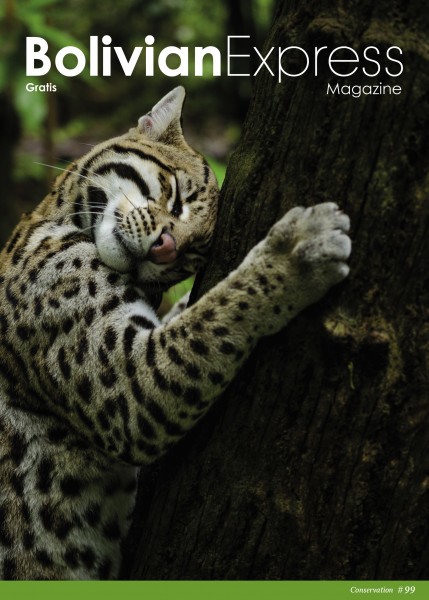

Cover: Nicole Marquez Aguirre @niksmrqz

CONSERVATION

On 7 October, the Reuters news agency reported that heavy rains helped extinguish fires in the Bolivian Amazon after two months of unrelentless burning. Fires in the Amazon are a yearly recurrence that don’t usually cause much concern, but this year they grew out of control: 5.3 million hectares burned this year in Bolivia – 4 million hectares in the Santa Cruz department alone – an area roughly the size of Costa Rica. Reasons for this year’s catastrophic fire season include dry atmospheric conditions exacerbated by rising temperatures, policies that encourage farmers and landowners to employ slash-and-burn land-clearing methods, and the lack of regulation and monitoring.

A 2009 report from Oxfam International alerted us that ‘Bolivia can expect five main impacts as a result of climate change: less food security; glacial retreat affecting water availability; more frequent and more intense “natural” disasters; an increase in mosquito-borne diseases; and more forest fires.’ Ten years later and that prophecy has come to pass. Glaciers are melting faster than ever, forests the size of small countries are burning, ecosystems are being displaced and whole species are in danger of becoming extinct.

The Amazon fires may have receded, for now. Our indignation will undoubtedly be piqued again when the next climate-change-related tragedy pops in our feed. It is very easy to get distracted and forget what has just happened with all this going on. We feel a sense of helplessness, anger and despair when seeing the news, and we look for someone to blame and we replace plastic straws with metal ones. At the 2019 UN General Assembly, Bolivian President Evo Morales blamed capitalism for our sorry state of affairs. ‘The underlying problem lies in the model of production and consumerism, in the ownership of natural resources and in the unequal distribution of wealth,’ he said. ‘Let’s say it very clearly: the root of the problem is in the capitalist system.’

As true as this may be, this critique doesn’t offer any solutions. Recently, The New Yorker published an essay titled ‘What If We Stopped Pretending?’ ‘The climate apocalypse is coming,’ it argued. ‘To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it.’ So let’s not pretend: It is too late – we will never get back the glaciers that are melting in our lifetimes, and we won’t be reviving extinct species any time soon – but we can still do something about it. We may not know how to do it yet, but we can’t stop trying.

WILDLIFE SANCTUARY

COMUNIDAD INTI WARA YASSI

Description: CIWY is a Bolivian non-governmental organisation dedicated to rescuing, caring for and rehabilitating sick, mistreated and abandoned wildlife since 1992. Nowadays they run three Wildlife Sanctuaries in Bolivia where they care for over 400 rescued animals with a team made up of professionals and the support of Bolivian and international volunteers.

Website: www.intiwarayassi.org

Photo:Nicole Marquez Aguirre

---

SHOPPING

Description: Under the concept of upcycling La Negra offers infinite possibilities of designs engraved in glass. The project gives a new life to this fantastic material, contributes to recycling become a habit and at the same time creates some art!

Contact: +591 78932931

Photo: Jean Carlo Salinas @jeanco666

---

ECO HOTEL

THE BIOTOPE BOUTIQUE HOUSE

Description: Located in the milder weather of La Paz city’s southern district, this prototype for sustainable living provides a comfortable and cozy place to stay. The house features a unique vertical greenhouse, it has four shared areas, seven comfortable en-suite double rooms and one self-contained flat with its own kitchenette. Adjoining the house is the Bolivian Box cafe, which is open to the public Monday-Saturday 8 am-7 pm.

Address: Calacoto, 24th street #184

Contact: +591 67180533

Photo: The Biotope Boutique House

---

RESTAURANTS

CHALET FLOR DE LECHE

Description: The best place for cheese lovers! It is a rustic and ecological restaurant that delights your palate with European-style cheeses made by themselves with the best highland milk. You can choose between fondue, raclette, cheese board and pizza in addition to its delicious variety of desserts, wines and craft beers.

Address: Achocalla, Sojsana #8

Opening hours: Saturdays and Sundays 12:30 - 16:30

Reservations: +591 2 2890011 - +591 72066011

Website: www.flordeleche.com

Photo: Flor de Leche

---

ECOTOURISM

MADIDI JUNGLE ECOLODGE

Description: This is a low-impact rainforest eco-venture created and sustained 100% by indigenous people from the heart of Bolivia’s Madidi National Park, they are committed to sustainable ecotourism that is carried out in a manner which is respectful to the flora and fauna. Their staff incredibly knowledgeable and passionate about the Amazon, offering highly personalized tours in order to create a memorable experience for all their visitors.

Website: www.madidijungle.com

Contact: +591 71282697 (Eng) +591 73530973 (Esp)

Photo: Madidi Jungle Ecolodge

---

SKIN CARE

BYO COSMÉTICA NATURAL

Description: Byo is a natural cosmetic venture that offers several product lines for personal and skin care. Its creams, tonics and shampoos combine natural extracts with essential oils that nourish our skin and do not harm the environment.

Address: Guachalla street #452

Opening hours: 9:00 - 13:00

Contact: +591 74021034

Photo: Byo Cosmética Natural

---

BUSINESS

INNOVAPLAST

Description: Innovaplast is a company dedicated to reduce pollution levels through plastic recycling and to create awareness and ecological culture. In 4 years they won 12 awards thanks to their commitment to the environment. Among its eco-friendly products, they offer oxo-biodegradable bags made with 100% recycled plastic that degrade in 5 years.

Contact: +591 71521721

Website: www.innovaplast.org

Photo: Innovaplast

This award by the International Taste Institute, a world leader in food and beverage evaluation, is the highest recognition this Bolivian national product has achieved.

Singani Casa Real celebrates a new international certification. The national drink of Bolivia has been accredited with a Superior Taste Award that acknowledges quality and recognises the best products annually. Singani Casa Real was evaluated by a panel of experts from the International Taste Institute, a world leader in food and drinks evaluation and accreditation based in Brussels, Belgium.

‘Each recognition fills us with pride and motivates us to continue working for Bolivia,’ said Casa Real’s general manager, Luis Pablo Granier. ‘This achievement certifies the quality of our singani at home and abroad. Our task as leaders in the category is to continue promoting singani in Bolivia and in the rest of the world.’

‘The per capita consumption of singani as the national drink of Bolivia still has to grow when compared to other regional national drinks such as pisco in Peru and Chile, cachaca in Brazil and tequila in Mexico,’ Granier added. ‘That is our mission.’

Since 2005, the International Taste Institute has conferred its Superior Taste Awards. The institute’s more than 200 food and beverage experts are members of the most prestigious chef and sommelier associations in the world. To receive accreditation, each product takes part in a strict evaluation process.

To achieve this international certification, Singani Casa Real was subjected to a blind test by a jury that didn’t know the name or the origin of the brand and product and only received a brief description of the product category.

The singani was evaluated for its organoleptic qualities based on five criteria: first impression, vision, smell, taste and final sensation. Each expert analysed and qualified the singani in private without communicating with the other tasters.

ABOUT CASA REAL

Casa Real is the preferred brand in the singani market, a drink recognised internationally as a national symbol of Bolivia. In 2009 it won the award for Best Distillate in the World. The Granier family has preserved a winemaking tradition for more than four generations, producing singani with the highest levels of innovation and technology in the Tarija region since 1925. The winery, located at more than 1,850 metres above sea level, benefits from a warm climate, pure air and intense light, resulting in ideal conditions to grow the grapes and obtain a product of high quality. Singani Casa Real is now conquering the North American market through an exclusive brand, Singani63.

Photos: Manuel Roca

Climate Change from Chacaltaya

Dr. Marcos Andrade recalls a satirical television show he once watched whereby viewers were humorously reassured, ‘Don’t worry about the environment; scientists will solve the problem.’ Jokes aside, Andrade, Director of the Laboratory for atmospheric Physics at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA) in La Paz, coordinates a group of climate scientists that have gathered at a unique Bolivian observatory, precisely with the aim of better understanding climate change.

Chacaltaya mountain is located 28 kilometres north of La Paz. It was once the site of Bolivia’s only ski resort, which was – and would still be today – the highest ski resort in the world. As of 2009, the Chacaltaya glacier had almost entirely melted, forcing the resort to close. Although the mountain’s ski-lift is now inactive, life in Chacaltaya goes on. Scientists travel up and down the mountain on a weekly basis to work at a laboratory that began its life as a weather station in 1942. At the end of the decade, the first experimental evidence of a subatomic particle known as a pion was uncovered at the Chacaltaya observatory. Two Nobel Prizes for Physics were subsequently awarded for the discovery. ‘Thanks to Chacaltaya,’ Andrade explains, ‘the physics department [at UMSA] was founded.’ The site is now home to a cosmic ray research facility and one of the stations in the Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) network, which monitors the chemical composition and selected physical characteristics of the atmosphere. It seems appropriate that one of the observatory’s prime functions is to demystify the forces behind the mountain’s dramatic make-over.

The Chacaltaya Observatory is unique for two principal reasons.

Firstly, its location at altitude has proven to be a great advantage for monitoring atmospheric composition. It is the highest atmospheric observatory in the world, at 5,240 metres above sea level. At this altitude, the air surrounding the observatory typically belongs to an atmospheric strata called the free troposphere, which lies five to six kilometres above the Earth’s surface. Tropospheric measurements are particularly useful because certain elements live longer at this height than at sea level. Therefore, the Chacaltaya observatory is able to paint a more accurate global picture of atmospheric composition. No other observatory anywhere in the world can boast the ability to monitor our atmosphere at such an altitude. The second highest observatory in the world is the Nepal Climate Observatory (5,079 metres above sea-level). Inconveniently, the site is particularly difficult to access, and scientists have to hike for four to five days to get to the observatory from the closest airport. Yet, Chacaltaya is an hour drive away from the El Alto airport, making it the highest, most accessible atmospheric observatory in the world.

Secondly, Chacaltaya is unique for its surrounding geography. A quick glance at any world map reveals that there is more land mass in the northern hemisphere than in the southern hemisphere. For this reason, observatories in the southern hemisphere are rarer and more valuable. The various landscapes around Chacaltaya are also a cause for celebration: from the observatory’s location on the altiplano, the Pacific Ocean is approximately 300 kilometres away and the Amazon rainforest is 100 kilometres in the opposite direction. Andrade explains that this topographical diversity is extremely useful for studying the climate, as it enables researchers ‘to sample air masses coming from all directions.’ Again, this helps scientists develop a fuller picture of what climate change entails. Being so close to La Paz also means that researchers can easily detect the city’s emissions, from transport pollution to the fumes from biomass burning. ‘It’s as if you can see how the city is breathing,’ says Andrade.

For the reasons stated above, Chacaltaya plays an integral role in the GAW network. Andrade leads a team of 13 local researchers at the observatory, and they are supported by a group of experts from countries such as Germany, Sweden and France. Monitoring climate change across the world would be impossible without this level of international collaboration. In order to better understand our planet’s climate and the effects of human activity, scientists must work together to share the data they are collecting. Climate threats and climate trends can only be determined through maintaining consistent, long-term and global records. Andrade emphasises the importance that everybody involved in the process ‘follow the same protocols.’ Only in this way will all of the stations be able to compare their data over time. Chacaltaya has been collecting data for the past eight years, making it the longest-running climate record of any South American observatory at altitude.

The findings at Chacaltaya confirm that the Andean region is just as vulnerable to global warming as any other corner of the world. In the study Bolivia en un mundo 4 grados más caliente (‘Bolivia in a world 4 degrees hotter’), authors Hoffmann and Requena provide an alarming outlook on the impact of a gradual temperature increase across the country. The study claims that higher altitude regions such as the Andes are more likely to suffer from a rise in temperature. Mathias Vuille, a climate specialist from Switzerland, believes that the northern altiplano is likely to witness a temperature increase almost 1.5 times the global average. From an aesthetic standpoint, the retreating of the glaciers will irreversibly alter the classic postcard image of La Paz, and the city will eventually be shadowed by a naked Illimani. More importantly, the glaciers serve as a crucial source of water, acting as reservoirs for a country that has a longstanding history of droughts and water wars. Many researchers, Andrade included, are curious and fearful about what will happen when this vital source of water runs dry.

Yet, Andrade still has hope for the future. He recognises that atmospheric science and meteorology are undersubscribed fields of study in Bolivia, but he has a dream that one day the country will establish an interdisciplinary school or specialised university department in those areas. A stronger body of climate scientists would inevitably lead to a greater understanding of environmental issues, which would better equip Bolivia with the knowledge and expertise to face any forthcoming dangers caused by climate change. From a practical point of view, Andrade is aware that Bolivia ‘cannot convince everyone to cycle to work or be greener but [we] can reach a consensus about policies.’ It would seem that the power to spark an interest in the environment and to put a stop to harmful practices, such as deforestation and the burning of biomass, lies in the hands of policy-makers. Should any evidence be needed to justify the urgent and immediate need for global action against climate change, it can be found at the Chacaltaya observatory.

.

Download

Download