This is the story of a girl—let’s call her Lizeth and let’s imagine she’s 10. Lizeth grows up in a small town at the edge of the Bolivian altiplano. She goes to public school, the proudly named Unidad Educativa Litoral Boliviano, which she has attended since primer grado. Every week starts the same way, with the raising of the Bolivian flag and the singing of the national anthem. Lizeth’s favourite classes are Science, Aymara, and Physical Education However, school days don’t last very long: only four to five hours. To fill her free time, she learns how to play rugby from a gringo who recently arrived to teach this unheard-of sport. (She and her friends greatly enjoyed playing against a boys’ team from La Paz and beating them with ease). The other day, her professor of Valores mentioned that an organisation involved in something called ‘integral education’ will come to the town and teach its spiritual programme in the afternoons.

This imaginary but very possible town is closer to reality than you might expect, with Lizeth’s story demonstrating very real changes to Bolivian schools.

Education throughout Bolivia is indeed developing, and has made major, if slow, strides since Law 1565 of 1994, introducing the idea of ‘intercultural bilingual education’ to the country. This has since been consolidated by Law 070 Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) in 2010 which is based around four main areas: decolonisation, plurilingualism, intra and interculturalism, and productive and communitarian education.

Inspired by the latest law and the defining concept of Vivir Bien (Suma Qamaña), the municipality of La Paz has started a programme of emotional intelligence to teach kids how to understand and manage their emotions. In order to advance a ‘secular, pluralist, and spiritual’ education, classes focusing exclusively on Catholicism have expanded their content to values, spirituality, and religions. The new law aims to redefine education to shape a new generation and a new decolonised identity, reinforcing what it means to be Bolivian.

The formation of one’s identity is certainly influenced by education with the Museo del Litoral, for example, illustrating the role of history and how the way it is taught affects the Bolivian psyche. Nevertheless, for some, school education doesn’t impact much; you can encounter some mechanics and antique photographers, self-taught professionals who, from a young age, have chosen their own path.

Bolivia does not lack spaces where people share and transmit their knowledge in unexpected ways, from a climbing school in the mining town of Llallagua to talks on the presence of LGBT+ literature in Bolivia; learning is not limited to the classroom.

The long-term effects of ASEP on Bolivian identity and future generations are yet to be seen. Unfortunately, it appears that Bolivia is still divided. There is a very clear disparity between rural and urban areas, rich and poor, boys and girls. Implementation of the law is slow at best. However, this glimpse of the state of education in Bolivia does shine a light on positive developments. ASEP promotes a vision of inclusivity, plurality, and interculturality, combined with an integral idea of education that can only bode well for the future of Bolivian students—young, old and self-taught.

For this issue, we travelled to the towns of Carmen Pampa in the Yungas, Santiago de Machaca in the altiplano, the mining town of Llallagua, we visited schools around La Paz and saw some of these changes in action. The students and teachers, masters and apprentices we have met, inspired us and showed us what the future of Bolivia might look like. For schoolchildren like Lizeth there are many opportunities opening up and we wanted to share some of these opportunities with you.

Photos: Fabián Zapata

Translation: Niall Flynn

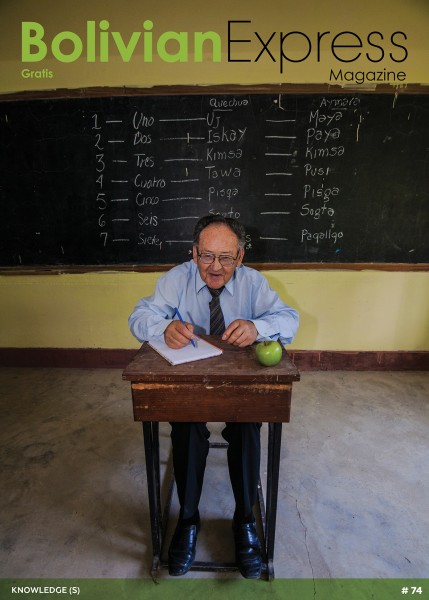

Portrait of Gregorio Alcón Beltrán

Gregorio Alcón Beltrán:

An intrepid traveller who spends his day relaxing in the square he has grown fond of and with his old friend, the sun, which has been inspiring his photographs for over half a century. He earns between 10 and 15 bolivianos per customer, offering a portfolio that includes a couple of small portraits he shoots with his old camera.

A master of light. A bronze-skinned gentleman wearing a grey jacket, clean shirt and striking tie. The esteemed 82-year-old photographer spends his afternoon astride a stool, under which he stores his equipment, and alongside his old camera named ‘Mobile machine’. Don Gregorio’s relationship with this square goes back over 50 years. He makes a living off portraits of paceños. He charges between 10 and 12 bolivianos for a set of 2 ID-card photos. After a long conversation swapping tales of our love of photography, discussing lenses and brands, this honourable man tells me about his style of work and how he had to adapt to technology to be able to continue in the field.

It turns out that Don Gregorio was one of the first photographers in Bolivia. He was trained by Marco Kavlin, whose family brought photographic innovation to La Paz. Kodak arrived to Bolivia bringing all the gadgets to teach the art of photography. Don Gregorio was amongst Kodak’s apprentices. But the interesting thing is that rather than the arrival of digital technology, it was counterfeiters’ low prices that put an end to this brand.

This photographer chiefly enjoyed travelling the country in military garrisons. He proudly recalls the good times: ‘I had the opportunity to travel all over Bolivia: Villazón, Tupiza, Los Yungas, Puerto Guaqui, the Chilean border, and many other places. In 5 minutes my photos were developed and ready, no matter where I was. This little box was more than sufficient for development, as well as great camera equipment, different lenses and tubes.’

‘Now I spend my afternoons here in the sun,’ he says, with a serene smile.

Our conversation became more and more enjoyable. He mentioned that the city government is urging them to continue using the cameras of yesteryear to preserve the square’s emblematic heritage, but says that this is no longer sustainable due to the cost of developing photos and the difficulty of sourcing the required materials. First and foremost, Don Gregorio would like to continue working with black and white film reel. But these photographers have had to modernise their methods to make their work profitable. They are artists who have survived the passing of time, but who retain their identity striking an amicable accord with technology. Don Gregorio showed me his new equipment and admitted that he has been using a digital camera for five years.

He uses a small, simple and discreet PowerShot camera and a printer that is hidden and padlocked under his seat. The brand new digital printer constitutes his entire studio, along with a couple of coloured backdrops.

As we chatted, a client arrived who wished to have her portrait taken. It was then that I witnessed Don Gregorio’s skills. Reading the intensity of the light, he oriented his seat to his subject; a lady in a traditional skirt. The sun is the only flash at his disposal, and I can testify that it is all he needs.

Don Gregorio is a member of a trade union made up of 600 independent photographers, and he lives entirely off this business, but says that it is no longer profitable. ‘Some young people come, but they quickly disappear because they say that they are not earning money. But I don’t have that option. I have been here for over 50 years. Photography is all I know. I’ve had a studio, I’ve taken portraits on my travels and I’ve been set up here for several years now,’ says the man who has seen the growth of this square, formerly known as Churubamba.

Many people seek him out because he is a well-known character. His most loyal and longstanding clients come to him today for portraits of their grandchildren. He is also sought by journalists and curious tourists who offer to buy his camera. He even appeared on television demonstrating his photo development techniques, and he has taught friends with an interest in photography.

These quirky figures who sit by their wooden tripods are greatly revered by society for capturing part of Bolivia’s history through their lenses; recognised for their modest but impeccable work that is capable of intimidating any professional studio.

I have now made a commitment to Don Gregorio. He promised to teach me his development techniques if I provide him with black and white film reel. Although many of his negatives have sadly been stolen, I am keen to see the work of this guardian of tradition; the composition of locomotives and the faces of traditional family life on camera reels never previously developed.

Photos: Fabián Zapata

Translation: Michael Protheroe

Servicing your car in La Paz

In almost every corner of the city, there are built-in makeshift mechanical workshops that meet the demand of ramshackle cars in La Paz. Inside there are hand-painted advertisements, made-up sponsors, disorganised tools, greasy walls, pornographic posters and abandoned cars. The mechanics are exceptionally inventive people who keep all kinds of scrap to create replacement parts for other cars.

I interviewed a few chapista mechanics and torneros to see how they work. I met two brothers: Reynaldo and José who are self taught, needing only to buy themselves some mechanics manuals in El Alto. Today they work from the door of their house, in the middle of the street. On the other hand, there is Don Macario, a personality much loved by Peta enthusiasts. Macario learned in Hansa workshops and today dedicates himself solely to these classic cars which have invaded the city.

Regardless of the amount of clients they have, the remarkable thing about these mechanics is that they work without specific prices. It is very easy to have a car running for a very low cost.

They could install a carburetor into a fuel injection car. With rubber residue and some welding, they give a Suzuki a Toyota’s suspension, a Subaru’s engine, tractor tyres and the electronic brain of a llama. I am obviously exaggerating, but their inventiveness did surprise me.

The Emotional Approach

At the forefront of new education developments are both private and public organisations strategising for equality in schools and empowering children through interdisciplinary classroom pedagogy. One of them is Programa Inteligencia Emocional (PIE), a project set up by the local government.

The instructor contorts his face into a mimetic frown and pretends to cry into his hands. After a few moments of gleeful giggling at the grown man's theatrics, 32 children join him in crying. The classroom erupts in wailing, and it is understood by every 5-year-old present that this concept, sadness, belongs to everyone.

Within this 2.5 hour session, a similar process will be repeated with five other emotions: anger, happiness, fear, disgust, surprise. In six other classrooms at this school in central La Paz, kindergarteners undergo the same emotional cycle with educators who have been trained to reach—and teach—where sensitivities lie.

This is the second of three emotional intelligence sessions that these children will participate in this year, as part of a government initiative to reduce the presence of violence in the community. According to the Pan American Health Organization, Bolivia has the highest rate of intimate-partner violence within South and Central America.

The Programa Inteligencia Emotional (PIE), which belongs to the Dirección de Coordinación de Políticas de Igualdad will visit 55 schools this year to provide sessions for young children on how to positively channel their emotions.

PIE's approach is threefold: 1) Teaching to recognising one's emotions, 2) Teaching to identify the emotions of others, and 3) Teaching to manage one’s emotions. After only two years of operation, the programme currently works with children ages 5-6 and 10-11, but hopes to serve youths ages 15-16 in the coming year.

Victor Hugo, the founder and coordinator of PIE, has built a curriculum on principles of Neuroscience, Evolutionary Psychology and Teaching Pedagogy. While responses from teachers and families have been consistently positive, Hugo acknowledges that the limited number of sessions per child poses a challenge to PIE's impact. He hopes the programme will inspire teacher training in emotional intelligence so the entire educative community can work towards eliminating discrimination and violence in Bolivia.

Website: http://igualdad.com.bo/

Download

Download