Antonio de León Pinelo, a 17th-century Spanish-colonial historian, placed the ‘Earthly Heaven’ in the heart of the Amazon jungle and imagined Noah’s Ark drifting down the Amazon River. The legends of El Dorado, the Fountain of Youth and the biblical return to paradise forged fragments of Latin American stories and identities. These utopias were based on the dreams and desires of the Spanish conquistadores, who saw in the ‘untouched’ lands of the Americas an opportunity to create perfect communities.

To begin to understand Bolivia, one has to see it from an outside perspective, to look at it through the myths and stereotypes that have shaped the idea of the country from abroad. The myths and the idealised versions of Bolivia and its people are intrinsically linked with a historical reality and the way in which the country has been formed. The remains of the colonial past are not only found in the social, economic and political spheres of modern Bolivia – they are also a part of how its people dream, love and identify themselves.

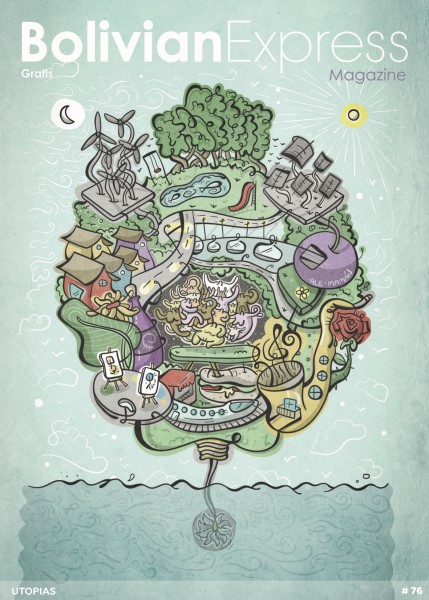

There are many different kinds of utopias one can find in Bolivia: vestiges of the dreams of the Spanish colonisers; our hopes for the future; and our (re)interpretations of the past, in the way history is reinvented to fit the present. As just one example of this utopian tendency, we can see how the 1952 Bolivian Revolution started a process of decolonisation in order to remove domineering political and racial structures and replace them with indigenous systems and indigenous history.

In this attempt to understand these different utopias, Catriona Fraser travelled to the Imperial Villa, now known as Potosí. By digging up bones buried deep down in the colonial city’s crypts and catacombs, potosinos are coming to terms with a painful past, facing and embracing all facets of their history.

Sixty years ago and 17,000 kilometres away, Japanese settlers were sold tales of a new promised land situated somewhere near Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in eastern Bolivia. Nick Ferris visited the colonies of San Juan and Okinawa to see the communities these settlers created. Meanwhile, Catriona Fraser continued her journey to María Auxiliadora, near Cochabamba, a woman-led community that used to represent a safe haven for women escaping domestic violence, but in which neighbours now find themselves cleaved apart.

And there are our own personal utopias. Our writers share theirs: Robert Noyes finds perfection in the shape of a jumper found in El Alto’s massive market; Fabian Zapata imagines a Bolivia in which we send hand-written letters to each other; Julio C. Salguero Rodas photographs the faces of Tiwanaku, wondering who they were and what they dreamt about.

Together we ponder the possibility of travelling from Peru to Brazil by train while respecting the diversity of the continent. And, finally, we contemplate how the Bolivian cosmovisión is rooted in the concept of Suma Qamaña, a notion in which it is possible to ‘live well’ in harmony not only with other people but with nature too. Let’s hope that, for the future of Bolivia and Latin America, this idea doesn’t turn into just another lost utopia.

Photo: Iván Rodríguez

As South American railways fall into disuse and disrepair, Bolivia looks to expand its network.

Back in 2011, I decided I wanted to know my country, Bolivia, better. I begun my journey by embarking on an Expreso del Sur train going from Oruro to Uyuni. I was 21 at the time, and this experience meant something special to me because of one fundamental element: I had never taken a train before. Furthermore, until recently I had never realised the historical importance behind these locomotives and carriages and their contribution to the Bolivian national economy. Not only were trains instrumental in carrying silver and other riches from the mines to the Pacific ports, they used to be the preferred method of transportation, connecting Bolivia to the rest of South America. But today, railways in South America have largely disappeared. But Bolivia, with 1,834 kilometres of track, has the longest network on the continent.

As I remember this journey, I also realise that my generation and the ones that follow don’t have any knowledge about these railways and what they represent for Bolivia. They were like living veins traversing the country’s five departments, and they are still used to this day to transport a large amount of the country’s external trade to its neighbours. Maichol Piñango, inter-institutional manager of Ferroviaria Andina S.A. (FCA) tells me, ‘In 2016, more than 1,300,000 tonnes of cargo were carried across the country.’ And, he adds, ‘in the communities of western Bolivia, a high number of passengers are still taking the train.’

In the current economic and political context, Piñango also thinks that FCA, considering all its technical capabilities and desire to invest in Bolivia, could play a major role in the Bioceanic Train line in which Bolivia is involved. The Bioceanic Train is a mega-project that will connect the port of Ilo in Peru, cross the whole of Bolivia’s territory via El Alto, La Paz and Puerto Suárez, and terminate in Corumbá, Brazil. From Corumbá, there will be a connection to Santos, a large railway port near São Paulo.

The Bioceanic Train is a mega-project that will connect the port of Ilo in Peru, cross the whole of Bolivia’s territory via El Alto, La Paz and Puerto Suárez, and terminate in Corumbá, Brazil.

With this project, it becomes tempting to envision a second railroad age in South America. This could become a reality in a near future since the Bioceanic Train involves the governments of Peru, Brazil and Bolivia signing a tripartite treaty. This would give Bolivia a very strong negotiating position. For the first time in a long time, Bolivia would gain (indirect) access to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and would become the heart of the continent’s commercial and touristic networks. This central position upon which the other South American economies would depend could play a huge role for Bolivia, both economically and politically.

Another one of FCA’s priorities is tourism. Piñango explains that one of his company’s priorities is to develop an online presence on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube while also maintaining a website in Spanish and English where tourists and travelers can directly purchase train tickets. The marketing strategies the company is currently implementing promote popular destinations like Lake Titicaca, Tiwanaku and Salar of Uyuni. But FCA also wants to the raise the profile of lesser-known places like Tupiza, where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid met their end; Guaqui and its locomotives museum; and Machacamarca, near Oruro. By opening up these new routes, FCA wants to give more options to the traveller who wants to learn more about Bolivia.

FCA is also focusing on developing strategic alliances with the Bolivian Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Last year, for instance, FCA represented Bolivia at the International Tourism Fair of Latin America in Buenos Aires. The company also works closely with local tourism agencies. Because of these collaborations, FCA has become one of Bolivia’s major ambassadors abroad by promoting its projects and offering alternative South American travel itineraries. Instead of buses, travellers will be able to travel along the Inca Trail by train. They will ride the rails from Cuzco in Peru to Argentina, with stops along the way in La Paz, Uyuni, Potosí and Villazón.

Piñango says that the majority of foreigners traveling in Bolivia by train are from Argentina. But French, American, Korean and Chinese tourists can also be frequently seen travelling by train. Piñango hopes for the train to become part of the Bolivian culture, for more tourists to experience this way of travelling, something he views as much more ‘emotional’ than travelling by bus. ‘It’s also more comfortable,’ he adds. ‘In our Expreso del Sur line, we have a restaurant coach where you can have lunch and dinner.’ Piñango also counts on charter trains in which groups up to 80 people can rent carriages.

It’s a much more ‘emotional’ way of travelling than by bus.

When I first took the train to Uyuni, I had no idea of this potential, and talking with Piñango made me realise and understand why travelling in train is so special. That journey I took was indubitably one of the best of my life, not only because of the breathtaking scenery, but also due to the train itself. The experience brought back feelings of nostalgia and happiness, emotions I didn’t expect to encounter at that time. Maybe it was because it was my first time travelling in train, or maybe it was the histories, memories, anecdotes and characters of my country that were resonating through that train.

By developing freight and passenger services, FCA may be about to revive one of Bolivia’s most important mode of transportation: the train.

For more information visit: www.fca.com.bo

Photos: Fabián Zapata

As electronic communications become the norm, an old institution gathers dust

One of the most important buildings in the city of La Paz is the central post office: a daunting 20-storey tower and symbol of Bolivia’s economic boom. The offices within the building are filled with demotivated officials whose salaries are paid late and who receive no social benefits, a group of people whose ultimate concern is that letters reach their intended destination.

The corridors are vast and empty, decorated in typical 1970s style: walls lined with wood, yellow candlesticks and leather seats. You can sense a certain melancholic atmosphere in this building where every family in La Paz once had their own letterbox, where they could retrieve their post and parcels. Good news and bad news, love letters, business opportunities, prayers and threats all came through these letterboxes.

At the end of these bleak corridors is an old lady who accumulates blue sacks full of packages and overdue letters that are less likely to reach their intended recipient. Letters lie on the floor and boxes have collapsed in on themselves. They take all the time in the world. Yet the reality is that we remain dependent on this institution. Legal papers and packages cannot be sent via Internet. So much depends on the mood of these few officials.

Download

Download