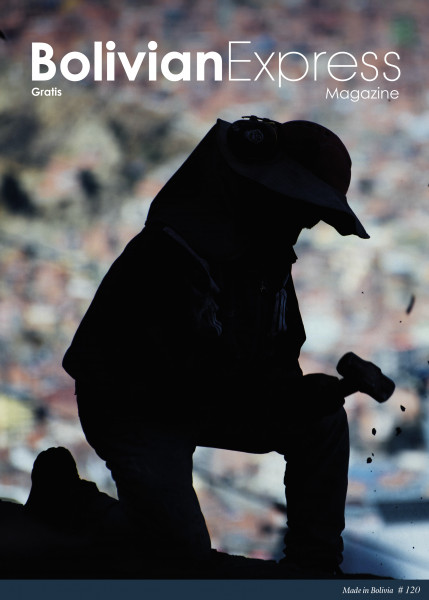

Our cover: Iván Rodríguez

ENGLISH VERSION

Claiming the right to call something your own.

I asked Bolivian cook and salteña enthusiast Virginia Gutierrez if salteñas were sold in other countries. ‘I think they have them in Argentina,’ she said. ‘I'm not sure, though, you'd have to check.’ But a Plaza España salteña-seller was more adamant. ‘Only in Bolivia,’ she told me. Yet, the creation story is as follows:

Juana Manuela Gorriti – a salteña of the non-edible variety – and her family relocated from Argentina to Bolivia in 1831, escaping the Rosas dictatorship. Well-known for her intellect, writing and grief-strewn life, Gorriti was also the inventor of the salteña, and thus named the delightful creation after her home province.

‘It's all in the name,’ goes the well-known phrase. Yet, in this case, all is not in the name. First created and sold in Tarija, salteñas belong more to Bolivia than to the Argentine province in which their creator was born and died.

A person born in one place and then raised in another is often asked where they feel they belong: the country from which they originated, or the one which has grown to be their home? So, this time, I'll provide the definitive, unbiased answer: salteñas are Bolivian, through and through.

If name does not define identity or origin, what does? An official declaration, an agreed split-patrimony, a battlefield victory – the methods used are abound. But do they work? Let’s look at a few other examples of contested, multi-national treasures.

‘The Morenada is linked in no way to the Peruvians,’ claims Milton Eyzaguirre from The Museum of Ethnology and Folklore in La Paz. ‘In Peru,’ he explains, ‘they say the dance is part of a common culture that belongs to all Aymara people.’ But Milton contends the dance, which originated in the Bolivian municipalities of Guaqui, Achacachi and Taraco, has since been adopted by those living further afield on the altiplano. But how did the Morenada leave the confines of these remote communities? According to Milton, ‘Part of Aymara logic is to expand beyond Bolivia, to undertake a cultural conquest.’ Sharing is caring, is it not? Not when others try to claim shared items as their own.

Sometimes, sharing with Peru can be permitted, as is the case of the great Lake Titicaca. The independence of Peru in 1821 and Bolivia in 1825 gave way to the division of the lake, giving Titicaca a dual-nationality. It is almost perfectly divided between the two countries in a compromise that seems to compromise nobody in particular.

Another water-based, less peaceful, but certainly Pacific example, comes in the Bolivian-Chilean dispute over the sea. When Chile conquered Bolivia in the War of the Pacific, it took the country’s access to the sea. All is fair in love and war, right? Wrong. Bolivians to this day are fighting to claim back what they believe is rightfully theirs.

Just as salteñas are unable to declare where their allegiance lies, so too are dances, lakes and bits of land. Whether it is claimed, shared or won, possession remains forever disputed as countries continue to fight over what they desperately want to call their own.

----------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Reclamar el derecho a llamar tuyo a algo

Le pregunté a la cocinera boliviana y entusiasta Virginia Gutiérrez si las salteñas se vendían en otros países. "Creo que los tienen en Argentina", dijo. "Sin embargo, no estoy segura, tendrías que comprobarlo". Pero un vendedor de salteñas de Plaza España fue más inflexible. "Solo en Bolivia", me dijo. Sin embargo, la historia de la creación es la siguiente:

Juana Manuela Gorriti, una irunda de Salta , y su familia se trasladaron de Argentina a Bolivia en 1831, escapando de la dictadura de Rosas. Conocida por su intelecto, escritura y vida llena de dolor, Gorriti también fue la inventora de la salteña, por lo que llamó a esta deliciosa creación en memoria de su provincia natal.

"Está todo en el nombre", dice la conocida frase. Sin embargo, en este caso, no todo está en el nombre. Creadas y vendidas por primera vez en Tarija, las salteñas pertenecen más a Bolivia que a la provincia argentina en la que nació y murió su creadora.

A una persona nacida en un lugar y luego criada en otro, a menudo se le pregunta a dónde siente que pertenece: ¿El país en que se originó o el que se ha convertido en su hogar? Desafortunadamente, los que consumen no pueden responder a preguntas tan complicadas.

Si el nombre no define la identidad ni el origen, ¿qué lo hace? Una declaración oficial, un patrimonio dividido, pero acordado, una victoria en el campo de batalla: abundan los métodos utilizados. Pero, ¿funcionan? Veamos algunos otros ejemplos de tesoros multinacionales en disputa.

“La Morenada no tiene ningún vínculo con los peruanos”, afirma Milton Eyzaguirre del Museo de Etnología y Folklore de La Paz. 'En Perú', explica, 'dicen que la danza es parte de una cultura común que pertenece a todo el pueblo aymara'. Pero Milton sostiene que la danza, que se originó en los municipios bolivianos de Guaqui, Achacachi y Taraco, ha sido adoptada, desde entonces, por aquellos que viven más lejos en el altiplano. Sin embargo, ¿cómo salió la Morenada de los confines de estas comunidades remotas? Según Milton, "parte de la lógica aymara es expandirse más allá de Bolivia, para emprender una conquista cultural". Compartir es cuidar, ¿no es así? No cuando otros intentan reclamar elementos compartidos como propios.

En ocasiones, se puede permitir el compartir con Perú, como es el caso del gran lago Titicaca. La independencia de Perú en 1821 y Bolivia en 1825 dio paso a la división del lago, dando al Titicaca una doble nacionalidad. Otro ejemplo basado en el agua, menos pacífico, se presenta en la disputa boliviano-chilena por el mar. Cuando Chile conquistó tierra de Bolivia en la Guerra del Pacífico, le quitó el acceso al mar. Todo es válido en la guerra y el amor, ¿verdad? Incorrecto. Los bolivianos hasta el día de hoy luchan por reclamar lo que creen que les pertenece por derecho.

Así como las salteñas son incapaces de declarar dónde radica su lealtad, también lo son los bailes, lagos y pedazos de tierra. Ya sea que se reclame, se comparta o se gane, la posesión permanece en disputa para siempre, mientras los países continúan peleando por lo que desesperadamente quieren llamar suyo.

Photo: William Wroblewski

ENGLISH VERSION

This is the story of a girl—let’s call her Lizeth and let’s imagine she’s 10. Lizeth grows up in a small town at the edge of the Bolivian altiplano, and she goes to public school. Every week starts the same way, with the raising of the Bolivian flag and the singing of the national anthem. Lizeth’s favourite classes are Science, Aymara, and Physical Education However, school days don’t last very long: only four to five hours. To fill her free time, she learns how to play rugby from a gringo who recently arrived to teach this unheard-of sport. (She and her friends greatly enjoyed playing against a boys’ team from La Paz and beating them with ease). The other day, her professor of Valores mentioned that an organisation involved in something called ‘integral education’ will come to the town and teach its spiritual programme in the afternoons.

This imaginary but very possible town is closer to reality than you might expect, with Lizeth’s story demonstrating very real changes to Bolivian schools.

Education throughout Bolivia is indeed developing, and has made major, if slow, strides since Law 1565 of 1994, introducing the idea of ‘intercultural bilingual education’ to the country. This has since been consolidated by Law 070 Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) in 2010 which is based around four main areas: decolonisation, plurilingualism, intra and interculturalism, and productive and communitarian education.

Inspired by the latest law and the defining concept of Vivir Bien (Suma Qamaña), the municipality of La Paz has started a programme of emotional intelligence to teach kids how to understand and manage their emotions. In order to advance a ‘secular, pluralist, and spiritual’ education, classes focusing exclusively on Catholicism have expanded their content to values, spirituality, and religions. The new law aims to redefine education to shape a new generation and a new decolonised identity, reinforcing what it means to be Bolivian.

Bolivia does not lack spaces where people share and transmit their knowledge in unexpected ways, from a climbing school in the mining town of Llallagua to talks on the presence of LGBT+ literature in Bolivia; learning is not limited to the classroom.

The long-term effects of ASEP on Bolivian identity and future generations are yet to be seen. Unfortunately, it appears that Bolivia is still divided. There is a very clear disparity between rural and urban areas, rich and poor, boys and girls. Implementation of the law is slow at best. However, this glimpse of the state of education in Bolivia does shine a light on positive developments. ASEP promotes a vision of inclusivity, plurality, and interculturality, combined with an integral idea of education that can only bode well for the future of Bolivian students—young, old and self-taught.

-------------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Esta es la historia de una niña, llamémosla Lizeth e imaginemos que tiene 10 años. Lizeth crece en un pequeño pueblo al borde del altiplano boliviano y asiste a la escuela pública. Cada semana comienza de la misma manera, con el izamiento de la bandera boliviana y el canto del himno nacional. Las clases favoritas de Lizeth son Ciencias Naturales, Aymara y Educación Física. Sin embargo, las jornadas escolares no duran mucho: solo de cuatro a cinco horas. Para llenar su tiempo libre, aprende a jugar al rugby de la mano de un gringo que llegó recientemente para enseñar este deporte. (Ella y sus amigos disfrutaron mucho jugando contra un equipo masculino de La Paz y venciéndolos (con facilidad). El otro día, su profesora de Valores mencionó que una organización involucrada en algo que se llama ""educación integral"" vendrá al pueblo y enseñará su programa espiritual por las tardes.

Esta ciudad imaginaria, pero muy posible, está más cerca de la realidad de lo que cabría esperar, y la historia de Lizeth demuestra cambios muy reales en las escuelas bolivianas.

De hecho, la educación en Bolivia se está desarrollando y ha logrado avances importantes, aunque lentos, desde la Ley Nro. 1565 del año 1994, la cual introdujo la idea de ""educación bilingüe intercultural"" en el país. Esto se ha consolidado mediante la Ley Nro. 070 Avelino Siñani-Elizardo Pérez (ASEP) de 2010 que se articula en torno a cuatro ejes principales: descolonización, plurilingüismo, intra e interculturalidad y educación productiva y comunitaria.

Inspirado por la última ley y el concepto definitorio de Vivir Bien (Suma Qamaña), el municipio de La Paz ha puesto en marcha un programa de inteligencia emocional para enseñar a los niños a comprender y gestionar sus emociones. Con el fin de promover una educación ""secular, pluralista y espiritual"", las clases que se centraban, exclusivamente en el catolicismo, han ampliado su contenido a valores, espiritualidad y religiones diversas. La nueva ley apunta a redefinir la educación para dar forma a una nueva generación y una nueva identidad descolonizada, reforzando lo que significa ser boliviano.

Bolivia no carece de espacios donde las personas compartan y transmitan sus conocimientos de formas poco ortodoxas, desde una escuela de escalada en el pueblo minero de Llallagua hasta charlas sobre la presencia de la literatura LGBT + en Bolivia; el aprendizaje no se limita al aula.

Los efectos a largo plazo de la ASEP sobre la identidad boliviana y las generaciones futuras aún están por verse. Desafortunadamente, parece que Bolivia todavía está dividida. Existe una disparidad muy clara entre las zonas rurales y urbanas, ricos y pobres, niños y niñas. La implementación de la ley es muy lenta. Sin embargo, este vistazo al estado de la educación en Bolivia arroja luz sobre desarrollos positivos. ASEP promueve una visión de inclusión, pluralidad e interculturalidad, combinada con una idea integral de la educación que solo puede ser un buen augurio para el futuro de los estudiantes bolivianos: jóvenes, mayores y autodidactas.

Photo: Ana Diaz

ENGLISH VERSION

Inside the fertile mind of the Bolivian musician, inventor, author and investigator

Once described as ‘the best in the universe’ when it comes to Bolivia’s national-heritage instrument, Ernesto Cavour can be found playing his beloved charango and other musical creations at the Teatro del Charango in La Paz every Saturday night. I catch up with Cavour to discuss his colourful life, in which he’s succeeded in making his creative visions a beautiful musical reality.

Completely self-taught as a musician, Cavour cites ‘a strong and profound love and passion’ as one of his biggest motivations since he first picked up a charango as a boy in 1950s La Paz. His mother, who raised Cavour alone, didn’t want him to be a musician, ‘but I resisted and made promises,’ says Cavour.

This wasn’t his only professional obstacle, however. ‘I was completely timid as a young person,’ explains Cavour. ‘I was scared to get up to the microphone and play… I found it impossible to play in public, and when I did manage to, I’d start to stutter. My voice, my fingers... nothing responded, to the point that I would play almost paralysed.’

But with a successful career as a soloist as well as part of renowned groups such as Los Jairas and El Trío Dominguez, Favre, Cavour, how did he overcome this?

‘One day, a man who came to my house with my neighbour told me, “You play instruments well, why don’t you join the theatre?” And I said, “No, I’m too scared.” And he told me that I needed to socialise with music and art, that I couldn’t just play on my own. And that’s how I ended up joining the national ballet,’ says Cavour.

In this way, the future charango maestro was able to travel all over Bolivia performing for miners and workers, while at the same time experiencing the country’s timeless magic and beauty. ‘The time hadn’t passed, it had stayed in the same moment,’ Cavour reminisces, as he takes me back to the 1960s. ‘Bolivia was paradise in those days.’

‘There wasn’t anyone there to bother me or tell me “You can’t do that!” and there were already a lot of guitar necks. So I made the most of it and that’s how the guitarra muyu-muyu first came about.’

—Ernesto Cavour

It was also during these travels that he started collecting musical instruments of all kinds, a habit that would later influence his work as a museum curator, an investigator and an inventor of musical instruments. ‘I started to collect instruments because they were very cheap, around 15 bolivianos each,’ says Cavour, who appreciated the beauty and the natural, varied sounds of these instruments which were made in the countryside. ‘I saw vihuelas, guitars, charangos, and so many other instruments with different names,’ he continues. ‘There were flutes of all sizes, of every colour, and every material. There were incredible things that just aren’t around anymore.’

In 1962, Cavour founded the first incarnation of the Museo de Instrumentos Musicales de Bolivia in his house. The museum now resides in a beautiful and spacious colonial house on Calle Jaén in La Paz, where it is home to more than 2,500 musical instruments, including pre-Hispanic pieces. The building also houses the Teatro del Charango, an art gallery, a library, and a workshop, where music lessons are also offered.

During a brief tour of Europe in the late 1960s and early 1970s with Los Jairas and Alfredo Dominguez – pioneers of the criollo style – Cavour had the opportunity to develop his skills as an inventor of musical instruments. Inspired by what he observed in the workshops of the master luthier Isaac Rivas, Cavour was further encouraged to invent when he started writing his first music-theory books. ‘I started, for example, writing methods that would allow people to play the charango more easily… because there were no methods available then,’ he says. His first book, El ABC del Charango, was published in 1962, and ‘it was with these books that I started to create.’

In a large abandoned factory in Switzerland, Cavour experimented with instrument design. ‘There were machines there, at my disposition,’ explains Cavour. ‘There wasn’t anyone there to bother me or tell me, “You can’t do that!”, and there were already a lot of guitar necks. So I made the most of it and that’s how the guitarra muyu-muyu first came about. I then finished it when I returned to Bolivia.’ One of Cavour’s most successful musical inventions, the guitarra muyu-muyu has been popularised by the technical skill of colleague Franz Valverde who, along with esteemed quenista Rolando Encinas, accompanies Cavour each Saturday night at the Teatro del Charango concerts.

However, it is the two-row chromatic zampoña that Cavour is most proud of creating. ‘I searched around and figured out how to get all the tones in two rows,’ says Cavour. ‘Of course, it made things very simple. I played it [he hums the flute intro melody from his 1975 carnavalito classic ‘Leño Verde’] at Carnaval and it became famous… It was the departure for the zampoña to be used to make all kinds of rhythms.’

When I ask Cavour about the essence of his music, he is quick to point out that he doesn’t like to sing about women much, as there are so many degrading songs ‘about how [other artists] want to kiss them, their necks… bending them over… it insults women. What moves me more are customs, the earth and its foods,’ says Cavour, who laments that traditional Bolivian music has ‘stagnated’ in general, despite enduring in certain rural areas and with some contemporary musicians. ‘The way the world is advancing… [people] don’t want a huaynito,’ he says, referring to globalisation, consumerism and modern communication’s influence on popular tastes.

Despite this, Cavour has continually produced a lush banquet from the fruits of his passionate lifelong labours. I ask him what he hopes will happen with all this work in the future. ‘The museum still isn’t finished yet. I hope that in a year the museum is done. I have a few very important rooms in mind. It will enlighten the world about things that have happened, things that have been lost. Many tourists come here [to learn],’ says Cavour.

‘What moves me are customs, the earth and its foods.’

—Ernesto Cavour

One room Cavour has in mind will be dedicated to the natural origins of musical instruments. ‘Some things were created to be played as musical instruments,’ marvels Cavour, referring to any number of the naturally-formed instruments displayed in the museum. ‘I’m also working on a book [on musical instruments from around the globe] that will be important at world level. That’s what’s taking up my time.’

------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

Dentro de la mente fértil del músico, inventor, autor e investigador boliviano

Una vez descrito como ""el mejor del universo"" en lo que respecta al instrumento de herencia nacional de Bolivia, se puede encontrar a Ernesto Cavour tocando su amado charango y otras creaciones musicales en el Teatro del Charango de La Paz, todos los sábados por la noche. Me pongo al día con Cavour para hablar sobre su colorida vida, en la que ha logrado hacer de sus visiones creativas una hermosa realidad musical.

Completamente autodidacta como músico, Cavour cita ""un amor y una pasión fuertes y profundas"" como una de sus mayores motivaciones desde que aprendió por primera vez a tocar un charango cuando era niño en la década de 1950, en La Paz. Su madre, que crió sola a Cavour, no quería que él fuera músico, ""pero me resistí e hice promesas a mi mismo"", dice Cavour.

Sin embargo, este no fue su único obstáculo profesional. ""Yo era completamente tímido cuando era joven"", explica Cavour. “Tenía miedo de acercarme al micrófono y tocar ... Me resultaba imposible tocar en público y, cuando lo conseguía, empezaba a tartamudear. Mi voz, mis dedos ... nada respondía, hasta el punto de que tocaba casi paralizado "".

Pero, con una exitosa carrera como solista además de formar parte de reconocidas agrupaciones como Los Jairas y El Trío Dominguez, Favre, Cavour, ¿Cómo lo superó?

""Un día, un hombre que vino a mi casa con mi vecino me dijo:"" Tocas bien los instrumentos, ¿por qué no te unes al teatro? "" Y dije: ""No, estoy demasiado asustado"". Fue así como me dijo que necesitaba socializar con la música y el arte, que no podía tocar solo. Y así fue como terminé uniéndome al ballet nacional ”, dice Cavour.

De esta manera, el futuro maestro del charango pudo viajar por toda Bolivia actuando para mineros y trabajadores, mientras al mismo tiempo experimentaba la magia y belleza atemporal del país. ""El tiempo no había pasado, se había quedado en el mismo momento"", recuerda Cavour, mientras nos lleva de regreso a la década de 1960. ""Bolivia era el paraíso en esos días"".

""No había nadie allí que me molestara o me dijera"" ¡No puedes hacer eso! "", además en el lugar había muchos mástiles de guitarra. Es así que lo aproveché al máximo, lo que llevo al surgimiento de la guitarra muyu-muyu "".

—Ernesto Cavour

También fue durante estos viajes cuando empezó a coleccionar instrumentos musicales de todo tipo, hábito que más tarde influiría en su labor como comisario de museos, investigador e inventor de instrumentos musicales. “Empecé a coleccionar instrumentos porque eran muy baratos, alrededor de 15 bolivianos cada uno”, dice Cavour, quien valoró la belleza y los sonidos naturales y variados de estos instrumentos hechos en el campo. “Pude ver vihuelas, guitarras, charangos y tantos otros instrumentos con diferentes nombres”, continúa. “Había flautas de todos los tamaños, de todos los colores y de todos los materiales. Había cosas increíbles que simplemente ya no existen "".

En 1962, Cavour fundó la primera encarnación del Museo de Instrumentos Musicales de Bolivia en su casa. El museo ahora reside en una hermosa y espaciosa casa colonial en la Calle Jaén en La Paz, donde alberga más de 2.500 instrumentos musicales, incluidas piezas prehispánicas. El establecimiento también alberga el Teatro del Charango, una galería de arte, una biblioteca y un taller, donde también se ofrecen lecciones de música.

Durante una breve gira por Europa a finales de los sesenta y principios de los setenta con Los Jairas y Alfredo Domínguez, pioneros del estilo criollo, Cavour tuvo la oportunidad de desarrollar sus habilidades como inventor de instrumentos musicales. Inspirado por lo que observó en los talleres del maestro luthier Isaac Rivas, Cavour se animó aún más a inventar cuando comenzó a escribir sus primeros libros de teoría musical. ""Empecé, por ejemplo, a escribir métodos que permitieran a la gente tocar el charango de una manera más fácil ... ya que en ese entonces no había métodos muy amigables"", dice. Su primer libro, El ABC del Charango, se publicó en 1962 y ""fue con este que empecé a crear"".

En una gran fábrica abandonada en Suiza, Cavour experimentó con el diseño de instrumentos. ""Había máquinas allí, a mi disposición"", explica Cavour. ""No había nadie que me molestara o me dijera:"" ¡No puedes hacer eso! "", además en el lugar había muchos mástiles de guitarra. Es así que lo aproveché al máximo, lo que llevó al surgimiento de la guitarra muyu-muyu. Luego lo terminé cuando regresé a Bolivia. '' Uno de los inventos musicales más exitosos de Cavour, la guitarra muyu-muyu ha sido popularizado por la habilidad técnica de su colega Franz Valverde quien, junto con el estimado quenista Rolando Encinas, acompaña a Cavour cada sábado por la noche en los conciertos del Teatro del Charango.

Sin embargo, es la zampoña cromática de dos filas de la que Cavour está más orgulloso de crear. ""Busqué y descubrí cómo obtener todos los tonos en dos filas"", dice Cavour. “Por supuesto, hizo las cosas muy simples. La toqué [él tararea la melodía de flauta de su clásico carnavalito de 1975 ""Leño Verde""] en el Carnaval y se hizo famosa ... Fue la salida de la zampoña lo que me permitió hacer todo tipo de ritmos "".

Cuando le preguntamos a Cavour sobre la esencia de su música, se apresura a señalar que no le gusta mucho cantar sobre mujeres, ya que hay tantas canciones degradantes sobre cómo [otros artistas] quieren besarlas, sus cuellos. ... inclinándose ... que resulta insultante para las mujeres. Lo que más me mueve son las costumbres, la tierra y sus alimentos ”, dice Cavour, quien lamenta que la música tradicional boliviana se haya “estancado” en general, a pesar de perdurar en determinadas zonas rurales y con algunos músicos contemporáneos. ""La forma en que avanza el mundo ... [la gente] no quiere un huaynito"", dice, refiriéndose a la globalización, el consumismo y la influencia de la comunicación moderna en los gustos populares.

A pesar de esto, Cavour ha producido continuamente un exuberante banquete con los frutos de su apasionado trabajo de toda la vida. Le preguntamos qué espera que suceda con todo este trabajo en el futuro. “El museo aún no está terminado. Espero que en un año el museo esté terminado. Tengo algunas habitaciones muy importantes en mente. Iluminará al mundo sobre las cosas que han sucedido, las cosas que se han perdido. Muchos turistas vienen aquí [para aprender] ”, dice Cavour.

""Lo que me mueve son las costumbres, la tierra y sus alimentos"".

—Ernesto Cavour

Una de las salas que Cavour tiene en mente estará dedicada a los orígenes naturales de los instrumentos musicales. ""Algunas cosas fueron creadas para ser tocadas como instrumentos musicales"", se maravilla Cavour, refiriéndose a cualquier número de instrumentos de forma natural que se exhiben en el museo. “También estoy trabajando en un libro [sobre instrumentos musicales de todo el mundo] que será importante a nivel mundial. Eso es lo que me está quitando el tiempo "".

Photo: Valeria Wilde

ENGLISH VERSION

The sitting room, with family portraits,glass cabinet of antique dishes and old round table with crocheted tablecloth, felt demure and quiet at first. Suddenly wakes up with the firm strumming of the charango accompanied by lively lyrics.Dressed in a tight white shirt, large belt buckle and dark jeans, his jet-blackhair falling on his shoulders, Saxoman Closes his eyes and delves deeper into the song. He sings of his grandmother,recently passed away. The lyrics ‘I love my mamá so much’ are uncomplicated but genuine. This Latino cowboy is the talented and well-loved Bolivianartist Americo Estevez Roman, better known as Saxoman.Born in La Paz in 1971, Americo is from a family of musicians. His uncle wrote the famous song ‘Collita’ about his wife in the 1950s. Americo started playing drums in a band, Los Casanovas, with his uncles. Experimenting with different instruments, he eventually played the saxophone on the street to make little money to support his family. Hewas spotted and featured by the TV program Gigavision.

The director of the show jokingly called him Saxoman, and the name stuck.Saxoman stops singing and launches into an explanation about how he learnt to play the charango. He wanted to create a Youtube video to welcome Pope Francis to Bolivia.‘But who was going to play the charango for me?’ he asked himself. ‘I don’t know how to play the charango! I’ve never played it in my life!’Saxoman couldn’t find any volunteers, but a friend offered to loan him a charango – for only an hour. ‘“One hour?!” Isaid, “Okay that’s fine.”’ He learnt how to play the instrument in 20 intense minutes.Saxoman’s pope video embodies his determination. Experimental,humourous and enticing, it brings a smile to whoever watches it. One minute Saxoman is playing the charango with Bolivian President Morales’s face in the corner of the screen, the next he is flying through the universe.Saxoman describes this style as slow rock, highlighting his charango playing and his son Gabriel on the drums. He says he made lots of friends through the video. Impressively, it was all shot on an old phone.Through his videos, Saxoman offers an insight into his fantastical world of Bolivia. He is no doubt a proud paceño, as seen by his video entitled ‘La Paz Ciudad Turística’, song with the backdrop of the city at night.

Thousands of lights twinkling in the background give a sense of the expansiveness and vibrancy of the city. Saxoman sings of the majesticIllimani, the iconic mountain that towers over the city.Saxoman and his sons, who form a new iteration of Los Casanovas, simply play together on a balcony. The song begins with drums accompanying an Andean flute, turning into slow rock that also ties in different Bolivian musical styles. Eventually, Saxoman hitches his guitar over his shoulder for an impressive solo. Saxoman’s passion for music is unparalleled. He states, ‘I Fall in love everyday,’ and it is this love that inspires him to write his songs.Saxoman is 45 years old, ‘with the soul of a child,’ he adds.

Every child’s fantasy is to be a superhero, and so Saxoman and his band portray themselves as fictitious characters who carry and play their instruments as deadly weapons to battle the bad guys. Saxoman doesn’t make much money from his music; his only income is from busking. Despite This increasing fame, he wants to stay true to himself and his roots. He’s been featured on Bolivian TV, including LaRevista, and in the newspaper La Razón. Despite this, his main goal is to entertain kids and adults alike, whilst simultaneously making his wildest dreams become a reality. Nomatter how great his future fame, Saxoman says he’ll continue to play music for the people on the streets in the BarrioChino, Miraflores and Zona Sur districts of La Paz.Not only is Saxoman a people’s man, but he is a man of theBolivian people. Vibrant, exciting and determined, he perfectly represents La Paz and its inhabitants. Through his music, Saxoman shares his paceño spirit with the rest of the world. He entertains with all that he enjoys and is fascinated by, be it superheroes, magic and even Smurfs.His music invites you to view life as he does, in a unique and exciting way.

----------------------------------------

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

La sala de estar, con retratos familiares, vitrina de platos antiguos y vieja mesa redonda con mantel de ganchillo, parecía un espacio recatado y tranquilo de inicio. De repente el ambiente despierta con el firme rasgueo del charango acompañado de animadas letras. Vestido con una ajustada camisa blanca, gran hebilla de cinturón y jeans oscuros, su cabello negro azabache cayendo sobre sus hombros, Saxoman cierra los ojos y profundiza a la melodía de su canción. Canta acerca de su abuela, fallecida recientemente. La letra ""Amo tanto a mi mamá"" es sencilla pero genuina. Este vaquero latino es el talentoso y querido artista boliviano Americo Estévez Roman, más conocido como Saxoman. Nacido en La Paz en 1971, Americo es de una familia de músicos. Su tío escribió la famosa canción ""Collita"" sobre su esposa en la década de 1950. Americo comenzó a tocar la batería con su banda, Los Casanovas, que estaba compuesta por sus tíos. Experimentando con diferentes instrumentos, finalmente tocó el saxofón en la calle para ganar un poco dinero para mantener a su familia. Fue visto y presentado por el programa de televisión Gigavision.

El director del programa lo llamó en broma Saxoman, y el nombre se quedó. Saxoman detiene su canción y nos lanza una explicación sobre cómo aprendió a tocar el charango. Quería crear un video de Youtube para dar la bienvenida al Papa Francisco a Bolivia. '¿Pero quién iba a tocar el charango para mí?', se preguntó. “¡No sé tocar el charango! ¡Nunca lo había tocado en mi vida! ”Saxoman no pudo encontrar ningún voluntario, pero un amigo se ofreció a prestarle un charango, solo por una hora. '""¡¿Una hora ?!"" Dije: ""Está bien, está bien"" "". Aprendió a tocar el instrumento en 20 intensos minutos. El video del Papa de Saxoman encarna su determinación. Experimentado, divertido y seductor, hace sonreír a quien lo mira. En un minuto Saxoman está tocando el charango con la cara del expresidente de Bolivia Morales en la esquina de la pantalla, al siguiente está volando por el universo, al cual describe como un estilo “rock lento”, destacando el sonido del charango, y su hijo Gabriel en la batería. Dice que hizo muchos amigos a través del video. Impresionantemente, todo fue filmado en un teléfono antiguo. A través de sus videos, Saxoman ofrece una visión de su fantástico mundo situado en Bolivia. Sin duda es un paceño orgulloso, como se lo ve en su video titulado 'La Paz Ciudad Turística ', canción que lleva de fondo a la ciudad mencionada en su estado natural nocturno.

Miles de luces parpadeando en el video dan una sensación de expansión y vitalidad de la ciudad. Saxoman canta sobre el majestuoso Illimani, la montaña icónica que domina la ciudad. Junto a sus hijos, forman una nueva versión de Los Casanovas, con los cuales lanzaron esta canción que comienza con tambores que acompañan a una flauta andina, convirtiéndose en un rock lento que también enlaza con diferentes estilos musicales bolivianos. Finalmente, Saxoman se engancha la guitarra al hombro para un solo bastante impresionante para los espectadores. La pasión de Saxoman por la música es incomparable. Dice: ""Me enamoro todos los días"", y es este amor el que lo inspira a escribir sus canciones. Saxoman tiene 45 años, pero ""con el alma de un niño"", agrega.

La fantasía de todo niño es ser un superhéroe, por lo que Saxoman y su banda se describen a sí mismos como personajes ficticios que portan y tocan sus instrumentos como armas mortales para luchar contra los malos. Saxoman no gana mucho dinero con su música; su único ingreso proviene de la música callejera que es apreciada por transeúntes. A pesar de esta creciente fama, quiere mantenerse fiel a sí mismo y a sus raíces. Ha aparecido en la televisión boliviana, incluida La Revista del canal UNITEL, y en el periódico La Razón. A pesar de esto, su principal objetivo es entretener a niños y adultos por igual, al mismo tiempo que hace realidad sus sueños más audaces y “locos”. Sin importar cuán grande sea su fama futura, Saxoman dice que seguirá tocando música para la gente en las calles de los distritos de Barrio Chino, Miraflores y Zona Sur de La Paz. No solo Saxoman es un hombre del pueblo, sino que es un hombre que Bolivia aprecia. Vibrante, emocionante y decidido, representa a la perfección a La Paz y sus habitantes. A través de su música, Saxoman comparte su espíritu paceño con el resto del mundo. Se divierte con todo lo que le gusta y le fascina, ya sean los superhéroes, la magia e incluso los pitufos. Su música te invita a ver la vida como él, de una manera única.

Download

Download