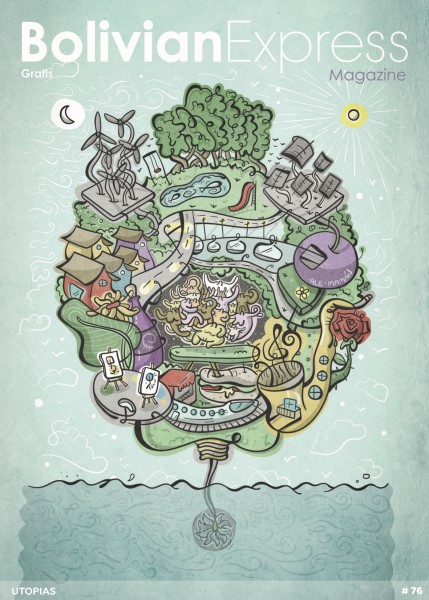

Antonio de León Pinelo, a 17th-century Spanish-colonial historian, placed the ‘Earthly Heaven’ in the heart of the Amazon jungle and imagined Noah’s Ark drifting down the Amazon River. The legends of El Dorado, the Fountain of Youth and the biblical return to paradise forged fragments of Latin American stories and identities. These utopias were based on the dreams and desires of the Spanish conquistadores, who saw in the ‘untouched’ lands of the Americas an opportunity to create perfect communities.

To begin to understand Bolivia, one has to see it from an outside perspective, to look at it through the myths and stereotypes that have shaped the idea of the country from abroad. The myths and the idealised versions of Bolivia and its people are intrinsically linked with a historical reality and the way in which the country has been formed. The remains of the colonial past are not only found in the social, economic and political spheres of modern Bolivia – they are also a part of how its people dream, love and identify themselves.

There are many different kinds of utopias one can find in Bolivia: vestiges of the dreams of the Spanish colonisers; our hopes for the future; and our (re)interpretations of the past, in the way history is reinvented to fit the present. As just one example of this utopian tendency, we can see how the 1952 Bolivian Revolution started a process of decolonisation in order to remove domineering political and racial structures and replace them with indigenous systems and indigenous history.

In this attempt to understand these different utopias, Catriona Fraser travelled to the Imperial Villa, now known as Potosí. By digging up bones buried deep down in the colonial city’s crypts and catacombs, potosinos are coming to terms with a painful past, facing and embracing all facets of their history.

Sixty years ago and 17,000 kilometres away, Japanese settlers were sold tales of a new promised land situated somewhere near Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in eastern Bolivia. Nick Ferris visited the colonies of San Juan and Okinawa to see the communities these settlers created. Meanwhile, Catriona Fraser continued her journey to María Auxiliadora, near Cochabamba, a woman-led community that used to represent a safe haven for women escaping domestic violence, but in which neighbours now find themselves cleaved apart.

And there are our own personal utopias. Our writers share theirs: Robert Noyes finds perfection in the shape of a jumper found in El Alto’s massive market; Fabian Zapata imagines a Bolivia in which we send hand-written letters to each other; Julio C. Salguero Rodas photographs the faces of Tiwanaku, wondering who they were and what they dreamt about.

Together we ponder the possibility of travelling from Peru to Brazil by train while respecting the diversity of the continent. And, finally, we contemplate how the Bolivian cosmovisión is rooted in the concept of Suma Qamaña, a notion in which it is possible to ‘live well’ in harmony not only with other people but with nature too. Let’s hope that, for the future of Bolivia and Latin America, this idea doesn’t turn into just another lost utopia.

Photo: Bx Crew

A game-changing law that endangers the park

Back in 2011, we printed a special edition themed around the TIPNIS, which stands for the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory. We looked into the culture of protest in Bolivia, and tried to understand what this fight meant for the country’s future and how the TIPNIS became a symbol of identity for many Bolivians. Following a 40-day march led by indigenous organisations, on 24 October 2011 the government passed a law declaring the intangibility of TIPNIS. We are now revisiting the topic in light of a recent development. On 13 August 2017, the government passed Law 969, which cancels Law 180 and with it, the ‘intangibility’ of the national park.

Six years ago, swathes of marching feet swarmed into La Paz in a wave of protest, after walking over the soil that covers most of Bolivia: from the harsh altiplano of the highlands, to the damp earth of the lowlands. The march emerged in response to the government’s decision to build a highway through TIPNIS, home to almost 70 different indigenous communities and to one of the highest densities of biodiversity in the world.

Back then, TIPNIS was used as a springboard for multiple converging, contrasting and often colliding objectives. The debate augmented into something greater than extractivism against environmentalism, or infrastructure against indigenous rights. It snowballed into the culture of protest inherent in Bolivian society, a culture that uses strikes and marches as a form of democracy.

TIPNIS emerged to become a question of identity, of self-determination, of the very essence of citizenship in a nation that claims to embody a multicultural, plurinational ethos. Although president Evo Morales argued he was ‘working for the dignity of all’, this was seen to dissolve into ‘working for the dignity of some’. Eventually, facing both national and international pressure, the government withdrew its plans. This year, the plans have been officially revived, and the construction of the road is expected to continue.

So, what has changed?

Pablo Villegas, investigator at Centro de Documentación e Información Bolivia, is not surprised by the latest developments. He sees it as a logical step of the ‘progressive extractivism’ policy articulated by the government. According to Villegas, the recent reversal regarding TIPNIS, is in line with the Coca law of 13 March 2017, which increased the cultivation area of the leaf from 12,000 to 22,ooo hectares. For better or for worse, Villegas sees a larger pattern and a planned policy to integrate Bolivia with the South American continent through the extraction of the country’s natural resources.

‘There can’t be an intangible territory...We can’t live from subsistence anymore.’

–Pedro Vare, President of CIDOB

The road, which will link Villa Tunari in the department of Cochabamba to San Ignacio de Moxos in the Beni, is meant to support the development of the area. Indigenous communities living in the park will benefit from the construction of schools and hospitals and will gain access to basic services. Some indigenous leaders argue that the notion of ‘intangibility’ has become more of a barrier to the economic and social growth of indigenous people, than a concept that protects them. Pedro Vare, the recently elected president of CIDOB (Confederación de Pueblos Indígenas de Bolivia), denies that the fight was ever about making the park intangible. ‘There can’t be an intangible territory,’ he says. ‘We are human beings, we have fundamental rights. We have a right to develop in a productive way. We can’t live from subsistence anymore.’

His call for development and his acceptance of the road ring hollow, but show how much things have changed in only six years. Back in 2011, Vare and CIDOB were at the forefront of the TIPNIS march. According to Norka Paz, an environmental activist, their change in position is the result of the ‘progressive weakening of indigenous organizations that has occurred due to oppression, repression and monetary incentives.’

The reality is that several stakeholders would benefit from the TIPNIS road and the extraction of the park’s resources. The road would benefit the cocaleros in Polygon 7, an area in the south of TIPNIS that was delimited in 1992, when colonisers from the highlands flooded the region. In their search for work, these migrants started planting coca, leading to the deforestation of 60% of the area. The growth of the crop raises fears regarding narco trafficking in the park. Between 2015 and 2016, the cultivation of illegal coca increased by 150% in Bolivia, according to the UN office on Drugs and Crime.

Another suggested motive for the road’s construction is the discovery of hydrocarbon banks in the TIPNIS. Since Morales’ election, gas and oil contracts have been renegotiated through nationalisation and foreign investments. According to the Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Laboral y Agrario, based in La Paz, one third of the park has been marked for natural gas extraction. Ganaderos, madereros, soyeros would also gain easier access to the park and could start cutting, planting and colonising the park.

The planting of soy crops in particular, could prove advantageous to Brazilian interests. With a road through Bolivia, linking the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, Brazilian soy planters could access Asian markets significantly faster and cheaper. ‘Instead of the 26 to 30 days it currently takes them to reach Asia, through Bolivia it would take 5 days,’ says Pablo Villegas, while pointing at the shortcut on a map.

Fifty percent of the communities in the park are too far from the road to benefit from it.

Even if Bolivia has a lot to gain economically and politically from integrating within the continent, it is not clear how the incursion into the park will benefit local indigenous populations. After laying a large map of the TIPNIS on the table in front of us, Villegas and Norka Paz sketch the planned construction route with a marker. As Villegas points out 50% of the communities in the area are too far from the road to benefit from it. ‘For electricity, you need cables,’ he says, ‘not a road.’

More than the construction of the highway - which is already underway - Paz and Villegas fear that Law 969 will open the park to all sorts of private endeavours. Article 9 of the law mentions the ‘opening of roads, highways, fluvial and aerial navigation systems, and others.’ Article 10 goes even further, inviting privados to ‘exploit natural renewable resources’ and to develop ‘productive activities.’

To activists such as Paz and Villegas, this reads like an environmental and social disaster. The inhabitants of the park are concerned that the territory will be colonised by cocaleros and highland farmers. Although the law forbids the illegal settling of colones and states that local populations and the environment will be respected in future projects, earlier this year, a meeting held by the communities of TIPNIS resulted in the rejection of the law.

Because of the highly politicised tone of the debate and the range of interests at hand, one aspect of the TIPNIS dilemma has been continually marginalised. TIPNIS is home to an uncountable number of species, many of which are endemic. Paz and Villegas suggest that if the plans move forward, in around 20 years the area could be subject to up to 70% deforestation, which would be catastrophic for the environment.

‘There could be another march,’ Paz says, who remains vague yet positive about the future of the park. According to her, international attention will be key if the road is to be stopped and environmental measures are to be taken seriously. In Villegas’s view, the people of TIPNIS have practically become ‘prisoners in their own land’, caught in layers of corruption, mismanagement, and bureaucracy.

As Paz acknowledges, the issue is much larger than the construction of a road in the jungle. ‘This is happening all over Latin America and the world,’ she says. Transcending political tendencies, economic impulses are pushing for a globalised and integrated economy. For now, those paying the price are the forests and the communities that live and depend on them.

Brasil, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay and Bolivia will meet this year in the city of Cochabamba to discuss the plans for the Bioceanic Train, a future railway that will link the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. Integration seems inevitable. Roads will most likely be built in the TIPNIS and across Bolivia. But perhaps the continent could integrate around a respect for the environment and its inhabitants, leaving behind its past of extractivism and colonisation. After all, that’s what President Morales promised when he pledged to the idea of Suma Qamaña: the notion of living in harmony.

Photos: Catriona Fraser

A glance at the María Auxiliadora community in Cochabamba

The history of Bolivia is rife with violence and disruption. Even the name of its presidential palace, el Palacio Quemado, is a nod to the country’s numerous coups and revolutions. Less visible, however, is the violence which remains hidden behind the closed doors of family rooms. In many parts of Bolivia, domestic violence stems from poverty, poor living conditions, and the polarising machismo and marianismo stereotypes. In 2016, 94 women were killed by their partners, and this year that number is expected to increase.

On one of the hills surrounding the city of Cochabamba, the women of the María Auxiliadora community are trying to maintain a place of sanctuary from domestic violence, a utopia for the many Bolivian women struggling in an oftentime brutal patriarchal world.

María Auxiliadora, a barrio which skirts the metropolis’ edges and looks down on the valley below with a tranquil silence a world apart from the blaring horns, smog and dirt of the urban sprawl, is home to over 400 families. It was founded in 1999 by Dona Rosemary and four other women with the mission to provide a sanctuary removed from the pressures of poverty and domestic violence that affect so many women. For a total of $200,000, 10 hectares of land were bought by these five women, the money being obtained partly through loans. Plots of land can be bought by families or single mothers – with homeless families given preference – for $3 per square metre.

The community has certain rules that residents and visitors alike must adhere to: no selling of property, no alcohol sales, a democratically elected municipal government with a female president and vice-president, and a communal labour ethos in which community members all work together every Sunday to build up the barrio’s resources.

Jo Maguire is a former NGO worker from England. After hearing that she was looking for somewhere to live, Dona Rosemary suggested she move in. Maguire has now been living in the community for 10 years. ‘It was just an amazing place to get involved with,’ she says while making freshly squeezed orange juice in her sunlit home. ‘I remember one guy fell off a roof. Every day, people took food to the family, people who have barely enough money to feed themselves.’

One of the primary focuses of the community is female autonomy, with the aim of reducing domestic violence. The excessive consumption of alcohol is a primary cause of domestic violence, and is something encouraged by the stereotyped image of machismo, a symbol of Latin American masculinity defined by strength and sexual aggression. In María Auxiliadora, it is illegal to buy or sell alcohol. This is just one of the ways in which domestic violence has been tackled by the community. Other ways include the blowing of a whistle if neighbours hear physical disputes. When the whistle is blown, a family liaison officer (a member of an elected committee) will enter the house and speak with the couple. If the violence continues, whoever is inciting it will be thrown out of the community. Maguire says this has happened four times since her arrival.

The community is mainly filled by people who have informal jobs such as taxi drivers, or those who sell food on the streets of the city below – jobs that do not provide a high income level. In the city, where tenacious landlords and poor living conditions abound, this can create domestic strife. But here in María Auxiliadora, cheap prices create a haven for those struggling below the poverty line. The community-lead ethos of solidarity also provides a safe environment free from the stress and cramped single-room life of the city. As recent research shows, the immediate social environment of any home is a leading factor in levels of domestic abuse and childhood performance at school. And according to Maguire, that’s evident here. ‘All the children do better here at school than those from the surrounding villages,’ she says while her son plays on his scooter outside.

A utopia? Perhaps.

The roots of that word—utopia—come from the Greek for ‘no place’, suggesting its confinement to the world of fiction. While the first nine years of this community’s life did verge on a utopia for those who lived here, recent rifts and divisions have formed over land distribution, causing this utopian vision to fade. The community’s cheap prices for land plots were viewed as competition by the surrounding loteadores. According to Maguire, beginning in 2010 some families demanded that the land be turned into private property, despite agreeing to the terms and regulations of the community upon arrival. This corruption has since been caught by the wind like the dust that blankets the barrio’s streets and spread through the community.

Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution grants rights to both collective and private property, as long as ‘the use made is not harmful to collective interests.’ Arguably, those who demand that the community revert to private property are acting outside the scope of the law. ‘The men didn’t see the benefits of the community, only the women,’ says Maguire. ‘They had alcohol-fuelled meetings, which resulted in physical violence. Once, 12 people were injured in clashes.’ Maguire also explains why the community isn’t receiving the full protections of the law: ‘When the new Constitution was created, communal land ownership was made legal. However, Dona Rosemary didn’t act quickly enough to gain legal autonomy for the community’s land.’

The women of María Auxiliadora are trying to maintain a place of sanctuary from domestic violence.

Even water is now a matter of dispute. Originally, everyone paid to have access to water, with profits going towards community infrastructure. Maguire says that eventually a group of around 40 people stopped paying for water, arguing that it had no legal status as it was not owned by the Bolivian government. The community split between those who wished for the land to remain communal, those who wanted private ownership and those caught in the middle, no longer paying for the water but also refusing to take sides.

These cracks within the community deepened over time, with neighbours turning on neighbours. Maguire recalls how her neighbour, a man she views as quiet and pleasant, threw dynamite into the face of Dona Rosemary’s husband. She says that the corruption within the community expanded to a governmental level, and resulted in Rosemary being imprisoned for four months. ‘The loteadores are the authority. They are the policeman and the politicians,’ Maguire says.

Eventually, in 2015, an electoral coup took place, with a pro-private-ownership leader taking power. Maguire no longer views the leaders of the community as viable – although they are still female, the community has lost its focus on the reduction of domestic violence. The whistles which once blew through the community as cries of concern for neighbours being abused are no longer heard. The barrio pulses with an empty silence.

‘We’re at a stalemate,’ Maguire says. When asked about the future, she shrugs her shoulders and gives a wry smile. ‘I really don’t know.’ María Auxiliadora once provided a safe haven from the cramped family life in the city, a place removed from domestic violence and the pressures of domineering landlords. It was a community based on trust. And like most utopias which remain enclosed like snow-globes in the world of fiction, the trust which this community based its dreams on proved too fragile a basis not to crack.

If the violence continues, whoever is inciting it will be thrown out of the community.

Photo: Nick Somers

‘¿Listo, Roberto? Donde estás? ¿Roberto, listo?’

It is a Thursday morning. March 2013. Eighteen years young, I still think that history is over. I am sitting on the floor of an empty bunk room in my new home in Sopocachi. I have just arrived.

All of my new flatmates have gone to some festival in Coroico. There will be hot tubs, hot springs, sex and presumably at least one actual Bolivian. I have not gone with them. No. Instead, I am sitting here. On the floor. In an empty bunk room. And no. I am not ready.

I sit in silence, hands hugging my knees like swept-up summer leaves in autumn; I hold them like hopes to my chest and pray the wind won't blow them away. I can hear cats scratching the tiles of the roof, and their claws screech like torn sheet music.

Pancaked on the floor, all I want is to call my mum. I want to hear her voice. Her love and care will breathe into me like butter melting into the aching pores of a crumpet. But I don't call her. Loudly, I lie: ‘¡Listo! ¡Vamos!’

The person shouting my name is my editor’s father. The night before, he had taken me out to dinner with his family. We liked each other a lot. Simon and Garfunkel can do that for a pairing.

At dinner, we had agreed to go to the market in El Alto the next morning. It is the best time to go, he said. In the sound of silence I agreed, but the silence lasted longer than four minutes and 22 seconds, so I got scared.

Walking to the bus now, the cholitas seem to snarl at me. Every red traffic light flashes like a heart threatening to quit. Cramming into a small minibus, we rub knees. I recoil from this physical connection. I am now holding my legs so tightly I could flatten my kneecaps into skipping stones. After an age, we arrive.

Bursting from the minibus, I'm thrown into the throng. We march relentlessly on. Him leading. Me behind, considering leaving. Without comment, we pass three llamas being milked, 400 used cars and a woman selling headless Barbie dolls. To my left, an island of doors for rent. To my right, concoctions of coca for miles. Everyone and everything is right here. I am out of control and utterly alone, in the world’s largest lost and found.

An age passes. We seem to have approached the final spinning cycle of whatever tombola we’ve been inadvertently entered into. Suddenly, the drum stops revolving. And just like that, it spits us out, into the arms of the loveliest woollen jumper I've ever seen.

You know the jumper I am talking about. You’ve probably even worn it once. It smells like a living thing. It hugs me like I am the leaves. Pulling it over my head, I let it linger around my nose, so I can breathe in that other air. Whole days have passed where the only good things I have thought have come from holding the seams to my skin.

In the sleeves, my stubby hands become brilliant fists of bright longing. The angled lines carving its design are my legs, tucked into a triangle so I could press them against my mother's calves when I am afraid of the dark. In these threaded rivers, I have buried every place I’ve been.

In this cradle I keep the stethoscope I would hold to my heart, so you might hear how fast my heart is beating when you kiss me. It’s at least four sizes too big for me, and it’s got holes the size of craters on the moon. But it’s home. My lovely woollen jumper.

Download

Download