This is the story of a girl—let’s call her Lizeth and let’s imagine she’s 10. Lizeth grows up in a small town at the edge of the Bolivian altiplano. She goes to public school, the proudly named Unidad Educativa Litoral Boliviano, which she has attended since primer grado. Every week starts the same way, with the raising of the Bolivian flag and the singing of the national anthem. Lizeth’s favourite classes are Science, Aymara, and Physical Education However, school days don’t last very long: only four to five hours. To fill her free time, she learns how to play rugby from a gringo who recently arrived to teach this unheard-of sport. (She and her friends greatly enjoyed playing against a boys’ team from La Paz and beating them with ease). The other day, her professor of Valores mentioned that an organisation involved in something called ‘integral education’ will come to the town and teach its spiritual programme in the afternoons.

This imaginary but very possible town is closer to reality than you might expect, with Lizeth’s story demonstrating very real changes to Bolivian schools.

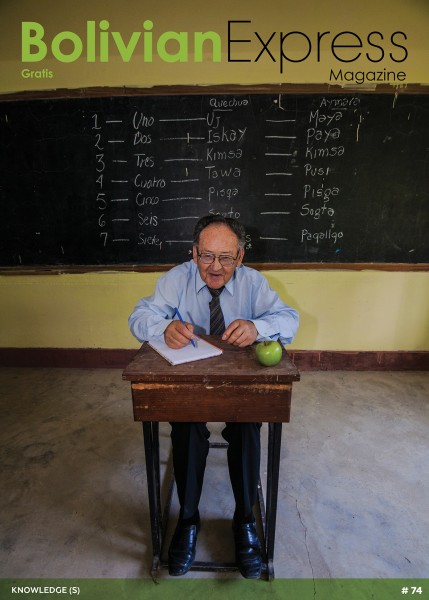

Education throughout Bolivia is indeed developing, and has made major, if slow, strides since Law 1565 of 1994, introducing the idea of ‘intercultural bilingual education’ to the country. This has since been consolidated by Law 070 Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) in 2010 which is based around four main areas: decolonisation, plurilingualism, intra and interculturalism, and productive and communitarian education.

Inspired by the latest law and the defining concept of Vivir Bien (Suma Qamaña), the municipality of La Paz has started a programme of emotional intelligence to teach kids how to understand and manage their emotions. In order to advance a ‘secular, pluralist, and spiritual’ education, classes focusing exclusively on Catholicism have expanded their content to values, spirituality, and religions. The new law aims to redefine education to shape a new generation and a new decolonised identity, reinforcing what it means to be Bolivian.

The formation of one’s identity is certainly influenced by education with the Museo del Litoral, for example, illustrating the role of history and how the way it is taught affects the Bolivian psyche. Nevertheless, for some, school education doesn’t impact much; you can encounter some mechanics and antique photographers, self-taught professionals who, from a young age, have chosen their own path.

Bolivia does not lack spaces where people share and transmit their knowledge in unexpected ways, from a climbing school in the mining town of Llallagua to talks on the presence of LGBT+ literature in Bolivia; learning is not limited to the classroom.

The long-term effects of ASEP on Bolivian identity and future generations are yet to be seen. Unfortunately, it appears that Bolivia is still divided. There is a very clear disparity between rural and urban areas, rich and poor, boys and girls. Implementation of the law is slow at best. However, this glimpse of the state of education in Bolivia does shine a light on positive developments. ASEP promotes a vision of inclusivity, plurality, and interculturality, combined with an integral idea of education that can only bode well for the future of Bolivian students—young, old and self-taught.

For this issue, we travelled to the towns of Carmen Pampa in the Yungas, Santiago de Machaca in the altiplano, the mining town of Llallagua, we visited schools around La Paz and saw some of these changes in action. The students and teachers, masters and apprentices we have met, inspired us and showed us what the future of Bolivia might look like. For schoolchildren like Lizeth there are many opportunities opening up and we wanted to share some of these opportunities with you.

Illustration: Hugo L. Cuéllar

The challenges of reform in a diverse Bolivia

Bolivia, or the Plurinational State of Bolivia, has 37 official languages. Roughly 70% of the population identifies as indigenous and 68% has mestizo ethnic ancestry. Against this complex background, the task of defining one’s identity is not a simple matter. How language learning fits into this vast web of linguistic and identity politics is undoubtedly equally complex. What I want to know is how educational reforms have been received and whether they are perceived as being successful or even relevant.

Recent educational reform began with the Law 1565, which introduced ‘intercultural bilingual education’ in 1994. The first article of the law states that ‘Bolivian education is intercultural and bilingual, because it assumes the cultural diversity of the country in an atmosphere of respect among all Bolivians, men and women.’ Historically, however, Bolivian society has been deeply stratified along ethnic lines. Colonialism still weighs heavily. Efforts to construct a Nation state and shape a unifying national identity have naturally problematised cultural diversity.

The more recent Law 070 Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) addresses four main areas for change in Bolivia’s educational system: decolonisation, plurilingualism, intra and interculturalism, as well as productive and communitarian education. Plurilingualism, in practice, means that children learn at least three languages: Spanish, an indigenous language and a foreign language, generally English.

Aiming to see policy in action, I visited a school in Miraflores, La Paz. I was largely disappointed however, as the teacher seemed unprepared for her class and after making the children recite some English and Aymara, admittedly quite enthusiastically, she informed me that there was no plan for the class. The director of the school clarified later that there was not a dedicated teacher of Aymara, which explained what happened to a certain extent. Although I may not have had a representative experience, my visit raises questions about large scale implementation.

To find out more, I spoke with Carlos Macusaya Cruz, a social communicator and educational activist. In his opinion, ASEP is ‘poetic, rhetorical, literary’ but in practical terms he believes that both rural and urban populations are more preoccupied with handling ‘modern’ technical knowledge, i.e. computers, mobile phones, cars. When asked about language teaching, Macusaya said, ‘I think that the practical sense has to do with people learning more than one language. It’s going to allow them locally, in Bolivia, to link to certain populations. If I speak Aymara I can communicate with the people for whom that language is more common, but it is also important to learn English because it’s a language that is handled in a globalising world.’

Efforts to construct a Nation state and shape a unifying ‘national’ identity have naturally problematised cultural diversity.

His viewpoint is one of practicality and not a romantic recuperation of ‘lost culture’. In his opinion, discourse on identity politics doesn’t seem to chime with people outside the government bubble. As he says, ‘It was never a problem of “I am Aymara, I am Guaraní, I don’t know.” It has always been linked to other topics such as: I am Aymara and because of this I am marginalised from work spaces, I have less agreements with the State, the State neglects my neighbourhood.’

There is a concern surrounding the essentialisation of indigenous cultures. That is, reducing them to stereotypes promoted by language teaching and attempting to recover a past that never really existed. ‘I remember saying somewhere several years ago that I was Aymara and people asked: “Where are your boat and your poncho?”,’ Macusaya says. ‘Looking for an essence in Andean cultures is like taking them from history’, he continues. ‘At the time of colonisation, the indigenous were portrayed as subhuman, as savages, as if that was their nature. In other discourses, promoted by the United Nations, the indigenous are no longer subhuman. Instead they speak with the cosmos, with animals, they are above others. In the end, it always reduces them, it denies their humanity.’

Pedro Apala Flores, Director General of the Plurinational Institute of Languages and Cultures in Santa Cruz, begs to differ, illustrating the other side of the debate regarding language education. ‘Already less shame is felt,’ he says, ‘already there is more openness in wanting to express things in their native languages. 10 or 15 years ago, that would have been very difficult. We hear people conversing in their language in public transport, in markets. Indigenous languages used to be family languages. A certain fear was felt because it categorised people as indigenous. So, there is that evolution, that empowerment.’

This matches a 2006 audit which claims that 71% of Bolivians identify as indigenous, whereas the 1992 census shows few Bolivians doing so. Getting back to the practical reality, however, I asked Apala Flores about the implementation of teaching and he was obfuscatory at best: ‘There are advances that we qualify as very positive and other things that are moving more slowly. In the topic of languages, we are moving with a firm but slow pace, because the linguistic complexity of this country is really alarming. For example: there are some teachers that speak indigenous languages but don’t write them.’ The teacher I met in Miraflores told me that she had to learn Aymara to teach it. Although a 2004 study suggests that reform has been better implemented in rural areas than in the cities, another study made in 2000, points out that only 25% of the indigenous population live in rural areas. It seems there are both practical and structural challenges for reform in a country where the process is only beginning.

There are practical and structural challenges for reform in a country where the process is only beginning.

If there is to be hope for a future generation in touch with indigenous culture and languages, the romantic and practical need to be balanced, with stereotyping and essentialising deftly navigated. Linguistic complexity aside, the teacher I spoke with told me, ‘The children find it difficult, but really interesting.’ Children, however, offered a different perspective. Urban children admitted they found language education boring and rural children seemed more enthusiastic. People want to be empowered, not forced into a prescriptive box. Whatever the way forward, people need to be respected, not reduced to essentialised images of cultures that ignore the complexities of reality.

With a series of LGBT+-related events running over the last few weeks in La Paz, I discovered a ‘¿Literatura homosexual en Bolivia?’ panel, and, not knowing much about Bolivian literature, I was intrigued. The idea of a dialogue on whether such a literature exists in Bolivia clashed with stereotypical preconceptions I had of the machista culture present in Latin America. The question marks in the title were telling, at least for me, as the questioning of the existence of the literature would seem to imply a questioning of the LGBT+ community in Bolivia, or rather their visibility.

Before the event took place however, I had an interview with one of the participants, Mónica Velásquez, an award-winning poet and professor of literature at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés. Velásquez took the conversation from a more literary point of view, claiming that the other people speaking at the event were ‘much more activist.’ We talked about how art and literature can allow someone to avoid reducing their work to their identity, citing one of her favourite poets, Fernando Pesoa, in saying, ‘Poetry invents subjectivities, and because of this you can have many voices.’ An interesting viewpoint, given the event Velásquez was soon to speak at was about a specific identity found in literature. She did, however, tell me, ‘I believe that one of the first functions of the art of these groups we have spoken about is about making them visible; art is testimonial.’ Velásquez further noted, though, that there was a danger surrounding agendas and ‘pamphlet literature’ or propaganda, that focusing too much on identity could diminish the quality of writing. The literature student in me tended to agree; the would-be activist was not so sure.

‘I believe that one of the first functions of the art of these groups we have spoken about is about making them visible; art is testimonial.’

—Mónica Velásquez

I headed to the event itself the next day, where Rosario Aquím, Lourdes Reynaga, Virginia Ayllon and Mónica Velásquez were speaking. The four analysed the presence of LGBT+ authors, characters and narratives in the canon and debated the merits of intermingling activism and literature. The event was quite popular, with people crowding a small room at the Centro Cultural de España, which fittingly appeared to be a kind of library. The evening culminated in a brief interview with the organiser of the event, Edgar Soliz Guzmán, also a poet. When asked why the conversatorio was important to have now, he told me that government legislation hasn’t solved enough of the problems faced by members of the LGBT+ community. ‘There is a sort of invisibility that exists in the canon and society,’ said Soliz Guzmán.

Identity is in art but does not constitute it.

Our conversation ended on the point that identity is in art but does not constitute it, which suggests to me that who you are seeps into what you do, but doesn’t necessarily have to define it. Soliz Guzmán said, ‘Literature isn’t written to justify existence.’ But it seems to me that the mere act of writing and looking for this literature helps to make the community visible and to normalise it. I agree, literature should not have to justify existence, but then nothing should have to justify existence. If art really is testimonial, then existence is implied.

Bolivia takes centre stage on the UN Security Council

On 7 April, the Bolivian ambassador to the United Nations, Sacha Llorenti Solíz, condemned the United States’ ‘unilateral attack’ on Syria during an emergency meeting of the Security Council, calling it a ‘serious violation of international law’. This was the first of what is certain to be many outspoken speeches that will be delivered by the Bolivian delegation during its time as a nonpermanent member of the influential United Nations Security Council for 2017–18 and as chair of the 1540 Committee, dealing with the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

The power of the Security Council is immense. As of 1 January 2017, for the first time in nearly 40 years, Bolivia has a seat on it – and, for the month of June, its chairmanship – able to influence peace agreements, impose sanctions and authorise military force (although the five permanent members maintain veto power). Since joining the UN in 1945, Bolivia has already made use of its international role by introducing important resolutions on environmental policy and human rights. The Andean country, usually consigned to the chorus in international affairs, is finally taking centre stage – along with nine other nonpermanent members – for the next two years. Now, under the spotlight of the UNSC, Bolivia will also be able to illuminate what it considers to be pressing issues that the international community must address.

But Bolivia’s star turn on the UNSC shouldn’t detract from the work it’s been performing over the last several years. In fact, Bolivia has mostly performed contrary to the desires of the United States. In 2015, it voted against the United States of America on eight out of 13 occasions at the United Nations. Many locals are proud of the fact that Bolivia can and does openly oppose the northern behemoth internationally on numerous issues. Felis, a bus driver in La Paz, says, ‘[The United States] has always controlled us, and I’m glad we are finally pushing forward our agenda and getting the recognition we deserve.’ There is hope in La Paz that Bolivia’s ambassador to the UN, Sacha Llorenti, will be able to continue standing up to the United States, fighting to ensure that Bolivia maintains its sovereignty and resists foreign interventions.

One of Bolivia’s successes is its campaign to represent indigenous peoples and bring their issues to the world's attention. Not only does the Bolivian constitution enshrine equal rights for indigenous peoples, but their rights are also backed up by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Adopted in 2007, the declaration, which Bolivia played an instrumental role in creating, ensures that the rights of indigenous people are upheld and maintained. Bolivia furthered its commitment to indigenous peoples by co-hosting the UN World Conference of Indigenous Peoples in 2014. This advocacy comes naturally to a country in which not only is the president indigenous, but also a majority of its population. ‘We will fight for everyone who has no voice locally, nationally or internationally,’ says Adriana Salvatierra, a young Bolivian senator from Santa Cruz.

Bolivia has also led the way for important UN Assembly resolutions on the environment, specifically the creation of the International Mother Earth Day, in 2009, and the recognition of the human right to water and sanitation, in 2010. The country’s UN delegation has also championed climate-change issues and ushered through resolutions ahead of the Climate Conference in Paris in 2016, which ended in an international agreement. Furthermore, President Evo Morales has championed climate-change action and water scarcity as key global issues, particularly relevant to the many Bolivians who faced a water crisis that led to dry taps in La Paz late last year. Using Bolivia’s specific water-supply problems to illustrate a global problem, Morales has also claimed that in ‘2050, four billion people will suffer from scarcity of water in the context of climate change.’ Lately, he has condemned the recent US withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement.

Bolivia is at the helm of the UNSC, which can influence peace agreements, impose sanctions and authorise military force.

Bolivia’s work on environmental issues at the United Nations is notable, and is certainly nothing new. Since 2009, Bolivia has prioritised preserving the environment – evident in the country’s constitution of 2009, which gives explicit rights to Mother Earth. In fact, Bolivia held the first-ever World People’s Conference on Climate Change in 2010, in which the Law of the Right of Mother Earth was drafted; in 2012, that bill was passed into Bolivian law.

In all, over the past nine years, Bolivia’s resolutions have been approved by the UN facing no opposition. In fact, Bolivia’s foreign minister claimed that ‘never before in the history of Bolivian diplomacy has the country had such an impact in the UN’. In the few months Bolivia has been on the Security Council, the country has already voiced its opinions on military action in Syria, as well as contributing to the debate on the issue of North Korea and nuclear security.

A former Bolivian minister of justice, Virginia Velasco, emphasises the importance of the environmental work that the Bolivian delegation to the UN is making headway on. ‘It’s great we are participating in the UN and getting our issues put down on the table and encouraging other nations to follow our lead on improving the natural world,’ she says.

Beyond its role in these important resolutions, Bolivia is further expanding its international prestige by introducing new and innovative ways to address century-long problems, namely in response to the ‘war on drugs’. One of those solutions, which stands in opposition to US-imposed crop eradication, allows poor farmers to grow small plots of coca for internal consumption. Salvatierra, the senator from Santa Cruz, says, ‘We have developed significantly over the last 10 years, and now countries are looking to us to create solutions.’ In fact, earlier this year, a Colombian delegation visited Cochabamba to assess Bolivia’s regulation of coca and interdiction of cocaine production.

Bolivia has taken on a new international role, an important moment in the global spotlight.

Bolivia has taken on a new international role, an important moment in the global spotlight. This increase in power and exposure could be the catalyst needed to help a country with economic potential to represent its people and the important issues affecting them, as well as to promote their prophetic voice on all matters of policy. At this exciting time for the country, Bolivia can make bold moves in the international diplomatic sphere.

Download

Download