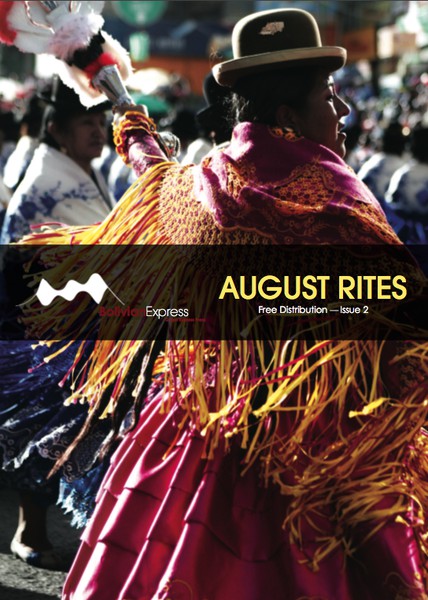

I couldn’t help myself. Bolivia’s festive fever swept me up and carried me off to where I wasn’t supposed to be, to Copacabana’s celebrations. As I was assigned to report on everything that wasn’t August, this festival was left without coverage. So I went undercover to share one last rite of August with you.

Copacabana´s independence day festivities display the Bolivian standard: syncretism. Celebrated in the first week of August it is not just about liberty, it is also a religious festival dedicated to the Virgen de la Candelaria. I arrived on the last day, and like thousands of faithful already had that week, I climbed the steep path up the Cerro Calvio, the 3966m peak that overlooks the town. Numerous stalls occupied both sides of the path, many selling miniature items like model cars or houses for people to offer to the statue of the Virgen at the top. Candles burnt around the many stone crosses that guided your way to the top, and Yatiri shouted prayers, sprayed beer, and let off fire crackers along the sides of the path, adding to a chaos in which I saw a small boy accidentally set alight a large wooden figure of Jesus.

I had come here without aspirations to mysticism, greedy for a chance to partake in this month’s festival analysis, searching for moments to make droll commentary. But, as I reached the summit and the spectacular view of Lake Titicaca spread out beneath me, my senses reeled. Dizzy from the climb, and with the Yatiri’s rough cries resounding through the crowds and encircling my head, the candles took on a misty, reverberating sheen. Even I, a disbelieving observer, found myself prey to a most unsettling and powerful sense of spirituality.

‘Chicken’, noun: as well as referring to the animal, the word can colloquially mean ‘cowardly’, alluding to a certain deficiency in one’s virility. But Evo Morales seems to believe that the link between poultry and ponciness is stronger than that, as he made evident at a climate change conference in April of this year. Watch out, Evo warned chicken-eaters everywhere: thanks to ‘feminine’ hormones in everyone’s favourite fowl, you’re soon to turn gay and bald (‘in the shit’ in more ways than one. Ahem). In catchier terms, chow down on chicken and you’ll soon be eating more than just the feathered variety of cock. The idea that homosexuality, effeminacy and deviancy are linked (according to Evo, gay, bald chicken-eaters ‘experience deviances in being men’) got me wondering about the status of homosexual men in La Paz: in a country that’s progressing in so many fields, how goes it in the world of gay?

At first, gay La Paz cowers from me: it doesn’t just seem to be underground, but locked firmly away in some heavily-guarded closet. Scouring the internet I can’t find anything other than a few out-of-date websites telling me that Catholic Bolivia is a raging homophobe. With some patience, though, I finally find the right places to look. I find LGBT welfare sites, groups of Bolivian Facebook users rallying together in the fight against discrimination, and even more groups looking for casual sex, particularly in Santa Cruz. Browsing Bolivian classifieds sites such as mundoanuncio.bo I find more adverts from guys looking for intimate encounters (one particularly romantic one stands out: ‘semi-semi-transvestite’ – that’s two ‘semis’ – ‘seeks the best sex available for thirty-five bolivianos’), but several from men just looking for more than just your average gang-bang (‘This is a serious advert,’ one man professes, ‘I’m looking for a chubby man over forty to begin a serious relationship’). It’s perhaps telling that sites such as these are so popular in Bolivia – with neither a significant openly-gay population nor a prominent gay scene, where else can Guido meet his soulmate Luis?

Another reason for all this hush-hush might be the prevalence of machismo, at least according to a recent study of masculinidades (published online at cistac.org). One report by social anthropologist Pilar Arispe mentions the frequent use of expressions such as ‘no seas maricón’ (‘don’t be a faggot’) in schools, while another by Claudia Vincenty lists various understandings of maricón, including ‘cowardly’, ‘someone who always complains’, and ‘someone who doesn’t know how to confront their problems.’ Not a world away from the English ‘faggot’, then: to be gay is to be effeminate, which is seen as undesirable.

“Machismo is everywhere, though,” David Aruquipa, a chief member of the transvestite troupe La Familia Galán, reminds me, “not just amongst gay people.” There’s actually a lot of openness in La Paz, David tells me; given the city’s cosmopolitan nature, there’s plenty of room for sexual diversity. Bolivia’s capital also allows for different ways to live as a gay man: there are those that prefer going to gay clubs (of which I can find no trace in the city or online), having their own ‘intimate’ space as David calls it, and there are those who will go to any old place to express their sexuality however seems appropriate. (Depending on how the mood takes you, this may involve dressing up as the opposite sex or, as a few of the more attractive members of the Bolivian Express team have fallen victim to, going to a club like Namas Té and trying to suss out the sexuality of one’s prey of choice by asking them: “So, have you seen any girls you like here?” Each to their own.) “In La Paz,” David finishes, “the gay scene is very political. We discuss sexuality through art, through culture; it’s about promoting diversity, it’s about human rights.”

Ricky Martin: GAY

Talking to the Familia Galán, I start to feel as though things are looking up for the gay population of Bolivia, or at least in the bigger cities of La Paz and Santa Cruz. Not only has Evo since admitted that there are ‘gays in the Palacio’ but in the last few months citizens of La Paz have witnessed a successful Gay Pride March, an LGBT film festival screening pelis from countries such as Bolivia, Peru, Germany and the USA, gay art exhibitions, and the painting of a sexual diversity-themed mural near the Puentes Trillizos (and who can forget what Ricky Martin did for the Spanish-speaking world when he chasséed out of the closet in March?). In any case, I can’t shake the feeling that the link between birds, baldness and buggery just won’t stick. Dunno why.

The Middle Eastern restaurant Café Beirut has a nice Arabic flair, with one wall completely covered with pipes of varying sizes; it also boasts a lot of sitting space and a separate lounge area to smoke, whether it’s cigarettes or shisha you want. The food, both Lebanese and more international, is of a good standard, with falafel, hummus, and even hamburgers, all very tasty and of a mid-range price. One of Café Beirut’s most unique features is that the service is not only friendly but, in contrast with most other Bolivian restaurants I’ve been to, quite fast: with one press of a button, a waiter or waitress will magically appear at your table. All in all, a good restaurant for a nice, relaxing evening!

Location: Av. Montengro, (591-2) 2774496

Download

Download