‘¿Y su folder amarillo?’

The yellow folder, the ubiquitous sheet of manila paper folded in half that paceños clutch tightly and carry around and which becomes one’s most treasured possession, holds weeks, months, years of paperwork and administrative documents. It embodies the perseverance, resilience and determination of people in the quixotic task of facing Bolivian bureaucracy. I carried mine for nine months last year, regularly feeding it more letters, certifications and photocopies of these same letters and certifications. My adversary was the SERECI (Servicio de Registro Cīvico) in a quest to obtain my Bolivian national identity card.

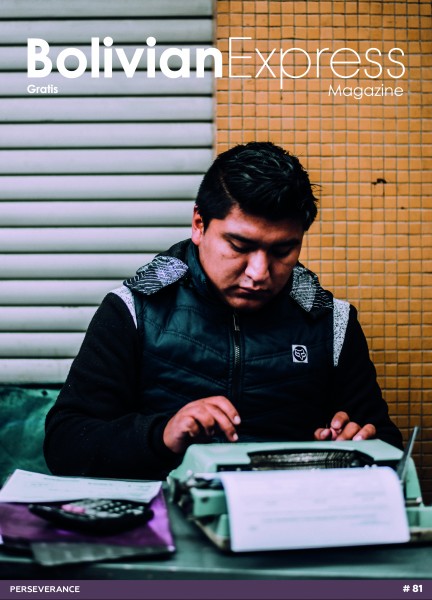

One of the ways that perseverance manifests itself in Bolivia is in the endless battle against a rigid and clunky administrative machine that loves legal documents, stamps, identification procedures and painstakingly long waiting lines. On the sidewalks in the centre of La Paz in a testament to an antiquated bureaucracy, typeadores use clunky typewriters to fill in forms and documents for the thwarted citizen who is simply trying to pay his taxes. One of our writers went to meet them, wondering how the future looks as Bolivia enters the digital age. We then talked to AGETIC, the governmental agency whose work aims to debureaucratize Bolivia’s administrative jungle, to ask them how they are tackling this dauntless task.

Alongside these typeadores are the caseritas, lustrabotas, aparapitas, afiladores and heladeros, who work in thankless and grueling professions and deserve the recognition that their perseverance entails. This is what we want to celebrate in this 81st issue of Bolivian Express: the constant and inspiring efforts of the people around us – the people who make Bolivia the incredible place it is.

One of these people is Leonel Fransezze, whose vision and motivation is to bring Bolivia’s artistic scene to the international stage. Because Bolivians have nothing to envy of their neighbours, it’s just a matter of hard work and perseverance – and it’s also a matter of changing a mentality of mediocrity. This can be achieved on a grassroots level, which is exactly what Simon Bongers and Ricardo Dávalos are doing with their international human-rights film festival, Bajo Nuestra Piel. We went to Tarija and witnessed rooms packed with school children watching documentaries about Madagascar and Cambodia and debating LGBT issues. Later on, we interviewed Bolivian trova band Negro y Blanco, who are working on a new album and whose mission has been for the last 20 years to paint a better future rooted in equality and love.

But, ultimately, change starts with oneself, which another of our writers experienced during parkour class in a physical show of fitness and determination as she conquered her body and environment – notwithstanding a few bruises.

My own personal and spiritual parkour (towards citizenship) involved being told that my parents had smuggled me out of the country as a baby (not true) and therefore I should start a trial against them (no), and that eventually Bolivia would adopt me with fabricated parents (that’s not how it works). I can’t recount the hours in line waiting to obtain some certification, legalisation, translation – which often wasn’t ready. A few more unexpected developments later, my administrative nightmare eventually came to an end, and with a favourable outcome. I could finally let go of my battered yellow folder, which, as it happens, did become my most cherished possession.

The motivations, and complications, of Bolivia’s UN bid for access to the Pacific

At the time of writing, it is early March. Headlines describing the construction of an originally 70-kilometre – now 200-kilometre – long banderazo pervade the papers; a grand poster of Bolivian President Morales backdropped against the sea overlooks Plaza Avaroa; flags symbolising the loss of el Litoral are draped ominously over several public buildings in preparation for el Día del Mar on the 23rd of the month. To the outsider, the overarching impression is greater than mere nostalgia or commemoration – around the statue of Eduardo Avaroa, the great defender of the Bolivian coast, there is an air of optimism, a gentle breeze of hope, of expectation.

The fervour with which Bolivia simultaneously commemorates and mourns her defeat at the hands of Chilean imperialism has hardly wavered over the past century. The undeclared annexation of over 400 kilometres of Bolivian coastline during the 1879-83 War of the Pacific, and the subsequent enclaustramiento of Bolivia, evidently remains impressed on the national consciousness.

In light of Morales’s decision to take the issue of the sea to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague in 2013, there appears to be an unprecedented sense of cohesion and strategy, a newfound competency to go with the intrinsic desire of every Bolivian for access to the Pacific Ocean. Former leaders, such as ex-president Carlos Mesa, have shelved their disputations and disagreements to aid the current government, and the Bolivian people remain united – galvanised – behind their country’s determination to return to the sea.

If you read El Libro del Mar or watch El Mar de Bolivia, both connected to the government’s campaign to return the sea to Bolivia, this is the overall impression you are left with. However, as with all campaigns built on patriotism, it is not until one digs a little deeper that the complexity and diversity of the issue become apparent.

In contrast to the misleading homogeneity of opinion propagated by the current government, public attitudes towards the possibility of returning to the sea are not so much divided as they are diverse. Around Plaza Avaroa, hope is intermixed with pessimism, passion with indifference, and a tangible uncertainty with new a degree of conviction.

‘¿Día del Mar? It’s simply a day,’ argues Julio from La Paz. ‘It’s a part of history and nothing more… We would have to reorganise the whole world otherwise.’

Although not many matched Julio’s candidness, his sentiment was not unorthodox in spite of some concrete support for the government’s current approach.

Pablo Palacios, a paceño who too is sceptical of the contemporary significance of el Día del Mar, is slightly less damning: ‘For me it is more like a dream than a real possibility.’ Yet, in response to the impact of Morales’s recent calls for international support, he agrees that it’s ‘more real than before.’

This micro-sample of opinions from locals around Plaza Avaroa certainly highlights the contemporary cultural and political complications behind Bolivia’s relationship to the sea, again in contravention of the government’s comparatively simplified narrative. With oral hearings set to take place between 19th and 28th of March of this year, Professor Alexis Pérez, an historian who specialises in Bolivian history, stresses the complexity and difficulty of the task ahead for the Bolivian government. ‘It’s not evident that Bolivia is getting any closer to regaining access to the sea since the 1904 treaty [which formalised the de facto armistice between Bolivia and Chile],’ says Pérez. ‘The reality is [the ICJ in The Hague has limits…It cannot touch the sovereignty of Chile. The most it can do is promote the idea of a negotiations table between Chile and Bolivia…This idea goes as far back as the 1840s, when Chile first encroached on Bolivian territory following the discovery of guano deposits.’

The fervour with which Bolivia simultaneously commemorates and mourns her defeat at the hands of Chilean imperialism has hardly wavered over the past century.

However, according to Pérez, it is not only the limited jurisdiction of the ICJ that appears to undermine the government’s calls for international support against Chile. ‘Although there are countries that sympathise with Bolivia, this is mostly moral, brotherly support,’ says Pérez. ‘Another problem is the government’s despotic nature and its failure to seriously tackle narcotrafficking – this damages Bolivia's international reputation.’ In contrast, he adds, ‘Chile pulls more weight internationally.’

It is clear that the overruling of the 2016 referendum on term limits has to a limited extent damaged Bolivia’s reputation as a stable democracy, particularly as the international community observes the Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro, controversially tightening his grip on power. Likewise, Argentina, Brazil and Chile, all of which share a border with Bolivia and hold great weight in continental politics, have expressed concern with Bolivia’s failure to suppress the cocaine trade. However, the obstacles between Bolivia and sovereign access to the sea are even more deep-seated than this. As Pérez explains, ‘If our economy was strong the economic pressure would force Chile to sit down…Why is a port necessary? The transaction costs are high and this hurts our export sector. That’s it.’

In terms of international trade, Bolivia ranks 100th in the world with just over US$7 billion in exports per year. Considering that around 70% of these exports go to the Atlantic coast, while Bolivian gas is exported primarily to Brazil and Argentina, the economic arguments behind renewed access to the sea are not independently significant enough to warrant even a minor territorial rearrangement.

However, it is not only the possibility of Bolivia regaining access to the sea that is in question but also the reasoning behind the government’s plea to the ICJ.

‘This government has been weakened [by the 2016 referendum],’ says Pérez. ‘When you go to The Hague you make your plea, you send your representatives, but they are sending half the government…They are using this nostalgia for the sea to manipulate the people.’

Although the current government’s original motives behind the appeal to the ICJ in 2013, two years before the controversial referendum on term limits, were most probably not rooted in a need to appease a discontented electorate, it is evident that the sea has become more important as a unifying force. As evidenced by the mass protests across Bolivia, both for and against Morales, that have commemorated the referendum of February 2016 in each of the last two years, Bolivian domestic politics are, as Pérez argues, ‘very questionable.'

Considering the inextricably complex and difficult reality, and Bolivia’s current democratic uncertainty, the unshakeable confidence and absolute commitment of the government in their bid to regain access to the sea appears even more politically expedient.

‘The government is using this nostalgia for the sea to manipulate the people.’

—Historian Alexis Pérez

‘Our presence in The Hague is going to cost between US$6-7 million. It’s expensive when the country has so many problems,’ asserts Pérez. ‘A lot of people call me a pessimist, but I think I'm a realist.’

Although it is evident that the loss of the sea carries great historical and cultural importance in Bolivia, one can be forgiven for being sceptical of the current government’s capacity to find a political and economic agreement with Chile, with or without the multilateral pressure of the ICJ. Not only are there doubts to be had about the implementation mechanisms of any favourable verdict, but there are also doubts as to the competency – and motivations – of the current government. Thus Bolivia’s return to the sea is neither straightforward nor simple despite the apparent reinvigoration of optimism among some Bolivians. The sea evidently remains embedded in the collective consciousness of Bolivia; however, whether this strength of sentiment will translate into a viable political solution between Chile and Bolivia remains as opaque as it has for more than a century.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez Petkovic

‘Si es que crees en mi canto haz de Bolivia tú también

y ven a unir conmigo tu esperanza y tu fe’

‘If you truly believe in my song, make Bolivia yours as well

And let your hope and faith unite together with me’

These are the powerful lyrics of Negro y Blanco’s patriotic and most acclaimed song, ‘Píntame Bolivia.’ The song, which was a highlight of Negro y Blanco’s recent performance of trova music at La Paz’s La Trovería bar, expresses a sense of solidarity, a love for Bolivia and conveys a timeless pledge for equality, hope and peace.

At La Trovería, the concert was staged in a dark, small and intimate setting. Tables were covered with images of trova lyrics and seated an audience that wholeheartedly sang along to many of Negro y Blanco’s classics. The band, composed of Christian Benítez and Mario Ramírez, aims to communicate universal notions of peace, love, solidarity and a respect for human rights through music. The duo’s voices were calming and melodious, rendering the messages of their songs more powerful. The harmonious combination of two sole guitars and two voices added to the intimacy of the bar.

Trova is a musical genre that originated in France, whereby French troubadours would sing poems in courts for the nobility or at musical contests. This genre was later adopted in Cuba as ‘Nueva Trova’, often expressing fraught emotions such as dissent, hatred, love and affection towards society or right-wing political regimes during the 19th and 20th centuries. Trova music became popular in Bolivia during the 1960s and 1970s, upholding the romantic and sentimental ideals that characterise Negro y Blanco’s music.

Bolivia’s past is marked by Spanish colonialism, racism, poverty and exploitation of indigenous people. ‘Poverty has always been widespread in Bolivia,’ Ramírez says. According to Benítez, since Bolivians embodied racial wounds following events in the 1960s and 1970s, self-analysis and introspection are paramount for the country’s healing. Trova, Benítez believes, provides a therapy for curing such wounds.

Negro y Blanco began recording their songs during the 1990s in La Paz and released their first album in 1998. Having grown up under ex-dictator Hugo Banzer in the 1970s, Benítez remembers the challenges that his family and peers faced during that period. Popular music conveyed what was happening at the time. It was ‘death and destruction,’ he says. This inspired the band to promote a message of peace through their songs. Since Bolivian songwriters and singers of protest music had left the country by the 1990s, the band saw an opportunity to bring about change through its artform. Seeing Bolivia as ‘a little laboratory’, the duo believes that such change could happen through trova music.

Ramírez and Benítez started out singing and songwriting as a hobby during their university years. Benítez recalls growing up to the songs of acclaimed Cuban trova singer Silvio Rodríguez and how he immediately fell in love with them on the radio. In retrospect, he says it was his mother’s way of indirectly educating him about music.

When the duo decided to pursue a career in music, both of their families were taken by surprise. But the band persisted in its songwriting and in its goal to ‘demolish walls and construct bridges’ through music, building a ‘better future’ for Bolivians.

During the 1990s and the early 2000s, the band began working with younger generations in La Paz as the founders of a movement called Guitarra en mano. ‘We called it a colectivo,’ Ramírez says. The aim was to write music together and constructively discuss pressing social concerns. It lent a voice to the younger generations and was a different way of seeing reality in La Paz, El Alto, Cochabamba and Santa Cruz. Although the band has produced three albums (‘Negro y Blanco’, ‘Negro y Blanco en Blanco y Negro’ and ‘El Negro y Blanco en la Fiesta’) it has also recorded compilations for social causes such as women’s rights and the environment.

Now, almost 20 years later, the band is about to release an anniversary album that features new music as well as songs that were written 15 years ago but never officially recorded or released to the public. For Benítez, Bolivia is a melting pot of diverse races, cultures, customs and traditions. Both artists hope to continue promoting integration and peace through trova music that ‘touches the human heart’ and creates a positive future.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez Petkovic

The drive and philosophy of the city’s fearless tracers

Prepare, run, jump, soar, reach, kick, grab knees and…’Ahhh!’: I smash face-first into the crashmat, emitting an embarrassing squeal. Swallowing my pride, I slope over to my instructor.

‘Look, Sophia, we’re doing the Webster, that’s a front-flip, but you’re turning and attempting a different move, called the Side,’ he says. ‘Oh, sorry,’ I reply, to which he quickly retorts, ‘No, it’s fine! I think you’re better at the Side. Watch and copy.’

He approaches the mat at a trot and effortlessly floats up into the air, spinning around a couple of times and landing softly on his feet. The entire class bursts into guffaws at the idea of me imitating such grace, myself included.

This is my third parkour class at the Spazio gym in Sopocachi, and whilst I am improving, the journey ahead is long and peppered with bruises. Nevertheless, when I found out that my local gym gave parkour classes, no one could have kept me away. La Paz never fails to deliver when it comes to enthralling juxtapositions, such as an underground subculture sport being taught at a mainstream (and pretty high-end) gym.

The discipline of parkour has undertaken a long and transformative voyage to arrive in the plazas of La Paz. It started as a French military training technique, parcours du combattant. It was then developed by David Belle, the son of a military man, who brought parkour to fame through gravity-defying stunts and his tight-knit community. Henceforward, the sport follows the traditional narrative of a subculture: the development of principles, a philosophy, in-fighting, a split between orthodox and globally-focused practitioners and finally, a nudge into the mainstream.

However, parkour did not arrive in Bolivia by jumping and vaulting across the Atlantic, nor did its philosophy take root through the evangelisation tactics of missionaries. Parkour hitched a ride to the heart of South America on the back of social networks. Within the past decade a community has arisen from provocative YouTube videos, gifting the country several parkour and freerunning teams, a handful of academies and a one-hundred-strong community in La Paz.

‘It’s more of lifestyle than a sport.’

—Mauricio Pizarro, parkour instructor

One such practising paceño is my instructor, Mauricio Pizarro, a 24-year-old architecture student and a member of No Limits, Bolivia’s first freerunning and parkour collective. His journey started just under three years ago when he came across a few videos on YouTube that sparked his interest. Pizarro then found the Parkour La Paz group on Facebook and was thrilled to discover that it was a community of parkour practitioners or ‘tracers.’ These people helped him develop skills as well as a new attitude towards life. ‘Parkour is not solely a physical sport,’ Pizarro is keen to impress upon me, ‘it’s also mental and spiritual. To pull off a jump you have to be physically, spiritually and mentally ready for it.’

The philosophy of parkour is one of overcoming fears, competing with oneself rather than with others and seeing obstacles as opportunities for creativity and growth. It’s a way of changing the way you see and interact with your surroundings. When you are surrounded by the spectacularly twisted, layered and chaotic urban landscape of La Paz, the chances to get creative are seemingly infinite. Pizarro’s tone quickens and he begins to gesture enthusiastically as his two fields of expertise collide. ‘Geologically,’ he says, ‘[La Paz] is a city of ups and downs which has forced the architecture to adapt. Before the teleférico you’d have to go down thousands of little stairs, slopes and…’ he trails off, waving his hands in excitement at the wealth of parkour-perfect areas in the city.

The defining factors of Pizarro’s approach to parkour seem to be inclusivity and spirituality. The former inspires the open-to-all access of his classes and his strong sense of personal competition, while the spirituality is present in his words, his story and his resolve. When he started out he was going through a difficult stage of his life and his personal practice and the parkour community helped him surpass his fears. ‘I associate [parkour] a lot with life. If you’re confronted with a barrier, you don’t avoid it you cross it,’ he says. With this mentality it is easy to see how a person can be empowered; no longer a victim to their surroundings but an actor, interacting with and exploiting their environment.

I vault myself onto the gym horse, put out two hands and roll off the second obstacle, landing stably on my two feet. Looking down, I see two new shiny bruises on my knees from where I mistimed my jumps, and I haven’t even made it out of the gym yet. Nevertheless, I am inspired by the dedication, openness and the values of La Paz’s tracers. Perhaps this admiration will transcend into jumping over stray dogs and hurdling kiosks as I trace my way around Sopocachi.

Download

Download