In the West, Christmas is a fusion of pagan and Christian celebrations. In Bolivia, end-of-year festivities coincide with the arrival of the rainy season and the summer solstice, events that were vital for the agricultural pre-Columbian civilisations that ruled the continent. Today, the combination of Christian and indigenous traditions makes for a very special type of holiday, with a syncretism that manifests itself in parades and traditional indigenous dances performed in front of pesebres. One of our Bolivian Express elves, Charles Bladon, explores the intricacies of a Bolivian Christmas on page 22.

Indeed, an essential element of Bolivian culture and celebration is dancing. The holiday season is punctuated with parades, carnivals and opportunities to perform dances learned in school. But in this fastpaced world that we live in, different cultures and celebrations have become intertwined, their meanings sometimes lost and often hidden behind layers of newer traditions.

Traditional dances evolve and slowly start to lose their original essence. The Ballet de Bolivia attempts to preserve the primary meaning behind these traditions by combining classical ballet techniques with indigenous Bolivian dance. Fruzsina Gál interviews Jimmy Calla Montoya, the company’s founder and the driving force behind these efforts, on page 30.

In this issue of Bolivian Express, the last of the year, we want to celebrate Bolivia and its ancient, vibrant and evolving culture. And we are looking at it through the eyes of a new generation of Bolivian artists such as the pop singer Andoro in addition to culinary pioneers and entrepreneurs who are putting Bolivia in the forefront of their projects. Daisy Lucker takes a look at the new restaurant

Popular, which puts a modern and inspired twist on Bolivian cuisine in the historical centre of the city. And it’s quite a success, as the restaurant’s founders deliver on their inspired idea to provide contemporary Bolivian food made by Bolivians with Bolivian products. Another entrepreneur, hotel Atix co-founder Carlos Rodríguez, is also profiled in this issue about the arduous path he took to create a successful business, on page 36.

Traditions and celebrations in Bolivia are a patchwork, an aguayo tapestry that reflects the diversity and unity of the people of Latin America. One item that tells this story like no other, and which is central to Christmas celebrations in Bolivia, is the panetón, a sweet bread traditionally eaten around Christmas and paired with hot chocolate. A ubiquitous feature of Christmas in Bolivia, the panetón is actually a recent import from Peru (and originally brought from Europe by Italian immigrants at the turn of the 20th century). You can now find panetones made with such Bolivian ingredients such as coca and quinoa, and they are part of each and every Bolivian Christmas canastón.

By celebrating Bolivian-ness, we are also embracing the multitude of influences that accompanies it: the variety and uniqueness of this culture, the foreign and diverse influences that have helped shape the country since its formation and that are part of all of us – Bolivians, tourists, expats and the rest.

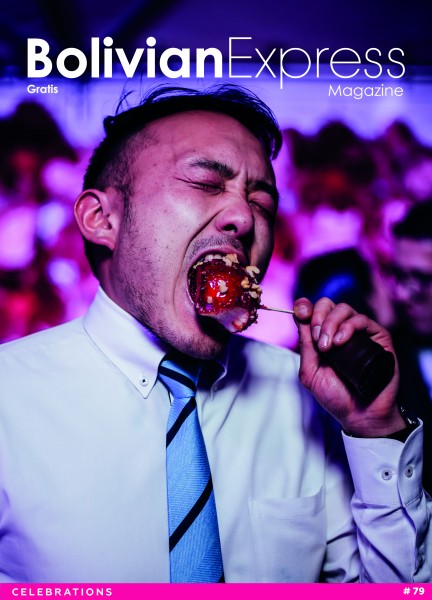

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

A new take on Bolivian hospitality

As we stand on the rooftop of the newly built, five-star Atix hotel, owner and co-founder Carlos Rodríguez poses for a picture as the sun shines in the background. Overlooking the beautiful sights of the upscale neighbourhood of Calacoto, Rodríguez explains the construction boom that has taken place here over the last ten years. ‘Things are always popping up here or there,’ he stresses, as he points at the nearest building in construction, which stands tall above the developing landscape. In less than a decade, Calacoto has transformed from a town dotted with small houses to a growing urban center brimming with commercial life. These new developments are creating a bold and modern new landscape.

Originally from Sucre, Rodríguez studied in La Paz for more than 14 years. He later ventured to Kansas City in the United States as an exchange student, before deciding to pursue a career in civil engineering. His position at Maxam, one of the world’s largest explosives manufacturers, took him worldwide, including of Kazakhstan, Spain and Panama. Little did his employer know, however, that the plush hotels he was put up in in became market research for the Rodríguez brothers’ future dream of opening up a luxury hotel. ‘I was working for five years with this company abroad, and by the third year we were contemplating having a hotel,’ Rodríguez tells me.

‘It all seemed to fall into place when my brother got married,’ explains Rodríguez. His brother’s new father-in-law was also interested in joining the pair to create the hotel. ‘We decided to go all in to buy land and then started talking with the banks and the architect who designed it.’

The Rodríguez brothers saw a gap in the market. From the beginning they were set on the theme of representing Bolivian materials and culture: ‘There is a lot of great hotels in Bolivia, but most of them are trying to copy something from outside of the country. They are trying to do a version of the Marriott or a Bolivian version of the Ritz. We saw that nobody was doing [what we are doing],’ says Rodríguez. Inspired by this Bolivian theme, they began building the hotel, choosing the designers and presenting their originality to create something new and different. Two years and eight months later, the plush hotel stands out from the rest of the highrise buildings in the area.

From the moment Rodríguez arrived at the plot of land where the hotel now stands, he decided to use the rock that originally covered La Paz during the 1920’s and 1930’s for its construction. Architect Stuart Narofsky flew in from New York to design the project. ‘He tried to put a lot of Bolivia into the building,’ Rodríguez says, ‘and the interior designer was the same. She was designing the furniture and then creating it here, except for the beds, which had to meet high international standards,’ he adds.

‘We saw that nobody was doing what we are doing.’

—Carlos Rodríguez, Co-Owner of Atix

But it wasn’t easy finding the right products to fill his hotel. ‘We struggled a lot,’ Rodríguez remembers. ‘Sometimes, we would find factories, but they would only produce their own models. Then we would find small producers who could not produce the quantities we needed.’ In the end, the construction involved four different carpenters. As Rodríguez shows us the different pieces that were created during this process, he points at the metal frame lamps hanging from the restaurant ceiling and at the tables made from tree trunks. ‘If you see the furniture and lamps,’ he explains, ‘all of them were made here. We are really proud of it.’

The theme of Bolivia is also present on the walls of the hotel. ‘We were thinking about having a lot of Bolivian artwork and thought about having one artist per floor. But that was really difficult because many of the artists didn’t understand what we wanted and had their own criteria,’ Rodríguez comments. However, when they came across Gastón Ugalde, known as the ‘the most important living Bolivian artist’ or the ‘Andy Warhol Andino’, everything fell into place. Ugalde presented a selection of photographs and paintings to the hotel, some of which date back to 1990’s and others which he produced during a two-month sabbatical around the natural sights of Bolivia. You can spot one of the photographs in the hotel’s dining area, featuring four small children holding the A, T, I and X on an abandoned truck in the famous Salar de Uyuni.

The rooftop of the hotel houses Ona Restaurant, which translates to ‘gift’ in Pukina and strives to serve food made for Bolivians, by Bolivians and with Bolivian products. ‘It is very hard,’ says Rodríguez, ‘because many of the products in Bolivia – including tomatoes, lemons, etc. – are imported. So you struggle.’

Success came early for Atix, as it joined the Design Hotels team in its first year of operations. Joining this selection of high quality worldwide hotels, which accepts only 4% of applications each year, allows Atix to reach a different, larger and more creative audience.

Photo: Ivan Rodríguez Petkovic

Exploring the quirks and staples of a Bolivian Christmas

Turkey, Christmas trees, fairy lights, snow and a warm fire: these are a few things that instantly come to my mind when the word Christmas is thrusted into conversation. Given my Western upbringing, my perception of Christmas is grounded in its setting (for me the blisteringly cold winter in England) and in the culture that has assimilated with this Christian holiday. But as Bolivia’s diverse range of Christmas traditions suggest, there is no such thing as a universal Christmas experience.

In our adventure of Christmas in Bolivia, we focus on the holiday’s very core, on the unique colonial traditions that have merged and evolved, giving form to local celebrations. In Bolivia, Christmas hasn’t merged into one suit and presents itself in various forms that almost mimic its linguistic diversity. From delectable dishes that bear no resemblance to European Christmas staples, to familiar sound of carol singers at the doors of fellow Christmas celebrants, Bolivia offers a host of peculiar and charming traditions that are worth exploring.

Box 1: Picana/Food

Food invariably plays a lead role in Christmases around the world, but whilst Turkey is customary in some European households, in Bolivia, the dish of choice is picana. Picana is a stew popularly eaten on Christmas Eve, made from a whole range of meats; including, beef, chicken, pork and lamb. There are numerous recipes that usually stem from grandparents, who in turn received them from their parents and grandparents. ‘We use beer, wine and vegetables,’ Patricia Zamora, a local paceña, explains, ‘but often people make it in a white broth, similar to chicken soup.’ Aside from the numerous ways one can prepare picana for the family, what remains constant is the time at which it is eaten. More often than not, dinner takes place close to midnight after a late evening service at the local church.

Box 2: Buñuelos

A few paceños have buñuelos instead at the stroke of midnight, saving the big meal for Christmas day itself. Buñuelos too plays a fundamental part in a Bolivian Christmas. Similar to a doughnut with a batter of cinnamon and flour, buñuelos are sprinkled with powdered sugar and usually served with hot chocolate. They make for small snacks during festive entertainments, but the local Christmas Market in La Paz supplements one’s need for a warm respite after a busy evening of present shopping.

Box 3: Christmas Market

Christmas markets have been around for decades in Bolivia. La Paz’s very own market off Avenida del Ejército in Parque Urbano is a Grinch’s nightmare supplying all the lights, candles, christmas trees, incense, miniature nativity sets (complete with miniature sandals for your miniature baby Jesus) and buñuelos one could possible want. But this Christmas oasis, which manages to obscure itself from the unfestive hustle and bustle of the Prado, offers more than goods, providing festive escapism and an opportunity to envelope yourself in the Christmas spirit. Some stall owners have even made a family tradition out of setting up camp on the winding market corridors.

Box 4: Nativity

In Bolivia, the adoration of Jesus on the day of his birth is very important, with feasts and dances that center around it. Many families across the country set up elaborate displays of the nativity scene, pouring their hearts and efforts into completing these pieces of art. Shoppers have no trouble finding figurines, scenic decorations and even clothes for the figures at the Christmas market. Whilst figurines are not unique to Bolivia, and can be seen across the world in many Catholic countries, what sets them apart are the different fashion elements they incorporate. Some Jesus figures are painted with a potosino or Andean motif, distinct in their hairstyles (often dark curl tufts) and the clothing sold with them, similar to the ponchos one can find on calle Sagarnaga, but a million times smaller.

Combining South American bombast and Christian tradition, this is a Christmas unlike no other.

Box 5: Music and Dance

No Bolivian Christmas is complete without festive music. Whilst in Europe families gather around a warm fire to sing soft traditional carols (or more modern tunes with a pop influence), Bolivian Christmas music has an upbeat, jovial feel. Adding to the atmosphere of animated jingles, Bolivians dance to the songs, skipping, frolicing and twirling. Children, parents and grandparents follow suit, all for the baby Jesus and the nativity scenes that embellish front rooms.

Bolivian Christmas is nothing short of a spectacle. Combining South American bombast and Christian tradition, this is a Christmas unlike no other. Although no blanket statement can be made for Christmas celebrations in the country, a summarisation of the food, places and traditions is all one can make to capture the festivities that Bolivia forges.

Photo: Claudia Prudencio

Transgressing the boundaries of performance in Bolivia

Andoro is no musician alone. This was made clear the moment he stepped through the front door of the coffee shop and greeted me. Andean poncho, duffle coat and denim shirt in toe, it was also clear that Andoro takes his fashion seriously. Whilst he released a five-track album this year, entitled Inmortal, his exploits haven’t been grounded in music alone. Andoro uses his concerts to explore other mediums as well, such as visuals and fashion. He is an artist that thrives on the multifaceted nature of art, choosing both his love of fashion and music and never settling for one.

Yet there was no start for Andoro. For as long as he can remember he has always been interested in music, as if it were intrinsic to his being. ‘My mother used to tell me that when I was a baby I would react to music,’ Andoro explains, ‘It was in my DNA. My whole world was built by sound and music. Every Christmas I’d ask for something that would make noise.’ Andoro, a name he chose for himself, learned to play the harmonica before he could even pipe a word. His big break wouldn’t materialise until he deviated from his studies in social communication and pursued his passion. Surrounding himself with like-minded artists, such as Vero Pérez from the jazz-pop band Efecto Mandarina, he eventually gained the confidence to take the stage.

Inspiration and support from artists, friends and partners in the artistic world helped form Andoro as we know him today. His friendship with Joaquin Sánchez (an internationally renowned visual artist) was vital in his experimentation with live visuals for performances. Sánchez allegedly gave him the piece of advice by which he seems to live by today. ‘I told him I wanted to try to make it into the music business,’ Andoro remembers, ‘but that if it didn’t work out I would try fashion instead. Then he told me: “You don’t have to choose.”

Whilst he released a five-track album this year, entitled Inmortal, his exploits haven’t been grounded in music alone.

His willingness to break the boundaries between the arts has bled through in his music. He says himself that his album is ‘pop and electronic with experimental elements.’ Incorporating further Andean influences, he states: ‘From the preparation of meals to the offerings you make to Pachamama, everything is ritualistic in Bolivia. I want that to reflect in my music, which is why my songs sound like rituals.’ Inmortal provides a soundtrack that Andoro feels is like a musical journey. Its diversity, from intense ritualistic spoken word to the warm soft comforts of his duets with Vero Pérez, is a key strength of his album and is metaphorical of the project itself.

As a result, his live performances are spectacles in which he uses what he has learnt from various artists. When I ask him about his concerts, he simply replies: ‘They aren’t concerts, they are more of an experience.’ This is plain to see in the elements that factor into his performances, as Andoro tries to overwhelm the senses, making his shows truly unique.

‘They aren’t concerts, they are more of an experience.’

—Andoro

‘We have a lot of point of views working on one project,’ Andoro says. ‘It is a collaborative community of artists, sculptors, photographers and cinematographers. This is the strength of our endeavour.’ For Andoro, this is only the beginning. In the future he hopes to host various pop-up events, using spaces such as cinemas for visual events, and hopes to get out on the streets more. ‘My music is inside a bubble now,’ he says, ‘this is good because it’s safe in the bubble and there aren’t many people punching at it, but I want my music out on the streets.’

Surely enough, Andoro is only emerging as an artist. If this bubble of protection eventually pops, then the people of Bolivia will hopefully come to celebrate the diversity of his project, which is a fitting match for the times Bolivia lives in today.

Download

Download