Understanding Suma Qamaña from the Outside

'We, the indigenous peoples, only want to Live Well, not better. Living Better is to exploit, plunder, and to rob, but Living Well is to live in brotherhood.'

- Evo Morales

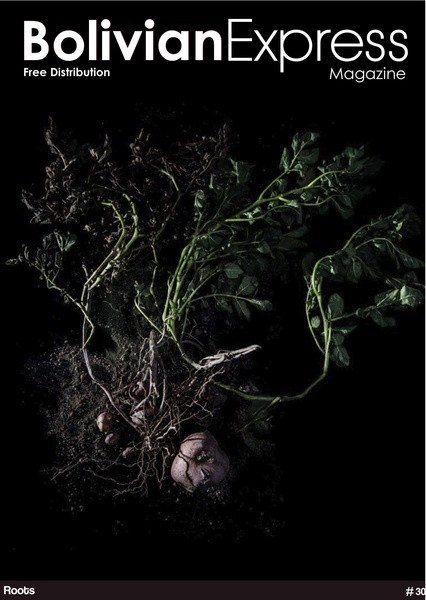

Photo: Andy Baker

In the cold Andean regions of Bolivia—the Tierras del Altiplano—when a man and a woman form a union, it is customary to hold a great feast to formalise the matrimonio . The celebration, filled with music, dance, and drinking, is a way of revering and thanking the gods, and of publicly recognising the bond. After a moment of reflection and marital advice, the community wishes the pair well-being — that they do not only live well within their own world, but that they live well with all other worlds.

This was how I understood Simón Yampara's first explanation on the origin of the Suma Qamaña concept. It was an ideal, he told me, a desired state that not only meant good life, but the accomplishment of holistic well-being.

Sitting across the table and shifting his gaze from his hands onto me, the Aymaran sociologist, who is credited as the primary proponent of this concept, talks with ease as I struggle to get all of his words onto my notebook. As he delves into history, he introduces me to a breadth of Aymara terminology which, for the sake of not interrupting him, I decide not to ask him to repeat. His second explanation was arguably more interesting.

'I was not convinced by the Marxist Theory of class struggle,' he said. 'So, I went back because I wanted to find out what these concepts and what the economy meant in an Andean setting. But then, I found out there is no Aymara word for “economy.” The closest idea they had was actually more all-encompassing, and that was Suma Qamaña.'

I will admit I do not know much, if anything at all, about Bolivian politics and economics. I may have shallow knowledge about some issues, though I know two months in this country is not enough to learn about them in detail. However, having come across one of the more interesting and, perhaps, controversial topics to spring from none other than this country - the issue of 'Vivir Bien' - I decided to take advantage of my stay here to at least acquaint myself with this intriguing ‘new’ idea.

El Proceso de Cambio is the name given to the broad-reaching social and political changes the government credits itself for putting into motion during the presidence of Evo Morales. According to the administration, necessary changes must be made for Bolivia to attain true nationhood; and these, so far, have included the nationalisation of energy resources, dismissal of foreign firms, the banishment of the United States ambassador, and most recently, the expulsion of USAID, the US aid agency.

But what has arguably been the most striking governmental action attributed to this process, was Morales's denouncement of neoliberal economic models and his proposal of an alternative paradigm. In declaring capitalism as the ‘Path towards Death,’ he presented a set of commandments that would supposedly serve as a means to save not just Bolivia, but humanity and the planet. The tenth, and last, of these being a ‘revolutionary’ concept that allegedly takes its roots from the ancient Andean Cosmovision.

This paradigm, supposedly based on respect, reciprocity, and harmony with beings in coexisting worlds, is the Morales Administration's proposed replacement to the selfish and destructive Western models of development. Achieving growth through the revival of the indigenous relationship with Pachamama, or Mother Earth, is the 'Path to Life,' according to Evo Morales. This is El Vivir Bien. This is Suma Qamaña.

Admirable as it may sound, however, there have been several reservations regarding Suma Qamaña's viability as an alternative to capitalism and/or ‘traditional’ socialism, within the country and outside. Though certainly ideal as a theoretic construction, it seems far too vague for realistic application, and its origin and translation leave much to be answered as well.

'Indigenous Bolivians are principally pro-development,' says Pedro Portugal, director of the Bolivian newsletter Pukara. ‘They want to produce, they want to work. But the government romanticised the image of the indigenous peoples and made it inconsistent with reality. The people described in this Suma Qamaña could never be found anywhere because there is no such place. Suma Qamaña cannot even be found in indigenous political history. It just suddenly emerged.'

According to him, the Suma Qamaña presented by the government — the communitarian utopia occupied by ‘good indigenous people’ who consecrate nature and whose dedication is mainly on the preservation of their ancient way of living — is a myth. Real Andean Cosmovision is more linked to progress and that is what the indigenous, like most other people, want for themselves, he says.

'The indígenas are communitarian due to survival, not for its intrinsic virtue. The same people who are communitarian in the campo, when they go to the city and encounter economic and social changes, inevitably become individualistas,' he continues.

The government's basis for this developmental paradigm may not just be weak, but made up altogether. In fact, the vision it advances may not even be all that different from prevailing economic systems. At least, not as it would seem from what the government is actually doing. Judging by the fact that a large portion of Bolivia's national income still comes from the extraction and exportation of non-renewable resources, the internal contradictions are not at all hard to make out.

'Suma Qamaña is what the government uses in discourse, but in reality, the Bolivian economy works under the classic system of capitalism. The government sells raw materials — for example, gas to Argentina and Brazil. It sells to anyone who wants to buy. It takes place under real economic mechanisms. The problem of the government is that it has to get out of its own contradiction with reality. Anything the government does is bound within the limits of the classical world. It has to stop distorting practice and discourse,' declares Portugal.

'Suma Qamaña is a paradigm of life,' according to Simón Yampara. 'But there are different kinds of good living for every type of person. Every horizon needs to be respected.'

Emphasising that the application of this idea as an economic concept would be equivalent to reducing its essence, he adds that the scope of Suma Qamaña goes beyond just this world. As far as it is concerned with material well-being, it also involves an important spiritual dimension. It never covers only one aspect.

So does this ultimately mean the government is not actually adhering to the paradigm it is supposedly reviving? Perhaps. The main problem is that the idea by itself remains too abstract and its lack of specificity makes it inevitable for action to contradict words. It is an arguably valiant cause to strive for this ideal, but as we might have known by now, what good is differs for every person. Who is to say, then, what is involved in Living Well and what Living Better consists in?

Caterina Stahl was abandoned twenty-one years ago in Oruro, Bolivia, as an infant. Adopted by parents from the United States, she has lived there her entire life. She returns to revisit places only known to her through anecdotes and photographs, and in the process re-lives a past made present through fragments.

Life is marked by milestones: learning how to tie your shoes, getting a driver’s licence, getting accepted into college. All these moments, big and small, make up a timeline of who you are. My own personal milestones include one I can’t always share. It’s of being left behind. Being left to the unknown. Being transferred into the arms of strangers who would eventually become my everything—my family.

When I was growing up, the story of my early life sounded like a fairytale to me when my parents told me about it. In July 1992, I was left on the steps of a bank in Oruro, Bolivia, when I was only months old. The police were called around 9:30 am, and I was quickly transferred to a local orphanage. The authorities placed an ad in the newspaper La Patria with my picture, hoping that my parents would come forward and take me back. They never did. I lived in the orphanage until I was about 6 months old.

Oruro: The Journey Home

Sometimes I can picture myself as an infant, swaddled in a blanket in a small basket hidden amidst the chaos of Oruro streets. I am afraid at the noise that surrounds me. I do not like the unfamiliar surroundings, and I struggle for comfort, wailing for the loving hands—or maybe not loving, but familiar hands—that have just left me. But the world keeps going and I, from this moment on, am lost forever, unidentified, and in the worst way, abandoned.

Fast-forward to the present. I find myself yet again consumed by confusion and chaos, but this time I’m at the La Paz bus terminal, and I am no longer an infant, but a 21-year-old woman.

“¡POTOSI! ¡ORURO! ¡SUCRE!”

Oh my, which way do I go? I couldn’t remember what bus was the best to take. I run into a woman who immediately begins writing me a ticket. Zip, zap, zam, I run through a hidden door and trip over a few cholitas

, then board a bus that’s already moving.

I relax. I’m in my element. I’d grown up in constant movement. I travelled down the Death Road to Coroico with my adoptive mom when I was months old. I used to climb out of my crib when I was 2 years old. I’d climb anything to move ever higher and faster. I’ve chased everything from my dreams—boys, hockey pucks, and moving buses in La Paz.

No surprise, then, that instead of staying in my comfort zone, I moved to La Paz in my last free summer before graduating college, before entering the adult world. I always knew I had to come back to Bolivia. It’s where I began, where my roots are.

The bus drops me off on a street corner in Oruro. Panic takes over my body. I’m so alone, and I’m so American. I finally managed to find my hotel room. Sitting on my bed underneath the Jesus figurine nailed to the wall, I can’t shake the outskirts of Oruro from my mind. The poverty in the surrounding towns is appalling. The broken and crumbling buildings look so poor, sad, dusty, and deserted. The city center, though, is much more built up than I’d imagined—there’s even a large digital billboard in one of its streets!

I feel like I’m looking into a goldfish tank. In La Paz, I didn’t mind being a typical tourist, but in Oruro, I expected to be less like a fish out of water. Instead, I find myself looking at everyone from the outside, the same way I feel in the United States sometimes. I am an American—I have American dreams, an American accent, an American passport —but when I catch a glimpse of my face in the mirror I look alien, different from my family and friends. And here, too, in Bolivia, I might look similar to everyone else, but when I open my mouth it’s clear I don’t belong. I feel like I’m caught in a limbo of sorts—love from my family and friends surrounds me back at home, but a desire to know more crushes me. Here I am now, though, looking for answers, looking for the truth to set me free.

Returning to My Roots

I finally find the courage to leave my hotel, and I walk on autopilot to the place where I was abandoned: La Plaza 10 de Febrero.

I’d always pictured this place as cold, all stone and dull grey, but it’s the opposite. Gardens are scattered around the plaza, and gold statues of animals and cherubs decorate the fountain at the center. Kids climb the statues, couples lounge on the benches, and people flow like traffic in all different directions, entering and exiting the plaza.

The bank where I was left—now a Banco Bisa—looks simple. It’s a brown and white building with little traffic on the outside. The emotion I feel isn’t so much from seeing the bank, but knowing that twenty-one years ago my mother or my father walked these streets with me. Maybe they sat on the bench I’m sitting on now, waiting for my new fate to unfold. Maybe they walked away quickly with eyes like two shining stones at the bottom of a deep well, crying for the baby that would never again be theirs.

I sit in the plaza trying to let go of an anger I’d been in denial about throughout my whole life. I never wanted to be mad. I’ve had a better life than my birth parents could ever have imagined. It’s hard to know sometimes which is better: to be in poverty but still a direct growth from my original roots, or to have that second chance, like pollen blown away by the wind to germinate and grow, lay down roots elsewhere so very far away.

I could have been the little girl I see running through a field of trash collecting anything reusable. I could have been that cholita begging for money on the street, whom passersby ignore. A kid with a wad of pink balloons runs across the road. Life goes on.

The Discovery

Photo: Caterina Stahl

It’s the morning of June 30, and I’ve found nothing but dead ends. I get hit on instead of helped out, I can’t find any of the offices that might have information. I am losing faith. I feel like a pinball, bouncing from location to location through the town in a pointless search for clues to my past. People start to recognise me as I pass by them again and again throughout the day. I’m hungry and discouraged; the clues to my past that I picked up in La Paz have led nowhere. The signs are telling me to give up.

After a moment of weakness and self-pity I realize there’s no other option but to continue looking. I remember someone told me that orphanages in Oruro are not referred to as orphanages but ‘hogares de niños.’ With the help of Google I find a newspaper article that will change my life.

It’s an article about the seven orphanages in Oruro, written three years ago. What catches my eye is the name ‘Gota de Leche’—’Drop of Milk’—a specific orphanage for children ages 6 and younger. My parents had told me I was left in an orphanage fitting that description. I find a second article from last year about plans to renovate Gota de Leche. There is hope!

I run to the fancy hotel in town, hoping someone might speak English. ‘Does anyone, anyone around here speak English?’ I beg the hotel staff. They end up sending me to the office of tourism. No one there speaks English either. I’m sent out of the building to another office. That’s where I find my angel, Alejandra Soliz.

At first I’m too overwhelmed to tell her anything. Finally, I produce my adoption paperwork and lay it on the table and begin to tell her my story. Before I know it, I have an address for Gota de Leche, and a possible lead on Marcela, the matron of the orphanage who cared for me. Alejandra tells me that it is common in Oruro for babies to be abandoned in trashcans and on the streets. ‘For religious reasons mostly’, she says. ‘The mother almost always disappears immediately after. Even the police can’t find them.’ Fate can sometimes be kind, and Alejandra is proof of that. Before I know it, she puts me in a cab to the Gota de Leche orphanage. ‘Make sure you come back after and tell me how it goes’, she says as the cab door shuts.

Finally Free

When you dream about something for so long, it becomes a fuzzy picture in your mind to file away with past fantasies. My dad had told me he remembered crossing a set of train tracks on the way to the orphanage located on the outskirts of town, the same tracks that my cab is now crossing, and my dream begins to wash over me again.

The orphanage looks just as my parents had described—a barbed-wire fence surrounds it and an old playground in the courtyard. Matron Marcela is no longer there, but hermana Jhaana is supposed to help me. ‘Estoy buscando a la hermana Jhaana’, I say.

I find her sitting in an office piled high with papers. I know, somehow, that I’m in the right place. I take out my documents again and begin to sob. Hermana Jhaana knows what is happening. She knows I’ve wanted this moment for so long I’ve begun to believe it would never happen. She holds me and laughs with me at the impossibility of it all.

Fate is again in my favor when I discover an American volunteer, Julia, who helps me bridge the language gap. ‘I can’t believe you found this place’, she says to me. ‘No one ever finds this place—it’s almost impossible.’

Julia shows me where I lived during in my time there. There are two rooms for the infants to sleep, and one big room with rows and rows of beds for the older children. The floors are very shiny and the hallways tall, illuminated by big windows. The fenced-in area outside the hogares de niños is dusty and grey; laundry hanging from clothes lines and colorful playground equipment outside make it look less oppressive, almost friendly.

All the babies are resting in a little room sprinkled with toys and sunlight. Julia tells me everyone has a connection with certain children there, just like Marcela had with me. Each baby looks healthy and strong. It’s like looking into a past I can’t remember, but that’s somehow right in front of me, like I’m looking back two decades at myself.

Hermana Marcela and Caterina at 6 months old

My story, I find, is all too common in Oruro. It’s humbling to learn the stories behind each child. Some have been abandoned like I was, or left in hospitals after their births. Some have been taken away from mentally ill or alcoholic parents. There are also horror stories of babies left in trash cans and much worse. If the kids are not claimed by age 6, they are transferred into a foster system until they are 18. I’ve been given so many opportunities by living in the United States, so it makes me happy to hear that the kids who don’t get adopted can find success in life (teachers, doctors, architects) when they leave the system as young adults.

The ‘Why?’

Being a journalist, I’m always looking for other peoples ‘why?’—why they are they way they are, why they’ve followed one or another particular route in their lives. Why they live the way they do. It’s always fascinated me; I’ve always had to know more, always had to know how the book ends before even reading it.

Through unexpected dedication and kindness of current and past employees of the Gota de Leche orphanage I finally found my ‘why?’. I’ve learned that Marcela now lives in La Paz, she remembers me, and I will be reunited with her soon. I’m also told by Señora Ely Blass, who worked at Gota de Leche thirty years ago, that all the babies in 1992 were adopted. They went to France, Argentina, and the United States, and, like me, many have come back to Oruro, searching for their beginnings, their ‘why?’. I find it comforting that I’m not alone in the way my life began. I am happy. I am finally free.

I close my story with these words directed to my birth parents.

For whatever reason you had to say goodbye, I know that you left me with a gift. Your final gift, other than life, was to give me a world full of opportunities that would have been but a distant thought, setting on the horizon of my life, forever darkened by night. And now, because of you, the light of the sun keeps my dreams alive, and as long as I’m living, you are living with me too.

Download

Download