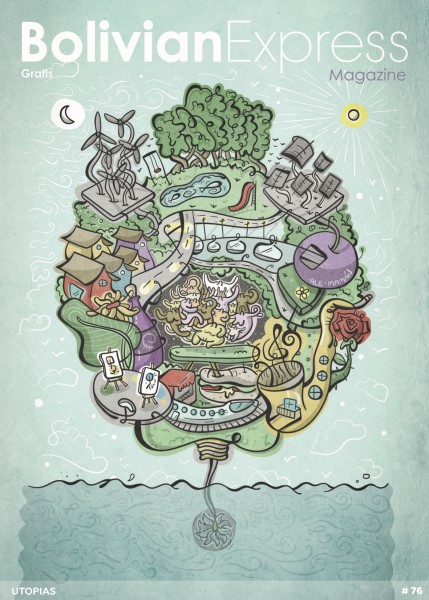

Antonio de León Pinelo, a 17th-century Spanish-colonial historian, placed the ‘Earthly Heaven’ in the heart of the Amazon jungle and imagined Noah’s Ark drifting down the Amazon River. The legends of El Dorado, the Fountain of Youth and the biblical return to paradise forged fragments of Latin American stories and identities. These utopias were based on the dreams and desires of the Spanish conquistadores, who saw in the ‘untouched’ lands of the Americas an opportunity to create perfect communities.

To begin to understand Bolivia, one has to see it from an outside perspective, to look at it through the myths and stereotypes that have shaped the idea of the country from abroad. The myths and the idealised versions of Bolivia and its people are intrinsically linked with a historical reality and the way in which the country has been formed. The remains of the colonial past are not only found in the social, economic and political spheres of modern Bolivia – they are also a part of how its people dream, love and identify themselves.

There are many different kinds of utopias one can find in Bolivia: vestiges of the dreams of the Spanish colonisers; our hopes for the future; and our (re)interpretations of the past, in the way history is reinvented to fit the present. As just one example of this utopian tendency, we can see how the 1952 Bolivian Revolution started a process of decolonisation in order to remove domineering political and racial structures and replace them with indigenous systems and indigenous history.

In this attempt to understand these different utopias, Catriona Fraser travelled to the Imperial Villa, now known as Potosí. By digging up bones buried deep down in the colonial city’s crypts and catacombs, potosinos are coming to terms with a painful past, facing and embracing all facets of their history.

Sixty years ago and 17,000 kilometres away, Japanese settlers were sold tales of a new promised land situated somewhere near Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in eastern Bolivia. Nick Ferris visited the colonies of San Juan and Okinawa to see the communities these settlers created. Meanwhile, Catriona Fraser continued her journey to María Auxiliadora, near Cochabamba, a woman-led community that used to represent a safe haven for women escaping domestic violence, but in which neighbours now find themselves cleaved apart.

And there are our own personal utopias. Our writers share theirs: Robert Noyes finds perfection in the shape of a jumper found in El Alto’s massive market; Fabian Zapata imagines a Bolivia in which we send hand-written letters to each other; Julio C. Salguero Rodas photographs the faces of Tiwanaku, wondering who they were and what they dreamt about.

Together we ponder the possibility of travelling from Peru to Brazil by train while respecting the diversity of the continent. And, finally, we contemplate how the Bolivian cosmovisión is rooted in the concept of Suma Qamaña, a notion in which it is possible to ‘live well’ in harmony not only with other people but with nature too. Let’s hope that, for the future of Bolivia and Latin America, this idea doesn’t turn into just another lost utopia.

Photo: Nick Ferris

Seeking utopia halfway across the world

Deep in the breadbasket country of eastern Bolivia, around the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, exists something rather remarkable. In the centre of a broad and dusty town lies a low pagoda-like structure fronted by a large wooden gate and dark-green walls, and topped by golden Japanese characters. ‘That building is a kominka, the traditional house of Okinawa,’ says Nobutoshin Sato, the secretary general of the Bolivian-Japanese Nikkei association and my guide to the two Bolivian-Japanese colonies of Okinawa and San Juan de Yapacani. This particular structure in Okinawa, quintessentially Japanese but nevertheless happily lying along the main road of a typically Bolivian town, represents the symbiotic existence Japanese settlers have come to find in eastern Bolivia.

Immigrants first came from Japan to Bolivia in the late 19th century to take advantage of the rubber boom in the departments of Pando and Beni. Those enterprising people came on their own to a wild and undeveloped country. Their descendants have long since been absorbed into the wider Bolivian population, for the most part leaving no trace of their heritage but their surnames.

The Japanese in the colonies of Okinawa and San Juan came in the aftermath of World War Two, escaping their defeated homeland alongside hundreds of thousands of other emigrants who sought a new life South America. The government of Bolivia granted 50 hectares of land to Japanese families in return for their manpower. Okinawa was named after the American-occupied Japanese island from which the settlers came, while San Juan was named after the land in which they settled. In the first ten years of immigration beginning in the early 1950s, 3,200 Japanese people settled in Okinawa and 1,600 in San Juan. Today, around 800 live in each. Both colonies have found great wealth through their agricultural endeavours: Okinawa is famed for its production of grains and cash crops like rice, wheat and soya; while the smaller colony of San Juan produces more specialist items like citrus fruits, macadamia nuts and eggs – currently 700,000 eggs a day.

Latin America has historically been perceived as a land of exoticism and utopia, a new world for migrants to begin a fresh and idealised existence. Both towns have a strange sense of a closed, idealised community inherent to the endeavour of founding a colony. They have Japanese-run hospitals and schools, Japanese graveyards and restaurants, and access to Japanese TV. Yet a visit to San Juan’s museum with Masayuki Hibino, the 78-year-old president of the Bolivian-Japanese Nikkei association, revealed the settlement had a far from ideal beginning.

Hibino is an Issei, or first-generation immigrant, who took the two-month ferry journey to South America in 1957, aged 18. ‘My father was a specialist at selling and repairing cameras but his business was failing,’ he tells me. ‘There was only a 30% employment rate, everyone was struggling to get by.’ Faced with no apparent future, his family was drawn to Japanese state propaganda offering a new life in Bolivia. ‘My father had two houses in the city,’ Hibino says. ‘He sold them for ¥600,000 [or $800 per house] in order to pay for transport to South America. We were promised land, access to a main road, a school and other amenities.’

The reality of their arrival, says Hibino, was very different. ‘We arrived in Corumba [a city in southern Brazil] and were sent across South America in trains designed for cattle. When we reached the land designated for us,’ he recalls, ‘there was nothing there, only jungle. We had to transport all our crops through the jungle with horses. We built the first school by hand with hojas de motacú,’ he says, ‘it was a choza.’

Returning to Japan was also not an option.‘The boats were coming from Japan,’ Hibino explains, ‘we weren’t going the other way. Plus, if we wanted to go back we would need to pay $3,000 each. At that point, we were only making $14 a month.’

The situation was the same, if not worse, in Okinawa, where the first settlement was met with an epidemic of a variant of the hantavirus in which 15 settlers died. There were times of drought, times of flooding. They moved the settlement twice before settling for good.

‘We were promised land, access to a main road, a school and other amenities.’

–Masayuki Hibino

It was very affecting to hear the elderly Hibino’s story, to have him eagerly show me photos of his family at the port in Kobe prior to their departure and of his community’s struggles in the early days. He proudly showed the kimonos, a samurai sword and other artifacts the settlers had brought with them. He even demonstrated how the old, pedal-operated picadora de arroz worked. Hibino, who has seen the rise of his community, was understandably nostalgic about times past.

Meeting Satoshi Higa Taira, the secretary of the Japanese organisation in Okinawa, was a different story. Higa is a Nisei, or second-generation immigrant. He has a Bolivian wife, speaks fluent Spanish with a camba accent and identifies more as Bolivian than Japanese. Perhaps it is among this more settled generation that the Bolivian-Japanese utopia has been found.

‘We are born here, we only know this way of life,’ he tells me. ‘We see the competitiveness of countries like the USA and Japan. There is so much pressure there and everything is the same.’ Higa is among many Japanese known as the Dekasegi (‘the returned’), who went back to Japan in the 1980s to take advantage of the booming bubble economy. He then came back to Bolivia, preferring the more relaxed and less repetitive Bolivian way of life, to a modern, fast-paced Japan, where returning emigrants are not always welcome.

Unlike the early days that Hibino described, current-day Bolivian-Japanese have more land, mechanised farming techniques and more money and are at the forefront of an ever-growing consumer market that has opened across the country. ‘There is a stability now,’ says Higa.

The Japanese colonists have also forged a hybrid sense of identity, taking advantage of favoured aspects of Japanese and Bolivian cultures. Local shops, for example, sell Japanese products that are unavailable elsewhere. According to one Nisei in San Juan, when the younger generations come home to the colonies from university in Santa Cruz, ‘they eat, eat and eat! Our Japanese food is something that will never change.’

Higa also stresses the importance of a Japanese-style education. ‘We want our children to have the same education and attitude as they would have in Japan,’ he says. ‘This attitude is what is most important.’ The hard-working, resourceful ‘attitude’ of the Japanese people has of course made them successful all around the world. Yet it was also evident, in the way I travelled around with Nobutoshin Sato, jumping from minibus to minibus and sharing street food along the way, that for modern Bolivian-Japanese this ‘attitude’ translates into a thorough engagement with everyday Bolivian life and society.

The modern colonists are also very generous with their cultural heritage. Locals are invited to all events at the cultural centres. ‘We really want to include everyone in our traditions and activities,’ insists Higa. The Japanese schools welcome Bolivian and Japanese children, teaching in Spanish in the morning and Japanese in the afternoon.

So, is this utopia? A utopia is a place defined as the pinnacle of aspirations and dreams. It seems human nature dictates that such a state of entire fulfillment will never truly exist for our species. Just like the dream-like propaganda that Hibino’s family fell for 60 years ago in Japan, the reality of life in the colonies will never be utopian. The sense of contentment evident in the Nisei and their descendents masks the incredible toil and effort that they invest in their communities to make them successful. And with success comes a handful of other problems, like Bolivian farmers migrating to the area to sell products under the name of ‘Okinawa’ or ‘San Juan’ and take advantage of their reputation for quality.

The Japanese colonists have forged a hybrid sense of identity, taking advantage of favoured aspects of Japanese and Bolivian cultures.

The prosperity of the colonies cannot be taken for granted. But as Higa says, if the modern residents of San Juan and Okinawa sustain the qualities and attitudes of their founders, they will surely continue to prosper in the years to come.

Photo: Julio C. Salguero Rodas

More than a millennium after its demise, Tiwanaku has become a Unesco world heritage site.

I ask our guide Hugo Tarqui Blanco what is the one thing that made Tiwanaku so successful:

‘It’s the extraordinary construction. The precision, the great architects, hydraulics engineers, metal workers behind it. The precision is tremendous, this is why for some time, it was said that probably they could make the stones’.

He tells me, ‘Architecturally, they based it not only on what we call the Andean cosmovisión, but also on the three levels: Sky, Earth and Underworld.’

The semi-underground temple, the Kalasasaya temple, the pyramid of Akapana and Pumapunku are four of the seven most important structures. I ask Hugo why number seven is important in understanding Tiwanaku. He responds, ‘The number seven is important, because it is based on the four elements which are: Air (The Condor), Earth (The Puma), Fire (The Llama) and Water (The Fish).’

It’s these four elements fused with the three Sky, Earth and Underworld levels which gives us the number seven. This is reflected in their architecture: seven structures with seven platforms, and seven steps in each stair.

As I leave, I look on the ground to see the many footprints of people who come every day to visit the site. I can’t help but think that another century may pass before we fully understand and discover in its entirety what made Tiwanaku so exceptional. A wait all the more exciting.

Photos: Catriona Fraser and Nick Ferris

A look at the past to serve the future

It is the 1990s, and the roof of San Agustín church groans a final breath of life before surrendering to the mould of time and collapsing into the floor beneath. Dust dances in the speckled light of the hall, before slowly settling to reveal something that has been lying in a secret silence under this old church for more than 300 years. It is something that susurrates with a promise of skeletons, of legends, of skulls: catacombs – something that, ironically, promises revival.

When asked about Potosí’s past, many see an image of utopia. Like the town itself, the public perception of Potosí is caught in the shadow of Cerro Rico, the mountain that raised Potosí on a bed of silver and made it one of the largest and richest cities in the world by the end of the 16th century. However, when one delves into the darker corners of the colonial era, it is unclear whether Potosí’s past can truly be given the title of utopia. It is not only the evanescent nature of the silver boom that hints at the negative-utopia of Potosí’s history, but also the murmurs of death, of murder and of slavery, which mutter beneath the glittering history of this once opulent city. The colonised era of Potosí is scarred by the horrendous working conditions of the mines. It is estimated that between 1545 and 1825, around 8 million lives were lost at the hand of colonial greed, mainly the lives of African slaves and indigenous labourers.

Yet it is difficult for the external viewer not to see Potosí as an anachronistic echo, and avoid being impressed by the shining, albeit ephemeral, glory of its history. By turning our gaze to the past, however, we risk losing sight of a present expanding city. With the discovery and planned recuperation of catacombs beneath Potosí’s streets, a new utopia has begun to rear its head.

Architect Daniel Sandoval, who is the Director of Patrimonio Honorable Gobierno Autónomo Municipal de Potosí and leader of the catacomb restoration project, tells me the project began at the start of last year. At present, it is in the process of recuperating the network of catacombs that runs underneath the city, with the aim of opening it to the public. The enterprise is part of a wider scheme that involves the convalescence of five World Heritage Sites around Potosí. The goal is to make these sites accessible to the public, with the creation of cycle lanes, souvenir shops, a transport system and safety measures to suit. Potosí is a town of dreams and aspirations and the catacombs are no exception. By excavating and recuperating these networks of mystery, it is hoped that tourism will bring money back to this area by showing a different side of Potosí.

Potosí is a town of dreams and aspirations and the catacombs are no exception.

Like the rest of the city, the San Agustín church vibrates with a promise of legends and history, of tales and mystery. Most of the bones found underneath the church floor were of indigenous descent – men, women and children – and were marked by a single hole pierced through the skull. While work is still being carried out to understand exactly who these people were and how they died, one hypothesis is that they were sentenced to death, or perhaps underwent the procedure of trephining, a process in which a hole is drilled into the skull to remove evil spirits from the body. Now the skulls look straight back at you, the hollow sockets of the eyes daring you, provoking you, asking you to find out more. As Sandoval stated when I talked to him on my visit, ‘the idea is to preserve the catacombs and show them the way we found them.’

The catacombs are not restricted to San Agustín, but they extend beneath the feet of the present city. One of the most ambitious parts of the project, is the recuperation of catacombs that run below the Cathedral and stretch to a school in the centre of Potosí. The resurrection of the San Agustín catacombs alone will cost around two million dollars, since the walls need to be reinforced and glass paneling needs to be put in place. As Sandoval explains, the project awaits funding before it can open to the public. ‘We presented it to different entities: The Ministry of Culture, the European Union, the Spanish Cooperation (ESIP), but we still haven’t heard a reply,’ he says.

Thus, while the past utopia of Potosí echoes through its history books, and the present reveals itself from beneath the city floor, it is from the outside that the future of this project can hope to continue. There is a certain irony in that the city that once benefited foreign colonisers with its silver, now needs external funding to progress. For now, the next rise of Potosí remains an aspiration; yet it is an aspiration that is becoming increasingly real for the people of the town, as legends and tales solidify into reality. The catacomb project poses a possibility for Potosí to look at its past while serving its future. It presents an opportunity for the city to move forward from the darkness of its colonised era and convey its own pride in the unique culture of this growing, idiosyncratic city.

The city that benefited colonisers with its silver, now needs external funding to progress.

Download

Download