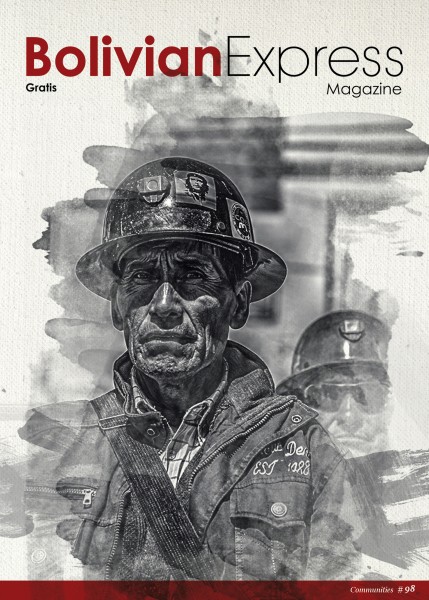

Cover: Jaime Cuellar Imaña @jcuellar18

COMMUNITIES

The Amazon fires destroyed over 4.2 million acres (1.7 million hectares) of Bolivian rainforest since 15 August. This number doesn’t take into account the fires in Brazil and Paraguay and what is still burning today. Man-made catastrophes such as these make us reflect on ourselves, on our individual lifestyle choices and on how we stand as a species. But ultimately, it makes us react as a whole, as a community; it reminds us that we are all connected and that this connection can be felt from across continents.

This issue focuses on communities, groups of people bound by common attitudes, interests, and goals: family, neighbours, friends, members of a political party, vegans and more. Our community helps us survive and gives us a sense of belonging and identity, but the nation-state is in decline, religions are losing their appeal and, filling that void, new global communities have arisen: digital worlds, chosen ideologies, foreign cultures.

To illustrate this, in the most remote corners of the Bolivian countryside one can find images of Korean pop stars on the notebooks of children who can reproduce choreographies and sing along to Korean pop songs. This may be a symptom of Bolivia suffering from the same disenchantment with authority figures as the rest of the world, but it mostly means that Bolivia is very much a part of the global community.

Veganism is another trend that has reached Bolivia. Perhaps veganism is more than a simple fad, as it operates as a secular religion by promoting a way of life and philosophy. The popularity of plant-based food in La Paz is not just a phase; the movement – and similar conscious-food initiatives – was able to establish itself because of how well it fits in with the local understanding of the world. We may be witnessing a new type of syncretism taking place in which the local and the global intertwine to create something new.

If Bolivia is part of a global community, family remains the chore of the Bolivian identity. The family unit is what defines and forges us. But it doesn’t have to be the only community we belong to. Now one’s community is not just immediate family and neighbours; our community is where we want it to be with the people we choose to be around.

MUELA DEL DIABLO

Description: This rock formation in the south of the city is one of the most iconic sights in La Paz. Muela del diablo means ‘devil’s molar’ and its shape is what remains of an extinct volcano. It is an accessible hike from the city which can take from 2-3 hours to the full day..

How to get there: Take the minibus #922 or #207 to Los Pinos-Pedregal. Once in Pedregal you can walk or take a taxi to Chiaraque, the little town at the bottom of Muela Del Diablo. From there it’s a short hike uphill. It is possible to climb the Muela but this should be attempted with care and only under the right conditions.

Photo: Jaime Cuellar Imaña

---

HOSTEL

LAS OLAS

Description: On a hill overlooking Lake Titicaca, Hostal Las Olas offers individually designed suites using as many natural and local materials as possible and respecting traditional ways of construction. Comfort, details, art and nature converge at this affordable hostel.

Address: Michel Perez street 1-3, Copacabana

Website: www.hostallasolas.com

Photo: Hostal Las Olas

---

ART/COSTUME RENTAL

ARTESANÍAS PALOMITA

Description: Founded in 1985 by Carmen Prieto de Clavijo, it’s the first costume rental store specialised in traditional clothes from the Potosi Department; it played a pioneering role in the recuperation of Chola Potosina traditional costume, which has become a landmark of Potosi. Opening hours: Monday to Friday 10:00 – 13:00 / 15:00 –18:30 Saturday 10:00 – 13:00

Address: Av. Serrudo #152, Potosí - Bolivia

Cell phone: +591 63708590

Facebook Page: @artesaniaspalomita

Photo: Artesanías Palomita

---

RESTAURANTS

LA CASA DE LES NINGUNES: JUEVES DE COMIDA CONSCIENTE

Description: Once a month La Casa de Les Ningunes opens their doors to share food and knowledge with the community. Under the principles of the conscious food movement and in collaboration with local gastronomic entrepreneurs, they create a delicious menu with tasty and healthy food, combining local and native ingredients to create a unique experience.

Address: Sopocachi, Rosendo Gutiérrez street, #696

Opening hours: 12:30-14:30

Photo: Movimiento Comida Consciente

---

COFFEE SHOP

HIGHER GROUND CAFE & WINE BAR LA PAZ

Description: A Melbourne-style cafe in the centre of La Paz, this place offers a selection of selected coffee, international teas, Bolivian beers, wines and spirits. The food is fresh and flavourful and you’ll find familiar dishes with a Bolivian twist.

Address: Tarija street #229

Opening hours: 6:30-22:00

Photo: Higher Ground Cafe & Wine Bar La Paz

---

SHOPPING

VAGABOND

Description: Vagabond, a Bolivian leather goods producing company born by the filosophy 'Be Free - Live Simply', allows you to experience the joy of every-day activities through simple pragmatic design of all the pieces that are thoughtfully handmade.

Address: San Miguel, Gabriel René Moreno and Ferrecio corner, #1307

Opening hours: 10:30 - 13:00 15:30 - 20:00

Website: www.vagabondbolivia.com

Photo: Vagabond Bolivia

Images: Courtesy of Antonio Jadue

The Palestinian diaspora in Bolivia

In 2018, to no small fanfare, the Bolivian government announced the official opening of the Palestinian Embassy in La Paz. The move was heralded by Bolivian President Evo Morales as signaling a new era in diplomatic relations between the two countries, paving the way for ever closer ties and mutual support. However, it also spoke to a far longer history of Palestinian presence in Bolvia which has resulted in upwards of 15,000 people of Palestinian descent living in the country today.

The history of the Palestinian community in Bolivia begins at the turn of the 20th century, at a time when Palestine was still under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire and ruled from Istanbul. Around that time, young Palestinian men began arriving in Latin America, travelling by boat to reach the great port cities along the continent’s Atlantic coast, especially in Argentina. These immigrants were usually the elder sons of Palestinian families, literate and well educated, sent off in search of economic opportunity and hoped-for prosperity.

Often whole clans would travel this way, with men accompanied by cousins from other branches of their extended family. For example, the al-Hadwahs, a notable family from Beit Jala, then a small farming village rich in olive groves and orange trees perched on the hillsides northwest of Bethlehem, sent six of their sons to seek their fortune in the New World.

Along the way, Arabic surnames became Hispanicised. Sabbagh changed to Sapag or Sabag, Salamah to Seleme or Salame. Hazboun, the surname of one of the largest and most notable families of Bethlehem, morphed into Asbún, under which name the family’s most famous son, Juan Pereda, would become President of Bolivia in 1978.

Sometimes immigrants would adopt completely new family names. David Mansour changed his name to Mendoza in honour of the Argentine city in which he first settled before he eventually moved to Vallegrande, Bolivia. His son Rafael would go on to become a noted entrepreneur most famous for founding the Bolivian Professional Football League and his time as president of The Strongest, one of the country’s most successful sides.

The six al-Hadwah sons, having arrived by steamer in Buenos Aires in the first half of the 20th century and adopting the name Jadue, then carried on east. Five went to Chile, where amongst their descendents are numerous notable figures, including Óscar Daniel Jadue, mayor of Recoleta, and Sergio Jadue, former president of the Chilean Football Association. However, the sixth cousin, Jhamil Jadue Saffadi, travelled on to Bolivia.

The majority of early Palestinian immigrants to Bolivia settled in the west of the country, along the Andes in cities such as La Paz, Oruro, Cochabamba and Potosí. This contrasted with immigrants from other parts of the Arab world, who tended to settle in the east of the country, working as miners or merchants. Jhamil Jadue settled in Vallegrande, in the western mountainous region of the Santa Cruz department.

There are upwards of 15,000 people of Palestinian descent living in Bolivia today.

Jhamil’s grandson, Antonio Jadue, recalled that in those days, with men arriving alone without close relatives, it was very hard to maintain the cultural traditions and practices of their homeland. ‘Keeping up their traditions was very hard since they arrived alone,’ he said. ‘They had to adapt to the Bolivian way of life.’ As such, it was very hard to preserve the Arabic language, the cooking of traditional food and other customs for early immigrants, and amongst the first generations of immigrants Palestinian identity became weaker and weaker. Antonio reflected that, ‘We lost two generations of Palestinians.’

Parents often did not make an effort to pass on their customs and language, and in this way the children born in Bolivia from Palestinian immigrants became isolated from their cultural heritage. This left what Antonio called a ‘great hole’, where men and women of Palestinian descent often would not even know of their roots, let alone communicate with their grandparents or greatparents in their mother tongue.

Antonio’s father, Jaime, one of seven sons, was therefore unusual in that he made a special effort to teach his sons about their backgrounds, believing that ‘once you lose your sense of identity you are nobody.’ As a child growing up in Sucre, Antonio learnt about the history and traditions of his grandfather's land, while his father also encouraged him to come together with others of Palestinian origin in cultural or sporting events, often organised through clubs which brought together those of Arab descent living in Bolivia. These experiences proved formative for the young man, instilling within him ‘a love for Palestine, for our land, our roots.’

Growing up, Antonio also became an indirect witness to momentous events taking place in the Holy Land on the other side of the globe. His father would often host immigrants who had recently come to Bolivia, providing them with advice in their new surroundings. He had a strong sense of duty, feeling that it was his responsibility to lend support to the newcomers. The stories of these new arrivals gave Antonio a glimpse into what it was like for those still living in Palestine.

These men and women left a very different Palestine than the homeland that Jhamil’s generation had left. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire, in 1918, dramatically changed the political landscape in the Middle East, with the British gaining control of Palestine. When, in 1947, the British announced their intention to withdraw, the country erupted into violence, as the Arab and Jewish communities competed to fill the political vacuum.

In the ensuing war, the new state of Israel, declared on 14 May 1948, roundly defeated the Palestinians and their backers in neighbouring Arab states, expanding beyond the borders allocated by a UN plan. In the process, over 750,000 Palestinians were either forced to flee or violently expelled from their homes by Israeli troops in what became known as al-Nakba, or ‘the Catastrophe.’ This created a wave of immigrants to Bolivia and other Latin American countries who arrived not as economic migrants but as refugees. In 1967, another decisive Israeli war victory led to the occupation of the remaining Palestinian lands in Gaza and the West Bank, which still continues today and has prompted another tide of refugees to flee the country.

Stories of al-Nakba made a deep impression on Antonio, despite not having experienced them first-hand. As a young man, Antonio became deeply dissatisfied with lack of awareness of the ongoing Israeli occupation and humanitarian crisis in Palestine. Though he belonged to the Bolivian-Arab Youth, an organisation that seeks to preserve and encourage Arab culture amongst the diaspora living in Bolivia, he came to realise that ‘meetings of young people in Bolivia wouldn’t help anybody,’ he said. ‘The meetings closed, and nothing more would happen.’ There was a need to assist those living under occupation.

As such, Antonio decided to found the Colectividad Palestina de Bolivia (CPB), which would not only represent the Palestinian diaspora in Bolivia but also play an active political role to improve the situation in Palestine itself. After consulting with similar groups in other Latin American countries, Antonio and his colleagues founded the CPB in 2000, at which point Antonio said ‘the Palestinian cause awakened in Bolivia.’

The Colectividad Palestina de Bolivia not only represents the Palestinian diaspora in Bolivia; it also plays an active political role to improve the situation in Palestine itself.

Since its creation, the CPB has focused on raising awareness of the situation in Palestine amongst ordinary people in Bolivia, working not only with the Arab community but within wider civil society, for example local church and faith groups, to educate and inform Bolivian society about the Palestinian cause.

However, it is on the international stage where the CPB’s development has been most impressive. As the organisation grew, it began to participate first in regional forums with similar bodies from around Latin America, and then in global pro-Palestine conferences. For example, as a representative of the CPB Antonio has travelled to conferences in Lebanon, Turkey and Morocco, amongst many other countries. He admitted that the work, especially the travel, can be draining, but he says that his overhwelming emotion is one of pride in being able to ‘raise the Palestinian flag high wherever I go.’

The CPB also played an important role in the opening of the Palestinian Embassy in La Paz in 2018. In 2017, at a meeting with Palestinian National Authority Foreign Affairs Minister Riyad Al-Malki in Chile, Antonio discussed the opening of an embassy in Bolivia, saying that it was ‘illogical that a country that provides such support for the Palestinian cause does not have an embassy,’ while the continued lobbying of the CPB was a key driving force as the plan gathered momentum.

The opening of the embassy highlights that it is not only the history of Palestinian immigration to Bolivia that binds the two countries together; they’re also bound politically, becoming closer allies. As Antonio notes, Evo Morales is ‘the first president to lend his unconditional support to the Palestinian cause,’ arguing the country’s case in the United Nations and signing numerous bilateral agreements. The latest of these was signed on 22 July, pledging closer cooperation on development issues and signalling that in Bolivia Palestinians have found not only a welcoming host country but a stalwart ally on the international stage.

Photos: Rhiannon Matthias

Empowerment and community

When one thinks of female empowerment, perhaps pole dancing is the last thing that springs to mind. Pole dancing (the preferred term by practitioners is pole sports, or poling) has long been seen as playing into the hands of misogyny, a symbol of exploitation and hypersexualisation. Yet at the Turmalina Pole Sport y Movimiento studio, there’s an atmosphere of community and positivity. As strong women and men fight against gravity in between the spins, inversions and holds, there’s laughter and high fives.

Turmalina opened its doors in 2012 as the first pole school in La Paz. Cecilia Ardaya, its founder, is a biochemist and dancer originally from Cochabamba. She took up poling 10 years ago and fell in love with it after her first class, saying that it allowed her to reconnect with her body. With two master’s degrees under her belt, the one thing that was missing was a space to practice pole.

Initially, the studio was located in Miraflores, with a small student base mostly made up of people with dance backgrounds. After relocating it to the centre, Ardaya rechristened the studio Turmalina. Classes are taught in a light and modern space with eclectic decorations ranging from Tibetan prayer flags, unicorn stickers and a wall covered in certifications and awards. Now the majority of dancers are students and professionals, who work or study full-time and attend classes in the evening, trading in their work clothes for hot pants and knee pads.

As one student explains, the studio provides a respite from the city and allows practitioners to move their deskbound and stagnant bodies in innovative ways. Valentina, a student who has been practising for four years, explains how pole sports has provided her with an arena in which the anxieties and stress of the outside world disappear; she is able to concentrate and focus in a space where she can be her most authentic self.

‘People have this idea that the pole is something women take up in order to impress their husbands,’ Ardaya says. ‘Of course, some people may have those intentions, and that’s fine. Pole is an art form, and it forces you to concentrate and focus, because if you don’t you can seriously hurt yourself.’

A Turmalina instructor says that the students shed layers in during the pole classes – both their clothing and their emotions – and see themselves in a completely new light. There are three pole styles: artistic, fitness/sport and exotic. Exotic pole is more sensual, involving floor work, flexibility and the so-called ‘stripper heels.’ It’s a great way for a woman to explore her body and femininity. ‘Even the provocative moves that are sometimes part of pole routines shouldn’t be seen in a negative light,’ the instructor says. ‘It boosts your self-esteem and teaches you to accept your body.’

As one of the first polers in La Paz, Ardaya has faced some undesirable reactions, ranging from men asking her ‘How much for a dance?’ to judgement from other women. The stigma against pole artists is misplaced, to say the least, as pole fitness is a discipline which has been reappropriated and largely defined by women who perform it for their own benefit. Male pole artists face a different kind of prejudice. They comprise just a small part of the community, but few of them are open about their pastime. This judgement stems the pole’s association with strip clubs, where women perform for the pleasure and entertainment of (mostly) men. But as Ardaya explains, pole-based movements can be traced back to ancient India, where yogis practised yoga postures on thick wooden poles known as mallakhambs.

‘Pole is an art form, and it forces you to concentrate and focus, because if you don’t you can seriously hurt yourself.’

—Turmalina’s Cecilia Ardaya

Pole requires a tremendous amount of strength. Each move – of which there are over 100 – entails a great deal of pain and determination, as dancers use skin-to-pole contact and muscular tenacity to fight against gravity. Pole artists require much upper-body strength, which requires commitment and patience. Many Turmalin@s (as they call themselves) also practice gruelling conditioning and stretching exercises daily. ‘In pole you do things that you could have never even imagined; each class is a challenge,’ Ardaya says. ‘As you complete these mini-challenges in pole it spills over into other areas of your life, and helps you gain self-esteem. I notice the changes in people who start out being visibly shy and unsure of themselves, but with time you see them come out of their shell. Their postures change, you see the confidence reflected throughout their body and in their demeanour.’

Although there’s still some scepticism as to the validity of poling as an art form and sport, its potential to strengthen and empower is reflected in its popularity. Thanks to the boldness and determination of women like Ardaya, poling has become a bona fide fitness trend around the world. The Turmalina team has produced many instructors – both male and female – some of whom have gone on to open up their own schools in other parts of the city. In fact, there are now three other pole schools in the city, one of which was opened by a former Turmalin@. The future of pole looks bright and the community continues to grow with over 11 official schools throughout Bolivia.

Studios like Turmalina provide a safe space for women and men of all ages, body types, fitness levels and gender identities. While there, students are able to come out of the shells that society imposes on them. Women can exhibit sexiness and strength without fearing the ridicule, disrespect, harassment or violence so common in the outside world. People of all gender identities and sexual orientations are given a welcoming space in which they can be their authentic selves, without facing judgement for being ‘too feminine’ or ‘too masculine.’

The security of this space is particularly important in patriarchal and conservative society where women face excessive machismo. Violence towards women is a pressing issue in Bolivia, and advertising and media further solidify negative stereotypes about women and femininity. ‘When people say that pole is misogynistic, I often feel that there are other things that are widely socially accepted and far more harmful to women, like advertisements or the pressure to get married,’ Mel, a Turmalin@, says.

The pole community helps women build healthy relationships with their own bodies and sexuality. Studios like Turmalina boost women’s pride in themselves. But poling isn’t just about building strength or self-esteem; it’s about practitioners supporting and teaching one another, lifting each other up – sometimes quite literally – and being taught how to lift up oneself too.

Download

Download