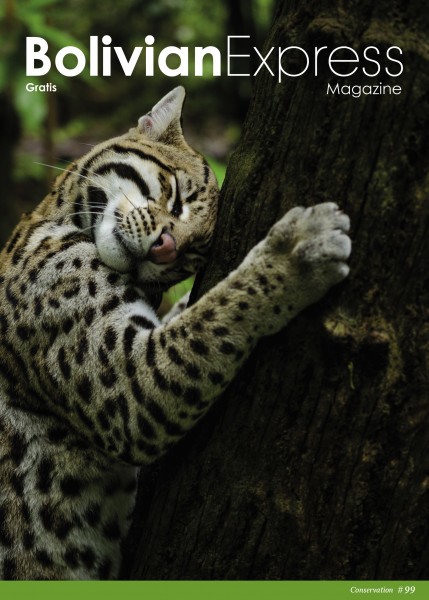

Cover: Nicole Marquez Aguirre @niksmrqz

CONSERVATION

On 7 October, the Reuters news agency reported that heavy rains helped extinguish fires in the Bolivian Amazon after two months of unrelentless burning. Fires in the Amazon are a yearly recurrence that don’t usually cause much concern, but this year they grew out of control: 5.3 million hectares burned this year in Bolivia – 4 million hectares in the Santa Cruz department alone – an area roughly the size of Costa Rica. Reasons for this year’s catastrophic fire season include dry atmospheric conditions exacerbated by rising temperatures, policies that encourage farmers and landowners to employ slash-and-burn land-clearing methods, and the lack of regulation and monitoring.

A 2009 report from Oxfam International alerted us that ‘Bolivia can expect five main impacts as a result of climate change: less food security; glacial retreat affecting water availability; more frequent and more intense “natural” disasters; an increase in mosquito-borne diseases; and more forest fires.’ Ten years later and that prophecy has come to pass. Glaciers are melting faster than ever, forests the size of small countries are burning, ecosystems are being displaced and whole species are in danger of becoming extinct.

The Amazon fires may have receded, for now. Our indignation will undoubtedly be piqued again when the next climate-change-related tragedy pops in our feed. It is very easy to get distracted and forget what has just happened with all this going on. We feel a sense of helplessness, anger and despair when seeing the news, and we look for someone to blame and we replace plastic straws with metal ones. At the 2019 UN General Assembly, Bolivian President Evo Morales blamed capitalism for our sorry state of affairs. ‘The underlying problem lies in the model of production and consumerism, in the ownership of natural resources and in the unequal distribution of wealth,’ he said. ‘Let’s say it very clearly: the root of the problem is in the capitalist system.’

As true as this may be, this critique doesn’t offer any solutions. Recently, The New Yorker published an essay titled ‘What If We Stopped Pretending?’ ‘The climate apocalypse is coming,’ it argued. ‘To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it.’ So let’s not pretend: It is too late – we will never get back the glaciers that are melting in our lifetimes, and we won’t be reviving extinct species any time soon – but we can still do something about it. We may not know how to do it yet, but we can’t stop trying.

Photo: Renata Lazcano Silva

Aiming to reduce single-use plastics

The plastic bag is ubiquitous in Bolivia and around the world. On average, a plastic bag is used once for no more than 15 minutes before it is thrown away. It then takes at least 150 to 500 years (or more) for that bag to degrade. The United Nations estimates that 10 million plastic bags are used globally every minute. In Bolivia, about 4 billion plastic bags are used each year, without considering other types of single-use plastics. So what are we doing about it?

The Union of Environmental Journalists of Bolivia (Unión de Periodistas Ambientales de Bolivia, or UPAB), a civil association founded in December 2008, has sponsored a bill to reduce and replace plastic bags. The bill’s objective is to ‘minimise the impact on the environment and ensure the sustainability of the life systems of Mother Earth through the gradual and progressive reduction and replacement of the use and production of plastic bags throughout the national territory.’ This bill, which was approved by the Bolivian Senate’s Environmental Commission in May 2019, was a collaborative effort that enlisted the input of government ministries, business leaders and other organisations to avoid any obstacles in its implementation after being turned into law.

While waiting for the full legislature to vote on the bill, an environmental education campaign, #DesembolsateBolivia (#UnbagBolivia), is rolling out across the country to unite schools, universities, businesses, markets, neighbourhoods and other entities under the common objective of raising public awareness about the impact of the use of single-use plastic bags, reducing their use and proposing ecological alternatives to plastic. Education is essential to motivate people to change their habits for more sustainable practices. The campaign has the support of the Bolivian Ministry of Education to involve the country’s education system. Furthermore, mass media and social networks are helping this initiative reach the public at large.

‘It is important that the country assumes clear environmental strategies,’ Carlos Lara, the president of the UPAB, says. ‘It has to prioritise the issue of the environment now and in the following years, because the environment is very sick and in serious danger.’ All the nations of this earth have to apply policies and regulations to protect the environment and protect their inhabitants, but we here in Bolivia must make our own first steps, change our habits and show by example the message of nature conservation to more people. Let's make a difference, day by day, decision after decision. Our planet is the only home we have. We are now facing the extremely serious global problems of pollution, deforestation and loss of biodiversity, among others. The good news is that we know what needs to be done. Now is the time to act.

“An Environmental Crisis is a Government Policy, Chiquitanía in Flames is a National Desaster”

Photos: Lauren Minion and Silvia Saccardi

Students take to the streets to demand climate justice

Fridays for Future is a climate justice movement created in August 2018 by Greta Thunberg, a Swedish activist who was then 15 years old. She decided to protest every Friday outside her country’s Parliament, demanding that authorities take action against climate change. Over the past year, Fridays for Future has grown, with up to 7 million young people taking to the streets across the globe to demand climate justice. La Paz, too, took part in the first-ever world strike for the planet on 15 March 2019.

The Bolivian Fridays for Future chapter has already organised four strikes, one information fair, one street clean-up and various conferences to tackle the issue of climate change. Starting with 150 attendees at its first protest, Fridays for Future now sees upwards of 600 people at its events in in La Paz, mostly students who are demanding that authorities react to this climate crisis.

When I began to understand the seriousness of the problems that we are facing, I felt a profound sadness and disgust. I couldn’t believe that we are living through the most serious crisis in history, and that those who should be finding solutions aren’t interested in this important task. Bolivia is among the countries most threatened by the climate crisis, and one of the 15 most biodiverse nations in the world; it is therefore vitally important that it be involved in this fight. As time passes, we come ever closer to the point of no return – that is, a global temperature rise of 1.5 degrees celsius. If this were to happen, life on earth as we know it would be in danger, including ourselves. This is a problem that concerns all of us, and, therefore, we all have to work together to resolve it.

Nina Py Brozovich is the founder and spokesperson for the Fridays for Future movement in Bolivia.

“We are the species in danger of extinguishing it all!!!!”

“This sign refers to the fire’s threat to animal species, including the Giant Armadillo”

“Let’s look after the lungs of our planet”

“Police forces prevent unrest by blocking connecting streets”

Photos: Amelia Swaby

Wildlife trafficking threatens the iconic jaguar

International illegal wildlife trafficking now threatens the extinction of many species native to Bolivia. Birds are the most commonly trafficked animal, with approximately 4,000 different species being traded worldwide. The Santa Cruz–based newspaper El Deber reported that the illicit trade has annual revenues of more than US$20,000 million, making it the fourth-most-lucrative illegal industry in the country (only trailing the trafficking of drugs, weapons and human beings). One of the major victims of Bolivia’s wildlife trafficking is the jaguar.

Poachers – who often work to supply to Chinese market, where there’s great demand for these feline beasts – kill and remove their prey’s fangs, which are then smuggled into the Asian market, where they are as valuable as gold or cocaine. There are merely 64,000 jaguars in the wild now, a number that has been dramatically decreasing, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Where before only the bones of jaguars were used for traditional Chinese medicine, the whole of the big cat’s body is now more lucrative, with smugglers boasting of the additional supposed health benefits of the jaguar’s tongue, penis and other organs. There are even luxury restaurants in China that sell jaguar meat as a delicacy. Some people display necklaces made jaguar as a symbol of status, sexual prowess and power. The Chinese mafia is even getting into the game and fuelling wildlife trafficking in Bolivia by expanding into the taxidetermology, medicinal-products and pet-trade industries.

Bolivia’s park rangers try to defend Bolivia’s 22 protected areas of national interest, but they are not enough. La Paz’s Página Siete revealed that the guards are overworked – often working for 24 consecutive days, followed by only six rest days – and exhausted, with insufficient equipment, resources and personnel, facing daily threats of hunters, drug traffickers and nature itself. Many only have temporary contracts with low salaries yet must protect 77,985 hectares. Since 1995, 16 have lost their lives whilst guarding the land and two remain missing. In 2015 the authorities promised to increase the number of personnel, but the situation has not yet changed.

Virginia Ossio, together with her husband Marcelo Levy, has devoted her life to care for animals rescued from the illegal trade, and now is an official voice in Bolivia regarding environmental conservation and the illegal trafficking of America's big cat. The director and founder of La Senda Verde, a wildlife refuge in Coroico in Bolivia’s Yungas region, Ossio said that the trafficking epidemic of jaguar cubs first came to her attention in 2014, after the Bolivian postal service seized over 190 jaguar teeth bound for China (with many more believed to have been trafficked undetected). Jaguar mothers had been slaughtered for their fangs and body parts, and their cubs became a valuable ‘by-product’ destined to be sold as pets. Further alarm bells sounded when buyers were overheard on the radio by the World Conservation Society boasting about the prices they had been paid for jaguar fangs and body parts.

According to Bolivian journalist Roberto Navia Gabriel, this dire situation has only grown worse since 2014. In the tropical municipality of Sena, in the Pando department that borders Brazil, traffickers pay US$150 to US$400 for each jaguar fang, depending on its size. By the time the fang reaches China, it can sell for as much as US$2,500, a tenfold increase. Between 2013 and 2016, 380 jaguar teeth were seized by Bolivian authorities, and the trade has only grown since then. From April to September in 2016, the Bolivian Forestry and Environmental Police seized a total of 181 jaguar fangs destined for China.

Many hunters refer to these cats as tigers. When approached by Chinese buyers, they are often shocked by the prices offered; one hunter revealed to Página Siete that he was surprised that someone would pay him for fangs that were worth nothing to him.

‘We need to change the system and way of living,’ said Ossio. ‘Greed is harming the planet. People just don’t understand their impact.’ She suggested that the Bolivian government has had very little effect as environmental conversation is not currently a priority and poaching is a crime which warrants little to no punishment. Despite being clearly illegal, the risks for hunters and traffickers are relatively low. To tackle this, Ossio says, ‘We need to pressure, ask for more [jail] time’ and make the consequences more severe. ‘We are making it too easy for [traffickers],’ Ossio adds. ‘We are handing our ecosystem over to them.’

Ossio said that, despite her and her colleagues’ best efforts, sanctuaries like La Senda Verde are not the solution to the problem. Only one out of every ten animals taken out of the jungle survive. Prevention is the only way to solve the trafficking problem.

Jaguar cubs that come into Ossio’s care are extremely vulnerable and face numerous health problems. They are reliant on mother’s milk for the first three months of their lives, and without it they suffer bone, joint, digestive and immune problems. This makes them extremely hard to raise in captivity, and many die despite all efforts to save them.

As a result of the recent dramatic increase in animal trafficking, La Senda Verde’s animal population has more than quadrupled in the past five years. It now houses more than 800 rescued animals, from howler monkeys and macaw parrots to Andean spectacled bears and a vast array of reptiles.

‘Hopefully we will disappear and give the animals a chance.’

—La Senda Verde’s Virginia Ossio director and founder

Whilst Ossio says that ‘we are opening the door to traffickers… We are offering them a buffet of options,’ she thinks it will be organised social movement movimientos ciudadanos that will drive necessary change. Local people working against trafficking is the only way to stop it. Her vision is educational, with prevention being a key focus. The Bolivian government has passed some legislation that has formalised certain protections for the jaguars and criminalises the trade. Those who incite, promote, capture or commercialise wild animals categorised as vulnerable face up to six years in jail. However, Ossio’s perspective is more radical and focuses on education to raise awareness of the wildlife-trafficking trade and its impact. As part of this, La Senda Verde offers free entrance to teachers and students from Coroico and charges a reduced entrance fee to Coroico’s 3,000 families to promote safe interactions and mutual understanding with the animals. Ossio strongly believes that the country’s youth are driving Bolivia’s consciousness, so the country must invest in them to ensure a future for its jaguars.

But the scale of the wildlife-trafficking in Bolivia makes it hard for Ossio to be an optimist. ‘Hopefully we will disappear and give the animals a chance,’ she says. Bolivia’s jaguars need to be left in peace.

Download

Download