I can’t count how many times I’ve seen it. Or maybe a better word is experience it. Whether bouncing in the crowded seats of a late bus from the altiplano or in the back of a taxi on my way home from an early-morning flight that just landed in El Alto, pre-dawn is the prime time to arrive in La Paz.

In those early-morning hours, there is a black blanket over the valley, hiding Illimani behind its thick curtain. You want to think the city is sleeping, but continued traffic and city sounds tell your hazy mind otherwise. But what gets you is the golden aura of La Paz, the orange, sodium glow that covers the valley in its unique nocturnal hue. The colour is a reminder of the clay bricks that make up the buildings of this city in daylight, but at night the colour has a different, soothing energy. As you approach the ledge of El Alto to begin the winding plunge down into the city’s depths, the lights of El Prado call you down, as the steep slope of Villa Fatima watches from across the valley. Down below to the right, you can make out the similar glimmer from Obrajes and beyond, Zona Sur giving off its own particular colour.

In these moments, no matter how tired I am, how dirty, how uncomfortable, I open my eyes wide to take in the fiery colour of nighttime La Paz.

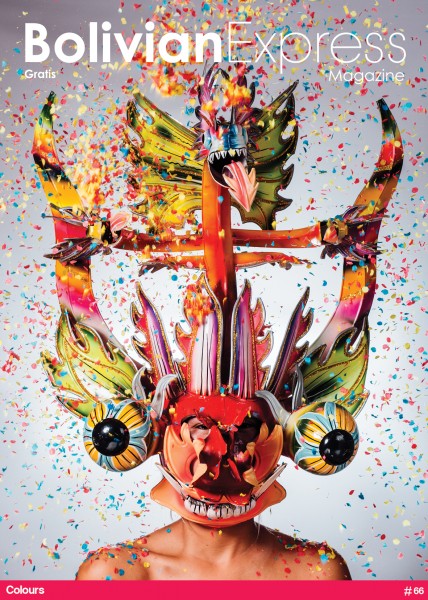

In this issue of Bolivian Express, we were inspired by these breathtaking moments, which so many of us have experienced living and working here. In day and night, colour takes on special meanings in Bolivia. From the grand swaths of purity in Sucre, Bolivia’s White City, to the rainbows of colors on towering murals breaking the greys and browns in the far reaches of El Alto, colours here continuously surprise. We see them in the blackened fingers and dark clothing of La Paz’s masked lustrabotas, and in the painted faces of its all-too-lovable clowns. And perhaps most notably, the artisans of Bolivia deploy colors to imbue specific meanings in their works, from elaborate, handmade textiles to ostentatious masks and costumes used in traditional dance. And with all the activity throughout the country, from the millions of people here living lives and changing its landscapes to the swaths of tourists visiting its incredible sites year after year, it is people who certainly bring the most colour to Bolivia.

My frequent nighttime rides down into La Paz will always be my strongest association with colour in Bolivia, but this country’s many shades and hues continue to enrich life here. Wherever one wanders, the colours are the first details to note. They contain secrets that can unlock so much of the mystery here, waiting to be understood. But for me, whether I have been gone for two days or two years, that hazy golden ride down the ridge from El Alto to La Paz conjures wonderful feelings inside me. And it reminds me of why I call this place home.

Photo: William Wroblewski

Indoor climbing in the city

Hidden in the Sopocachi neighbourhood of La Paz you will find La Cueva Boulder Gym. From the outside, the building looks like any ordinary home, but it houses La Paz’s premiere climbing wall. As the name suggests, the small entry conceals a cave-like space that is perfect for bouldering.

Bouldering is a climbing sport that is characterized by its short and explosive nature, which is why you don’t need high walls to practice it. When entering the cueva, I was surprised by the infinite climbing possibilities that had been created. On the night I visited, it was filled with a very enthusiastic climbing crowd.

Daniel Aramayo is the founder and owner of the gym, but above all he is a very experienced climber. He started climbing at the age of fifteen, inspired by his older brother to pick up climbing shoes and give it try. His first attempt wasn’t very successful, but after a few years he tried it again. From then onwards, he was infected by the climbing virus. ‘In order to improve your climbing skills you need to practise a lot,’ he says. ‘La Paz and its surrounding mountain ranges provide multiple possibilities to climb, but you depend on weather conditions.’ That is what encouraged him to build an indoor boulder gym with his climbing friends.

The gym offers sixty square meters of space and has 600 holds of all shapes and colours. They are colour-coded to mark different routes, from beginners to advanced levels. The Bolivian climbing community consists of fifty to sixty active members of different ages, but the cueva is not the only place where they come together. Daniel and his friends spend their weekends climbing at a rock formation called La Galleta, close to Zona Sur. They have set up over fifty routes by drilling bolts into the rocks in an area that is open to the public.

This group of climbers also hosts an event called Bloqueando. Its tenth edition will take place from the 28th to the 30th of October at Valle Challkupunku, 220km southwest of La Paz, near the Chilean border. Preparations for the anniversary include new boulder routes set up by the team.

José Luis Claure, an organizer of the event, is expecting about 150 participants of different climbing levels. This year, Bloqueando will offer climbing lessons, giving beginners a great opportunity to develop their skills. Besides climbing, there will be side activities to sit back and relax from the rocks, including volleyball, slacklining, and movies. As Claure explains, ‘It’s quite tough to climb the whole day, we need to chill as well.’

The organizers have made great efforts to prepare an promising event full of climbing, great food, and parties, surrounded by a beautiful landscape in the middle of nowhere, where you will pitch your tent (if you are lucky) under a sky full of stars.

Registration for Bloqueando is open. For more information, visit http://bloqueando.com/.

Photos: Iván Rodríguez Petkovic .

Camijeta image Courtesy of Musef

Decoding the myths of local communities

Walking down the crowded streets of Mercado Rodriguez, surrounded by vendors selling odds and ends, I slow down my pace to avoid bumping into a cholita; on her back is a bulky and colourful wrap full of groceries. As I pick up my speed and observe the assortments of stalls and merchants, I notice that many of these women are wearing the same sort of wrap. When I take a closer look, I discover the variety of these colourful pieces of clothing, their patterns distinguished by different materials, symbols, and colours.

On these pieces of cloth, called aguayos, men and women write and paint stories of their community, using the symbols of their culture. These stories change depending on the region, each of which has distinctive colours, designs, and techniques. The fabrics have abstract designs, indigenous and figurative representations, sometimes surreal monsters.

Although there are many places in Bolivia where people use authentic aguayos, most of the bright and colourful ones that roam on the street are likely to be industrial products. They come from Peru, and are distributed throughout Latin America for very low prices. Although these pieces are common on the streets of La Paz, you can find traditional aguayos in rural areas of the country, where the weavings embody the stories of a community.

Jalq’a

Produced by the very remote Jalq’a community near Potosí, this piece of aguayo is a very rich and complex textile art. The rectangular Jalq’a tissues are often characterized by a single space, without having any segmentation or strips on the side. The red and black colours represent the darkness in which these communities lived, which some say existed in a time ‘when the sun was the moon’. The design is chaotic; there are figures everywhere, of different sizes. It is unclear where they begin or end. The Jalq’a pattern represents a dark world filled with strange beings that belong to a non-human society. The most common creation is a fantastic animal, called a khuru, which means ‘wild’ and ‘untamed’ in Quechua. Their presence indicates the unknown, a place where man is not dominating.

Tarabuco

In contrast to the Jalq’a weaving, this material has more real and humane representations and is influenced by the Spanish conquistadores. The Tarabuco community is located near Sucre, which explains why it uses occidental symbols such as horses. Tarabuco clothes are always symmetrically organized in strips of varying widths. This also applies to the symbols, which have a definite nature, including pictures of detailed animals and humans. The scenes depict important moments of everyday life, like women weaving and men playing the flute.

Kalamarka

On the altiplano near La Paz, communities have been producing the same sort of aguayos for the past hundred years. These are characterized by the alternating use of pampas and saltas, where the plain monochrome areas are defined as pampas, and saltas refers to the areas containing symbols. The salta illustrates the quotidian life of these communities by using symbols of their surroundings, mainly referring to the countryside. This specific aguayo includes a key motif with hooks ending in sharp points at top and bottom, portraying the insignia of the local healers. Typical to this type of aguayo is the use of natural colours, such as white, blue, and red.

Camijeta

Far-flung in the Amazon region of Bolivia, you will be able to find this very traditional type of textile. This sleeveless tunic is worn by Yurakaré men from the Beni department in ceremonial settings. It is organized into five vertical and five horizontal rows with the same sort of design. The oval shapes resemble typical Amazonian seeds, flowers, or fruits, such as cacao or achiote. The colours vary in each row. Yellow is considered unlucky and could indicate a bad harvest. Camijetas are traditionally made from plant fibre and cotton, which give them a vegetable tone.

The author would like to thank Milton Eyzaguirre and the rest of the team at the Museo Nacional de Etnografía y Folklore, as well as the Museo de Textiles Andinos Bolivianos, for help with the research of this article.

Photo: Alejandro Loayza Grisi

A Changing Landscape

Making my way down to Copacabana by bus, leaving behind the crowded streets of La Paz, I see the landscape changing. From an urban jungle of diesel-spewing minivans, dust, and rubbish, to a place where natural beauty and fresh air is the norm. As I wander along the shores of Lake Titicaca I am struck by an intriguing and serene feeling, but my excitement over the lake’s many allures is disrupted by the amount of rubbish I walk by. Further along in my stroll, I find more junk that pollutes the lake. No one seems to pay attention to this sad and worrying situation. Children are playing carelessly in the water while their parents enjoy truchas criollas on the lakeside.

This dichotomy is representative of the future of the country’s flora and fauna. The lake is a great example of Bolivia’s extraordinary beauty and is home to a phenomenal and colourful biodiversity. Its future, however, is at risk. Climate change and pollution are some of the culprits devastating the Bolivian environment, but how do we, as a society, connect with these issues?

This is the question behind Planeta Bolivia, a collection of short films that shows the country’s beauty in contrast with shocking images of the damage that has been done to ecosystems in Bolivia. The series was made by former president Carlos D. Mesa, anthropologist Ramiro Molina, environmentalist Juan Carlos Enríquez and film producer Marcos Loayza. It warns of climate change and denounces environmental contamination. It creates a feeling of confrontation and shame in regard to our personal environmental footprint.

The protagonists of this complex environmental reality are water, land, climate change, and population density in Bolivian cities. The images of Lago Titicaca are telling. ‘People throw all kinds of human trash into the rivers that drain into the lake,’ Loayza points out. ‘The problem starts in El Alto, where most people pay little attention to the degradation of water resources.’ As a result, the image of the world’s largest high-altitude freshwater lake is characterized by dirty shorelines full of soda-cans, rubbish, and animal waste.

The first film in the series shows discarded bottles floating in the lake, causing plastic pollution and disturbing the fish population. It captures green algae extending towards the shores of the peaceful agricultural islands that are home to indigenous communities. It displays rust-coloured rivers fed by wastewater from mineral processing. On top of pollution, its water level is decreasing. The lake suffers from severe drought and the glaciers that fill it are retreating. ‘It is a process that has developed much faster than we expected, and it is likely to become the most important effect of climate change,’ says former president Mesa. The polluted water that flows downstream from El Alto has reduced the availability of clean water for irrigation and domestic use in the area.

The filmmakers adopt a bold and unusual approach in their filmmaking. The documentaries don’t rely on traditional techniques, such as a voice-overs or testimonials of people explaining a wrongdoing. ‘We present the problem,’ Mesa says, ‘and insist that people think about how they can face these big issues. We are not pointing at the guilty, we are not proposing solutions, we want to change the people’s perception of environmental problems.’

‘To be realistic, we are not going to transform the world or Bolivia with our films, but we think we can contribute to a new environmental awareness,’ Mesa says, optimistically.

‘At this moment, Bolivians have a tendency to think that environmental issues are problems of the other,’ says Loayza. ‘Not only the United States, Europe, or even big industries are facing and causing these dilemmas. We also have a fragile ecosystem.’ According to Loayza, resilience is key to a changing environmental perception. He believes that if one person changes his or her mind-set, it can inspire other people to follow.

As important as personal responsibility is, Mesa doesn’t rescind the importance of collective accountability: globally, nationally, and locally. ‘For example,’ he explains, ‘the government of Bolivia has to adopt a much more committed position in this environmental dialogue. The current government is favourable to this discourse because it claims to defend and to be a brother of the environment,’ he says, in reference to the Ley de Derechos de la Madre Tierra, which defines Pachamama as a collective subject of public interest.

Mesa critiques the government for its lack of rigorous policies that protect Bolivian nature. ‘The state is in a very preliminary position when it comes to collaboration with other stakeholders,’ he says. Although, one should take into account its position; natural resources are crucial for the country, and demanding that they are not extracted deprives the country from economic development other nations have enjoyed from doings in the past. And the private sector also has a share in pushing the environmental systems towards their limits. As an answer, Mesa argues that countries, companies, and communities should share responsibility and have better relations in order to work collectively on environmental protection.

In the case of the lake, which borders Peru and is home to several communities, cooperation is crucial for its future. By using different media platforms, including social networks, the filmmakers developed a mechanism that allows anyone to participate interactively in this debate and exchange their opinions. In order to reach a younger audience, the films are shown at schools. ‘If they change their lifestyle now, it will give hope to the future,’ Loayza says firmly, referring to the next generation.

I think about my experience on the lake and its polluted waters and recall the people I saw there. They seem unaware that Copacabana’s unique territory is exposed to contamination. Two images come to mind, that of a dirty shoreline and people enjoying comfort.

Sometimes people seem to go on without thinking about the future. I can see a lack of environmental consciousness in some people, and understand why it is necessary to promote this conversation. The lake allowed me to see the face of environmental degradation. Mesa and his team have been able to capture this bitter development, and the pictures presented in the films are almost frightening. The country’s physical beauty and its impurities are impressive and have the same effect on the viewer as the lake had on me. This contrast will hopefully make people aware of their role in the environment and inspire them to contribute to a healthier lake.

Download

Download