In this section you will find English translations to some of the Spanish, Aymara and Quechua terms used in our articles.

Feel free to contribute to this page with your own definitions in the comments section.

Aguas vertientes: Spring Waters

Ajayu: Soul, Spirits

Altéños: Citizens of El Alto

Altiplano: The Andean high plateau extending through the western region of Bolivia

Ají: Local term for combination of spices and hot peppers from the Capsicum family. Can be ground dry or prepared in a paste

Anticuchos: Sliced and skewered beef hearts, a traditional late-night meal in the Andes, typically served with potatoes and a spicy peanut aji

Anticuchera: Seller of skewered and thinly-sliced cow hearts

Aptaphi: Andean buffet. It is a meal collected and shared in community, being it a group of friends, family or a larger organization

Aruskipasipxañanaka: ‘It is my personal knowledge that it is necessary for all of us, including you, to make the effort to communicate’

Ayllu: Political, social, economic, and administrative unit of the Andes

Bolsita: ‘little bag’, a common term to denote the soft plastic bags in which drinks are sold across the city.

Bulto: Bundle

Camba: Colloquial term for someone from the eastern lowlands of Bolivia, more specifically from Santa Cruz

Campesino: Working native of a rural area

Campo: Countryside

Centavo: Cent

Ch’alla: Traditional ritual to bless a place

Chicha: A drink made out of corn

Chifa: Chines restauran

Chiflera: Women who sell medicinal herbs

Chiwiña: Aymara word for ‘meeting place’

Chola: Indigenous woman in traditional dress and bowler hat

Cholita: Affectionate diminutive for chola

Chuño: Freeze-dried product obtained by exposing a variety of potatoes to very low night tempera- tures, freezing them, and subsequently expos- ing them to the intense sunlight of the day

Chuyma: Aymara word for heart

Copa América: A football tournament held every four years in which 12 national teams from across South America come head to head

Comida rápida: Fast food

Crema de leche: Cream skimmed from milk

Criollo: Used in Colonial times to denote a person born in South America from European parents

Dinero: Money

Estatua viviente: Living statue

Extranjero/a: Foreigner

Extraño/a: Strange

Fácil: Easy

Farmacia: Pharmacy

Feria 16 de julio: El Alto Market, said to be the largest fleamarket in South America

Fiesta: Celebration

Gota de leche: Drop of milk

Guapa: Term used to refer to an attractive woman

Guato/huato/wato: Colloquial term for shoelace

Hermana: Sister

Hogares de niños: Orphanage

Huayño: Melancholy rhythm played using wind instruments, popular across the the Andean

Huevitos: Small eggs

Indigenista catarista: An activist for indigenous culture

Indio: Pejorative term to refer to socio-ethnic indigenous people, sometimes appropriated by indigenistas

Institutos: Educational institutes (in the context of the piece)

Islas flotantes: Floating islands

Joven: Young men

Kallawaya: Traditional healer

K’ehua: Aymara word describing neither man nor woman

Kullawada: An Aymara traditional dance

Lancha: Motor boat

Llajwa: Spicy Bolivian sauce

Loco: Crazy

Lunes: Monday

Lustrabotas: Shoeshine boy or girl

Mallku: Meaning condor, it is the name given to community leaders in Aymara societies

Mate de coca: Coca tea

Matrimonio: Wedding

Mesero: Waiter

Micro: Bus

Morenada: Afro-Bolivian music from the Andes

Munaña (Querer), Waylluña (Amar): Love. In Spanish, there is a difference between Querer which is ‘To want’ and the stronger term Amar ‘To love’

Paceño/a: Of or relating to the city of La Paz

Pachakuti: Time/space upheaval

Pajpakus: Derived from the quechua word for owl, it is the name given to wandering salesmen renowned for their oratory skills

Parche natural: A natural herb paste

Personaje: Character

Pesq'e con leche y ahogado: Quinoa based dish with milk and a rich and spicy sauce

Pijcheo: The ceremonial chewing of coca leaves

Pollera: Long, flowing one-piece skirts, sometimes embroidered, worn by cholitas

Pongo: Indigenous domestic servant

Preste: Big party offered normally by a wealthy member of a community, most of the time it is part of a larger celebration such as Gran Poder festival

Productores: Reproducers

Puertita: Small door

Rebaja: Discount

Salto: Jump

Servir: Servirse is a colloquial expression in Spanish which refers to the act of someone helping themselves to something

Sonrisa: Smile

Sirwiñaku: Probation period before marriage in which the bride-to-be lives for some time in the house of her in-laws

Talleres: Workshop

Tarijeños: From the city of Tarija

Taxista: Taxi driver

Toma: Take

Totora: A reed found in Lake Titicaca, used to build the floating islands

Uña de gato: Woody vine found in the jungle used to cure diseases such as cancer

Valle: Valley

Wawa: Aymara term for baby or small child

Willakuti: 'Return of the sun,' in Aymara

Yapa: Bonus goods obtained from a seller a part of the haggling process

Yatiri: Traditional healer

A celebration of identity and culture on the salt flats

Extending its reach beyond the sacred site of Tiwanaku, in 2013 the government has decided to hold further celebrations for the Aymara New Year in El Salar de Uyuni. In a move that transforms the touristic into sacred, tradition thus continues to be reinvented.

Photo: Alexandra Meleán

Blood stains the pearly, white ground of the Uyuni salt flats, flowing from the necks of two decapitated llamas. Coca leaves adorn the fur of the two, as they lie bound and gagged, fatally compromised in a sacrifice to la Pachamama (Mother Earth).

I haphazardly scramble up Isla Jithik’sa, a sharp, crumbly rock mass about the size of a carnival cruise ship. From the top, I have a bird’s eye view of a government-organized festival held in honor of Willakuti .

Rumour has it that President Evo Morales will be here. Upon leaving La Paz, it is still unclear if he would choose Uyuni over Tiwanaku for the New Year’s celebration. Traditionally, Tiwanaku has been the stage for this momentous occasion due to its archaeological status as a sacred site at the root of Andean culture.

Maybe he’ll be here. And if he shows up, maybe he’ll say a thing or two about the future of Bolivia’s national treasure, its lithium. Perhaps he’ll talk about international trade.

Over the salt flats, a dreamy pink horizon tints the sky. In the north, the sun rises, marking the beginning of the winter solstice. Music, dance and ritual follow.

Sunlight illuminates the Andean Mountains. An Aymaran priest lights a fire at the top of Isla Jithik’sa. The burning kindle is an offering to Tatainti. '¡Jallalla!' he says, and everyone follows.

Evo Morales does not show up, but his daughter Eva does. In keeping with an Aymara ritual, she pours alcohol onto the fur of the two llamas and takes a swig from the same bottle. Later, I walk up to her, kiss her cheek and shake her hand. She tells me Andean traditions can be preserved.

'Young people must come to events like these,’ she says. ‘They should share more of their lives with our indigenous people’.

Quickly, the mood turns overtly political. In a matter of seconds, the salt flats become a stage, a cultural platform representing Bolivia’s plurinational identity. As of 2009, the Bolivian constitution states the country is, 'founded in decolonization, without discrimination or exploitation'. Cultural rediscovery unifies the 36 indigenous communities in Bolivia that demand adequate representation.

'The Plurinational State of Bolivia, has to include all of our indigenous communities,' says indigenous leader Pascual Topo de Villaroel, ' like in the times of Tawantinsuyuo and Qollasuyu. Otherwise the Plurinational State of Bolivia does not exist'.

I stare at a framed portrait of Tupac Amaru, the last Incan emperor before the Spanish colonized Bolivia, which lies at Villaroel’s feet.

Felix Cardenas, Vice Minister for Decolonization proclaims, 'we have been submissive to other traditions for a long time, but today is the Andean and Amazonian New Year. Thanks to our President we can keep moving forward toward better conditions in our country.'

In the distance, the national Bolivian flag blows softly in the wind next to the national Wiphala flag. Felix and Eva dance to the sound of Andean drums and panflutes. In the rich salt flats of Bolivia, a new agricultural year begins for the indigenous Aymara nation.

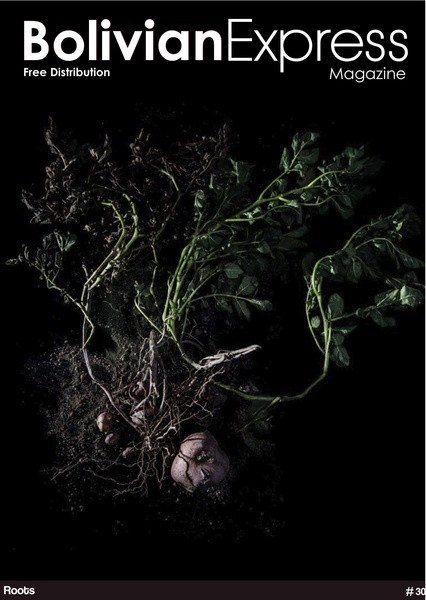

In Bolivia, culture, civilization, and the Andean market economy revolve around the cultivation of the potato.

Photo: Juan Manuel Lobaton

‘All of the greatest cultures and civilizations have been built around a lake or a sustainable river’, argues Alexis Pérez, my Latin American History Professor. This is certainly the case for many villages built around Lake Titicaca —such as the Tihuanacota, Chiripa or Aymara—which also share the commonality of growing a crop which has mythic significance: the potato.

The origins of the potato crop began around 8,000 years ago near Lake Titicaca. Several thousands of years earlier, communities of hunters and gatherers populated the south of the continent. Potato plants grew in abundance in the fields around the lake, even before the settlement of the first communities.

Native stories about the potato’s origin are varied and involve everything from illas and chullpas to condor societies, or versions involving toads, foxes, and of course the lake, around which extraordinary tales take place. Cultivation of the potato has not only determined the agricultural calendar in the Andean world, but its production has been tied to the Andean cosmovision, as well as to the Pachamama, linking it with the fertility of the land and the people.

The cultivation of potatoes requires rotation and rest. That is to say, their successful harvest depends on the quantity and frequency of rain, as well as an appropriate period for the land to rest. It’s indeed possible this very practice gave origin and sense to the rotation of Mallkus , as well as to the Ayllu system.

When the colonisers arrived, work on the land owned by the community in the Ayllu began to deteriorate, and the Spanish policy of the encomienda was established, producing serious damage to the social organisation of the Andean world. This schism destabilised local spatial relations, with an ensuing weakening of the ecological organisation. The destruction of the Ayllu generated total confusion in the Andean villages.

During the Republic, different reforms were implemented. The most transcendental changes took place in 1953 after a revolution which shook the socioeconomic order of the country. The revolutionary project aimed towards indigenous civilization through processes of ‘mestización’ (hybridization), ‘castellanizacion’ (spreading of the spanish language as a lingua franca), and the parcelling off of rural land. Many traditional values were transformed in the process. The market economy took over and came to govern the production of potatoes in the Andes. This brought about a peculiarly hybrid situation, a communitarian system working on parcelled land, and subject to market commercialisation.

The subsistence of Andean population has historically relied on the cultivation of this crop. Low estimates posit that 200 varieties have been domesticated, and according to research put together during the international year of the potato in 2008, there could be as many as 5000 varieties produced in over 100 countries. According to the Institute for the Development of Rural America (IP- DRS), today the potato is the third most important crop in the human diet, after rice and wheat.

After the colonial era and successive waves of European migration, the potato reached all corners of the world. Sailors and governors of colonies were among the first to appreciate importance of this tuber, as it fed them during long journeys. Missionaries and colonisers spread the cultivation of potato to all continents, which is how it landed in Europe and Africa in the 16th Century, followed by Asia and North America in the 17th Century, and continuing on to Australia and Oceania in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

In global terms, China is currently the largest grower of potatoes, followed by Russia, India and the United States. According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), 325 million tonnes of potatoes are produced each year. The world’s demand is now only owed to its nutritional properties (being a great source of calories, micro- nutrients and proteins), but due to its uses in medicine, the production of textiles and paper, as well as applications in pharmaceutical, mining and oil industries.

In Bolivia, it is not surprising to find the potato present in a large proportion of national dishes. Without her, life would be more difficult in the Andean world. No Andean family will lack potato or its derivatives such as tunta or chuño. Neither can it be absent from parties, social or public events. I ask myself, would there be an apthapi without potato? I don’t think so.

This is why the significance of the potato goes beyond its importance in the origin of Andean societies. It has been instrumental in feeding humanity as a whole. Paradoxically, colonisation allowed the potato to colonise the world, becoming one of the true legacies left by the journey Columbus embarked upon in 1492. Over five centuries later, the true riches weren’t to be found in the gold which colonisers so recklessly sought. The true, renewable wealth of the land was to be found underneath the earth and initially hidden to their eyes: the potato.

Translated from the Spanish by Alexandra Meleán

Download

Download