It’s Saturday morning, and the sun lifts its golden face to welcome a flood of activity bursting down along the Prado. Locals are filling up the streets at a rapid rate, the tourists are out in their forces armed with cameras and copious amounts of sun protection whilst long-limbed women parade up and down the street in outfits worthy of a parental guidance warning. The ignoramuses amongst us may be led to believe that we are bearing witness to the alleged greatest fiesta on earth, the Rio Carnavale. But this is not Brazil, this is Bolivia. The hop, skip and a jump of the dances is more folk than Salsa and more likely to get you bopping along than hot under the collar.

In England, as in Bolivia, bells attached to a man’s leg is a clear sign of a folk dancer. But, unlike in England, folk dancing is cool here. 72 faculties, with over 200 people involved in each, massively outshines folk activity in Britain. Sidmouth Folk Festival, the largest of its kind in the UK boasts a mere 1000 participants, whilst here there are well over 14 000.

As each 30-man-strong-band nears the crowds, we are assaulted by the lead melody from the big brass section. Although the music contains melodic, embellished tunes from the pan pipes and wooden flutes, these are drowned out by the shrieking trumpets and their brothers. The lack of accordian or fiddle clearly highlights the difference between the folk music of Bolivia and the Celtic influenced folk music of Britain.

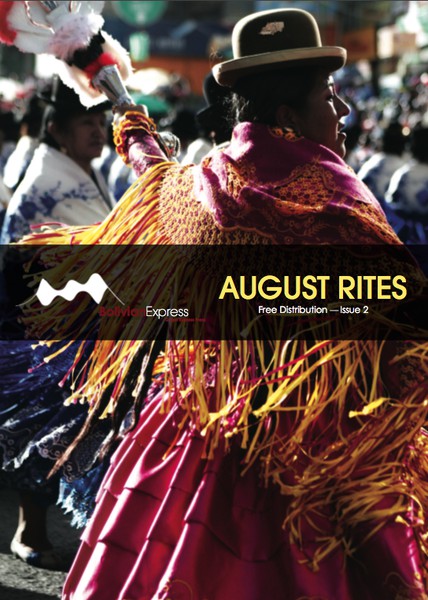

Although the costume designs, like the music, have been around for many years, no group looks the same. Faculties performing the same dances distinguish themselves with their differing takes on the traditional dress. The general ethos: the more glitter and sparkle, the better the costume, especially for the Morenada and the Caporales. The dresses worn by young women, although very very short, hold certain similarities with the current trends within the competitive Irish Dancing community. Some dances, such as the Jalqa, stay very true to traditional dress, with women carrying flowers in baskets and on their backs, while wearing long black dresses with bright, ornately stitched aprons, strikingly similar to traditional Dutch dress. The accompanying men, meanwhile, wear white trousers and shirts with decorated belts, a reminder to us English gringos of Cotswald Morris dancing.

From dance to dance, the type of costumes varies from cholita-esque skirts to sequined loin-clothed hunters, and from incredibly decorated warriors to the cowboy boots and harem trousers of the men in the Chacarera. Each and every costume is breathtaking to look at and collectively the big, bright colours make the procession a visual treat. The Tinku warriors jump from side to side, touching the floor, then the sky, in a dance inspired by battle. Between routines, the dancers gather together in large circles chanting to each other, keeping group morale high. The Chacarera proves to be one of the more complex dances, with the women dancing around the men, swinging their skirts in a style reminiscent of flamenco, while the men clap, tap and stamp their feet while jumping around, with a never ending abundance of energy, similar to the ceilidh dancing of the Celts. Although the Morenada and Caporales are the more sedate of the dances, with the dancers only seeming to swish their hips while moving backwards and forwards, frequent echoes of “BESOS, BESOS” (“kisses, kisses”) everytime the girls walk past demonstrate that these were the most popular dances amongst both the performers and the crowd. (I wonder why.) As the day progresses, the readily available Paceña further enhances the happiness of all involved, though causing the parade to descend into chaos! By evening people have left their seats and are dancing amongst the procession, slowing an already protracted parade to an almost standstill. Although the dancers have lost their coordination and the music is out of tune, the sheer enthusiasm of both the performers and crowd keep the euphoric spirit of the Entrada alive and beating long after the sun decides to turn in for a well-deserved descanso.

Dances:

Morenada:

a vibrant dance from the Bolivian Andes, appropriately performed by the Facultad de Agronomía. Feathers, googly eyes and very short skirts.

Diablada:

a highly energetic dance with an enormous dance troupe from the Facultad de Medicina. Stethoscopes included. A dance of combat that originates from Oruro and climaxes in a duel between St Michael and the Devil. The seven deadly sins and ornately dressed angels with very high hemlines also feature

Caporal:

KNICKERS KNICKERS KNICKERS. Colour co-ordinated underwear are a major feature of this dance. Despite the focus on female lingerie, Caporales has it’s roots in religion- the dance is intended to honour the Virgin of Socavón.

Tinku:

Very physical war dance from Potosí. Male and female dancers are separated whilst Chinese dragon-esque characters thrust between them.

Chacarera:

A partner dance from the Bolivian Highlands that is reminiscent of Flamenco. Lots of dress swishing. One unlucky lady got her skirts stuck to her head which seems to be an occupational hazard of this flamboyant dance style.

Who will sow the land? The Jalqas sow the land. When I decided to join the Jalqas I did not realise the gravity of what I was undertaking. Enticed by merrily leaping couples, it seemed like a fun dance to take part in. Certainly it is a community dance, and the compact sense of unity that drew me in, the vision of 40 people swaying as one block, proved most satisfying and real. But what had seemed so joyous in rehearsals, on the day of performance became something far darker and far more profound.

The preparatory atmosphere up at the top end of the Prado was not unusual. The men arrived in their home clothes, and slouched around with their costumes tucked sheepishly into their bags. The women arrived dressed, and began the community ritual long before dancing. We eyed the Morenadas, and complimented them. We eyed the other Jalqas group, and said, “They have a nice pattern on their aguayo. Our dress is prettier though.” As we waited we helped each other arrange the flowers and pin them to our backs. Before dancing, we left our bags in the ornately adorned car that would drive before us. We pressed up to the door, whilst within our leader, Yana, sat like some aged Queen in a litter, and leant heavily out to receive our offerings.

The struggle began when we tried to secure our place in the procession. We were one of the last to enter, our fraternity having not yet gained the age and status to begin earlier in the day. But we were late. The band was not to be found; we rushed around anxiously, locating first a lone trumpeter, who finally made out his friends, engrossed in the latest Caporales entry. By this time the Miners, who came after us, had already begun to advance. We dashed in front of them and asserted our position in spite of their threateningly advancing truck. They were displeased, but we stood strong, still untangling the chaotic mix of dancers, band-members and dislocated couples, but refusing to budge from our proud place at ante-penúltimos. Last year we had been penúltimos.

By this time, darkness had fallen and the cold was beginning to bite at my sandaled feet. Our slow start did little to relieve the chill; the bands were too close together and my bloque could not coordinate: those at the front of the group were dancing to a different, faster band than those at the back. What had become so slick in rehearsals here broke down into laboured fragments; at first overpowered by the unequal brass bands, we soon found that they had left us behind, and scurried and stumbled along in an attempt to keep up with the rapidly fading music. Our movements were less dance than swaying run, and the road panned out before us like a desolate highway. I despaired.

But in this very wretchedness lay the heart of the dance. Beating unevenly, by the time we passed San Francisco it had gained in constancy and power. Our movements began to come together, steadily and tragically. The women, in our great black dresses, chimed like dark bells. No one was smiling. The men bent low, swinging their pick axes at the tarmac. The leaders of the group marched down along the files, barking, “Agachense! Que bailen, bailen!”, and the women bent low too, still swaying, sowing seeds into the street. We rose, wheeled and spun, subservient to the cry of the leaders and the demands of the ground. The flowers on our backs drooped and sweated, but remained pinned tight. Sometimes despondently, I noticed that hardly anyone was watching us. Men in orange jackets swept the streets, the stands were being dismantled and red Paceña banners fell graciously over our heads. Families walked home, carefully avoiding the leery drunks, and in dark corners, some couples kissed and huddled. No one seemed to care for us, dancing there in the centre under higher orders. But this bleak and tired atmosphere was borne out by the Jalqas. Toiling increasingly painfully down the road, I felt gradually lifted by the grave dignity of it all: a melancholy procession, blared at from behind by the brass, pursued by miners and devils, and tethered along by a weary yet irrefutable instinct to cling to the road.

As we neared the Palco, our leaders’ severity mounted, their voices cracked above our heads like whips, and we gathered ourselves together to prepare our entry to this ultimate, brightly lit arena. We lived these final steps wholly: the bloque strode forward as a unit, the men swung the women round them in a solid formation, us women heaved and chimed our knells, our lips drew into small smiles. We had had our swan song.

Was there anyone left in the Palco to see us? It didn’t really matter, our symphony had not been danced for onlookers. It was a declaration, here at the eve of a long and revelrous day, that we remembered the cold dread of the Altiplano, the labour of the countryside, ploughing forward through the seasons, sowing and harvesting the potato crop. We remembered that triumph was our life, and reward was our death, death that kindly awaited us at the end of a long and agonizing journey.

In the Zona Sopocachi of La Paz, things are peculiarly quiet. The normally chaotic traffic is calm, and pedestrians cross the road with relative ease. Shops are shuttered up, cafes are draped in red, yellow and green, and the rusty smell of a barbeque drifts over a garden wall. The famously hectic city is having a break. It is 6th August, and a national holiday, for, one hundred and eighty-five years ago today, and after a sixteen year war, Simón Bolívar declared Bolivia’s independence.

As I stroll up towards the Prado, kids are having ice-creams, their parents sitting relaxedly in the sun, and a couple walks hand in hand, in matching Bolivian national football shirts. It may be of some surprise, therefore, that of all the people enjoying a day off work, the attractive television reporter and accompanying cameraman coming down the street pick out the only other person who is (nominally) working. They ask me if I’m having fun, where I’ve been, and I respond as best I can, in broken Spanish. It becomes quickly clear that maybe, just maybe, I am not the most authoritative person to articulate the nation’s patriotic sentiment on what is perhaps the most important holiday in the Bolivian calendar. I try to explain that my Spanish isn’t very good, but she presses on. The questions get more complicated, and the conversation stalls further. Eventually, my questioner despairingly implores, “Repeat after me: Viva Bolivia!”

I oblige, but it starts me wondering. Was it really necessary for those words to come out the mouth of an ignorant, illiterate gringo? The predominance of white skin tones in media and advertising was covered in an article last issue, but if the very day of a country’s liberation from colonialist oppressors isn’t a day to actually ask Bolivians their own opinion, then I’m not sure what is. Bolivar is often described as “South America’s George Washington” for his role in bringing democracy and self-determination to the continent, but progress on this front has in fact been painfully slow.

After independence, Bolivia frequently suffered under corrupt governments, usually led by military leaders. Independence certainly did not mark the liberation of the majority of native Bolivians. Universal suffrage was not realised until the MNR revolution of 1952, and, symbolic of their exclusion from the political process, only from this date onwards were indigenous Bolivians allowed to enter the Plaza Murillo. The struggle did not end here, the MNR was soon replaced by a military junta.

Looking at Bolivian history, it is easy to get pessimistic about the development of the state in a post-colonial setting. Even Bolívar himself was far from optimistic. “All we have gained is independence, and we have gained it at the cost of everything else... Those who have toiled for liberty in South America have ploughed in the sea. Our America will fall into the hands of vulgar tyrants.” His words have, unfortunately, proved largely prophetic. Whatever the political problems Evo Morales faces, the significance of his election (if it needed proving) is only highlighted by this context. To his worst critics, he may be a vulgar tyrant, but, to paraphrase Woody Allen, at least he’s for the left, which is good news for native Bolivians. And in time, attractive television reporters may ask them about their country’s independence. For they’re bound to have a damn sight more to say about it than I do.

Download

Download