According to the 2017 Global Innovation Index, Bolivia ranks 106th (Switzerland ranks 1st), making it the last South American country to appear on the list. This index, elaborated jointly by Cornell University, the INSEAD Business School and the World Intellectual Property Organisation, looks at 130 world economies taking into account a dozen parameters such as government expenditures in education and research-and-development investment. Bolivia ranking low on the list can be viewed as demoralising, but it also means that there is only progress to be made. One need only to look around to see the country’s potential.

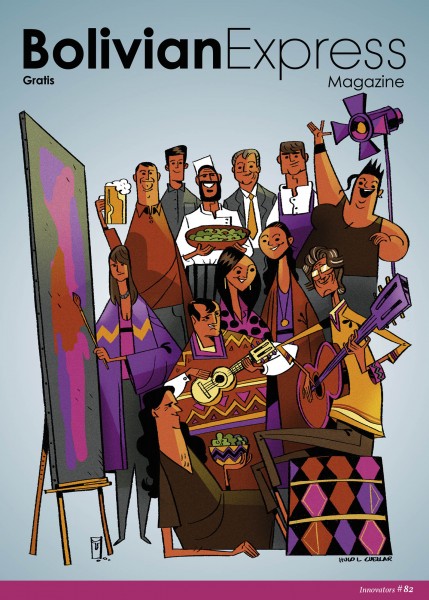

I mentioned in last month’s editorial how a mentality of mediocrity can hold back both people and nations. A painful history of colonisation, dictatorship and inequality has impeded growth and, until now, hindered innovation. But this is changing. In this issue of Bolivian Express, we have selected 12 innovators, each with an idea and a vision, each thriving to create a new future for Bolivia. Twelve people, all very different, but who have in common the same underlying, indeniable and unwavering passion – a zeal for their work fueled by a profound love for their country.

Included are some that have adopted and embraced Bolivia. Based in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Guido Mühr brought German brewing techniques to Bolivia and created Prost, a new but already very popular beer. From Slovenia, Ejti Stih watched her home country splinter during the Yugoslav Wars and now paints politically-charged art. Stih’s message is brutal – her last series graphically depicts abortion – but only because she wants to be a voice for social change. She is not alone in this: Film director Denisse Arancibia delivers in her movies light-hearted fun with an added layer of provocative social commentary.

Bolivian products are starting to shine; the country has much to offer in diversity and quality. Sebastian Quiroga, head chef of vegan gourmet restaurant Ali Pacha, showcases this in his dishes and the products he uses. And another underappreciated resource that is just beginning to stand out is the coffee from Los Yungas. Mauricio Diez de Medina, coffee enthusiast, is setting out to transform the Bolivian coffee industry. Paul ‘Pituko’ Jove, another entrepreneur we chose to highlight this month, is by day the owner of the vegetarian restaurant Namaste and by night a DJ working on consolidating the electronic music scene in La Paz.

This month, we look at the innovators, entrepreneurs and influencers who are taking Bolivia and Latin America to the next level. There is fashion designer Ericka Suárez Weise and leather-goods creator Bernardo Bonilla, two upcoming talents in Bolivia’s creative scene. But ultimately, education is the key to encourage innovation and improve social conditions. Daniella García, CEO of the Elemental technological school, understands this and wants to empower Bolivian children to embrace and learn how to use technology.

These changes wouldn’t be possible without the influence and impact of Bolivian legends Ernesto Cavour and Matilde Casazola, artists who keep new generations motivated with melodies and words that still resonate today. Here we present you 12 profiles, 12 passions and 12 ways to be inspired.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

Talking coffee with Mauricio Diez de Medina, the owner of Roaster coffee shop

Over the past decade, the Bolivian coffee industry has transformed thanks to a dedicated group of influencers, one of whom is Mauricio Diez de Medina. From his time as a young man working in the financial industry, and now as an artisanal coffee roaster and owner of a high-quality coffee shop in the San Miguel neighbourhood of La Paz, Diez de Medina’s journey has been a caffeine-fuelled rollercoaster ride, starting in the jungle.

In 1999, a group of Colombian entrepreneurs asked Diez de Medina for financial support with their new project, artisanal coffee production. He agreed and travelled with them to the Bolivian jungle to visit some coffee plantations. ‘From the moment I witnessed the process, I fell in love,’ says Diez de Medina, his piercing blue eyes glinting with enthusiasm. He was struck by the beauty of the laborious production process and the dedication of the farming families, most of whom had never even tasted their own coffee and were underpaid by the major coffee companies.

Diez de Medina’s journey has been a caffeine-fuelled rollercoaster ride, starting in the jungle.

This experience ignited a passion and a drive in Diez de Medina. He brought with him a new resolve when he returned to La Paz: he would provide an alternative to the poor-quality coffee that was rife in Bolivia. He would spread the word that good coffee should not be solely for export, but for local consumption and enjoyment as well, and he would do all of this while respecting, supporting and cooperating with the coffee-farming families. Thus began his coffee-producing career. His company, Roaster, now sources and roasts coffee from various farms in the Yungas region of Bolivia, every bean selected with the highest standard of quality in mind.

‘But it only takes a matter of seconds for a barista to turn a high-quality coffee bean into a terrible coffee,’ Diez de Medina says, shaking his head. The Roaster team consider themselves pioneers of barismo de altura, but this was not a title easily won. When Roaster first opened its doors six years ago, the biggest challenge facing Diez de Medina and his team was consistent quality. If they wanted to spread the message that multinationals had deceived Latin Americans about the standards of quality they should expect in their coffee, then they had to deliver one perfect cup after another.

The road was long, but perhaps made more bearable by caffeine and a healthy dose of enthusiasm. When asked about his work-life balance, Diez de Medina simply smiles, his eyes lighting up as he explains that when you are truly passionate about something and are supported by like-minded people, work ceases to be work and becomes your life. He talks about hard times, such as the backlash from the industry when he decried its quality standards, but always with a confident smile. ‘We have achieved our social objective,’ he says, referring to the fact that artisanal coffee shops are now plentiful in La Paz and popping up all over Bolivia and Latin America in general. Through good practice, lobbying and barista coffee-culture courses, the Roaster team has been instrumental in redefining the standards of coffee produced and consumed within the continent.

It is refreshing to see that, in spite of an increase in competition in the market as well as being a purist at heart, Diez de Medina remains truly enamoured with the coffee industry. One of his dreams is to have a Bolivian win the World Barista Championship, and he excitedly tells me about his coffee laboratory, equipped with the latest technology and open to any barista that wants to train and practise for the championship. ‘It can be available for them 24 hours a day,’ Diez de Medina says.

Through good practice, lobbying and barista coffee-culture courses, the Roaster team has been instrumental in redefining the standards of coffee produced and consumed within the continent.

I comment light-heartedly on how lucky he is to have made his career out of something he loves. Diez de Medina fixes me with a steely-eyed stare: ‘Coffee has given me everything I have: a culture, a career. It has made me more human, it has allowed me to see the good and the bad of humanity, but most of all it has made me see how important it is to work around your passion.’ It is this belief, that humans should live by their passions, all the while respecting one another, that has created the business that Roaster is today. It is a great environment in which to work and socialise; it supports small coffee farmers and it’s a spokesperson for quality coffee in Bolivia. All in all, it is the realisation of Mauricio Diez de Medina’s dream.

For more information:

Address: San Miguel, Rene Moreno E 20, La Paz

Tel. +591 2147234

http://www.roasterboutique.com/

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

A tendentious exhibition from the cruceña artist looks at abortion

The red-tinged brick Santa Cruz Cathedral towers above the city’s central square, the Plaza Principal 24 de Septiembre. Beneath the oppressive sun, cruceños sit on park benches underneath palm-tree canopies, sipping cafés con leche as dusk slowly creeps over the city. Nearby, the sculpture garden of the Galería Manaza slowly fills with people as the hot, humid day gradually turns into night. Inside the gallery, blood-red and gold paint throbs on the studio’s walls. Sinister clergy and nuns are depicted hovering over piles of babies’ bodies. A young women gazes down at gallery goers with her face frozen in a rictus of immense sorrow. A blindfolded figure of Justice uses a long knife to slice at a bloody umbilical cord from which a newborn child swings like a pendulum. A devilish angel scoffs at a black plastic garbage bag ominously crammed full of… what? Does the viewer even want to know?

Welcome to Rojo y Oro, a new exhibition by the Slovenian-born artist, Ejti Stih. Born in communist Yugoslavia in 1957 and a resident of Santa Cruz since 1983, Stih explains how she conceived of her exhibition. A few years back, she says, ‘There was a case of a girl who was 11 years old, and she was raped by her stepfather. It was a public case, and her mother was on television, with a bag on her head [to hide her identity]. She was asking for the abortion. There were newspapers and the church and social workers and everybody was commenting on it on the television – and it was so terrible because nobody asked the girl what she thought.’ The court ruled that the girl had to carry her baby to term. A year later, the baby died. ‘It was a difficult case,’ Stih says. ‘I am also a mother, I also have a daughter, and I was deeply moved.’

In response to the media spectacle surrounding this case, Stih created Homenaje a la niña violada, a painting depicting a young girl, naked and vulnerable, surrounded by the violently abstracted figures of politicians, clergy and the public. The girl cowers at the bottom of the frame, trying to shield herself from the frothing masses. ‘This painting was hanging in our house for years,’ Stih says, ‘and these stories go on every day.’ Then, late last year, as lawmakers started to consider a new penal code that would allow abortion in a few special circumstances (which ultimately failed to pass in the Bolivian legislature), Stih decided to return to the subject.

‘Women sometimes have to [get an abortion] – there’s no other choice. And they will do it.’

—Ejti Stih

‘When I was thinking about making this exhibition,’ Stih says, ‘I remember that I was with two friends at a dinner and I said that I was thinking about this abortion series, and they said, “Don’t! Don’t!”’ Stih laughs. ‘I mean, I don’t care! [Abortion is] a question of social health. Women sometimes have to do it – there’s no other choice. And they will do it.’

It’s a difficult exhibition to view, full of sorrow and the suffering of women who must deal with unwanted pregnancy or the danger of a clandestine abortion – and the indifference of the church and the state to this suffering. ‘In poor countries, poor people, poor women suffer most,’ Stih says. ‘There’s a lot of suffering in vain.’ As the exhibition’s title suggests, the paintings are primarily in a deep, thick red and a shimmering gold. ‘This gold has to do with ancient, old, religious paintings,’ Stih says. ‘Gold is a colour that doesn’t define space, because when it’s gold it might be far away or near – it represents eternity.’

Stih studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, Slovenia. After graduating from the academy, she followed some Bolivian friends of Croatian descent to Bolivia, where she’s lived ever since. She’s exhibited her work throughout Europe, Central and South America, and the United States. Although she primarily focuses now on painting, she’s also created lithography and ceramic pieces. In contrast to her current exhibition, which can be gloomy, Stih is quick to laugh when speaking about herself and her artwork. She glad-hands admirers warmly; several times when speaking about her work in the gallery she is interrupted by women, some in tears, who tell her how affecting her artwork is. Stih is quick to chat them, and to offer a hug.

Steven and Kenyon Hall, two Bolivian-Americans visiting from Washington, DC, said they were moved by the exhibition. ‘If anything, it definitely makes us question ourselves and what we think, and hopefully people come in can see and think for themselves,’ Kenyon says. ‘Especially, I hate to say it, men – they come in here they see and think about how this could be their mum or sister.’ ‘When we first walked in, I think the first emotion that I felt was, I felt a little uncomfortable, and I think that’s great,’ Steven said. ‘It sparks conversation.’

‘In poor countries, poor women suffer most. There’s a lot of suffering in vain.’

—Ejti Stih

But Stih’s oeuvre isn’t all ponderous and weighty. Some of her past paintings are quite light. Her Nuevas Evos series, created back in the early days of Bolivian President Evo Morales’s first term, is a lighthearted look at the politician in which he’s depicted in many different traditional costumes from around the country. But even in these whimsical-looking pieces, there’s a deeper political message. ‘When Evo started to be the president, it was very difficult,’ Stih says. ‘It was a big confrontation between this Media Luna, the eastern part of Bolivia, and the rest of the country. It was politically very unstable. So I was thinking that I came so many kilometres – thousands of kilometres – away from Europe, away from Yugoslavia. I came so far and now this situation is the same because it was the war in Yugoslavia,’ in which the country splintered, something that was being threatened by the media luna in Bolivia in 2008. ‘Everything happened because the country split. So I said, “It can’t be! It can’t happen! This can’t happen to me again!”’ She created the Nuevas Evos series to humanise the new president. ‘I found it so nice, nice to the people, a nice present,’ she says. ‘That’s why I made the series.’

The power and pain apparent in Rojo y Oro, though, don’t make for a nice present, something that Stih acknowledges. ‘Who can have this in their house? Look at this painting! It’s impossible!’ she says, laughing. ‘I always make a joke. I create [other] paintings that combine with the sofa. Paintings that combine with the sofa have to have the proper colour for the living room, and the theme shouldn’t be as tough as this [to sell].’ Stih gestures at the morose paintings on the gallery’s walls. ‘So this will stay in my depository, and the others will help me live,’ she says. ‘That’s how I survive.’

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

A young designer is finding success in the country, and on the Hollywood red carpet

In the Equipetrol district of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, nestled amongst apartment towers and chic restaurants and cafés, Weise Atelier sits surrounded by adobe walls on a quiet side street. No sign indicates the presence of one of Bolivia’s premier fashion lines in the sprawling, steamy capital of the Santa Cruz department, but after entering through the iron gate and into the refreshingly cool interior, a visitor is greeted by a small woman in a crisp white shirt and dark slacks, ready to work and to chat, with a welcoming smile on her face and an infectious laugh.

Ericka Suárez Weise, 32, is the head of her eponymous ‘prêt-à-couture’ clothing line and the scion of a notable cruceña fashion design family. Her grandmother is a seamstress who fabricated clothes for a circle of traditional families in Santa Cruz when the metropolis was still only a village surrounded by jungle, and her mother, also named Ericka, is a designer who introduced modern women's fashion to the city in the early 1980s. ‘I grew up in the atelier,’ Suárez Weise says, ‘under the table actually.’ After studying fashion and textile design at University of Palermo in Buenos Aires in the early 2000s and living and working in the Argentine capital for a few years, she moved back to Santa Cruz in 2010, starting her own line in June 2011 in her mother's studio.

‘I grew up in the atelier, under the table actually.’

—Ericka Suárez Weise

‘When I came back [to Santa Cruz], there were no young Bolivian designers’ brands,’ Suárez Weise says. ‘It was just haute-couture designers, and the only other option was to buy Argentinian or Brazilian clothes. There were no young people making their own brands or fashion lines.’ Working out of her mother's atelier, she quickly designed her first collection, which was an immediate success. In 2012, she was named Designer of the Year by Bolivia Moda, the country’s foremost fashion-industry show.

Recently, Suárez Weise moved into a new atelier. ‘I was working in the same building as my mother and grandmother for eight years,’ she says. ‘I decided to move because I needed a bit more space. And actually, I needed this young spirit [of the new atelier] for my customers.’ The two-story building where she now works has dark wood floors and a small showroom in front with mannequins clothed in her latest creations. Her upstairs office features a small, organised desk. Bookshelves are filled with fashion and art books, and her personal studio downstairs has dozens of illustrations and photographs pinned to the wall and scattered about the work surface. In two outbuildings, her staff work on her latest creations, busily sewing, cutting and fabricating the newest Weise creations.

Suárez Weise is staking a middle ground between haute couture and prêt-à-porter. Her brand is a ‘middle moment,’ she says, ‘because it’s an accessible couture for people who cannot afford a US$100,000 piece, a Chanel. I have my “prêt-à-couture” brand, which works with the same artisanal ways of making couture, but in an accessible product.’ Her price point – US$200 to US$2,000 per creation, depending on materials – is certainly out of financial reach of the average Bolivian woman, but it’s accessible, even economical, to the cruceña high society that covets her designs. And even in La Paz, with its vastly different climate and fashion aesthetic, her line is making inroads. ‘The indigenous high society is starting to buy couture,’ Suárez says, ‘starting to feel comfortable going to a designer and asking for a wedding dress or a custom design.’

But now Suárez Weise is gaining recognition far beyond the narrow confines of the Bolivian fashion world – in fact, Hollywood has been taking notice. For the last two years at the Screen Actors Guild Awards, which is part of the seasonal run-up to the Oscars, Orange Is the New Black star Selenis Leyva sported dresses by Suárez Weise. In 2017, Leyva wore an elegant black gown with a ruffled train on the red carpet, and earlier this year the actress wore another Suárez Weise creation, one from her 2018 ‘Habitat’ collection, which was inspired by the orchid flower.

Suárez Weise’s collaboration with Leyva was serendipitous. ‘It’s a story of a friend of a friend of a friend. A friend introduced me to [Leyva's] stylist… And he looked at my work and he said, “I want to work with your brand.” I was like, “Oh my God!”’ she says, breaking into a laugh.

With Hollywood's spotlight shining on her brand from afar, Suárez Weise now finds herself in the enviable position of being able to extend her reach into other even larger markets. In New York City, she’ll soon be represented by a collective of emerging designers, and stylists in Los Angeles have expressed interest in her creations for their actress clients. ‘I work long distance now,’ Suárez Weise says. ‘I have stylists there that I work with who can do the alterations.’

But she’s not resting on her laurels, far from it. Besides influences as disparate as Dutch designer Iris van Herpen, who utilises 3D printing in her creations with strong nods to nature and fantasy, and stalwarts Chanel and Dior, Suárez Weise also looks close to home to guide her artistry. In 2016, inspired by a visit to Bolivia's Salar de Uyuni, Suárez Weise released her ‘Salt & Sky’ fall/winter collection. With lace that mimics the crystalline structure of the salt flats, gradual colour variations that symbolises the rising of the sun and feminine silhouettes under gossamer capes slightly reminiscent of cholita shawls, the collection exemplified an ultra-modern interpretation of one of Bolivia’s signature natural beauties. And last year, her fall/winter collection was heavily inspired by the late cruceño painter Herminio Pedraza. Suárez Weise used Pedraza's characteristic, colourful depictions of women to inform her elegant ‘Halo’ collection. Rich, vibrant violet gowns worn off the shoulder paid homage to the master painter who died in 2006.

‘My “prêt-à-couture” brand works with the same artisanal ways of making couture, but in an accessible product.’

—Ericka Suárez Weise

Now busy working in her atelier for a forthcoming collection, Suárez Weise is drawing inspiration from the indigenous Mojeños people from Bolivia’s Beni department, who perform the traditional machetero dance with large headdresses made of the plumes of tropical birds. Translating this style into women’s fashion is painstaking work, but the results are stunning, and they’ll soon be on the runway for the world to see – and perhaps, soon, we’ll be treated to the sight of a Hollywood actress wearing an Amazonian-headdress-inspired creation on the red carpet.

But for now, don’t look for a Weise gown at any boutique on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, or King’s Road in London. Her creations are not made for mass consumption. ‘I don’t want to have a huge brand now,’ she says. ‘I know I can’t – I know my limitations with production. I cannot go to Fashion Week and produce 10,000 pieces – no, this is not my situation. I am working with unique pieces, I am hoping we can reproduce 10 or 20 pieces. I have artisanal methods. It requires a lot of time, human time.’

Download

Download