In the West, Christmas is a fusion of pagan and Christian celebrations. In Bolivia, end-of-year festivities coincide with the arrival of the rainy season and the summer solstice, events that were vital for the agricultural pre-Columbian civilisations that ruled the continent. Today, the combination of Christian and indigenous traditions makes for a very special type of holiday, with a syncretism that manifests itself in parades and traditional indigenous dances performed in front of pesebres. One of our Bolivian Express elves, Charles Bladon, explores the intricacies of a Bolivian Christmas on page 22.

Indeed, an essential element of Bolivian culture and celebration is dancing. The holiday season is punctuated with parades, carnivals and opportunities to perform dances learned in school. But in this fastpaced world that we live in, different cultures and celebrations have become intertwined, their meanings sometimes lost and often hidden behind layers of newer traditions.

Traditional dances evolve and slowly start to lose their original essence. The Ballet de Bolivia attempts to preserve the primary meaning behind these traditions by combining classical ballet techniques with indigenous Bolivian dance. Fruzsina Gál interviews Jimmy Calla Montoya, the company’s founder and the driving force behind these efforts, on page 30.

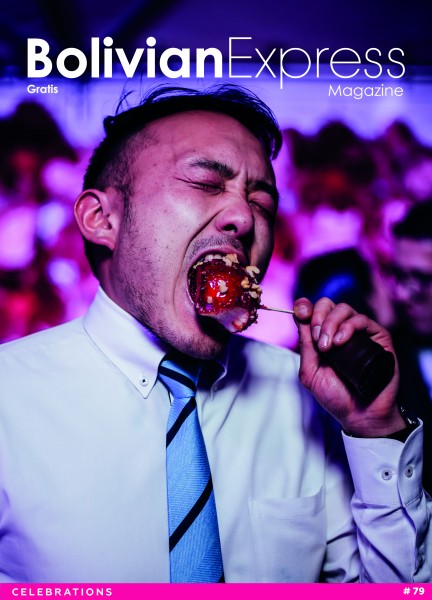

In this issue of Bolivian Express, the last of the year, we want to celebrate Bolivia and its ancient, vibrant and evolving culture. And we are looking at it through the eyes of a new generation of Bolivian artists such as the pop singer Andoro in addition to culinary pioneers and entrepreneurs who are putting Bolivia in the forefront of their projects. Daisy Lucker takes a look at the new restaurant

Popular, which puts a modern and inspired twist on Bolivian cuisine in the historical centre of the city. And it’s quite a success, as the restaurant’s founders deliver on their inspired idea to provide contemporary Bolivian food made by Bolivians with Bolivian products. Another entrepreneur, hotel Atix co-founder Carlos Rodríguez, is also profiled in this issue about the arduous path he took to create a successful business, on page 36.

Traditions and celebrations in Bolivia are a patchwork, an aguayo tapestry that reflects the diversity and unity of the people of Latin America. One item that tells this story like no other, and which is central to Christmas celebrations in Bolivia, is the panetón, a sweet bread traditionally eaten around Christmas and paired with hot chocolate. A ubiquitous feature of Christmas in Bolivia, the panetón is actually a recent import from Peru (and originally brought from Europe by Italian immigrants at the turn of the 20th century). You can now find panetones made with such Bolivian ingredients such as coca and quinoa, and they are part of each and every Bolivian Christmas canastón.

By celebrating Bolivian-ness, we are also embracing the multitude of influences that accompanies it: the variety and uniqueness of this culture, the foreign and diverse influences that have helped shape the country since its formation and that are part of all of us – Bolivians, tourists, expats and the rest.

Photo: Esteban Terrazas Saravia

La Paz. The sun dissipates and, with it, my urban trepidation. The night encroaches, accompanied by wonder and titillation. The night promises so much, the impossible seemingly possible only for one night.

Inside the clubs lights flash, momentary blindness followed by momentary exposure to the dance floor in its totality. Distinct booms, bass resonating to your very core inspiring movement and dance. Pure euphoria, worries truly forgotten, only paying mind to the now.

Amongst the worries and fears that grip the gentle people of La Paz also lie excitement and animation, dance resurrecting the youthful spirits drowned out by everyday life. Dancing is not escapism, dancing is rejuvenation. The night brings this so desperately yearned-for feeling. In La Paz, the night is not your enemy but your friend.

Photos:Daisy Lucker/Adriana Murillo

A helping hand on every street corner of La Paz

Name: Rocio Grisel Melendres Condori

Age: 29

Gender: Female

Occupation: Bringing a ‘pedagogía del amor’ to the city of La Paz

‘I started on 7 February 2011. It was a Monday at exactly 3pm. I remember it very well,’ says Rocio Melendres about becoming a real life zebra-crossing for the city of La Paz.

Melendres became a zebrita for financial reasons. Like many others in the city, she was struggling to find work. ‘But I liked the project and I continued for many reasons,’ she claims, ‘not just for the money.’

The zebra programme is a place for individuals to develop themselves and gain experience whilst meeting and socialising with others. Focussed on the young people of La Paz and El Alto, the programme encourages individuals to become actors of social change in their surrounding communities.

Having volunteered as a zebra for more than six years now, Melendres is one of the most experienced zebras in the programme. Like many of the other participants, becoming a zebra had a strong impact on Melendres’ life: ‘My life before was very different,’ she explains. ‘As a citizen I didn’t add anything to the city. But once you are a zebra you see the city through different eyes. You fall in love with it. You want to help. [...] It helped me discover abilities I didn’t know I had and it helped me choose my career in education. Now I feel more involved with myself and my city,’ she says.

‘Before becoming a zebra I didn’t respect crossing lanes,’ Melendres continues. ‘I threw my trash on floor, I had bad habits. Now I put my trash in my pockets, in my bag. Many people come and find themselves through the programme. I was very shy, for example, but being a zebra helps you socialise with people and manage teams of volunteers. It helps you become a leader, and that’s what I’ve become.’

‘The Zebra programme is in your heart, you carry it with you. Ultimately what matters is your attitude.’

—Rocio Melendres

Although the zebras are famous for their costume and for helping you cross the city streets, they also bring happiness to many others in the city. They work all year round and train for two months during the winter. Apart from their role on the streets, the zebras also accompany senior citizens in chess games and storytelling activities and collaborate with local schools through a programme called Cultura Ciudadana, which addresses the recognition of individuals as citizens.

On the roads of La Paz, however, it’s not all fun and games. ‘Sometimes in the streets you find situations where you can’t do anything, you feel useless,’ Melendres tells me. One time, she saw a mother pulling an infant’s ear and yet there was nothing she could do. As a zebra, she did not have the authority to intervene. The only thing she could do was to try and make the baby smile to get him to stop crying. Additionally, some commuters find speaking to a mask easier than speaking to a real person and find time on the steer to tell Melendres about their problems. ‘One time a man came to up me and was crying as he told me his story. I was crying as well under my suit, but I had to cheer him up. I listened.’

When asked what the future holds for her, Melendres replies: ‘The truth is we are not going to stay here until we are old. The idea is to encourage more young people to find their path. It is important for them to know what they want to do with their lives.’ That is exactly what Melendres obtained through the programme. Now she is set on finishing her studies, building on her knowledge of the project that she has been coordinating for the last two years. ‘The programme is something that you hold in your heart, that you carry with you. Ultimately what matters is your attitude.’

Photo: Ana Diaz

The Aiquile International Charango Festival celebrates the cultural heritage of a musical companion present through hardships and happiness.

Buena onda is a good way to describe the people of the small central Bolivian city of Aiquile and their annual international charango festival, which celebrates and pays tribute to the cultural heritage of the small but powerfully iconic traditional Andean stringed instrument. Situated among the southern Quechua-speaking valleys of the diverse Cochabamba department, the ‘Capital of Charango’ is known for its dry climate, chicha, earthquakes, meteorites and, above all, its excellence in charango fabrication.

Combined with a familiar, friendly small-town feel, Aiquile’s charango festival greets us with a warm, relaxed vibe as we arrive in the blissfully beer-inviting mid-afternoon heat ahead of the closing night of the 34th annual celebration. Festivalgoers move around in trickles and spurts after the charango-playing competitions the night before and with the Gran Peña de las Peñas still to come in the evening.

The all-ages appeal of the charango is on show not only in the various age categories of the previous night’s competitions, but also with the youngsters who can be found enthusiastically strumming and picking the stringed instruments around town.

‘Music needs to be better supported in Bolivia,’ says paceño musician Rodolfo Ramírez Paredes. He speaks of the amazing ‘feel, technique and precision’ of some of these young charanguistas in attendance, some of whom nevertheless had difficulty in obtaining school permission to come to this year’s charango festival. Their predicament is evocative of the song ‘Niño Rebelde’, by the Quechuan group Norte de Potosí, in which a father asks his son what he wants to be when he is older and responds in repeated disbelief and protestation when the son maintains that he wants to be an artist, simply because he ‘likes it.’

Youngsters can be found enthusiastically strumming and picking the stringed instruments around town.

At the other end of the age spectrum, Walter Montero is exhibiting his ornately crafted charangos in the stalls next to the Manuel de Ugarte school stadium, where the festival’s main stage is set up. The former bandmate, friend and charango-making disciple of late virtuoso Bolivian charanguista and master craftsman Mauro Núñez, Montero is one of several master luthiers whose handiwork is on show for festivalgoers wishing to purchase a handmade instrument.

Visiting artisans and musicians also gather nearby, selling jewellery and accessories as well as sharing chicha, cerveza, coca and tunes, including rousing renditions of folkloric favourites ‘Ojos Azules’ and ‘Leño Verde.’ Among the music makers is Japanese-raised, La Paz-based Chupay Ch’akis charanguista Kenichi Kuwabara, who took first place in the international charango players competition the night before.

Later on in the evening, after the gentle lull of the afternoon has given way to the slowly simmering excitement of an impending barn dance, Kuwabara is duly given a barn-raising reception as he accepts his award on the main stage. Kuwabara, who initially started learning the charango from a maestro in his native Japan before moving to Bolivia, is ‘very happy’ with both prize and reception, as are aiquileños and Bolivians alike with the growing international presence at the festival, due to the uniting influence of the charango.

Then, as the last of the orange twilight finally surrenders to night and the bright stadium lights, I make the rounds to find out how festivalgoers feel about this year’s edition of the festival, with a key theme among locals being ‘pride.’ Pride for a celebration that recognises the importance of an instrument so well made and culturally ingrained in Aiquile over the years that – although Potosí is considered the birthplace of charango (due to indigenous potosinos creating the vihuela-inspired instrument during the Spanish conquest and the instrument’s vital place in the campesino culture of the region) – it is Aiquile that is known as the ‘Capital of Charango.’

Aiquileños have pride that their event is becoming an ever bigger, better and more culturally diverse festival in which to share and continue spreading all that encompasses the charango – and pride that this is a feelgood festival where people can come to listen to good music and pasarla bien.

‘The festival is well organised and getting better,’ says one aiquileño. ‘This year there are more people, I feel proud.’

‘It’s better than other years,’ says another. ‘There are more participants and more people.’

‘The festival is moving forward and we feel good about this. More visitors are welcome,’ says an aiquileño charango luthier, who also mentions that visitors to the charango festival are ‘very respectful.’

Aiquile is known as the ‘Capital of Charango.’

Finally, as the awards ceremony wraps up some time before midnight and the Gran Peña de las Peñas begins, we are treated to the spectacular force of Dalmiro Cuellar and his band: charango, guitars, violins, drum kit, an extravagantly played bombo, bass and chaqueño rancher spirit in full flow. An invigorating, fist-pumping rendition of the Tinku classic ‘Celia’ is the highlight of a fun and energetic set. Los Kory Huayras follow, and the warm night becomes blurry as crates of beer continue to be delivered to tables, kegs of chicha appear on the dance floor and revellers continue until 6am, when the police eventually kick them out.

Download

Download