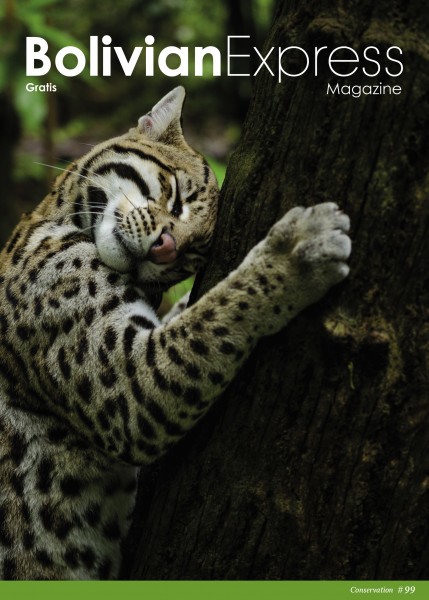

Cover: Nicole Marquez Aguirre @niksmrqz

CONSERVATION

On 7 October, the Reuters news agency reported that heavy rains helped extinguish fires in the Bolivian Amazon after two months of unrelentless burning. Fires in the Amazon are a yearly recurrence that don’t usually cause much concern, but this year they grew out of control: 5.3 million hectares burned this year in Bolivia – 4 million hectares in the Santa Cruz department alone – an area roughly the size of Costa Rica. Reasons for this year’s catastrophic fire season include dry atmospheric conditions exacerbated by rising temperatures, policies that encourage farmers and landowners to employ slash-and-burn land-clearing methods, and the lack of regulation and monitoring.

A 2009 report from Oxfam International alerted us that ‘Bolivia can expect five main impacts as a result of climate change: less food security; glacial retreat affecting water availability; more frequent and more intense “natural” disasters; an increase in mosquito-borne diseases; and more forest fires.’ Ten years later and that prophecy has come to pass. Glaciers are melting faster than ever, forests the size of small countries are burning, ecosystems are being displaced and whole species are in danger of becoming extinct.

The Amazon fires may have receded, for now. Our indignation will undoubtedly be piqued again when the next climate-change-related tragedy pops in our feed. It is very easy to get distracted and forget what has just happened with all this going on. We feel a sense of helplessness, anger and despair when seeing the news, and we look for someone to blame and we replace plastic straws with metal ones. At the 2019 UN General Assembly, Bolivian President Evo Morales blamed capitalism for our sorry state of affairs. ‘The underlying problem lies in the model of production and consumerism, in the ownership of natural resources and in the unequal distribution of wealth,’ he said. ‘Let’s say it very clearly: the root of the problem is in the capitalist system.’

As true as this may be, this critique doesn’t offer any solutions. Recently, The New Yorker published an essay titled ‘What If We Stopped Pretending?’ ‘The climate apocalypse is coming,’ it argued. ‘To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it.’ So let’s not pretend: It is too late – we will never get back the glaciers that are melting in our lifetimes, and we won’t be reviving extinct species any time soon – but we can still do something about it. We may not know how to do it yet, but we can’t stop trying.

Passiflora Madidiana Especie Nueva - “The Madidi Passionflower is an endemic species (one that can only be found in this region)”

Images: Courtesy of Alfredo F. Fuentes Claros from The National Herbario of Bolivia

The biodiversity of the Madidi National Park and its importance to Bolivia

The Madidi National Park, established in 1995, is one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. The park itself covers nearly 2 million hectares and is home to 60 percent of Bolivia’s rich plant life and 66 percent of the country’s extensive wildlife. It used to be a relatively unsung beauty, until it was popularised by Yhosseph Ghinsberg’s novel Jungle, which was later turned into a film starring Daniel Radcliffe. This brought many more tourists to the area to appreciate its unique habitats and breathtaking wildlife.

However, the park was seriously damaged by forest fires earlier this year, which destroyed 300 hectares of dry woodland habitat in the area. Additionally, some areas of the park near the Beni River are also threatened by mass industrialisation following government proposals for the construction of a hydroelectric power station. With these looming threats in mind, BX spoke with biologist Alfredo F. Fuentes Claros, a researcher with the National Herbarium of Bolivia and the Missouri Botanical Garden. He has long worked at conservation projects in the region, and recognises how vitally important it is to protect this incredible part of the world.

The Madidi National Park encompasses a wide range of habitats, including Andean high grounds, low-lying tropical Amazonian rainforest, the aforementioned rare dry forest, and both mountain and swamp savannas. These sweeping habitats collectively result in the rich biodiversity of the region. According to Fuentes, the park’s varying altitudes make way for disparate temperatures and levels of rainfall, which contribute to the abundant wildlife and plant species that are present, some of them quite rare. Fuentes said that there are two categories of these rare species. The first category comprises endemic species that require a very specific habitat to survive, and which are therefore only present in the park’s specific environment. The second category comprises species that can live in a number of habitats, but due to external factors, including human activity and climate change, their populations are no longer stable. Madidi is home to a large number of rare plants and animals from both categories.

Vegetación altoandina húmeda - “Shepherding Llamas across the higher Andean regions within Madidi National Park”

Collaborative projects have been established throughout the park to monitor climate change in the region, track rare species and keep scientific records of recently discovered species. These projects were established principally between education institutions in the United States, including the Botanical Garden of Missouri, and the National Herbarium of Bolivia. Specimens are collected regularly from previously defined allotments in the park. Fuentes said that ‘the main change, seen as a result of climate change, is that as the temperatures heat up, the species that are used to the original colder temperatures are ascending up into the Andes.’ In the past, Fuentes said, there were considerable delays in the collection and identification of these specimens, due to the Bolivian government’s inaction in renewing permissions for the continuation of the projects. There were also other delays in granting permission to send many species off to the Botanical Gardens of Missouri to be identified. Ultimately, these issues were resolved, and the Bolivian government now provides some financial support.

Recent news headlines show that the Madidi National Park has been affected by natural disasters and the consequences of human activity. The park not only suffered a considerable loss of land earlier this year to forest fires, it’s also under threat from the Bolivian government's industrial development planning. Although proposals for the construction of a major hydroelectric plant along the Beni River have been approved, its construction was postponed after a nationwide outcry at the potentially damaging project.

The importance of Madidi National Park is not only limited to the animal and plant species that it boasts; it also hosts a sizable indigenous population. The park houses and provides invaluable resources to 31 family communities living in the area, from four main historical indigenous groups, including the Tacana, San José de Uchupiamonas, the Lecos de Apolo and the Lecos de Lareceja. The principal objective of the conservation projects is to ensure the sustainability of resources so that these communities can continue to flourish in this region. Fuentes said that there were some initial conflicts with the local indigenous populations back when the projects began; however, he said, they were ‘more for the political situation than the work of the scientists… In the beginning, [the indigenous] didn’t allow us to enter their territory, but after explaining ourselves and our work well, they let us in.’ These indigenous groups now receive an annual scientific report, and they keep track of plant species in their own regions. Now, Fuentes said, ‘there is always a very good collaboration.’

Nativos Tacana Tejiendo - “Some indigenous Tacana people building baskets out of palm leaves”

Many of these indigenous people are also involved in the park’s vibrant tourism industry, having set up numerous ecolodges with tours aimed at increasing awareness without damaging or unsettling the region’s wide variety of flora and fauna. Contrary to what one might think, Fuentes also encourages tourism in the region. ‘You won’t learn anything until you experience it first hand,’ he said. The industry itself is well established and sustainable, with three-day tours that include cooking locally sourced ingredients every day and minimalist accommodations within the forest and savanna. Fuentes encourages people who are interested in visiting to research different tourism companies to ensure that their excursions won’t be detrimental to the park’s exquisite wildlife.

Conservación Turismo - “Locals navigating the river, surrounded by diverse tropical rainforest”

There’s an indisputable vitality of Madidi National Park that can be witnessed through the flora, fauna, indigenous people, sustainable industry and invaluable resources is contains. Fuentes said that it is the incredible array of plants that are responsible for this. ‘Plants give us practically everything that we need in life,’ he said. ‘They give us fresh air, they give us water, they facilitate our infrastructural needs, they prevent climatic disasters. They provide us with wood for construction, they give us fruit, medicine, and they are vital for the continuous development of indigenous nations.’ The Madidi National Park presents us with a positive and beautiful example of a successful ecosystem with a stable conservation project surrounding it. It is vital that this biodiverse region remains respected and protected, and the relationship with nature within the park remains harmonious. The continuous collaboration of scientists, indigenous people and the tourism industry can ensure that Madidi National Park remains one of the most biodiverse areas on the planet.

Bosque Húmedo - “The humid tropical rainforest in Madidi National Park”

Wildlife Sanctuary Ambue Ari up in flames. Ph: Raquel Izquierdo Jacoste

Images: Courtesy of Inti Wara Yassi

A look into the consequences of extreme forest fires caused by chaqueos

Bolivia has this year witnessed an astonishing number of forest fires, with over 4 million hectares of woodland having been burnt across the country, 2.9 million of which were concentrated in the Chiquitanía region. Starting in May and escalating at an alarming rate from the beginning of August, the fires in Chiquitanía have ceased for the time being, owing to torrential rain. Despite the welcome downpours, one thing they cannot do is wash away the impact of deforestation on the rapidly expanding agribusiness in eastern Bolivia.

Various volunteer organisations offered to help bring the fires under control, thereby providing a short-term solution to this human-made disaster. One such example is a student-run volunteer firefighter group called ‘Los Mirmidones.’ Mainly comprised of biology students from Universidad Mayor de San Andrés in La Paz, the group set about tackling the fires first-hand, with few resources at their disposal. At an event that sought to recruit new volunteers, the students were made fully aware of the potential risks involved, and it was made clear that individuals had previously lost their lives, highlighting the very real dangers of the situation. Most, however, returned with a sense of pride in the knowledge that they had fought for the rights of Pachamama.

When asked what Pachamama means to him, Bruno Parada, a student from the Biology faculty and volunteer in the Bolognia forest, said, ‘Pachamama is Mother Earth, the creator of life. It’s a way of conserving nature and culture.’ He goes on to say that this is a belief shared among many Bolivians, but that attitudes can vary across urban and rural areas. ‘Bolivia lacks environmental awareness. It’s a topic that is not very well known or understood. People are more interested in other things. They don’t really understand what it means to look after trees or wildlife or why you shouldn’t hunt animals, because they don’t understand how they could be affected. In urban areas, there is a greater awareness, but that’s because there is more information available.’

The smoky aftermath of the blaze. Ph: Raquel Izquierdo Jacoste

That sentiment is shared by Milli Spence, Director of Communications for the Bolivian organisation Inti Wara Yassi, which has three wildlife sanctuaries across Bolivia. ‘There's still a huge amount of education that still needs to happen, not just in Bolivia but around the world, but it takes a long time. When there is a multitude of other issues going on, environmental concerns can fall down on the list, even though they should be given a lot more priority, when other needs aren't being met or there are other issues going on in society.’

One of the organisation’s wildlife sanctuaries, Ambue Ari, located in Santa Cruz department, was one of the many areas affected by this year’s fires, causing thousands of animal and plant species to be lost. The park was affected by several fires in mid-September, resulting in a 10-day stint to combat them. Staff and volunteers were pushed to their limits, taking it in turns to stay up during the night and keep a watchful eye on burning logs for fear of the fire spreading. ‘One particular member of staff was out there for two and a half days straight. I could not believe his stamina, and we reached a point where everyone was so physically drained that we desperately needed sleep to regain energy to then continue fighting.’ Workers at the park teamed up with firefighters from the local municipality and volunteers from Cochabamba and the neighbouring town of San Pedro to combat the ferocious flames. Spence confirmed that Ambue Ari used to be connected to the surrounding forest, but the park now resembles an island of protected species, gradually decreasing in size.

The fires are almost always caused by unmonitored chaqueos spiralling out of control, having been started by neighbouring landowners seeking to clear their land. While it cannot be denied that chaqueo is an efficient means of clearing land, much more needs to be done to control how and when it is carried out. Spence says, ‘Ideally, people would refrain from burning land when it's 38 degrees Celsius and there are 20 kilometre per hour winds, or even when there are lower wind speeds but very high temperatures. If the conditions weren't so severe, the fires could be controlled more easily. But if you light a match on exceptionally dry land on a hot day with high wind speeds, it's going to burn very quickly.’ She adds, ‘At the moment it's being allowed, and there are no real restrictions as to how and when or if every farm wants to burn on exactly the same day there is no rule saying you can't or you need to coordinate. Having more guidance, more awareness and more education about when you should and shouldn't be burning should help reduce the risk.’

Two volunteers at Ambue Ari spraying charred logs to extinguish the flames. Ph: Gonzalo Choque

Chaqueo is a technique that has been used for centuries by farmers across the world. It is naturally carbon-neutral when used in moderation. But international influence, the increased pressures of fast-paced production and the adoption of a new law allowing slash-and-burn practices have all contributed to the method being overused. Sadly, Bolivia’s deforestation rate more than doubled between 2002-2017. Despite the country tackling illegal deforestation, the legalisation of slash-and-burn agriculture has meant that the overall rate of deforestation continues to rise.

The biggest driver of deforestation in Bolivia is agribusiness, particularly the development of soya and sugar cane plantations. Between 40 and 50 percent of Bolivian forests are owned by foreign powers, who burn large areas of land in the production of biofuels. Pablo Solón, Executive Director of Fundación Solón, comments that there are currently three main drivers behind the use of chaqueo: the increased development of biofuels, Bolivia’s desire to export meat to China and legislation that facilitates the burning of forestland. For example, if a company illegally burns one hectare of land, it must pay a fine of US$46, which is negligible enough to incentivise investment in the Bolivian dry forests. According to Solón, ‘Chaqueo is not traditionally practiced until the arrival of the rainy season.’ But now, forests are being burnt on a mass scale during the dry season, which some are calling ‘el mal-chaqueo.’

Measures have been put in place to control the fires, and parks such as Ambue Ari are becoming better equipped to tackle the flames thanks to donations of equipment, improved fire training and the development of water systems to make it easier to extinguish the fires. One of the most effective ways of combating the fires is to improve communication among local farmers, making it easier to pre-empt potential fires and thereby manage the risk. Climate change is aggravating the scale of the fires year on year, and if attitudes and methods do not change soon, the incidence of uncontrollable forest fires will continue to rise, ultimately destroying the habitat of species endemic to Bolivia.

An injured armadillo found beneath the ashes. Ph: Wilber Antonio Rasguido

Solón believes there are alternatives. ‘Bolivia needs to move towards an Amazon free from forest fires. There are other methods we could opt for. Instead of burning, we could cut down trees and clear the forest floor. That would require more work and greater effort, but it runs less of a long-term risk. Not all countries use slash-and-burn to clear land.’ He also stresses that a human kind without nature would be condemning itself and that in order to resolve the issue, we should move away from the anthropocentric society we currently live in and replace agribusiness with agroforestry, a form of farming that complements rather than exploits nature.

Society is only now coming to terms with the damage caused by slash-and-burn techniques and the unsustainable growth of agribusiness. By threatening biodiversity and several plant and animal species found only in the region, the burning of the dry forest is a human-made disaster with drastic consequences for human life. Using nature for our economic gain is having an effect on the number of wildfires in Bolivia. It is now time for the country to find alternatives to chaqueo, or learn how to manage and prevent the risks associated with wildfires through adopting adequate laws and regulations.

Photos: Nicole Marquez Aguirre

The Bolivian Amazon’s Ambue Ari wildlife sanctuary

My arrival at the Ambue Ari wildlife sanctuary, or ‘the park’ as the volunteers call it, began as a journey in search of a place where I could disconnect from city life and help others. It became a place that changed my life, where I connected with other volunteers, the animals and the nature surrounding us.

Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi (CIWY) has three centres in Bolivia that work for the protection of wildlife, rescue animals from illegal trafficking and educate the public about the importance of respecting the ecosystem.

The first thing one notices when arriving at the park is the dedication, respect and affection the centre and its staff have for each of the animals. Even deceased animals are commemorated with the ‘tree of memory.’ The facilities are basic, but volunteers quickly find that with a mosquito net, some tape and food, they have everything they need.

At first, like many others, I didn’t find it easy. I made mistakes and I felt out of place. It took about two weeks, with the constant support and help from the experienced staff and volunteers, for me to feel completely immersed and connected with my surroundings.

The work was hard but the reward was enormous. We worked six days a week, from six in the morning till six at night, taking breaks only to eat. We worked with vulnerable animals, many rescued from dire situations, and rehabilitated them physically and psychologically to a better and fuller life. This also entailed endless hours of fun for them, and for us. The daily routine is established according to each animal’s needs, so despite following a strict schedule, every day turned out different for us. After all, this is the Bolivian Amazon, and the jungle is constantly changing. There were wild animals inside the park, and the behaviour of the rescued animals varied depending on the surroundings and the volunteers present.

The work of the Inti Wara Yassi community is essential for the conservation of endangered species in Bolivia. This work couldn’t be done without the help from the volunteers who give their best in each situation with effort and good will, whether they are building new enclosures to provide better comfort to the animals, keeping the shelter clean or even putting out fires in the dry season.

My time at Ambue Ari was by far one of the greatest experiences of my life – and one of the hardest. During these two months I ended up connecting with the animals and nature, and with the other volunteers who came from around the world. I miss the Amazon rainforest, and I fondly remember how magnificent it is with its torrential rains, nocturnal sounds, and the wildlife and the people who live in complete sync with their surroundings.

Nicole Marquez Aguirre, a La Paz–based photographer, volunteered for two months at the the Ambue Ari Park, a wildlife sanctuary owned and managed by Inti Wara Yassi. Learn more at intiwarayassi.org

Download

Download