I can’t count how many times I’ve seen it. Or maybe a better word is experience it. Whether bouncing in the crowded seats of a late bus from the altiplano or in the back of a taxi on my way home from an early-morning flight that just landed in El Alto, pre-dawn is the prime time to arrive in La Paz.

In those early-morning hours, there is a black blanket over the valley, hiding Illimani behind its thick curtain. You want to think the city is sleeping, but continued traffic and city sounds tell your hazy mind otherwise. But what gets you is the golden aura of La Paz, the orange, sodium glow that covers the valley in its unique nocturnal hue. The colour is a reminder of the clay bricks that make up the buildings of this city in daylight, but at night the colour has a different, soothing energy. As you approach the ledge of El Alto to begin the winding plunge down into the city’s depths, the lights of El Prado call you down, as the steep slope of Villa Fatima watches from across the valley. Down below to the right, you can make out the similar glimmer from Obrajes and beyond, Zona Sur giving off its own particular colour.

In these moments, no matter how tired I am, how dirty, how uncomfortable, I open my eyes wide to take in the fiery colour of nighttime La Paz.

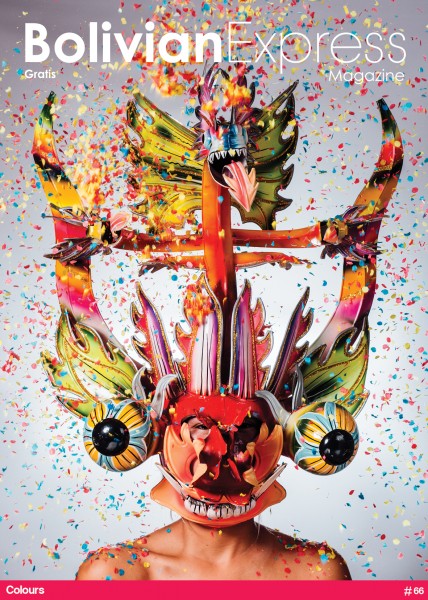

In this issue of Bolivian Express, we were inspired by these breathtaking moments, which so many of us have experienced living and working here. In day and night, colour takes on special meanings in Bolivia. From the grand swaths of purity in Sucre, Bolivia’s White City, to the rainbows of colors on towering murals breaking the greys and browns in the far reaches of El Alto, colours here continuously surprise. We see them in the blackened fingers and dark clothing of La Paz’s masked lustrabotas, and in the painted faces of its all-too-lovable clowns. And perhaps most notably, the artisans of Bolivia deploy colors to imbue specific meanings in their works, from elaborate, handmade textiles to ostentatious masks and costumes used in traditional dance. And with all the activity throughout the country, from the millions of people here living lives and changing its landscapes to the swaths of tourists visiting its incredible sites year after year, it is people who certainly bring the most colour to Bolivia.

My frequent nighttime rides down into La Paz will always be my strongest association with colour in Bolivia, but this country’s many shades and hues continue to enrich life here. Wherever one wanders, the colours are the first details to note. They contain secrets that can unlock so much of the mystery here, waiting to be understood. But for me, whether I have been gone for two days or two years, that hazy golden ride down the ridge from El Alto to La Paz conjures wonderful feelings inside me. And it reminds me of why I call this place home.

Illustration: Alexandra Meléan

Saturnino Ibañez and the face of Bolivian folklore

Calle Los Andes is a hidden gem of La Paz. Located just off Avenida Buenos Aires, this colourful incline will take you on a whistle-stop tour of Bolivian folklore. All of the outfits and accessories you may see during a traditional parade are condensed into this hefty hill. Between traditional dress and the odd gorilla costume, however, you will find the talleres of artisanal mask makers, who cut, mould and solder the main attractions of Bolivian folklore.

In one particular workshop, 73-year-old Saturnino Ibañez Paredes has been making masks for over fifty years. He is the maestro of all maestros. 'Young, right?' he jokes. The front room of his workshop is dizzying to the eye. Piles of masks and materials cover the walls, leaving a slim walkway to where his son is preparing a mask. Starting out as an ayudante himself, Ibañez worked for thirteen years to learn the tricks of the trade and become a maestro.

A single mask will take four days to make, with a day of preparation using moulds to cut the metal. 'You can't do anything without a mould,' Ibañez says. 'Every mask has a set of moulds, and there are many types of masks, all with a name and a dance.' Picking up a mask, he describes how ten different moulds are needed to make the characteristic features of a moreno mask: bulging eyes, an oversized panting tongue, and a pipe hanging from the mouth. The mask represents the African men that the Spanish took as slaves. It is worn in a dance called the Morenada, to mock the Spanish.

Hundreds of men in these masks dance in troupes at the big festivals, such as La Paz’s Gran Poder, where folkloristas like Ibañez most thrive. From mask makers and boot makers to musicians and locals selling food, artisans live for these national festivities. 'Everyone brings money to Gran Poder,' Ibañez explains, reminiscing about how he would spend his savings there in his youth. 'People come from all over the world to dance the Morenada. Americans, Japanese, French, Chinese – everyone dances here.' People come to Bolivia, rent a tiendita, integrate into Bolivian life and learn the dances. 'Bolivians, we are not selfish,’ he points out. ‘If someone wants to dance, go ahead. It doesn't bother us at all!'

The modern world of migration and globalisation has spread Bolivian folklore all over the world. Bolivians living abroad want to celebrate their culture through these traditional dances and they want to wear Ibañez' masks to do so. Just as appreciation for Bolivian folklore is traversing national borders, it breaking the boundaries of local generations. According to Ibañez, the change began about ten years ago, when more youths began to take part in the dances.

'Folklore is growing,' Ibañez claims. 'It will never fall.' As new generations join the trade and methods and materials change over time, so do the designs. 'There is no school where you can study these designs,' he explains. Ibañez learnt his trade from his maestro, as his juniors will from him. 'I design the masks myself, de mi computadora,' he jokes, pointing to his head.

Suddenly, he blows a whistle that scares the life out of me – and then again. Ibañez laughs. He is testing the whistle to sell it to a customer waiting outside his shop. 'Did that frighten you?' he chuckles sitting back down. 'What else...?’ he asks, as he roams from one piece of folklore to another among the piles that surround us. Then he focuses again. Taking a deeply genuine tone he says, 'I am the proudest man in the world. I am the only one who makes such good masks.'

'Folklore is nothing without a mask. You are nothing without a head.' Saturnino Ibañez

Ibañez is humble. Like a true artist, he lives through his art. 'It is a beautiful job. Thanks to this trade I now have a house and children,' he says.

'Folklore is nothing without a mask,’ he continues. ‘You are nothing without a head,' he says, grinning. This folklorista cares about what he makes, but above all he cares for the people around him – from his family to the safety of drunken festival-goers. Working with other artisans, he has managed to ban costume materials, such as tinsel and rope, that can become hazardous during the festival’s celebrations. To him, 'folklore is entertainment, nothing more.' But it is artists like Ibañez that keep this entertainment alive. After all: 'Who doesn't like to dance a Morenada?'

The Travellers Passing Through Bolivia and What They See

There are always people passing through here. Travellers trickle down through the Peruvian mountains, backpack up from Argentina, or emerge from the Amazonian rainforest. The foreign faces come and go, they have many more miles to cover, a continent still to see; Bolivia is often just a brief stop. Unlike in many of this country’s neighbours, for some here the sight of visitors is still a strange one, these distant people who have journeyed thousands of miles from their own homes to stand under a curious local gaze. Yet as international tourism only continues to increase across South America, perhaps it is worth asking: What do these strangers see when they look back at Bolivia?

What do these strangers see when they look back at Bolivia?

I am working in a quiet hostel in the center of Cochabamba, Jaguar House. Guests don’t usually stay long, maybe a few days. But skip them and you potentially miss a story that spans across countries and oceans. After the 2012 Olympics in London, Keith Banbury arrived in India at the start of his travels, having quit his job and dropped his few remaining commitments. Three continents and four years later, he’s still going. He’s volunteered for a month in the jungle; had all his valuables stolen in Argentina; and has eaten, as far as he’s concerned, an ungodly amount rice and chicken in South America.

His reasons for this global odyssey, however, are really quite simple. ‘I don’t want to be carrying a backpack when I’m 70,’ Keith said. Tall and thin, his concerns are certainly legitimate: his backpack is nearly twice his size. Yet this specter of old age reared up in the motivations of all I spoke to, whether they were in their mid-40s like Keith, or barely into their 20s. Seigfried Fuchs, a young German man travelling with his Irish girlfriend Rebecca Caulfield, had the same thing to say: ‘Better do it when you’re young than when you’re old with a stick in your hand.’ Broad-shouldered and confident, it’s hard to imagine he’ll ever need one.

These folks are certainly more than holiday goers; they are on a journey that demands something of the invincibility of youth. Jeffrey Plume, an easygoing American from Missouri, anecdotally described with considerable relish the chaos of his hostel in Cusco, from the in-house cocaine dealer doubling up as a male stripper to the backpacker pregnant from her ayahuasca shaman. ‘I meet a lot of crazy people,’ he said.

There is also a sense of intense forward motion in this place, of moving away not just from previous places but also from earlier selves. Silja Studóttir, an arts graduate from Iceland, had good reasons to leave home. Slight, ethereal, and almost fairy-like, she has the kind of blue eyes and long blond hair that comes only from Northern Europe. She travelled to leave her small island and an abusive relationship behind far behind her. ‘The word for stupid in Icelandic means “if you’re always at home”,’ she said. ‘That’s the reason I want to travel. I don’t want to be stupid in that sense.’

Some left even more at home when they decided to head south. Jeffrey is a PhD graduate in neuroscience and had a burgeoning career in the field. Dissatisfied and impatient, he quit his job, sold pretty much everything, and got on a plane to Latin America. Whilst waiting for his connecting flight in Miami, a fellow passenger asked why on earth he wanted to leave; after all, the United States has mountains and beaches, – why travel so far? ‘You don’t get it, it’s different,’ Jeffrey he told the man.

It is this difference that so captivates the people passing through here, something Rebecca and Seigfried were very clear on. They had spent a year working in Australia together, and as far as Seifgried was concerned, ‘They are spoilt there.’ It felt to them like a poor mimicry of somewhere else, a bland combination of other places. In comparison, Rebecca said, ‘There is so much history, culture in South America.’ Of course, there is always surprise at how varied Bolivia is compared to its neighbours. Travelling overnight from La Paz to Jaguar House, Sija described it as taking ‘a bus back in time’, waking up to find clerks in the bus station using typewriters. In turn, faced by the tall banking towers along Cochabamba’s El Prado, Jeffrey felt like he was back in glossy concrete sheen of Miami.

For these visitors, just as hard to pin down are the local people themselves. How long does it take to understand the people of a country? A month? A lifetime? If there was ‘hesitancy’, as Jeffrey put it, in those he met, this was overshadowed by the plethora of stories these new people had to tell, usually on an overnight bus ride. On his way up to Rurrenabaque, he got into a long discussion with some government officials who alluded to a secretive mission they refused to fully disclose. Keith chatted with a relative of a restaurant owner who was famous, so he claimed, for owning the only vegetarian restaurant in Potosí. The man extended a casual invitation for Keith to visit and a month later he actually arrived at the Manzana Mágico. ‘I think he was surprised that I really turned up,’ Keith said, although that didn’t stop the man giving him a full tour of the city.

‘I don’t want to be carrying a backpack when I’m 70.’

—Keith Banbury

It is these stories of connection and involvement that the people I met seemed to enjoy talking about most. In one regard, there is a profound disconnection expressed by these travellers, from the places they left behind to the items they brought with them. ‘I don’t have anything which is irreplaceable; they’re just things, you know, things you carry around,’ Keith said. ‘You can just move on.’ Few I spoke to had come to stay in Bolivia specifically; they had just ended up here, or were only passing through. Yet to travel thousands of miles, to leave boring jobs or difficult relationships behind, is to seek something more than a nice photo. Perhaps it is in search of a place to belong.

Photo: William Wroblewski

A One-Sided Love Affair That Was Never Meant to Last

I cannot really explain how this love came to be. What I can tell you is the story of how we met and let you decide it for yourself.

That day, I wasn’t looking to fall in love. I was tasked with interviewing a clown for this publication, a clown that does not speak but only communicates in squeaks and whistles. I was told his name was Edgar but goes by Garo, that he was 27 years old, and that for the last three years he’s been busking on the corner of Sagarnaga and El Prado nearly every night. I heard that he loved to get the audience involved in his routine, and that each performance was a crazy mixture of pantomime and acrobatics. He apparently channelled his inner child, mocking unsuspecting passersby and harassing vehicles stopped in traffic.

I set out to find him and to ask him the usual questions: Do clowns get sad sometime? Does it bother them that they are often feared? Do their painted faces disguise constant pain and sorrow? You know, questions of that nature.

When I got to Sagarnaga, I heard him from across the square. We made eye contact, and I felt my heart flutter. He squeaked something that sounded vaguely familiar but escaped my understanding. I’m pretty sure it was ‘I love you, marry me, let’s start a family’ – but like I said, it was a bit squeaky and unclear.

We don’t pick the people we fall in love with, and while I never planned to love a clown, this is exactly what happened. Many of us fall for clowns, but mine just happens to be the kind that paints his face and wears bright, patchy outfits.

We don’t pick the people we fall in love with, and I never planned to love a clown.

He went back to entertaining the crowd and I was drawn to his confidence and the love he exhibited for his craft – things I really respect in a man. During his break, he ran up to me and squeaked in my face – how bright and promising our future seemed at that time!

Now, I am not a naïve little girl, but I know that any woman would consider herself lucky to be loved by this clown. Knowing that there are very few, if any, female clowns working the area, I asked him what he liked in a woman. Based on all the women he hit on and whistled at, I would say he seems like to women in short skirts, women holding babies, women carrying large sacks on their backs, women who are walking quickly, women who are walking slowly, women over 50, women under 50, women on their cell phones, and women with men on their arms. This clown did not discriminate, which just goes to prove the purity of his heart. Clearly I had a chance with this clown, and would just have to learn how to communicate it to him, so the following day I put on my best face and headed out to find him.

I won’t lie to you and say it was easy when I found him making eye contact and whistling at another woman that harrowing next day. Now the squeaks that used to make my heart flip only serve to haunt me as I walk the lonely streets of La Paz. I think about how I could have been the woman who finally made him speak his first words. I think about the man who made me laugh – a man of few words and many squeaks who seemed to understand me better than any other. I think about him daily, but most nights I just end up in tears, watching my makeup run in the mirror.

Most nights I just end up in tears, watching my makeup run in the mirror.

Like in most relationships, I guess there was some miscommunication – maybe I misread the signs, I can admit that now. I thought I spoke Spanish, but maybe not his squeaky dialect? This is something my therapist is still trying to unravel.

He’s really cute actually, my therapist. I really do think he cares about me in a special way. Whenever we make eye contact, his brown eyes kind of sparkle.

Download

Download