This is the story of a girl—let’s call her Lizeth and let’s imagine she’s 10. Lizeth grows up in a small town at the edge of the Bolivian altiplano. She goes to public school, the proudly named Unidad Educativa Litoral Boliviano, which she has attended since primer grado. Every week starts the same way, with the raising of the Bolivian flag and the singing of the national anthem. Lizeth’s favourite classes are Science, Aymara, and Physical Education However, school days don’t last very long: only four to five hours. To fill her free time, she learns how to play rugby from a gringo who recently arrived to teach this unheard-of sport. (She and her friends greatly enjoyed playing against a boys’ team from La Paz and beating them with ease). The other day, her professor of Valores mentioned that an organisation involved in something called ‘integral education’ will come to the town and teach its spiritual programme in the afternoons.

This imaginary but very possible town is closer to reality than you might expect, with Lizeth’s story demonstrating very real changes to Bolivian schools.

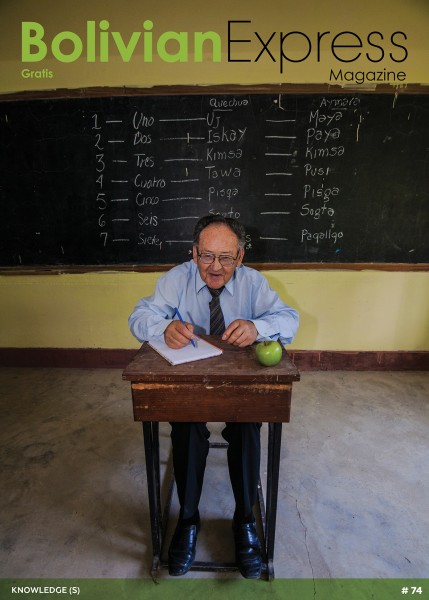

Education throughout Bolivia is indeed developing, and has made major, if slow, strides since Law 1565 of 1994, introducing the idea of ‘intercultural bilingual education’ to the country. This has since been consolidated by Law 070 Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) in 2010 which is based around four main areas: decolonisation, plurilingualism, intra and interculturalism, and productive and communitarian education.

Inspired by the latest law and the defining concept of Vivir Bien (Suma Qamaña), the municipality of La Paz has started a programme of emotional intelligence to teach kids how to understand and manage their emotions. In order to advance a ‘secular, pluralist, and spiritual’ education, classes focusing exclusively on Catholicism have expanded their content to values, spirituality, and religions. The new law aims to redefine education to shape a new generation and a new decolonised identity, reinforcing what it means to be Bolivian.

The formation of one’s identity is certainly influenced by education with the Museo del Litoral, for example, illustrating the role of history and how the way it is taught affects the Bolivian psyche. Nevertheless, for some, school education doesn’t impact much; you can encounter some mechanics and antique photographers, self-taught professionals who, from a young age, have chosen their own path.

Bolivia does not lack spaces where people share and transmit their knowledge in unexpected ways, from a climbing school in the mining town of Llallagua to talks on the presence of LGBT+ literature in Bolivia; learning is not limited to the classroom.

The long-term effects of ASEP on Bolivian identity and future generations are yet to be seen. Unfortunately, it appears that Bolivia is still divided. There is a very clear disparity between rural and urban areas, rich and poor, boys and girls. Implementation of the law is slow at best. However, this glimpse of the state of education in Bolivia does shine a light on positive developments. ASEP promotes a vision of inclusivity, plurality, and interculturality, combined with an integral idea of education that can only bode well for the future of Bolivian students—young, old and self-taught.

For this issue, we travelled to the towns of Carmen Pampa in the Yungas, Santiago de Machaca in the altiplano, the mining town of Llallagua, we visited schools around La Paz and saw some of these changes in action. The students and teachers, masters and apprentices we have met, inspired us and showed us what the future of Bolivia might look like. For schoolchildren like Lizeth there are many opportunities opening up and we wanted to share some of these opportunities with you.

Photo: Alvaro Manzano

ZERA: Lessons of Light

The state of public education in Bolivia is slowly improving despite slippery oversight and limited funding. Even massive reform from money-lending institutions won’t transform Bolivia into the generative, egalitarian nation it aims to be. Agents of change in education insist that true promise comes from within. Give a child a coin, and she’ll fill her stomach. Teach a child the tools for self-discovery, and she’ll tip stagnation.

The Integral Approach

Sharoll sits next to Tani in a well-lit office in San Miguel. Tani, age seven, has just drawn a rainbow flowing from her heart. Within the rainbow, sandwiched between the words ‘happiness’ and ‘love’, Tani has written ‘anger’ and ‘sadness’. Sharoll Osnat Fernandez Siñani, educator and director of ZERA, asks why. She helps Tani articulate her feelings and the two decide that the ‘light’ flowing through the prism of her heart refracts into grander light that projects onto others and leaves no room for negativity. Tani covers up her unwanted emotions with coloured markers and felt stickers. She glams up the rest of her symbolic diagram with neon glitter.

This is where spirituality comes in. ZERA, which means ‘seed’ in Hebrew, uses the globally acclaimed curriculum, Spirituality For Kids (SFK), as one of the sources for its programmes to implement tools for introspection through interactive methods for Bolivian youth.

Bolivia has long boasted a wealth of natural resources and cultural diversity, but has never been at the forefront of artistic, economic, or technological development. ZERA teaches students that they have the power to change the future, that there is no ‘light’ in bowing to former power relationships. Instead, there is a ‘seed’ worth fostering in every person, regardless of status or origin.

‘People are insecure everywhere, including Bolivia,’ says Sharoll, helping nine-year-old Maxi apply glue to the perimeters of his silhouette. ‘We need to teach children to look inside themselves, help them realise that they are already good and whole.’

Since its early work in women's prisons three years ago, ZERA has reached over 1,000 children. It conducts workshops in the city and countryside, weaving together expressive disciplines—art, dance, games, media, reading and writing—to ensure active engagement among its participants. The objective of the sessions are to provide Bolivian children of all backgrounds with the instruments necessary for a self-determining future.

According to ZERA’s philosophy, the instruments are empowering tools rather than imposed values. They are: Appreciation, Sharing, Effort, Wishes, Responsibility, Consciousness, Perseverance, Certainty, Unity and Love.

Sharoll nods at the paradox that selflessness might lead to personal benefits. ‘Actually, technical problems can be resolved quickly in education with the right administration, but what's essential is working in the community. Even with little resources, but with willingness to work with others, we can get what we want.’

It's a tough grab at gratification, but the kids get it. They learn that, ‘like a macaroni necklace', everyone is connected. Despite the fact that everyone has a different story, all people seek fulfillment.

Most of ZERA's lessons are expressed through the motif of light. Through these ‘classes of light’ children learn that their happiness is shared. In internalising this metaphor, participants of ZERA's programmes have been reported to enjoy improved relations with their peers, teachers, parents and greater community.

‘We're trying to raise conscious people,’ Sharoll tells me, ‘who are willing to sacrifice for others in ways that are unglamorous, and moreover continued daily. All of us, with our quirks and nuances, have something unique to give to the world.’

In the future, ZERA hopes to work with the global network Teach for All in its development of Teach for Bolivia, to ensure excellent education and inspiration across the nation.

For more info:

Facebook: ZERA Educación Integral

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8kY99bU79QA

...........................................................................................................................................................................................................

Photo: Lily Turner

The role of traditional dance in Bolivian education

When visiting the Unidad Educativa Piloto Adhemar Gehain in La Paz, I stand on the sidelines watching a Physical Education class take place. I explain to the teacher that I am learning about traditional dance in schools and she turns to the children to ask if they would like to do some dancing. The group of 30 children suddenly erupts in cheers and gleeful giggles.

The teacher then conducts the dances by varying rhythmic clapping. Each time, the children respond and recite different styles of dance, including the Diablada, Morenada and Caporales. I imagine them practicing their steps in front of the mirror at home in preparation for their end-of-year evaluation—a parade through the streets of the city.

In 2010, a new education law was passed in Bolivia with the aim to promote a greater sense of cultural identity in the young. As traditional dance has always been a significant characteristic of Bolivian culture, it begs the question as to whether the new law has had any effect on the role of dance in Bolivian society in general, or within the classroom in particular. Children grow up feeling an immense connection to their identity, cultivated through activities such as dance.

Children grow up feeling an immense connection to their identity.

In Bolivia, children are taught dance throughout their primary education in public schools, starting at age five. From a western perspective, the idea that dance is taught in schools is unusual, as it isn’t in the United Kingdom. Although the director of the Unidad Educativa Piloto Adhemar Gehain is surprised to hear, it is only in recent years that the activity has been advocated from a governmental level in the country.

Indeed, under President Evo Morales, Bolivia’s public education system has seen a dramatic reform. With the passing of the Law Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) in 2010, it is now necessary for children to speak Spanish, at least one indigenous language and one foreign, usually English. One of the main objectives of the ASEP law is to ‘provide historical and cultural elements to consolidate their own cultural identity and develop attitudes of intercultural relationship.’

Therefore, traditional dance can be seen as a vital part of this reform, ensuring the children of Bolivia grow up conscious of their cultural identity. In his book, Customs and Culture of Bolivia, author Javier A. Galván notes that ‘to promote this recent cultural pride, the Ministry of Education actually developed a folklore department.’

Although many will argue that the education reform has helped to reaffirm the importance of indigenous culture, some disagree. Carlos Macusaya Cruz, a social communicator whose focus is on decolonisation, tells me that it is ‘not necessary to make a dedicated Department of Folklore because Bolivian culture is not dying; therefore, it does not need to be rescued.’ Macusaya believes that folkloric traditions were ‘never under any threat’, as they are rooted deep in the identity of the Bolivian people.

Decolonisation is one aspect of the ASEP law that aims to recuperate the past and return to more authentic roots devoid of Western influence. For instance, at the last Gran Poder, which is a celebration of traditional Bolivian dances, outfits that were too revealing were prohibited in the name of respecting the past. However, this authenticity can seem slightly forced. As Macusaya explains, ‘the Morenada used to be played with a siku, which was a typical native wooden instrument. Today it is played with metal instruments. Also, fifty years ago women did not participate in the dance and today participate.’ These changes are arguably the result of a natural social progression in Bolivia and of inevitable global influences.

With or without the law, the joy that traditional dance in education brings to the children and those who teach it, suggests it will always have a place in the Bolivian education system. According to Lourdes Catorceno, a teacher at the Unidad Educativa Piloto Adhemar Gehain, ‘the law doesn’t make much of a difference, as the children always love the dancing lessons. They would take part regardless.’

‘The law doesn’t make much of a difference, as the children love the dancing lessons.’ —Lourdes Catorceno

In La Paz, specialist dance schools such as Artistik teach traditional dance to children who want to learn different styles beyond what they are taught in school. ‘Sometimes children come here simply to improve their technique’, the director, Karem Terrazas, tells me. When I ask Terrazas why she thinks traditional dance is so important, she places her hand on her chest and says it is simply because of the love for it.

Some argue it is not necessary to dedicate time and money to preserve Bolivian folklore. However, I believe there is no harm in promoting something that brings positivity and happiness to children across the country. Many teachers teach traditional dance not because it is in the curriculum, but because children love it.

Photo: Fabián Zapata

A Franco-Bolivian Brings Rugby to the Altiplano

I meet Jean Fontayne under the shadow of the Basilica of San Francisco, in central La Paz, on a crisp morning. We have a four-hour bus journey into the heart of the altiplano ahead of us. For Jean, this is a routine trip, as he has been travelling this route weekly since March. But today we miss the bus to Santiago de Machaca, a town that sits just south of Lake Titicaca on the altiplano near the Peruvian border. We are told that the bus will wait for us down the road so we frantically board a minibus heading in the same direction. I have little faith that the bus will be there waiting for us, but I am proved wrong. As we find our seats, we let out a harmonious sigh of relief and Jean remarks, ‘In Bolivia, everything is possible.’ This has never felt more true.

This philosophy—‘In Bolivia, everything is possible’—is what has inspired Jean throughout his life and led him to teach rugby in Santiago de Machaca. Here, in this small town of 4,000 people, something decidedly untraditional is occurring this year. We pick a quiet spot on the edge of the town to sit down and discuss what is happening.

Born in Oruro in 1990, Jean spent his first few months of life in an orphanage. He was discovered by a friend of a couple who would eventually become Jean’s parents, who noted that Jean ‘was holding on to life by holding on to him’ when he picked the baby up. The man phoned his friends back in France who had a desire to adopt and told them about this sweet Bolivian boy he had just met. Within weeks, Jean was adopted.

Growing up in France was fantastic, Jean recalls, but when he was 26 and had finished his studies, he decided to travel to his country of birth. He arrived in Santiago de Machaca a few months later, for work with Macha’k Wayra, a French non-governmental organisation. Based here since 2005, Macha’k Wayra educates populations with agricultural projects. While doing this, Jean soon began brainstorming other ways he could aid the community.

When asking him whether he found it difficult to transition into such a culturally different place from France, he expresses few qualms. He mentions how the language was tricky at first but he made sure, with intensive lessons, that when he returned to Bolivia he would be able to speak coherent Spanish.

‘In Bolivia, everything is possible.’

—Jean Fontayne

Having played rugby since he was five years old, Jean is passionate about the sport, and he is talented too—he was even pre-selected to play for the Bolivian national team. Seeing how much spare time the children had when not in school, he decided that teaching them rugby would be a productive use of their recreational time.

Setting up training sessions at the town’s artificial pitch, he taught boys and girls ages 8 to 12. After beginning with the basics, he could tell they were enjoying it and therefore wanted to expand and reach out to surrounding places. This past May, he organised a tournament for boys and girls from Santiago de Machaca alongside a mixed team from Catacora and a boys' team from La Paz’s Franco-Bolivian school. It was a great success, with most of the town turning up to watch the game and the children sharing traditional Andean food.

Jean says that the school day here ‘usually starts at 8:30am and ends at 12:30pm, meaning the children have a lot of free time to try and occupy themselves until their parents come home from work at around 6pm.' Jean’s rugby league is vital, providing the kids with an activity and an outlet for their energy.

It is clear how admired Jean is in Santiago. Everyone we pass recognises him. ‘¡Hola!’ and ‘Buenas tardes’ greetings fly at us from all angles. Children run up with arms extended, and Jean greets each one with similar and generous affection.

And Jean has more plans. He wants to open a socio-cultural centre where, in their free time, children can come and learn about different cultures. It will also be a place to read, watch movies and play games—activities that the majority of children here rarely have the opportunity to partake in.

Waiting to board the bus back to La Paz, I watch the town wake up with the rising sun. I feel fortunate to have visited a place where so much has positively changed in recent years.

Whilst watching the children of Santiago de Machaca make their way to school, I remember their infectious enthusiasm for rugby. Who would have thought that in such a rural town in a country obsessed with football, rugby could spark such a sense of community? I recall one of the first things Jean said to me just 24 hours before: ‘In Bolivia, everything is possible.’ The future for both Santiago de Machaca and Jean Fontayne looks blissfully bright.

Jean can be reached via the following:

Email: fontayne.jean@wanadoo.fr

Facebook: Humanitaire en Amérique du Sud

Website: santiagorugbyjuan.simplesite.com

Macha’k Wayra: www.machakwayra.org

Download

Download