‘¿Y su folder amarillo?’

The yellow folder, the ubiquitous sheet of manila paper folded in half that paceños clutch tightly and carry around and which becomes one’s most treasured possession, holds weeks, months, years of paperwork and administrative documents. It embodies the perseverance, resilience and determination of people in the quixotic task of facing Bolivian bureaucracy. I carried mine for nine months last year, regularly feeding it more letters, certifications and photocopies of these same letters and certifications. My adversary was the SERECI (Servicio de Registro Cīvico) in a quest to obtain my Bolivian national identity card.

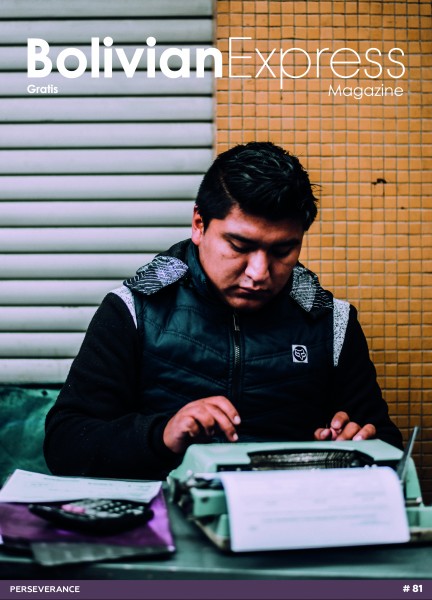

One of the ways that perseverance manifests itself in Bolivia is in the endless battle against a rigid and clunky administrative machine that loves legal documents, stamps, identification procedures and painstakingly long waiting lines. On the sidewalks in the centre of La Paz in a testament to an antiquated bureaucracy, typeadores use clunky typewriters to fill in forms and documents for the thwarted citizen who is simply trying to pay his taxes. One of our writers went to meet them, wondering how the future looks as Bolivia enters the digital age. We then talked to AGETIC, the governmental agency whose work aims to debureaucratize Bolivia’s administrative jungle, to ask them how they are tackling this dauntless task.

Alongside these typeadores are the caseritas, lustrabotas, aparapitas, afiladores and heladeros, who work in thankless and grueling professions and deserve the recognition that their perseverance entails. This is what we want to celebrate in this 81st issue of Bolivian Express: the constant and inspiring efforts of the people around us – the people who make Bolivia the incredible place it is.

One of these people is Leonel Fransezze, whose vision and motivation is to bring Bolivia’s artistic scene to the international stage. Because Bolivians have nothing to envy of their neighbours, it’s just a matter of hard work and perseverance – and it’s also a matter of changing a mentality of mediocrity. This can be achieved on a grassroots level, which is exactly what Simon Bongers and Ricardo Dávalos are doing with their international human-rights film festival, Bajo Nuestra Piel. We went to Tarija and witnessed rooms packed with school children watching documentaries about Madagascar and Cambodia and debating LGBT issues. Later on, we interviewed Bolivian trova band Negro y Blanco, who are working on a new album and whose mission has been for the last 20 years to paint a better future rooted in equality and love.

But, ultimately, change starts with oneself, which another of our writers experienced during parkour class in a physical show of fitness and determination as she conquered her body and environment – notwithstanding a few bruises.

My own personal and spiritual parkour (towards citizenship) involved being told that my parents had smuggled me out of the country as a baby (not true) and therefore I should start a trial against them (no), and that eventually Bolivia would adopt me with fabricated parents (that’s not how it works). I can’t recount the hours in line waiting to obtain some certification, legalisation, translation – which often wasn’t ready. A few more unexpected developments later, my administrative nightmare eventually came to an end, and with a favourable outcome. I could finally let go of my battered yellow folder, which, as it happens, did become my most cherished possession.

Illustration: Jumataki

An entrepreneurial cooperative supports small-business women

The mañaneras set their cloth and artisan goods up on calle Illampu by 6.30am in the early morning, sell throughout the day, and then, upon their dismissal by the police (for occupying space not belonging to them), they carry their loads back to El Alto, or even farther into the altiplano. The strong work ethic of these women, their dedication to bartering and business, can be an inspiration to all.

Many other empowered Bolivian women are now inspired to find new ways to make their living through a cooperative called Jumataki. Initiated in May 2014, its name means ‘for you’ in Aymara. Two of the cooperative’s 30 members, Maruja Laura Gómez and Olga Bustillos, sew impressive, intricate designs onto telas that can be used for tablecloths or bedspreads. Other Jumataki members produce other creative goods and administer the business side of the members’ ventures.

Another member, Virginia Condori, runs a laundry service in the Centro de Modas in the Calacoto neighbourhood of La Paz’s Zona Sur. Jumataki grants women the flexibility to work from home as well as in its office on calle 21. This allows its members to look after their families as well as to learn new skills from each other. Jumataki offers flexibility for women and encourages them to use their creativity in an entrepreneurial manner.

Many empowered Bolivian women are now inspired to find new ways to make their living.

Artisan Olga Bustillos appreciates this flexibility of lifestyle that Jumataki offers to its members. Having worked in this field since 1985, when she was 13 years old, she mentions that she does not need to sacrifice family time to her job. The ease of seeing her children and working from home when she wants to give her a comfortable lifestyle. ‘I don’t lose out either way,’ she says.

Bustillos and Laura Gómez say their clients appreciate the skill involved in their work, which can be time-consuming. For example, a bedspread or tablecloth can take up to one month to complete. ‘It’s a killer,’ Bustillos says about her work that requires so much skill and concentration.

The members of Jumataki have solidarity with one another, and, as one member says, ‘no one abandons us.’

For Bustillos, what she values most is the social aspect of her job, in which she negotiates with customers and works with women who share similar lifestyles to her. The members of Jumataki have solidarity with one another, and, as Bustillos says, ‘no one abandons us.’ Her customers come every day to purchase her goods, and her job she says, is so much more worthwhile than ‘being trapped between the four walls of my home.’

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

The impresario wants Bolivia’s creative community to come into its own

If you live in La Paz, chances are you’ve walked past a picture of Leonel Fransezze on a billboard advertising mentisan or sunglasses, or maybe you’ve seen him on TV as a presenter on ATB, or in the newspapers’ society section. His ubiquitous presence is hardly surprising once you’ve met the man. His energy, charisma and insatiable ambition make him one of the most notable people of his generation.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1985, he grew up in La Paz before leaving to study theatre in Argentina at 18, coming back to Bolivia in 2013. His last five years have been prolific, to say the least. His first vocation is in the theatre. His roles have included Dracula and Javert from Les Misérables, but his ambition extends much further. His goal is to ‘make Bolivia and Bolivia’s talents known in the world.’

To do this he started the company Macondo Art with Claudia Gaensel in 2014. It’s a multidisciplinary enterprise that dabbles in theatre, audiovisual arts and event organising. The company’s goal is to promote Bolivian arts, producing quality shows and raising the standards of the creative arts in Bolivia. In the last four years, Fransezze says, ‘We have more than tripled the public of the municipal theatre in La Paz…We have increased the level of quality of national shows.’

Fransezze is now working on another project: a Bolivian TV miniseries, La Entrega. According to him, it took 16 weeks of filming, one of the longest shooting projects in Bolivia, and will comprise 10 episodes. La Entrega tells the story of human trafficking in Bolivia, and, says Fransezze, ‘It doesn’t have anything to envy from foreign productions.’ Fransezze is aiming to sell it to international networks like Fox and HBO, but, in any case, he says, ‘I can assure you it will come out internationally.’ He also has a movie in works for later this year, about which he can’t say much.

When talking to Fransezze and seeing the determination in his eyes, it’s clear that he’s achieved all of this through raw effort and perseverance. His motto, he reveals, is that ‘When people tell me I can’t do it, it means that I will be able to do it.’ ‘You have to go ahead without expecting someone to push you,’ he says. Making mistakes and failing aren’t to be feared, as ‘failing is the only way to grow.’

I ask how Fransezze overcomes all the challenges on his way to achieve his many artistic visions. The answer is simple: ‘With perseverance. With failures and perseverance. You have to remove these mental paradigms: There are walls, barriers against success – we put them up ourselves.’ One of the main obstacles he aims to overcome is changing the default setting for Bolivian mentalities. ‘One thing is to change the mind-set, remove the chip that says that because we are Bolivians and it’s a small country we can’t do great things. We’ve all said something like “This is good…for Bolivia.” We’ve all said it, and there’s nothing more mediocre than saying this. When we ourselves put up this barrier – “Bolivia low-quality” – we’re lowering our ceiling so we can’t stand up. We have to stop talking like mediocrities, and we have to start talking like winners.’

And there’s also been personal fights that Fransezze has had to overcome. Because he wasn’t born in Bolivia, people who want to attack him use this as an excuse to deride him. This was hurtful at first but not anymore, as it’s pretty clear for Fransezze who he is and where he belongs: ‘I am en mi tierra. I lived in Bolivia since I was six years old. I am Bolivian according to the law and in my heart. In Argentina they called me bolita, I’ve always been the stranger. I can’t go to any place without being the stranger. I am never in my country, according to people. Gaucho [in Bolivia], bolita [in Argentina].’

Ultimately, Fransezze concludes, ‘The hardest is to start something…because then it’s like a snowball effect. At the beginning it was difficult to show sponsors that we had quality products.’ Now Macondo Art is a well-established company which was involved in projects amounting to US$700,000 last year. Fransezze’s hard work and perseverance has been paying off, but he doesn’t take all the credit. He says that the most important secret to success is to have ‘a good team to succeed. And to surround yourself with people more capable than you.’ Today, for Fransezze, ‘the future looks beautiful, very promising…I am anxious, I want to see results already, but it’s a process that takes years. What you need is patience, and to have a very focused objective.’

Illustration: Maz Cul

A review of a satirical take on suicide

Absurdist, perverse, comical, creative, insightful: 21 Maneras de no Suicidarse, or 21 Ways Not to Commit Suicide, is both an humorous and at times deftly perceptive exploration of suicide. Conceptualised by Nicolás Ewel and Pablo Quiroga, it features voluntary contributions of 21 artists from across Bolivia and beyond.

Unlike typical romantic portrayals of suicide in art, the success of this short book – eclectic as it is – lies in the comical absurdity of its ideas and the blunt surrealism of its images, with each artist presenting an unorthodox way not to commit suicide.

‘There is no purpose to the book,’ explains Quiroga. ‘I suppose it's kind of a satire of self-help books. Nobody asked you to be alive… Death, after all, is an inevitable end.’

Masturbarse efusivamente by: Carmen Fonseca

It is within these nihilistic precincts that the surrealism of the work, so to speak, comes to life, creating an artistic rawness so outlandish and imaginative that when flicking through the book one is almost absorbed into the comical depictions of suicide – an intended consequence of the work. ‘We didn't want the pressure of having an objective,’ adds Quiroga, ‘but in some sense we wanted to challenge the taboo of suicide… It's black humour, I suppose.’

This implicit intention is reflected in the overall design of the book. Although the images are ordered one through twenty-one, the chronology is largely chaotic and disordered. The simplicity of the pallet, in which all but one of the 21 works are devoid of colour, serves to define and re-emphasise the zaniness of the black-on-white images. As one moves through the various unorthodox methods of suicide, from ‘Freir un Huevito’ (‘Frying an Egg’) by Mar&Ana, to ‘Masturbarse Efusivamente’ (‘Masturbate Effusively’) by Carmena Fonseca, initial bemusement quickly moulds into immersive comedy, such is the absurdity and innovation of the body of work.

The 11th image, ‘Ver El Atardecer’ (‘Watching the Sunset’) by Perro Florindo, provides the reader with a brief recluse from the black and white surreality of the other works. Mercurial shades of blue sink into one another as the golden sunset seeps from the clouds across the two-page night sky. When asked why there was this anomalous splash of colour in the middle of the book, Quiroga explains, ‘It's kind of like an interval between the blackness.’ It is a moment of relief and reflection before one is quickly absorbed back into the absurd and twisted imaginations that colour the remainder of the book.

Imaginar by Juan Carlos Porcel

Although there have been a few criticisms of insensitivity, particularly regarding the works captioned ‘Patear un Niño’ (‘Kicking a Child’) by Smoober and ‘Iniciar una Familia’ (‘Starting a Family’) by Ciello Belo, such criticisms appear to misunderstand the body of work. As Quiroga clarifies, ‘The book does not give reasons to commit suicide’; it does not condone, nor condemn. It merely attempts – and often succeeds – to comically portray the futility of existence and the forever blurred, purposeless analogue between life and death.

‘La muerte acompaña la vida y es constante en el vivir.’ Nicolás Ewel.

‘Death accompanies life and is a constant in living.’ Nicolás Ewel.

For sale at: Cafe Typica, Calacoto and Sopocachi.

Contacts: Pablo Quiroga: 76730194 - pablo.crepas@gmail.com

Nicolás Ewel: nicoewelclaros@gmail.com

Download

Download