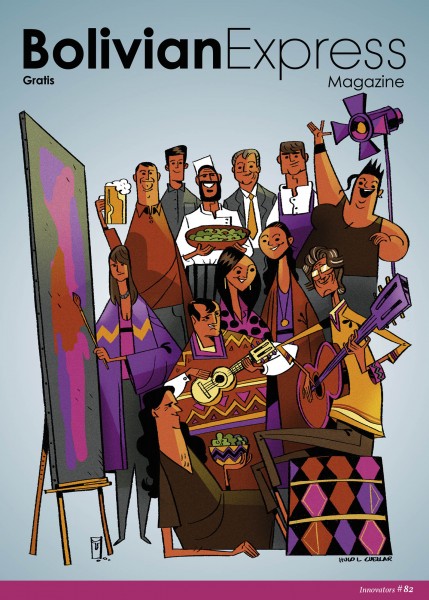

I mentioned in last month’s editorial how a mentality of mediocrity can hold back both people and nations. A painful history of colonisation, dictatorship and inequality has impeded growth and, until now, hindered innovation. But this is changing. In this issue of Bolivian Express, we have selected 12 innovators, each with an idea and a vision, each thriving to create a new future for Bolivia. Twelve people, all very different, but who have in common the same underlying, indeniable and unwavering passion – a zeal for their work fueled by a profound love for their country.

Included are some that have adopted and embraced Bolivia. Based in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Guido Mühr brought German brewing techniques to Bolivia and created Prost, a new but already very popular beer. From Slovenia, Ejti Stih watched her home country splinter during the Yugoslav Wars and now paints politically-charged art. Stih’s message is brutal – her last series graphically depicts abortion – but only because she wants to be a voice for social change. She is not alone in this: Film director Denisse Arancibia delivers in her movies light-hearted fun with an added layer of provocative social commentary.

Bolivian products are starting to shine; the country has much to offer in diversity and quality. Sebastian Quiroga, head chef of vegan gourmet restaurant Ali Pacha, showcases this in his dishes and the products he uses. And another underappreciated resource that is just beginning to stand out is the coffee from Los Yungas. Mauricio Diez de Medina, coffee enthusiast, is setting out to transform the Bolivian coffee industry. Paul ‘Pituko’ Jove, another entrepreneur we chose to highlight this month, is by day the owner of the vegetarian restaurant Namaste and by night a DJ working on consolidating the electronic music scene in La Paz.

This month, we look at the innovators, entrepreneurs and influencers who are taking Bolivia and Latin America to the next level. There is fashion designer Ericka Suárez Weise and leather-goods creator Bernardo Bonilla, two upcoming talents in Bolivia’s creative scene. But ultimately, education is the key to encourage innovation and improve social conditions. Daniella García, CEO of the Elemental technological school, understands this and wants to empower Bolivian children to embrace and learn how to use technology.

These changes wouldn’t be possible without the influence and impact of Bolivian legends Ernesto Cavour and Matilde Casazola, artists who keep new generations motivated with melodies and words that still resonate today. Here we present you 12 profiles, 12 passions and 12 ways to be inspired.

Photo: Courtesy of Prost

Brewmaster Guido Mühr’s motto: ‘Cerveza alemana hecha en Bolivia’

Formerly dominated by domestic brew behemoths Paceña and Huari, Bolivia is experiencing a beer renaissance as of late, with small craft cervecerías such as Saya, Niebla and Corsa springing up all over the landscape, from Sucre and Cochabamba to La Paz and Santa Cruz de la Sierra. And now there’s another contender in the ring, one that’s producing suds reminiscent of his homeland. Prost, the brand name of master beer-maker Guido Mühr’s Sabores Bolivianos Alemanes company has, in two and a half years, catapulted itself into the Bolivian beer market with distribution to most of the country’s major cities and their outlying areas. It’s a labour of love for Mühr, 52, who studied beer-making in Munich and worked at the Holsten brewery in Hamburg before he responded to a mysterious ad in a local trade publication in 1992 that would dramatically alter the trajectory of his life. ‘I read about an offer for a new brewing plant in South America,’ Mühr says from his office at the Prost brewery on the outskirts of Santa Cruz. ‘It said only ‘South America.’ I thought it was in Buenos Aires or Rio de Janeiro, but it was indeed in Santa Cruz de la Sierra.’

Shortly thereafter, the then-27-year-old Mühr was on his way to Bolivia, a country he knew little about on a continent he had never visited. ‘I knew no Spanish,’ he recounts. And there was 'no Internet, and it was only phone calls and letters – written letters! It was quite different. It was very tropical… very, very different from Europe or from Germany. My first impression was “Oh my goodness!”’

But Mühr thrived in the tropical environment, working for Paceña for seven years before it was acquired by the Argentinian beer company Quilmes. In turn, Quilmes was purchased by the international beer conglomerate AmBev, which then offered Mühr the opportunity to manage two breweries and a Pepsi bottling plant in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 2008. So Mühr, who by this time had started a family with his Bolivian wife, packed his bags and headed east.

It’s a labour of love for Mühr, who studied beer-making in Munich before he responded to a mysterious ad in a local trade publication that would dramatically alter the trajectory of his life.

But Mühr was becoming dissatisfied with the corporate life. ‘Every brewmaster in this life thinks about having his own brewery, making his own beer,’ Mühr says. ‘If you, for nearly 20 years, have to think only in terms of cost reductions and how to make the product cheaper every time, then you start to dream about doing your own business.’

And so Mühr filled his last Quilmes keg in 2012 and laid low for a year, formulating a business plan for his next endeavour. With an eye on Santa Cruz’s explosive population growth, cheap labor and little-penetrated beer market, Mühr and his family returned in 2013. He immediately made contact with investors from local pubs and restaurants. Brewery construction started in 2014, in a near-deserted industrial part far north of the city, under less-than-ideal conditions. ‘We weren’t connected to electric energy until March 2015, so we nearly built the factory without it,’ Mühr says, wincing, as he stands outside his factory in the intense tropical heat. ‘We started brewing in June 2015 – three months later.’

Prost’s initial production run was only 1,000 litres per month, but in the last two and a half years it’s now producing 35,000 to 40,000 litres monthly – still not enough for the company to break even financially. ‘But that’s OK,’ Mühr says. ‘We are increasing every year from between 25 and 50%. Fortunately, I have long-term-looking partners and not short-term, cash-bar-searching partners.’ And there’s a lot of room to grow: The brewery’s maximum yearly capacity is 8 million litres. ‘But if we reach that number,’ Mühr says, laughing, ‘I will be drinking caipirinhas en la playa.’

The Prost brand boasts five lines currently in production – its signature premium lager (just about a perfect beer for the infernal cruceño climate), a Weiss (wheat), a dunkel, a quinoa beer and a winter and a summer ale. Mühr plans to keep the distribution strictly in-country, with the exception of the quinoa beer, which he plans on making available in Peru. He’s also busy brewing a new line, an IPA, which will be available later this year.

‘Every brewmaster in this life thinks about having his own brewery, about making his own beer.’

—Guido Mühr

Prost is a small business, with only 12 full-time employees staff, and the distribution and sales are outsourced to trusted partners, allowing Mühr to concentrate on what he really loves: brewing good beer. ‘Every brewmaster at least dreams of having his own brewery, big or small, but to do this﹣’ he says, gesturing at his brewery, ‘that’s always been my dream.’

But even with this achievement, Mühr, who is tall and gangly with dark black hair and a face faintly lined from living under the tropical sun for years, is also thinking ahead. ‘I wanted to [start the Prost brewery], and I want to [run it] for the next 10, 15 years,’ he says. And he’s also looking beyond Bolivia, into other markets – but he’s keeping his lips sealed about that plan, at least for now. He does reveal one thing, though, as he stands proudly in front of his brewery: ‘This should only be one of several projects,’ he says, smiling.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

Handcrafted Leather Goods and Travel Accessories

It is 25-year-old commercial engineer Bernardo Bonilla’s dream that his enterprise, aptly named Vagabond, translates the experiences he’s had during his travels abroad. When he finished his studies at the Universidad Católica Boliviana back in 2014, Bonilla embarked on a trip to France as part of an employment programme through Campus France, promoted by the French embassy in Bolivia, an eight-month trip which opened his mind to experiences and ways of life that would eventually inspire him to found his business, a shop which sells leather goods to men with all the promise of freedom and the thrill of carefree, nomadic wandering that the name suggests.

The business was conceived back in 2016 when the Bonilla family spotted a gap in the paceño market: there were so few stores which sold gifts for men that the typical go-to was to buy a nice shirt. And there are only so many times you can buy someone a shirt. So Bonilla, together with his mother and sister, sat down to brainstorm. It was clear from the onset that they would sell products for everyday use with a high level of functionality and a clean, minimalist design. Another key aspect of the company is that each product they create is 100% Bolivian, without being made from the conventional, traditionally Bolivian materials, deriving from llama or alpaca wool. And, although the leather market is relatively undeveloped here, the family’s ethos has always been to produce the highest quality product, but at an affordable price.

The well-travelled Bonilla family remembers their first product, a travel document holder which itself becomes a memento, according to Bonilla: ‘each wrinkle in the leather gives the item more personality and, with the passing of time, as it gets older, more aged, and wrinklier, it becomes a special, collectable item that carries with it the memories of the places it’s been to.’

Vagabond is leather-goods shop that evokes the freedom and the thrill of a carefree, nomadic life.

Now, their products range from wallets and purses to tablecloths. They also create personalised products according to customers’ specific requests. This was the case with Mauricio Lopez, head chef of La Paz’s prestigious restaurant Gustu, who asked for a case in which to keep his chef’s knives, a request to which he later added cooking-gloves among several other items. Businesses such as Huawei, Hotel Rennova, Banco Fie, Restaurante Margarita, Cervecería Boliviana Nacional, and Samsung, have similarly followed suit.

There are only so many times you can buy someone a shirt.

Vagabond is not only selling products, but is also making a social change. The business had a hand in improving the quality of life of such people as Alberto Maidana who’s worked his whole life as a tailor. He’d never worked with leather before, but Vagabond trained him to create leather goods for the Bonilla business.

Among the family business’ current projects, they’ve launched a sister-company of women’s clothing called ‘Slavic.’ In addition to opening more branches in La Paz, they’d like to develop their brand’s capacity to improve people’s quality of life, and so they’re currently looking for ways in which the income that Vagabond products generate can go towards a good cause.

For more information

Address: Gabriel Rene Moreno #1307, Edif. Mizutan

Tel.: +591 73015516

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

Laboratorios Crespal S.A. A family business goes big

Back in the 1950s, La Paz was a small city where practically everyone knew each other. Nearly all the country's decisions – political, economic and social – took place in what is known today as the Club de La Paz, located on Avenida Camacho. There, the Bolivian elite of that time would meet, spend time together and hash out the country’s future. Raúl Crespo Palza, one of the few Bolivian pharmacists of that era, opened a pharmacy nearby and named it El Indio. Located on Calle Colón near the Club de La Paz, it would later be renamed Farmacia Santa Cruz in honour of Crespo’s cruceña wife, Neysa Vasquez.

For 15 years, the pharmacy, which also became an important meeting point, witnessed the country’s political and economic crises: the 1952 National Revolution that would give rise to the first MNR government, followed by military governments, all of which would lead to the fall of the national economy in the 1980s. This is when the UDP political alliance, headed by Hernán Siles Suazo, took the reins of the Republic of Bolivia. Hyperinflation followed, and with an absence of foreign currency and a shortage of medicine, Farmacia Santa Cruz couldn’t provide medical supplies to the citizenry. But the crisis provided an opportunity, and Crespo opened a laboratory to manufacture his own pharmaceuticals. His son, Raúl Crespo Vásquez, tells me that his father started out by grinding antibiotics and mixing syrups by hand in the absence of the necessary equipment.

Learning from his father’s trevails, Crespo Jr. studied agronomic engineering and originally found work in the agricultural industry. He spent his days in the countryside, where he bred animals and founded a small jam factory. For legal reasons, and to be able to commercialise his products, he needed another factory in La Paz. His family owned property in the San Pedro neighbourhood on Calle Nicolás Acosta. He located his new factory there, and now it’s the location of Laboratorios Crespal S.A.

Crisis provided an opportunity, and Raúl Crespo Palza opened a laboratory to manufacture his own pharmaceuticals.

It took six months for Crespo Jr. to become completely involved in the pharmaceutical laboratory. Farmacia Santa Cruz, then still led by Crespo Sr., made sure the family was fed and helped finance the new laboratory. Eventually, Crespo Jr. took over its administration and management. Laboratorios Crespal’s initial production run included Sorojchi altitude-sickness pills, which most visitors to the city will be familiar with, and the Carmelinda cosmetic-product line. Through the years, the company has kept growing with new products regularly launched.

Laboratorios Crespal’s Sorojchi-pill formulation, which combats the symptoms of males de altura, dates from the 1960s and is the product of a rather atypical partnership with the then US Consulate. The US Peace Corps, an American volunteer program providing social work in Bolivia and elsewhere around the world, requested that Crespal Sr. formulate a remedy for altitude sickness, which was adversely affecting the organisation’s Bolivian staff. Crespo Sr., who died in 1996, began experimenting and conducted clinical studies until he formulated the product we know today.

The Sorojchi pill dates from the 1960s and is the product of a rather atypical partnership with the then US Consulate.

Strong demand for the Sorojchi pills was immediate, especially from tourists, and pharmacies in other high-altitude tourist destinations soon began to order the product. Exportation to Peru began after a young man named Armando, from Puno, started bulk-purchasing the medicine to sell in Peru in order to finance his university studies. Crespo Jr. realised that there was demand in the neighbouring country and started to distribute them to Cuzco, where they were particularly popular with tourists who hiked the Inca Trail. Laboratorios Crespal now has a branch in Peru, and plans to export its products to Ecuador and Mexico.

Laboratorios Crespal’s Sorojchi pills are also becoming well-known outside of South America. In 2016, the company received a call from the government of Tibet, inquiring about the distribution of the altitude-sickness pills in its capital, Lhasa. There have even been two heads of the Catholic Church who have taken the Sorojchi pill: Pope John Paul II, when he visited La Paz in 1988, and Pope Francis in 2015. Sorojchi pills are advertised as the most effective product to alleviate the symptoms of altitude sickness for tourists in extremely high-altitude cities such as La Paz and Cuzco.

Laboratorios Crespal, all the while, keeps growing. In 2014, it opened at modern pharmaceutical plant in El Alto. For the past 30 years, Crespo Jr. has been managing it, and it is listed on the Bolivian Stock Exchange. But all these changes do not mean that the company ceases to be deeply rooted in paceño traditionalism with a family legacy that embodies everything that is Bolivian.

Download

Download