I can’t count how many times I’ve seen it. Or maybe a better word is experience it. Whether bouncing in the crowded seats of a late bus from the altiplano or in the back of a taxi on my way home from an early-morning flight that just landed in El Alto, pre-dawn is the prime time to arrive in La Paz.

In those early-morning hours, there is a black blanket over the valley, hiding Illimani behind its thick curtain. You want to think the city is sleeping, but continued traffic and city sounds tell your hazy mind otherwise. But what gets you is the golden aura of La Paz, the orange, sodium glow that covers the valley in its unique nocturnal hue. The colour is a reminder of the clay bricks that make up the buildings of this city in daylight, but at night the colour has a different, soothing energy. As you approach the ledge of El Alto to begin the winding plunge down into the city’s depths, the lights of El Prado call you down, as the steep slope of Villa Fatima watches from across the valley. Down below to the right, you can make out the similar glimmer from Obrajes and beyond, Zona Sur giving off its own particular colour.

In these moments, no matter how tired I am, how dirty, how uncomfortable, I open my eyes wide to take in the fiery colour of nighttime La Paz.

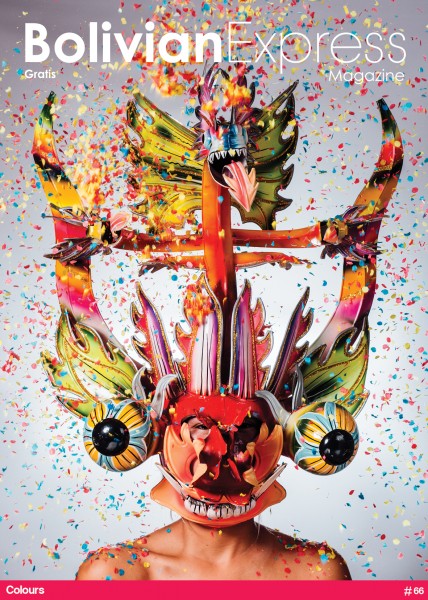

In this issue of Bolivian Express, we were inspired by these breathtaking moments, which so many of us have experienced living and working here. In day and night, colour takes on special meanings in Bolivia. From the grand swaths of purity in Sucre, Bolivia’s White City, to the rainbows of colors on towering murals breaking the greys and browns in the far reaches of El Alto, colours here continuously surprise. We see them in the blackened fingers and dark clothing of La Paz’s masked lustrabotas, and in the painted faces of its all-too-lovable clowns. And perhaps most notably, the artisans of Bolivia deploy colors to imbue specific meanings in their works, from elaborate, handmade textiles to ostentatious masks and costumes used in traditional dance. And with all the activity throughout the country, from the millions of people here living lives and changing its landscapes to the swaths of tourists visiting its incredible sites year after year, it is people who certainly bring the most colour to Bolivia.

My frequent nighttime rides down into La Paz will always be my strongest association with colour in Bolivia, but this country’s many shades and hues continue to enrich life here. Wherever one wanders, the colours are the first details to note. They contain secrets that can unlock so much of the mystery here, waiting to be understood. But for me, whether I have been gone for two days or two years, that hazy golden ride down the ridge from El Alto to La Paz conjures wonderful feelings inside me. And it reminds me of why I call this place home.

Photo: Alexis Galanis

The Struggles of Recognizing Legal Pluralism in Bolivia

Blaring trumpets and crashing drums reverberate through the white walls of Sucre. On Calle Dalence, hundreds of people, adorned in an array of colours, march up the narrow street, singing and dancing their way to the picturesque Plaza de Anzures. Here the celebration escalates; the Wiphala proudly flies, and an ever-growing crowd looks on as performers from every indigenous community in Bolivia come together to celebrate the plurinational culture of Bolivia.

Samuel Flores, the former leader of the marka Quila Quila in the department of Chuquisaca, and now a permanent advisor to the the Tribunal of Indigenous Justice, says this isn’t merely a celebration, but a protest against the injustices committed against the indigenous nations of Bolivia. ‘The plurinational state is two things,’ he says. ‘It’s the system of the indigenous nations of Bolivia, and the democratic, globalised system of Morales’s state.’ Flores’ words convey a strong sense of bitterness and injustice, which arise from the apparent disjunction between these two systems. ‘We have to fight so that “the plurinational state” is more than just a name.’

The Plurinational State of Bolivia comprises more than 50 precolonial indigenous nations. For centuries, they have carried out justice in their territories according to the specific customs and methods of their respective cultures. In 2009, the new Bolivian Constitution recognised for the first time the indigenous nations’ rights to autonomy and self-determination as equal to that of the state’s justice system. But this idea doesn’t always translate to action.

After an intense morning of constructive discussion and debate, the summit breaks for lunch. In the central market, Mama T’alla Florinda González Pérez, the elected indigenous leader from the marka Salinas, in the department of Oruro, explains the challenges of her role. ‘Our authority is recognised by the state, but the Ley de Deslinde Jurisdiccional (‘Law of Jurisdictional Delineation’) works against us,’ she says.

Introduced in 2010, the Ley de Deslinde demarcates between the state and indigenous jurisdictions and sets up the terms of coordination and cooperation between them. Articles 8, 9, and 10 of the law impose certain limitations upon the exercise of indigenous justice, dictating that it may only be applied when certain criteria are fulfilled, including that the person involved must be from the same nation as the indigenous authority and the issues at hand must have taken place in the territory of the indigenous authority. The 10th article is the most strongly contested. It establishes that certain crimes, such as child abuse, rape, homicide, and drug trafficking, are exclusively under jurisdiction of the Bolivian state.

‘The law essentially means that we are only allowed to deal with disputes over land, whereas before we dealt with everything,’ Florinda says. She argues that who commits a crime and what type of crime is committed are immaterial and that these restrictions contradict the authority conferred to indigenous leaders in the Constitution. ‘If something happens in our territory, that’s it; it should fall within our jurisdiction.’

Additionally, says Florinda, the constitutional guarantee of equality between indigenous justice and the state is not being observed. ‘We don’t have a house of justice, technical support, or any kind of budget,’ she says. This makes the job of the mallku more or less impossible to carry out. When a case does fulfil the criteria identified by the Ley de Deslinde, the mallku frequently doesn’t have the economic or bureaucratic resources to pursue a case.

Florinda’s complaints are vehement and well-argued, but is her complete dismissal of the Ley de Deslinde entirely fair? The Ley de Deslinde not only sets limits, but validates the Jurisdiction of Indigenous Justice and sets up the terms of coordination which facilitate its application. Moreover, the limitations have an essential function: ensuring that the laws and principles of the state are upheld above all else. It is within reason that the state should wish to control issues as serious as rape and homicide. More importantly, its desire to do so does not, according to Marcos García-Tornel Calderón, an expert in constitutional law, undermine indigenous authority or the equality accorded to their jurisdiction. ‘I don’t think it violates the principle of jurisdictional equality, because a jurisdiction can exist with a limited field of application and still maintain an equal status.’

However, García-Tornel believes that the extent of limitations listed in the Ley de Deslinde is excessive and problematic. ‘If you look carefully at the list,’ he says, ‘the scope of matters within the Jurisdiction of Indigenous justice is reduced to a bare minimum.’ In this respect, the law does violate the Constitution, although not in a strictly legal sense. ‘It’s more a violation of the spirit of the Constitution and its plurinational nature, and a lack of due respect for the indigenous nations of Bolivia’.

On the last day of the summit, the indigenous leaders announce their conclusions: to mandate the plurinational constitutional tribunal, declaring the Ley de Deslinde unconstitutional and demanding the adequate financial support to fortify coordination and cooperation between the jurisdiction of indigenous justice and the state. ‘The state needs to understand that we, too, have a right to help build this Plurinational State of Bolivia, and we’re not merely acting on an impulse or desire,’ says Tata Francisco Ibarra Ortega of the Q’hara Q’hara nation, from Potosí. ‘This is a reality – an official decision made by an official jurisdiction of the state. We needn’t be afraid; we are prepared to help build this state in this critical moment when we are needed most.’

But others aren’t nearly as accommodationist. ‘The state is the one common enemy of the indigenous nations of Bolivia,’ says Samuel Flores. ‘An enemy against whom we, the indigenous communities, need to fight.’ For Flores, the severe limitations imposed by the Ley de Deslinde constitute a form of subordination, fomenting scathing views towards the concept of plurinationalism. ‘How can we continue to be a part of a state in which we continue to be subordinated? The state is just using us to put on the poncho and the pollera and talk about the indigenous communities on an international level,’ Flores continues. ‘But in practice? Little, if anything at all…. That’s why we’re here, fighting.’

Flores maintains that the many indigenous nations represented here at the summit are all on the same page. His words, however, suggest a relationship of conflict with the state and a desire for autonomy that contradicts the proposal of strengthened collaboration widely promoted at the press conference.

Conflict or cooperation? Indigenous autonomy or plurinationalism? The Ley de Deslinde, and the controversy it has stirred, has exposed the frighteningly fine line between division and unification in the complex politics of Bolivia.

Photo: Alexis Galanis

The stories that lie behind the walls of Sucre

The city is known by many names: Charcas, La Plata, Sucre. The uniform whiteness of its walls covers up its seismic historical shifts and complex identity. But the nooks and crannies of each building and street belie the city’s pallor and reveals the colourful personality of Bolivia’s White City.

It’s 9 am in Bolivia’s most beautiful and iconic square, Plaza 25 de Mayo. The city centre is slowly waking up. Sucrenses sit peacefully, reading newspapers among palm trees, flowers, and the towering statue of the city’s eponymous hero, Antonio José de Sucre. The morning sun shines upon the stunning white façades that frame the square. Tranquillity and fierce Bolivian pride fill the air in equal measure at the heart of the constitutional capital of Bolivia.

It was here that the first cries of freedom where proclaimed on the 25th of May, 1809. To my right is the monument of that proclamation, the most historically significant building in Bolivia, the House of Freedom. Walking through the door, I immediately find myself in an open courtyard. To my left, I’m greeted by the recently erected statue of Apiaguaiki Tumpa, the legendary Guaraní cacique who fought for his people’s liberty in the late 19th century.

In each room, a pivotal period of Bolivian history reveals itself. The highlight is undoubtedly the Hall of Independence: a huge open space, filled with silence, ornate decoration, momentous artefacts and portraits of Bolivia’s national heroes, that feels almost sacred. The feeling is, in part, due to the fact that the hall was constructed as a chapel by the Jesuits in 1621. Although the Jesuits were exiled from the country in the 18th century, the fine Mudéjar coffered ceiling and the stunning gold-leaf altar are a welcome reminder of their lasting imprint.

The room’s air of sanctity owes more, however, to the crucial events that took place here. It was here that the Act of Independence from Alto Peru was signed on the 6th August, 1825. The historical document remains the centrepiece of the hall, framed, mounted, and overlooked by a portrait of Simón Bolivar. In this room, Bolívar drafted the first constitution of Bolivia, awarded the presidency of the Republic to Antonio José de Sucre, and declared the newly named city the constitutional capital of the country.

Leaving the House of Freedom, the imperious Baroque façade of the Chuquisaca Governorship Palace and the domineering bell-tower of the Renaissance cathedral stand side by side as monuments from two distinct periods of Sucre’s history. With the motto “La Unidad es Fuerza” (Unity is Strength) embossed beneath its central arch, the former Presidential Palace proudly amplifies the republican spirit of the House of Freedom. The Cathedral’s bell tower reaches high into Sucre’s ever-blue sky and looks out at the thirty-five churches scattered around the white cityscape, an indelible landmark that points to a pre-Republican past.

In this city, white churches have sprouted everywhere. The first of these, the Iglesia de San Francisco, is just one block from the main square. An in-depth tour takes me through the delicate history of the building, which served as the primary living quarters of Villa de la Plata after its foundation in 1538. On the rooftop stands the Liberty Bell, which tolled to signal the first cries of freedom in 1809. Every 25th of May, the President of Bolivia returns to this church to ring the bell in commemoration of the nation’s independence.

It is 1 pm: lunchtime. Next to San Francisco, rather conveniently, is the Central Market. Wading my way through a sea of fruit stalls, I eventually arrive in the maze of the market’s main building. After stumbling around for longer than I care to admit, I discover ‘7 Lunares’, which I’m told prepares the best the chorizos in the world. Not a choripan, they tell me, but a chorizo chuquisaqueño. A double-chorizo sandwich sets me back 13 bolivianos. Was it the best in the world? Maybe.

Appetite satisfied, I make my way back to the main square via the Museum of National Ethnography and Folklore (MUSEF), housed in an impressive colonial building that used to be the National Bank of Bolivia. With no entry fee, it’s a great place to learn about the history and customs of Bolivia’s ethnic groups. Among its permanent exhibitions is the visually stunning mask museum on the first floor, showcasing the extravagant and colourful masks used in festivities by various indigenous groups.

The two most famous chocolate shops in Sucre are a short walk from the museum. Since Sucre is the chocolate capital of Bolivia, any chocolate lover needs to visit at least one of the two. Some will vouch for ‘Chocolates Para Ti’’ and some for ‘Taboada’. Both can be found on the corner of Plaza 25 de Mayo where Arenales and Arce meet. In order to join the debate, I’ll say that my hot chocolate from ‘Chocolates Para Ti’ was fabulous, an ideal mid-afternoon treat to keep me going through the day.

Pausing to look back at the white walls and terracotta roofs of the busy centre, I climb my way up to La Recoleta, zig-zagging from Calle Calvo to the charming and still streets of Grau and Dalence. As I approach the mirador, the streets become more narrow and quiet, and their names get weirder: ‘Black Cat Street’, ‘Grey Cat Street’, ‘White Cat Street’. Untouched by the hints of modernity that brush the edges of central Sucre, this is a strange and eerie area to walk through, filled with history and superstition. During the Chaco War, part of the local population was widowed, which lead to a boom in the numbers of our small feline friends. It is said that a dark and seductive widow roams these streets at night, calling drunkards in by name and making them disappear mysteriously.

The Cathedral’s bell-tower reaches high into Sucre’s ever-blue sky and looks out at the thirty-five churches scattered around the white cityscape.

It is 5 o’clock when I arrive at Plaza Anzures, and it becomes clear why the Franciscan order chose to build a monastery there as a retirement home for elderly monks. The church sits peacefully in the folds of Cerro Churuquella, looking upon the open ochre space of the plaza, where school children gather in the late afternoon. I take a seat at Cafe Mirador, barely tucked beneath the arches of the lookout, and sip on a glass of red wine as the sun slowly sets on a sea of white and terracotta.

Photo: Alexis Galanis

Celebrated Artist Mamani Mamani’s Towering Murals

As you drive through El Alto to zona Mercedario, the landscape becomes stark, and the hectic hubbub of La Ceja softens to silent desolation. Clouds of dust from the occasional passing vehicle seep through the car window as paved roads give way to dirt tracks. Over the horizon, seven towering multicoloured buildings at the heart of this neighbourhood emphatically break the terracotta monotony of the barren suburban landscape.

The greens, reds, whites, yellows, blues, oranges, and purples of the Wiphala swirl around, loudly but delicately singing of Andean heritage across 14 stunning murals in this astonishing, unprecedented project undertaken by the Aymara artist Roberto Mamani Mamani. As the afternoon sun pushes through the subsiding clouds, these sky-high kaleidoscopic figures come to life. The walls glimmer, their colours enliven, and each window becomes its own work of art, dozens of canvases of reflected paint set within these colourful giants.

Download

Download