‘¿Y su folder amarillo?’

The yellow folder, the ubiquitous sheet of manila paper folded in half that paceños clutch tightly and carry around and which becomes one’s most treasured possession, holds weeks, months, years of paperwork and administrative documents. It embodies the perseverance, resilience and determination of people in the quixotic task of facing Bolivian bureaucracy. I carried mine for nine months last year, regularly feeding it more letters, certifications and photocopies of these same letters and certifications. My adversary was the SERECI (Servicio de Registro Cīvico) in a quest to obtain my Bolivian national identity card.

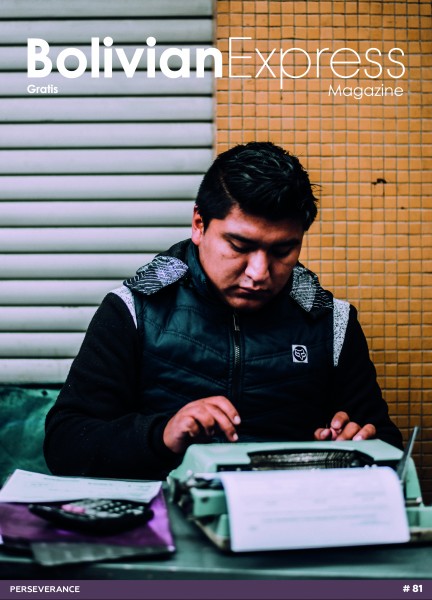

One of the ways that perseverance manifests itself in Bolivia is in the endless battle against a rigid and clunky administrative machine that loves legal documents, stamps, identification procedures and painstakingly long waiting lines. On the sidewalks in the centre of La Paz in a testament to an antiquated bureaucracy, typeadores use clunky typewriters to fill in forms and documents for the thwarted citizen who is simply trying to pay his taxes. One of our writers went to meet them, wondering how the future looks as Bolivia enters the digital age. We then talked to AGETIC, the governmental agency whose work aims to debureaucratize Bolivia’s administrative jungle, to ask them how they are tackling this dauntless task.

Alongside these typeadores are the caseritas, lustrabotas, aparapitas, afiladores and heladeros, who work in thankless and grueling professions and deserve the recognition that their perseverance entails. This is what we want to celebrate in this 81st issue of Bolivian Express: the constant and inspiring efforts of the people around us – the people who make Bolivia the incredible place it is.

One of these people is Leonel Fransezze, whose vision and motivation is to bring Bolivia’s artistic scene to the international stage. Because Bolivians have nothing to envy of their neighbours, it’s just a matter of hard work and perseverance – and it’s also a matter of changing a mentality of mediocrity. This can be achieved on a grassroots level, which is exactly what Simon Bongers and Ricardo Dávalos are doing with their international human-rights film festival, Bajo Nuestra Piel. We went to Tarija and witnessed rooms packed with school children watching documentaries about Madagascar and Cambodia and debating LGBT issues. Later on, we interviewed Bolivian trova band Negro y Blanco, who are working on a new album and whose mission has been for the last 20 years to paint a better future rooted in equality and love.

But, ultimately, change starts with oneself, which another of our writers experienced during parkour class in a physical show of fitness and determination as she conquered her body and environment – notwithstanding a few bruises.

My own personal and spiritual parkour (towards citizenship) involved being told that my parents had smuggled me out of the country as a baby (not true) and therefore I should start a trial against them (no), and that eventually Bolivia would adopt me with fabricated parents (that’s not how it works). I can’t recount the hours in line waiting to obtain some certification, legalisation, translation – which often wasn’t ready. A few more unexpected developments later, my administrative nightmare eventually came to an end, and with a favourable outcome. I could finally let go of my battered yellow folder, which, as it happens, did become my most cherished possession.

A film festival pushes boundaries in Bolivia

On 22 February 2018, the third edition of the international human-rights film festival Bajo Nuestra Piel visited Tarija, in southern Bolivia. Having premiered in La Paz in November 2017 with stops in El Alto, Potosí and Tarija, the festival is now touring to Coroico in April, followed by Camiri, in the Santa Cruz department.

Founded in 2016 by Simon Bongers and Ricardo Dávalos, the project originated in Oruro in collaboration with the local university and schools in an effort ‘to generate a debate and reflective space on human-rights topics through the artistic representation in the documentary, fiction and animation formats, of critical, socially comprised and quality cinema.’ Two years later, Bajo Nuestra Piel has an international selection of over 90 movies, including some Bolivian productions, presenting them free of charge in all locations.

Bongers’ vision and inspiration can be best summarised in the name of the festival itself: ‘There are some stories that can be written in books and others...under our skin,’ Bongers says. ‘We are all the same…We are all connected.’ He says there haven’t been any major obstacles in organising the festival, but the challenge remains as to ‘how to reach people who are not interested or aware of human rights.’

‘There are some stories that can be written in books and others...under our skin.’

—Festival organizer Simon Bongers

From its inception, a main focus and driving principle of the festival is working with local schools to show stories that connect people. To that end, with the help of the Tarija municipality and schools, buses were commissioned to transport students to the screenings, who buzzed with excitement in anticipation of a school trip and the thrill of the unknown. One of the documentaries shown, Iron Legs, about lesbian girls on a Cambodian football team, introduced the students to a theme that is not usually broached in Bolivian society. Reactions were aroused during the screening and led to a slightly uncomfortable but necessary conversation on LGBT issues in Bolivia.

After the screening, Bongers led a question-and-answer session about the similarities on screen and in the teenage audiences’ lives. Most showings are followed by a discussion and debate with the audience, who interact with invited moderators. Bongers hopes to reach people who wouldn’t otherwise go to the cinema of their own volition. He wants to show perspectives and tell stories, which, although they are often undiscussed by audience members, are not so different from their own.

Reactions were aroused during the screening and led to a slightly uncomfortable but necessary conversation on LGBT issues in Bolivia.

As the festival travels around Bolivia, Bongers adapts the selection to make it relevant to the different cities visited. The next stop for Bongers and his team of volunteers is Coroico at the Unidad Académica Campesina-Carmen Pampa in the Yungas, from 4 to 8 of April. Films will be shown at the university in Carmen Pampa during the day, and, if the weather allows, there will be open-air screenings in Coroico. All showings are completely free, and all are welcome.

Contact: festival@bajonuestrapiel.org

For more information, see the Bajo Nuestra Piel website at www.bajonuestrapiel.org.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

AGETIC: The Electronic Government

The process of dismantling bureaucracy is often no less futile than erasing a sentence with a highlighter. Sometimes, in the name of debureaucratization, anti-bureaucracy bureaucracies are created, anti-bureaucracy bureaucrats are recruited, and the overall amount of bureaucracy remains the same, if not larger than before.

In Bolivia, where bureaucracy is almost as prevalent as it is in the preceding paragraph, such a process has begun. But such is the endemic and anachronistic nature of Bolivian bureaucracy, that there appears to be the possibility of genuine and significant change.

The arduous and lengthy task of modernising the Bolivian state is being undertaken by AGETIC (Agencia de Gobierno Electrónico y Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación) – a government department created in September 2015 for the specific purpose of debureaucratization. Nicolás Laguna Quiroga, the director of the agency, is clear and frank about the reality of Bolivia’s superfluity and inefficiency, as well as the aims of AGETIC.

‘It’s true the state is stuck in practices from 20, 40, sometimes a 100 years ago,’ he explains. ‘From now on it is a process of penetration, change and transformation…We are trying to transform the technological reality and logic of the state.’

Since its inception, an open data system, a centre for security, and over 20 new information systems for various institutions to work with have been developed, to replace the considerably smaller 15-staff ADSIB (Agencia para el Desarrollo de la Sociedad de la Información), setting the foundations for what the agency terms: ‘El Gobierno Electrónico Soberano.’

As Laguna points out, AGETIC, being a part of the Ministerio de la Presidencia, now has the institutional and financial support for significant change; a type of change, argues Laguna, that comes from the people of Bolivia.

Although still a nascent organisation, there has been enough progress with AGETIC to vindicate Laguna’s optimism. Since it became operative in January 2016, a platform for paying online has been developed along with an identification system for people to have the same ID and password for all state-related issues – tools intended to facilitate easier interaction between the people and public services.

‘[AGETIC] comes from the necessity of the state to adapt to the changes in society…67% of Bolivians are internauts. People want results,’ Laguna explains.

However, although methods of communication and social interaction have fundamentally changed for many Bolivians in recent years it remains to be seen whether this will translate into an overhaul of economic and political practices. According to government figures, though 83% of Bolivian internauts use the Internet to connect with friends and family, only 4% of them shop online.

This disparity in the uses of the internet certainly poses challenges to AGETIC’s aims for 2025, coinciding with the bicentenary of Bolivia, which even Laguna admits are ‘ambitious.’

‘Everything will be online,’ he says. ‘70% of Bolivians will interact with the government online and the proportion of Bolivians using online payments will rise from 10 to 70%. There too will be a significant rise in electronic commerce which will help economic growth.’

These targets are made yet harder by the existence of several bureaucratic obstacles – embedded in tradition and routine of the public service – that remain stubborn and rigid, particularly regarding public organs independent of the executive, such as the judiciary. Thus, although various software and technological instruments have been developed, their implementation has in some cases stalled.

‘The public authorities are very closed, they only think about themselves,’ Laguna continues. ‘They manage their own administration, their own procedures and they don't care about the citizen.’

This sentiment encapsulates the outlook of AGETIC. Not only is the deconstruction of bureaucracy necessary in the increasingly globalised and tech-orientated world in which we live, but it is also a process rooted in the tumult of Bolivia’s history.

As Laguna explains, ‘[bureaucracy in Bolivia] is a legacy from colonial times, a bureaucratic apparatus that the republic inherited, a nucleus of Spaniards and criollos that ignored the indigenous world.’ But for him, ‘the priority is the citizen.’

This too is reflected in the approach of AGETIC. ‘Everything we create is turned into free software with the purpose of public use,’ Laguna says. ‘For us this is more than just a project. What we want is to serve the people…We want to learn and do it ourselves.’

Thus, the process of debureaucratization in Bolivia, although long and inevitably attritional, is underway. Whether AGETIC can retain its focus and coherence of approach in the face of both tradition and systematic stubbornness remains to be seen. Laguna, however, is positive that the change will come: ‘The future is here.’

The Typeadores

Amid the bustle and busy bureaucracy of La Paz’s administrative centre, tucked away among small market stalls and purposeless tourists, the typeadores sit at their antiquated typewriters, typing up impuestos and other official documentation. Their clients are pedestrians, their offices are the streets.

Showcasing his new typewriter, engraved ‘Made in the Democratic Republic of Germany’, Benancio Maica, 60, explained the role of the typeadores:

‘What we mostly do is fill forms, tax forms, everything related to taxes.’

Despite the mundanity of their work, the typeadores, who have been working in the streets of La Paz since 1986, certainly add a quirkiness to Bolivian bureaucracy, working all year through ‘the cold, the wind and the rain.’

When asked if he believed the typeadores were under threat from technological advancement Maica was both confident and resolute:

‘Typewriters are easier and more practical than computers – we can take them anywhere. Our clients know us…The typewriters will live on.’

Photo: Iván Rodriguez Petkovic

Translation: Niall Flynn

Parents and protectors of the Andean world

¡Tatituy! ¡Papituy! These are the words that the yatiri repeats, referring to the ancestral spirits and protective parents from the mountains. He graciously makes a blessing to bring good fortune in work, study and love. Ramón Quispe is an Aymara yatiri who believes in the protection and blessings of the mountain spirits called Achachilas.

The Achachilas are supernatural spirits of the Andean world and the protectors of Aymara communities. These spirits inherently exist or reside in the mountains and the snow-covered altiplano.

The city of La Paz is stunningly located, picturesquely positioned in a canyon surrounded by mountains in the western cordillera of the Andes, with the Cordillera Real lying to the northeast. There are three magnificent summits which stand out along the mountain belt: the snow-capped Illimani, Illampu and Huayna Potosí. These mountains are spirits with a mighty jurisdiction. According to Ludovico Bertonio, a Jesuit priest and linguist who was a pioneer in the study of the Aymara language, the Achachilas are grandparents, ancestors or the sage of the household.

One of the most important Achachilas is Illimani, a snow-covered peak at 6,438 metres above sea level. The name derives from the Aymara word illa, which means ‘generator of plenty’, and mani, which comes from mamani, meaning ‘protector’. This was the name bestowed by the various ayllus, or Aymara communities, that once inhabited the vicinity of Chuquiago Marka – now the city of La Paz.

The Achachilas are of great importance, and the Aymara believe in a hierarchy of deities. However, all the spirits that form part of the Aymara belief system are worshipped through different rituals, such as the Challas festival in August and Carnaval, as well as the dinners or offerings that are made to Pachamama, and the Achachilas are similarly conjured for protection.

‘On 3 May in Puerto Acosta [a town near Lake Titicaca], there is a festival dedicated to the Auki Auki, who represent the Achachilas in human form; the Aukis embody the Achachilas so that they can share and partake in the community. Three or four people are chosen to personify the Achachilas, which allows them to celebrate and dance in the earthly world,’ Varinia Oroz, a curator at La Paz’s National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore, says. The Aukis make sexual gestures, indicating that they are fertilising the land to ensure a good harvest. These notions of fertilising the earth and the agricultural calendar are present in various community celebrations, whereby the gods are summoned and personified to protect and enrich the earth.

When walking along the traditional calle de las Brujas, or ‘Witches Street,’ in La Paz, you can find figuries in the form of elderly figures, men and women who embody the Achachilas. People place them in their houses for blessings and protection. Likewise, there are songs and dances of adoration for these figures.

As one of seven designated wonder cities of the world, La Paz is undoubtedly becoming an enigmatic and unique realm to explore.

Download

Download