Travelling 20,000 km from the Philippines, Ryle Lagonsin arrives in Bolivia to find chilling parallels between the countries’ regionalism and identity crises. Can either set of nations disentangle their convoluted histories and prejudices to act affirmatively as a cohesive whole?

Illustration: Gielizza Marie Calzado

I am Filipino. When I leave my country for another one, my passport will always say I am Filipino. But within the Philippines, I am Tagalog. I am not Bisaya nor Kapampangan. Within my country, I am someone else. I have a specific identity.

But what does identity even mean? I can imagine Bolivianos, inside the country and out, asking themselves this same question.

For the last two months, Bolivia has become my temporary home; La Paz, specifically. And although at first, it felt as if I had hurled myself from one extreme to another, I have become quite used to this new environment. So much so, that it no longer feels like a completely foreign world to me. Because inasmuch as landlocked Bolivia contrasts the archipelagic Philippines, I have come to realize that these two countries share a resemblance deep beyond their stark physical differences.

A rich indigenous heritage, a long history under Spanish rule, a blessed and cursed wealth of extractable resources: these are obvious similarities that could be noticed by anyone who has ever been to, or at the very least read about, both countries. Along with these, one could also say they share political and economic instability and, as probably known by more people, a lingering third world status.

However, none of these pertain to the kind of resemblance that has caught my attention. What I really mean by the word is a face: the shared face of an identity crisis.

Just recently, I went on a city tour of Bolivia's famous White City, Sucre. Wanting to impress my guide, I remember saying something along the lines of 'Bolivians are all called Paceños, right?'. Ignorant assumption, apparently.

'No, I am definitely not Paceña ! I am Sucrense!', was her response. Let me clarify, it was not said as severely as it looks like in print. The response was, in fact, followed by an I-understand-you're-a-tourist kind of laugh.

Whether and how much she took offense, I would not know. She did warn me other people, specifically cambas , could take such a statement very seriously. Why? Historical rifts, stereotypes, government favoritism—the list goes on. The bottom line is that many Bolivians just don't want to be associated with other Bolivian groups.

The revelations from that day felt both interestingly and disturbingly familiar. Interesting, because of the stories my guide told me, especially surrounding the lingering bitterness between Sucre and La Paz (over where the government seat of power is located). That one sounded a lot like the history of Cebu and Manila, two important places in my country. Disturbing, because of her firm declaration that she was not Paceña, but Sucrense. That one sounded a lot like hearing a Tagalog firmly denying being a Bisaya. In fact, that one could have sounded a lot like hearing myself speak.

Why is this such a big deal to us, Filipinos and Bolivianos? Why is it so necessary for us to point out which group we belong to and disassociate ourselves from the rest, who are nonetheless of the same nationality?

One just needs to watch a YouTube video of some Fil-Am singer giving a good audition on American Idol, spurring thousands of comments that repeat the words 'Pinoy (Filipino) Pride!' Or observe how an international Club Bolívar win rouses the entire country to proclaim 'Viva Bolivia!'

Yet, mistake a Quechua for an Aymara and watch them take it as an insult. And don't even think about straying from the posh Metro Manila accent if you don't want to be the butt of jokes.

It is a fascinatingly ironic, and ultimately disappointing, mindset how people from these countries project a solid national union only in times of supposed pride in front of foreigners, but crumble to their own factions within their own borders.

It would be pointless to blame the diversity of peoples in both Bolivia and the Philippines, but it cannot be denied either that with so many different customs, beliefs, and ways of thinking; disagreements and prejudiced conditioning are bound to happen.

Should this issue of lineage be reduced to a binary of inferiority or of superiority? White skin, light-colored eyes, and foreign accents—this is no less of a recipe for instant celebrity in the Philippines as it is in Bolivia. And, consciously or unconsciously, we all play a role in reproducing these biases.

Perhaps I have had the slightest privilege of personally seeing two sides of the world confronting the same social sickness. But as I said, its manifestation in both places is uncanny. For this reason, it is not hard for me to imagine the questions in my mind running within that of an ordinary Boliviano as well.

I am sure it would take long before either of us find a proper definition to our dubious ‘identities’. But for now, I say I am Filipino. And by me, this is to acknowledge that I am Tagalog, I am Bisaya, I am Kapampangan, I am of every indigenous Filipino group. I hope my Boliviano brother, too, would accept being every Boliviano as the answer to his own identity questions.

Setting Down Oriental Roots in the Andes

Photo: Michael Dunn Caceres

What does it mean to be Bolivian? Does it require listening to Morenadas , eating salteñas; and drinking Paceña ? Does one have to have Bolivian blood in their veins, Bolivian roots in their lineage?

There is no an exact answer to that question since many Bolivians have different views of what being Bolivian is. Many people would argue that what truly makes a person Bolivian is the desire to feel like one. After all, people cannot embrace the traditions of the country’s culture if they do not see themselves as Bolivians in the first place.

This is the case of Lu Qing, a 50-year-old Chinese immigrant who, even though she was born in China, considers herself to be very paceña—simply because she feels like one.

Lu Qing’s story is full of adventure, with failure and success in equal measures. It’s representative, too, of stories of many Chinese immigrants who end up in Bolivia and consider themselves to be Bolivians with Asian roots.

Many Chinese immigrants first established communities in Bolivia during the late twentieth century. Job opportunities in mining and agriculture attracted them to Bolivia with the promise of a better life. As a result, Chinese immigrants settled in Bolivia and created a new home for themselves far away from their native country.

But unlike other countries in Latin America, Bolivia has received a relatively small number of Chinese immigrants. Peru, for example, has the largest population of Chinese migrants in Latin America, with some estimates of there being over 4 million Peruvians with Chinese ancestry.

In Bolivia, the number of Chinese immigrants is drastically lower. During the 1990s, there were just 500 Chinese immigrants officially living in Bolivia, and by 2001 the number increased only by a hundred.

‘It has been sixteen years since I arrived from China’, Lu Qing declared with a nervous smile and a candid look in the comfort of her beautiful classic looking Chinese restaurant located on Avenida 20 de Octubre in Sopocachi, La Paz.

Lu Qing decided to come to Bolivia with her family in 1997 to find work. She was 34. Her husband and uncle had bought some land in Bolivia, on which they wanted to develop a gold mine. But right after they arrived, her husband lost all the money he had invested in the mine. ‘It was very hard for my family’, Lu Qing says.

However, Lu Qing and her husband dusted themselves off and decided to open a Chinese restaurant—or, as they’re known in Bolivia and Peru, a chifa . 'I needed to pay for the education of my child,' she says. ‘I needed to survive, so I worked hard to open a chifa’.

The word chifa emerged in Peru during the 1930s. Originally from the Cantonese language, it means ‘eat rice’. The popularity of chifas increased enormously during the nineteenth century, and later became part of the culinary tradition of Peru. As a result, the term became popular in other parts of Latin America.

Chifas in Bolivia serve a variety of dishes that contain noodles, rice, seafood and meat, just as any other Chinese restaurant. However, Bolivian traditions are mixed in. For example, minced rocoto pepper usually accompanies the soy sauce in Bolivian chifas, and typical Bolivian drinks, such as mate de coca and chicha , are served.

After much work and effort, Lu Qing and her family made it through some very difficult times, but eventually were able run a successful chifa.

‘It was my Chinese roots that allowed my business to become successful’, Lu Qing says. She points to the fact that she grew up in China, where she was taught from a young age to be disciplined and punctual. She considers those qualities to be extremely important for everything she has achieved.

‘My chifa always does well because it is punctual. It serves food of quality and it has a responsible staff’, she says. ‘I could not have done it otherwise.’

Although Lu Qing’s Chinese roots are an important aspect of her life because they represent who she is, living in La Paz for so long has influenced her too. ‘I love the food and music from Bolivia’, she says with excitement. ‘I learned to speak Spanish in Bolivia, and I have so many Bolivian friends that I feel Bolivian.’

Lu Qing believes that her personal attention and interaction with her customers is fundamental to the prosperity of her business. ‘I am a people’s person’, she reveals.

Because Lu Qing decided to adopt the Bolivian culture as her own, instead of looking at it as foreign, it made her new life in Bolivia easier, and it allowed her to assimilate into Bolivian society rapidly. ‘I like to learn about the Bolivian culture because Bolivia is my home’, she says. ‘It is the place where I live now.’

But the adoption of a new culture in Bolivia can also run the other way. The presence of Chinese people in La Paz has also motivated some Bolivians to adopt certain cultural aspects of the Chinese. ‘Many Bolivian people like Chinese culture’, Lu Qing says. ‘Many of my clients like to practice tai chi, because it is good for the health, and others love to drink Chinese tea.’

The Chinese language itself is also becoming increasingly popular. ‘Many students study Chinese in the schools and universities regularly now’, Li Qing says.

Looking at the small world that Lu Qing has build in La Paz for her and her family, it can be seen that many Chinese immigrants to Bolivia have created a new life far from home by adopting Bolivian culture.

However, in their quest, they had not forgotten their own roots; instead, they seek to integrate them within the Bolivian culture in order break racial stereotypes and create an alliance that can improve the relationship between the Chinese and the Bolivian communities.

While consumers have become more and more conscious, producers are fighting to manifest this consciousness in the food they produce. Traditional production techniques are simple, and agriculture just isn’t simple anymore. Nevertheless, groups have sprouted all over La Paz that seek honest food and aim to consume consciously.

Upon exploring La Paz, it becomes apparent that definitions of conscious eating and humane production here are as diverse as Bolivia itself. In a country where the fruits and vegetables colour the streets, and cows that graze in the nearby mountains are being stuffed into Tucumanas days later, it would be expected that agricultural and consumption perspectives around conscious food differ greatly from the highly transgenic, yet veg-enthusiast United States.

As a vegetarian, I have always sought out soy products, whose meatless goodness made being vegetarian both easier and more enjoyable. Being told that vegetarianism is close to nonexistent in Bolivia, I was pleasantly surprised to see plenty of soya products and meatless options at food shops. In the United States, soy is widely produced and perceived to be the Dorothy to meat’s Wicked Witch From the West.

Soy, however, is not all it’s cracked up to be. Bolivia has made me scrutinize soy as a transgenic product that causes damage to the Pachamama (Mother Earth), whose rights Bolivians are now constitutionally compelled to respect.

Pachamama Transgénica

A transgenic is a genetically modified organism, a living thing, such as a plant, to which a new gene has been introduced, resulting in a change of its genetic makeup. This gene could be that of another plant or even another animal. Don’t be irked; your vegetables don’t have eyes.

For example, DNA is extracted from an organism, such as a tomato. A gene is likewise extracted from the other organism in the form of the desired protein to implant into the tomato. The tomato gene is modified and fragmented, and a piece is then replaced with one from the new organism. In laymen’s terms, genetic modification creates organisms that cannot be obtained in nature. It creates plants that are super resistant to weather, larger and more numerous. They’re super plants.

Article 255 of the Bolivian Constitution prohibits the production, importation and commercialisation of GM foods. A set of laws reiterates this principle. The law specifically prohibits the introduction of packages that involve genetically modified seeds for a product that grows native to Bolivia. If non-native crops are introduced to Bolivia, such as soy, rice, tomatoes, cotton, corn, there will be standards established for their production. In 2005, Resolution Nº 135/05 freed maize from any possibility of transgenic contamination. In 2009, Supreme Decree 181 (art. 80) prohibited the State from purchasing GM foods, and bans their use as part of school meals. Similarly, the Law of Mother Earth establishes 'the right to preservation of the differentiation and variety of beings that make up Mother Earth', banning their genetic modification and any artificial modification of their structure. In its 24th article, this law further establishes the implementation of necessary measures for the gradual elimination of GM products from the country and its markets.

All of the above would make us reasonably believe that Bolivia is safely protected from any GM presence on its soil or in its domestic market. Yet according to TUNUPA, an informational magazine from Fundacion Solón, in 2010 Bolivian land contained 0.9 million hectares of transgenic soy, ranking it as the 11th country in terms of transgenic crop production, and placing it in the category of 'mega-producer', despite its status as a developing country.

Sources close to the Vice-Minister of Rural Development deny the above data, although admitting to the possibility of insignificant amounts existing in Bolivian markets.

In the first week of June, the Bolivian government announced the importation of flour from the US, prompting broad speculation of this flour being genetically modified. Yet the government sustains that it comes from corporations that work with such crops. The mystery still remains.

Crops as Leeches

Truth is, genetically modified crops have not been proven to do significant harm to humans (though they do in mice, which seem to develop tumors from anything if administered in excess). The most prominent worry is that the implanted gene may be a hidden allergen to the consumer. Conversely, transgenic plants have been known to boost nutritional value in some foodstuffs.

According to researcher Manuel Morales Álvarez, the issue is not that transgenic food is unlabeled, but rather that the most significant harm this food does occurs before it hits the shelves. Homogenising the land that is naturally diverse harms the biodiversity that helps plants grow naturally in the first place, leaving the once fertile Pachamama depleted and useless.

The law seems to specifically protect Pachamama who, like a woman, cannot feed her children beyond what comes from her body. While those crops that are native to Bolivia, such as quinoa, chia, sesame and amaranth, are easily organically produced, crops such as soy that have been forcefully introduced have caused significant damage to the land. The cultivation of soy absorbs the fertility of the earth, and combined with the pesticides and fertilisers, makes the soil near useless. In Bolivia, 100,000 acres of land have been degraded due to soy.

Álvarez says that compared to other countries, Bolivian food products are not hugely genetically modified. Brazil and the United States shadow Bolivia as far as GM landmass is concerned, with 30 and 70 percent more hectares of transgenic crops, respectively, while Argentina follows closely behind. Over the past 30 years, around 80% of the South American continent has become involved in the production of soy, prompting Miguel Crespo from Probioma to consider this the creation of a 'Republica Soyera', a trans-border territory he calls a 'Soy Republic'.

In some ways, transgenic crops have helped farmers. According to Álvarez, the climate in Bolivia is so variable, and the soil often so unyielding, that a little modification in the plants’ genetic properties helps farmers by increasing the volume and quality of produce. However, farmers are inconvenienced by their newfound dependence on transgenic seeds, as the price has risen drastically. In 2007, the cost of cultivating one hectare of GM soy was $300, compared to $450 in 2012, a 50% increase.

The Instituto Boliviano de Comercio Exterior have voiced their concerns around this set of laws, claiming that transgenic crops should be allowed due to the economic necessity for exporters to remain competitive.

According to Enrique Castañon of Fundación Tierra, exporters of transgenic crops have been disproportionately affected by this law. This is because transgenic seeds are increasingly expensive to purchase, and continually more expensive to produce as some of farmers’ profits must go towards the source of these super seeds.

Transgenic means Outsourcing

Traditional farming techniques that define the country are being compromised due to external pressures. While farmers use their manual tools as quickly as they can to produce a high quality, organic product, neighbouring countries are reaping and packaging products that multiply as rapidly as bacteria.According to Miguel Crespo of Probioma, transgenics are deeply enmeshed in an international trade dynamic, resulting in extranjero

control over some Bolivian resources. He estimates that 80% of the resources used in soy production are imported from various countries, and that 66% of the production of soy in the hands of foreigners. Enrique Castañon at Fundación Tierra similarly believes that Bolivia is 'losing its food sovereignty'.

Traditional farming techniques that define the country are being compromised due to external pressures. While farmers use their manual tools as quickly as they can to produce a high quality, organic product, neighbouring countries are reaping and packaging products that multiply as rapidly as bacteria.

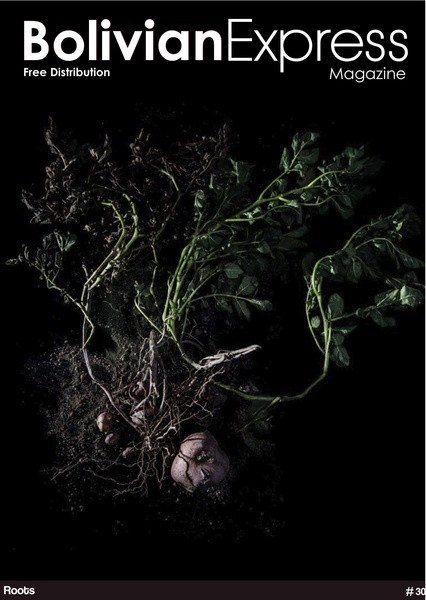

Keeping the Roots Alive

Paola Mejia is the manager of CABOLQUI, which has been working since 2005 to increase organic production of major products native to Bolivia. She said that while Quinoa, their major focus, is grown more or less easily using traditional techniques, many products, such as soy, are more difficult to grow without the help of chemicals and genetic modification.

'Organic production is very difficult, for us its almost impossible to see how we can work with organic soy because all of the variables against this organic standard.'

Mejía said that CABOLQUI has worked closely with the government to produce organic quinoa, at least. While the government supports all its statues in the production, exportation and distribution of quinoa, Mejía could not comment on the government’s work with soy and other potentially transgenic crops.

Mejía estimates that around 80% of quinoa production in Bolivia is currently organic, with 12% GM and the remainder in transition. According to Mejía, organic producers receive 25% more profit for their crops, as well as priceless health benefits as they avoid pesticides. Mejía said she predicts that in the future there will be an international standard for organic quinoa, stretching beyond Peru and Bolivia.

'Here in Bolivia there is a tradition to work in harmony with the soil, and the best way to do that is through organic production,' Mejía affirms. 'This is something that comes from hundreds of years ago, its not new for us.'

While working harmoniously with the soil is part of tradition, Mejía realises that maintaining tradition will not on its own bring food to the world’s tables. She lamented that there is no way for traditional techniques to provide for the international market, which has been ravenously demanding organic quinoa. For this reason, new organic production techniques are being sought.

'We are very committed to this organic standard, yet the only way to increase supply is by increasing yield of this system of production.'

External pressures from GMO monsters such as Monsanto have set the bar high, forcing countries to give into transgenic crops. According to information from TUNUPA, an informative publication from Fundación Solón, some have no choice but to buy transgenic seeds, or worse, they have no idea that their plants are modified. What can be done with artisanal tools is no longer sufficient, and Mother Nature is not producing quickly enough to supply a hungry world. Bolivians, organic is tradition; their goal is 'vivir bien'. Sadly, while organic is always a part of indigenous, what is indigenous is not always organic.

From the Fields to the Markets

Of the many markets in La Paz, the market called 20 de Enero runs Lunes

to Lunes in Chasquipampa, Zona Sur. These piles of fruits and vegetables are undoubtedly the herbivore’s dream. According to Marcela Poma, much of the produce simply leaves the farming region at the foothills of the Illimani to be sold at the market, she explains as she motions over her shoulder to the sun-drenched hills. The main purpose of the market is to cater to the surrounding community within a 15-mile radius.

But don’t be fooled by the romanticised image of unwrapped, unmarked piles of fruit and women draped in shawls carrying sacks of produce on their backs. Vendor Alicia Arteaga sat in front of her piles of fruit, weighing each piece with her eyes and pricing them for interested shoppers. I asked her if the fruit was organic.

'Claro,' she said confidently.

When I asked her if chemicals and pesticides were used in their production, to my surprise, she also replied affirmatively. When I finally asked her to define organic, she subtly started a conversation elsewhere, avoiding any further questions.

Consumption-conscious Communities

Although it becomes apparent that many locals have no concept of organic, the city has bloomed with organisations, stores and restaurants which share the goal of maintaining conscious forms of consumption, be it through abstaining from meat, transgenic products, or both. For many of these conscious communities, the objective is not simply for people to be conscious of their own health, but more broadly of the health of the environment.

Namas Té, a vegan restaurant, boasts 'the only vegetarian salteña in La Paz', while Tierra Sana, popular amongst foreigners and locals alike, offers a savory vegetarian lunch for two. While the menu at local vegetarian restaurants are completely meat-free, organic is not always guaranteed.

Centro Nutricional Ecologico opened on Calle Zolio Flores about ten years ago, and aims to sell whole wheat grain products, often infused with quinoa and soy. The products are entirely organic, and quite affordable as well.

'It’s very difficult to acquire organic wheat,' tells me Rosemary Tintaya Pacheco, who runs the store. 'The price of organic wheat has increased'. Pacheco recognises that her clients prefer to eat whole grains and organic produce. During our conversation she sells multiple bags of whole-wheat buns.

'It’s healthier to consume organic, it prevents sickness,' Pacheco said. While she isn’t vegetarian, she mainly eats vegetables—and always whole wheat. 'Not many people realize that transgenic food harms health', she adds.

On the same street, business owner Dominga Mamani has sold natural products sourced from the Andes since 2011. Surrounded by boxes of completely natural quinoa and grains, she said that the products go directly from the earth to the shelves.

However not all conscious eating efforts are grass-roots local initiatives. Herbalife is a California-based company which sells natural products and food supplements to customers in 88 countries, reporting net sales of over $4bn in 2012. Giselle Zuleta, a local saleswoman for the company, believes that, 'Everything that comes out of the ground should be natural,' Paradoxically, Giselle wasn’t sure if her product, imported from the US, was completely organic. She was only able to add, 'I don’t agree with chemicals being added'.

2013 is the International Year of Organic Food, a year for the growing community of food-conscious people to celebrate the movement that, according to Mirna Fernandez of the Laboratorio de Comida Consciente, has grown much over the past 7 years. 'Not only is it about eating vegetarian but also about asking where the food comes from,' she said. 'We are few, but we are growing.'

El Laboratorio para la Comida Consciente started about a year ago. Since, they have offered vegetarian meals, taught healthy cooking, and held discussions on controversial topics involving conscious consumption. Their aim is to change perspectives.

For these people, the push to eat consciously accompanies opposing foods that produce excessive greenhouse gases, climate injustice, and compromise human rights.

Through specific initiatives, they seek to change attitudes towards eating in a society known for its traditional approach to food. 'Avoiding meat once a day is a start. On this day, we invite everyone we can. No meat, no soya. Sharing the food is the soul of it all.'

Paola Mejía of CABOLQUI believes that the ripening movement in Bolivia mirrors trends from other places in the world, where people are willing to pay higher prices for food that is produced ethically, with a devoid of genetic and chemical impurities. For her organisation and its partners, roots are what matters. Western demand and innovations in methods of production are destroying cultural and biological diversity. That is what Bolivians, through seeking different approaches to food and conscious consumption, are resisting.

Download

Download