It’s not often that a president who returns with 64% of the popular vote (nearly 40% more than their nearest rival) faces stern political opposition eight months into their presidency, but then, Evo Morales is not your typical president. Always a controversial figure, the country’s first Aymara President is once again causing a stir among his people, but, worryingly for his government, the traditional lines of division are shifting.

As a champion for an oppressed majority, it hardly needs saying that not all sections of Bolivian society have been fans of Evo. Business leaders and the middle classes have been suspicious (or outright hostile) towards his socialist motivations, and the financial centre of Santa Cruz has been demanding greater autonomy. However, increasingly his regime is subject to protests closer to home, as recent protests over the new customs law attest. On these marches, which are happening two or three times a week, protestations come from both Aymara and Quechua communities, and from regions as diverse as La Paz, Potosi and Morales’ home region of Oruro. During Independence Day celebrations in the traditionally supportive urban expanse of El Alto, a man drukenly heckles the town’s president, proclaiming Morales a “bastardo” before he is dealt with, subtly yet effectively, when his seating is removed.

Why has this change come about? One complaint we hear during a relatively peaceful march is that the enforcement of taxes on cheap imports is tantamount to communism. One wonders what else to expect from a movimiento al socialismo. Of course, not everyone on the march voted for Morales, or at least is ready to admit that they did. But those who do are noticeably embarrassed by their admission. He is branded a “traidor”, and it is ostensibly easy to see why. The enforcement of taxes on cheap imports will raise the cost of living disproportionately for the poor who buy the goods, and also the lower-middle class vendors who sell them. However, there is a definite sense of paradox surrounding the protests, and one gets the sense that, predictably, the people are willing to support socialism only so long as they can benefit from it. As soon it becomes clear that in practice, socialism means higher taxes for all, suddenly it is not so appealing. Viewed as a champion of the lower classes, Morales’ actions can seem treacherous, but as a champion of socialism, his treachery is far less obvious – indeed, to embrace free trade would be far more ideologically inconsistent.

Regardless of such technicalities, if the working classes feel that Morales has abandoned them, opposition will mount and his government could be in trouble. However, it is time to challenge the lazy assumption that the middle classes are necessarily against Morales. His dominant victory in the presidential election reflects a growing support for his leadership in more bourgeois circles. The Bolivian economy fared relatively well during the global financial crisis, growth has been steady, and one section of society that should benefit from enforced trade tariffs are the Bolivian producers and owners of industry. While such tariffs do distort the market, their global presence, from the Common Agricultural Policy in Europe to protectionism of sugar in the USA, reflects the political bonus that governments can gain from interest groups in their electorate.

However, at the moment this political bonus seems dwarfed by the alert consumers of Bolivia, who are most concerned about the costs to their own pockets. What it may boil down to is necessity: whether Morales needs the support of the protesters more than they need the country’s first indigenous president. For the paradox of the crowds suggests that, while they may protest against Evo’s current actions, you wouldn’t bet against them abashedly voting for his party again.

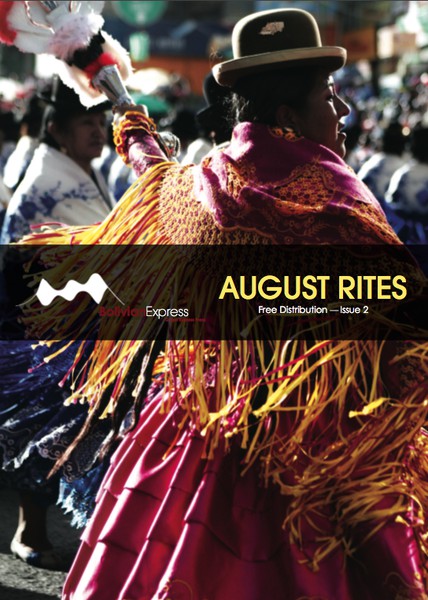

As a European new to La Paz, my first experience of a Bolivian festival was a breathtaking one; as I watched the volume and vibrancy of the Entrada pass, I wondered what could inspire fifteen thousand people in such a collective effort. Moreover, I was astonished to learn that this monumental event was not a one off occasion, but one in a long string of festivals and celebrations threading throughout the Bolivian calendar and bunching up into a prolific August bundle. Whilst my colleagues dashed around surveying the various explosions of colour, light and sound popping off this month, I stepped back for an overview of the Bolivian passion for festivals throughout the year.

Preste

One of the most popular feasts in La Paz, it takes place on a saint’s day and is generally celebrated with a community or family. Starting with a church service, a procession will then leave from the church to one of the families´ houses, with an elder carrying an icon of the saint at the front. It features Folkloric dancing and drinking, need we mention, plus sacrifices to the Pachamama. Once back at the house, a lively party ensues, with each family providing a different commodity, like music, food, or drink. There is also a tradition the parties increase in size each year, so if five cases of beer are drunk one year, six must be provided for the next!

Alasitas

24th January

6 Day festival dedicated to Ekeko, the god of plenty.

Father Christmas, but without the beard, clothes or reindeer. (The likeness is astounding, trust us). Don’t expect your presents wrapped, they come a-dangling off him like little round baubles. If it wasn’t for his pot belly and twirly moustache, you might mistake him for the said father’s tree.

Fiesta de la Virgen de Candelaria

2nd February

Copacabana. The Bolivian patron saint, she’s so special she gets two birthdays, one in February and another in August. (see p23)

Carnaval

February/March

celebrated across the country in the week before lent. The most famous is in Oruro where around 38,000 dancers and musicians participate. The streets fill with furry bears, horny girls (referring obviously to their devil costumes). Careful you don’t get chucked in the fountain, because it’s a tradition for everyone to get soaked.

Semana Santa

Easter

Every year Jesus returns to battle the legions of bunnies advancing towards Semana Santa. In La Paz, he always wins. In the UK he’s less fortunate.

Fiesta de Jesus del Gran Poder

May/Early June

Part III of the Jesus trilogy, it’s a bit like having a posthumous birthday party, which also happens to be La Paz’s hugest Preste. It has always been controlled by the indigenous communities of La Paz, with their different cultures and religions represented in the dances and costumes of the procession, which traditionally goes through the richer, whiter areas of La Paz.

Independence Day

6th August

Fiesta de Virgen de Urkupina

15th August

Spring Equinox

21st September

celebrated at Tiahuanaco, near La Paz. Get up ridiculously early to freeze yourself to death watching the sunrise over some sacred ruins. It’s definitely worth it.

All Saints Day / All Souls Day

2nd November

Persistent with the living, Bolivians can’t stop themselves offering drinks to the dead too. Today’s party is shared with you on p12.

Navidad/Christmas

25th December

You know it already

The church blessing, the Cinderella gown, the bouquet, the tiered cream cake, the first dance…all little girls dream of this day. The average schoolgirl has to make do with playing Polly Pocket weddings until her big day twenty years later; however, girls from Latino communities receive more instant gratification in the form of their quinceañera at age fifteen.

Strictly speaking, this isn’t a wedding: there’s no groom, no honeymoon and certainly no alcohol involved in the proceedings. This is a rite of passage that grants a young girl a “princess for a day” pass, ensuring that she, like a bride, is the focus of her family and community’s adoration. She has achieved the ultimate female accolade: womanhood.

A multitude of cultures and communities celebrate a teenager’s coming of age in a similarly ceremonious manner, the most widely known being the Jewish Bar Mitzvah to signify a boy’s entry into manhood at thirteen. Female rites of passage have often centred on long, regimented practices and prayer once a girl receives her first period, such as the ‘Navajo Kinaalda’, or strict, social introductions into polite society, as demonstrated by the waning French Débutante ritual. Although similarly rooted in tradition, the modern quinceañera blows these rigid rites out of the water.

A perusal of quinceañera boutiques in La Paz proves that it is the Quinceañera herself who is firmly in charge of proceedings. Whilst in the past the quinceañera was a more family-orientated occasion, modern day festivities seem to be modelled on the American Prom and Super Sweet 16 culture, a fairytale indulgence of teenage fantasies encapsulated by Mattel’s new “Quinceañera Barbie” and Disneyland’s quinceañera packages and competitions. This Never Neverland element has certainly permeated La Paz, with fairies perching atop garish pink cakes and Disney princesses adorning the quinceañera velas. For the more fashion-conscious, trend-obsessed fifteen year old, Emo-style gowns have been rushed in from Argentina, ensuring that a Quinceañera needn’t abandon her usual urban outfit of biker boots and black capes. In brief, every shopkeeper that I interviewed emphasised that it is the Quinceañera who personalises the party; the parents merely pick up the bill.

Nevertheless, despite this apparent wave of diva-esque daughters and opulent, superficial banquets, it is perhaps encouraging that young women are encouraged to take responsibility for their own event, as it can only further their sense of independence and self-esteem, essential traits for the modern woman. A 21st century quinceañera does not aim to launch girls into a life of domesticity or marriage, as was the original purpose of the celebration; instead it reinforces a teenage girl’s confidence, inspiring her to chase her own dreams instead of simply living up to family or social expectations.

Over the course of this month, I have definitely watched too many home videos of quinceañera celebrations on YouTube. Some are highly impressive and entertaining in their display of pomp and ostentation; however, it soon emerges that even the most MTV-style fiesta has not lost the gravity or meaning of a coming-of-age rite. It is not the expansive guest-lists or generous gifts that bring a tear to the Quinceañera’s eye; it is the pride of her parents and her first dance as a woman with her father.

Download

Download