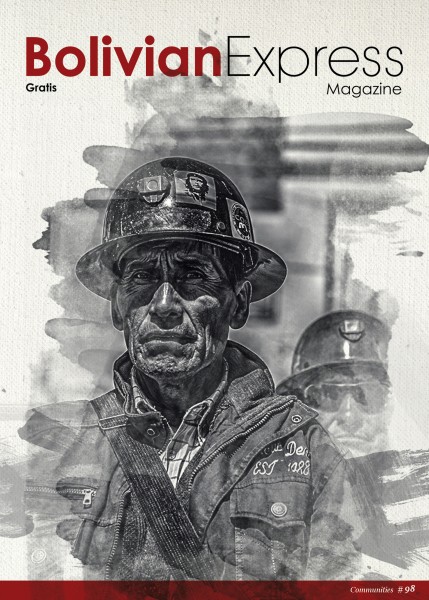

Cover: Jaime Cuellar Imaña @jcuellar18

COMMUNITIES

The Amazon fires destroyed over 4.2 million acres (1.7 million hectares) of Bolivian rainforest since 15 August. This number doesn’t take into account the fires in Brazil and Paraguay and what is still burning today. Man-made catastrophes such as these make us reflect on ourselves, on our individual lifestyle choices and on how we stand as a species. But ultimately, it makes us react as a whole, as a community; it reminds us that we are all connected and that this connection can be felt from across continents.

This issue focuses on communities, groups of people bound by common attitudes, interests, and goals: family, neighbours, friends, members of a political party, vegans and more. Our community helps us survive and gives us a sense of belonging and identity, but the nation-state is in decline, religions are losing their appeal and, filling that void, new global communities have arisen: digital worlds, chosen ideologies, foreign cultures.

To illustrate this, in the most remote corners of the Bolivian countryside one can find images of Korean pop stars on the notebooks of children who can reproduce choreographies and sing along to Korean pop songs. This may be a symptom of Bolivia suffering from the same disenchantment with authority figures as the rest of the world, but it mostly means that Bolivia is very much a part of the global community.

Veganism is another trend that has reached Bolivia. Perhaps veganism is more than a simple fad, as it operates as a secular religion by promoting a way of life and philosophy. The popularity of plant-based food in La Paz is not just a phase; the movement – and similar conscious-food initiatives – was able to establish itself because of how well it fits in with the local understanding of the world. We may be witnessing a new type of syncretism taking place in which the local and the global intertwine to create something new.

If Bolivia is part of a global community, family remains the chore of the Bolivian identity. The family unit is what defines and forges us. But it doesn’t have to be the only community we belong to. Now one’s community is not just immediate family and neighbours; our community is where we want it to be with the people we choose to be around.

Images: Courtesy of Casa Real

The traditional bolivian liqueur is increasingly recognized on the world stage

Singani is a grape-based liqueur produced in a few selected Bolivian high valleys. It was declared a ‘Domain of Origin’ by the Bolivian government in 1992 and is considered a part of the country’s cultural patrimony. Less internationally known than grappa, brandy or pisco, it stands on its own merits despite still being classified as a brandy for international trade purposes.

The origins of the drink can be traced to the 16th century somewhere in the south of the Potosí department. The Spaniards found that the wine they were used to drinking wasn’t suited to area conditions – because of the altitude and rainy season affecting the making and conservation of wine – and that they needed a stronger beverage that was more resistant to the extreme climate conditions. It is believed that the name singani originated from the place it was first produced, although it could also refer to the Aymara word siwingani, for sedge.

Singani rapidly gained popularity throughout the Bolivian territory. This was helped by the success of the chuflay drink, which still remains a Bolivian favourite in bars and house parties alike. The cocktail appeared in the 18th century when English rail workers who were craving ginger ale and gin replaced the gin with singani. Because it felt like a shortcut, they named the drink ‘short fly’, railway jargon meaning precisely that, which became ‘chuflay’ when pronounced by the local population.

Singani’s production process involves several distillations and the addition of water in some cases to obtain varying levels of quality. Singani de altura/gran singani is made from a distillation of a base wine. Singani de primera and singani de segunda is made from grape marc, a byproduct of winemaking. All singani is then aged between six months and one year in French oak or copper barrels, and the finished product has an alcoholic content of 40 percent.

Singani is closer to grappa in its fabrication and, despite their geographical proximity, differs with pisco in significant ways. Except for the fact that they are both made from grapes, there is little in common between the two. Pisco has a slightly higher alcohol content (between 42 and 48 percent); it can be made from eight grape varieties that are blended in various combinations; and only one distillation is required.

Nowadays, singani is produced in the valleys south of Potosí and near Tarija. The high elevation (muscatel grapes are only grown in Bolivia at an altitude greater than 1,600 metres above sea level) and traditional method of fabrication, which is still very similar to the original one, give the liqueur a very fruity, complex and intense flavour. Singani is certainly not a ‘Bolivian pisco’; it has a very unique and distinctive taste that deserves its own international classification and appreciation in the world market.

Illustrations: Alejandro Archondo Vidaurre

Experiencing an alternative, communal way of life

The recent ecological crisis brings feelings of anguish and uncertainty, leaving us to wonder if anyone can we fix this disaster – governments, industries, society? But these options don’t quite fit the reality we live in. It’s our daily bad habits that are responsible, in part, for the environmental crisis that is affecting us. We cannot change everything at once, but we can change some things little by little. There is a current trend called mindfoodness, or conscious food, which is a way we can change our bad habits and improve our way of life.

The Casa de Les Ningunes, based in Sopocachi, La Paz, is a clear example of how a small community is trying to make an impact on everyday attitudes in relation to the environment. The Ningunes’ project was initiated by a group of environmentalists who wanted to put into practice ideas of how to live more consciously, not only in regard to environmental issues, but also in an economical and cooperative way of life.

The Ningunes’ name is inspired by a poem by Eduardo Galeano called ‘Los Nadies.’ The poem refers to the society’s outcasts, the Nobodies. ‘Over time I have understood that the name holds a lot of the essence of the house and the project because it is not just someone's project,’ Nina Villanueva, a member of Les Ningunes, explains. ‘It is not in someone's name or has acronyms or has a surname – the house is really for everyone and nobody.’

The philosophy behind this community goes beyond just asking for the ban of plastic straws in coffee shops; they live by principles and structures that they constantly work to improve and redefine. The contribution of Les Ningunes aims to be part of a cultural revolution in eating habits and food consumption. Gabriela Sáenz, also a member of Les Ningunes, says that everyone coexisting in the house has a role. They may live together and share a space, but their coexistence is based on respect and agreements: ‘When it comes to food, we divide the tasks to cook and wash, and everything is for everyone,’ Saenz says. ‘Cooking and eating conscious food is one of the main principles that the house follows.’ Ningunes members also organise activities such as workshops, talks, meetings and assemblies that allow them to manage their internal micropolitics in order to improve their work together and coexist harmoniously.

The house works according to roles, principles and agreements, helping members organise themselves but also allowing them to have their own space. The group’s structure is based on the Tamera community in Portugal and the Transition Network in England. ‘This house groups people of different ages, backgrounds, nationalities, sexual and life orientations; we are not a sect with a guru, but we are a community with an intentional relationship,’ says Villanueva. ‘It often feels like a family, but it is not. If we like each other, it’s because we want to. Nobody is here because they have to, but because they choose this coexistence. We decided to work and live together.’

Another central tenet of the collective is to be self-sufficiency. The house has a garden in which organic products are grown, and which is watered by a rainwater irrigation system. All the garbage is separated, composted and recycled. This lifestyle involves hard and constant work and sustains itself by activities such as catering services, conscious Thursday lunches and the rental of its spaces for meetings and/or workshops. ‘Les Ningunes wants to be self-sustaining, but that has always been as part of the challenge – to find a balance between expenses and activities,’ Sáenz says.

Les Ningunes have been contributing significantly to the growing conscious-food trend in La Paz, where many restaurants, cafés and private chefs have joined the movement by cooking delicious, nutritious and environmentally friendly dishes.

Photos: Amelia Swaby

Bolivia goes back to its roots

As the recent fires in the Amazon make clear, we need to drastically reduce our red-meat consumption to combat the climate crisis. Our food choices have a direct, far-reaching impact; one of the key causes of the fires is the ‘slash-and-burn’ deforestation techniques used by cattle ranchers. But by reducing our red-meat intake, and generally being more ethical consumers, we can drastically reduce our global impact. Veganism, a lifestyle in which one does not use or eat any animal products, is one route towards this.

The Economist called 2019 ‘the year of the vegan,’ in which more people embraced the plant-based lifestyle. A 2016 Nielsen survey on food preferences discovered that vegetarians made up eight percent and vegans four percent of the population across Latin America. But what about Bolivia?

Bolivia is rich in natural products and cultivates an immense number of traditional grains (including quinoa, amaranth and cañahua) as well as boasting a large variety of beans and seeds.

From vegan fast food to café culture and fine dining, there is a growing number of vegan options in Bolivia to suit any preference and budget. For commercial (as well as ethical) reasons, more restaurants are now offering vegan dishes too; they don’t want to miss out on business. Even the supermarkets seem to be catching on and offering more vegan food alternatives, such as plant-based milk substitutes and tofu.

With an ever-increasing number of vegetarians and vegans in Bolivia, La Paz is a haven for vegan eats. Here are a few of the options for eating in and dining out. With so many on offer, which will you try?

---

The Fine-Diner: Ali Pacha

Ali Pacha, which means ‘universe of plants’ in Aymara, offers a gourmet experience with its lunch and dinner tasting menus.

Sebastian Quiroga, the restaurant’s owner, founder and executive chef, studied French cuisine and patisserie in London. But it was in Copenhagen where he ‘saw the vegetable as the star of the dish itself rather than the meat.’ After turning vegan, moving back to La Paz and still working in the fine-dining industry, Quiroga decided to open his own fully vegan fine-dining establishment.

Deciding to open in the central business district of La Paz, far away from Zona Sur, where the newer trendy restaurants are normally located, Quiroga wanted to help revitalise the old neighbourhood. Ali Pacha is located in a restored house, decorated with recycled wood, furniture and even flour sacks for the soft furnishings. For Quiroga, sustainability is not just about food.

The offerings at Ali Pacha depend on what’s fresh and available. ‘We don’t reveal the menu until it is on the table,’ Quiroga says. ‘So every single dish is explained by the chefs, as well as the pairings of the wines for each course.’

Quiroga says that Ali Pacha’s blind tasting menu was designed because Bolivian people – famously preferring a meat-heavy diet – might be turned off by a menu featuring only vegetables. At the beginning, many customers came purely out of curiosity. The offerings change seasonally, making the most of Bolivian products in their prime, which Quiroga is extremely proud of and wants to showcase in new and creative ways.

Quiroga says that the message behind the food at Ali Pacha is to show Bolivians ‘how to be proud of our country and present the plant-based and vegan mindset as more digestible for a carnivore,’ to show ‘what Bolivian cuisine has to offer and how versatile it is.’ He wants to showcase the food to Bolivian people, open their minds and help them get ‘to know [their] city in a different way.’ He wants his customers to take away the memories of traditional fava beans or quinoa cooked in a completely different way.

‘Our ingredients represent Bolivia in general,’ Quiroga says. ‘Peanuts and peppers were actually discovered in Sucre and brought into the world. We are really proud to be using these plant-based products that are fully Bolivian.’

‘La Paz is opening and starting to bloom; there are so many possibilities here,’ Quiroga says. ‘I think [vegan cuisine] is just going to keep growing.’

---

The Bolivian Favorite: Lupito Cocina Vegana

Heart-warmingly named after a rescue dog close to owner Luisa Fernanda España Peñaranda’s heart, Lupito is more than just a restaurant; it is a community project founded on the principles of ‘ethics, love and respect for all species.’

España says that Lupita focuses on ‘returning to the Bolivian ancestral customs, such as an abundance of long-forgotten grains’ to educate customers on the benefits that different foods possess and how they can live more consciously. Lupita’s relaxed setting encourages guests to ask questions and investigate the benefits of Bolivia’s natural products.

España and head chef Heydi Chávez fight the preconception that vegan food is expensive by providing a wide range of it which is both nutritious and exciting, making the most of local products found in the market. Each dish they create shows customers that vegan food doesn’t equal restriction.

The staff at Lupito is committed to serving customers up nutritious dishes that they will love and which will excite them. Each plate is a demonstration of the possibilities of vegan cuisine, all with a hint of Andean flavours and ‘creativity and passion at the heart of each creation.’

Lupito focuses on forging relationships with its customers, who are viewed more like friends. Some older customers and families now even have pensions set up with the restaurant, and they eat there daily at a discount.

España believes there is an increasing collective conscience in returning to past Bolivian cuisine, which is more plant-based, rich in grains and locally sourced than most contemporary foods, for health, environmental or animal-welfare reasons.

In the future, España is looking to grow and improve Lupita on all fronts and continue educating Bolivians on the benefits of Bolivia’s plant-based cuisine. ‘La Paz is on a positive path,’ she says. ‘We have planted the seed and are waiting for the impact to flourish.’

---

Quick and Easy: Flor de Loto

This vegetarian and vegan buffet allows diners to explore the variety and freedom of plant-based eating in a very relaxed setting; customers can eat what they want, as much as they want and in any order.

The large selection of hot food changes daily, so customers are always offered something new and exciting to try. Owner Mariana Terán wants to change the mindset that vegetarian and vegan food is boring and lacking nutrients. So, using locally sourced organic ingredients, Terán offers customers a variety of global cuisines, from Asia to Bolivia and everywhere in between.

The restaurant is attached to the La Huerta grocery store, where after enjoying their meal customers can shop and ‘take the mindset home with them,’ as Terán says.

---

The Café Culture Addict: Café Vida

Ninneth Geraldinne Echeverría León started out as just a worker at Café Vida, but in 2016, at only 21 years of age, she took over the business from her mentor, María Borda Kantuta. Initially, Echeverría was reluctant to change anything about the café at all. However, little by little, Café Vida has grown, flourished and expanded – with more plans to expand in the near future – into the haven it is today.

For Echeverría, Café Vida represents ‘an alternative place to eat,’ where everyone can share and enjoy and feel at home and make themselves comfortable. This couldn’t be more true given the sofa bed at the back of the café surrounded by fairy lights; it’s the perfect setting to relax after a nutritious lunch.

The café offers a variety of different plates, from smoothie bowls and snacks to burgers and creative sandwiches, all which aim to achieve nutritional balance. The most popular dish, according to Echeverría, is currently the Inca bowl, but she shared that her personal favourite is the vegan burrito.

Echeverría says that La Paz has witnessed an increased level of consciousness about the danger and impact of its current meat-heavy diet, from the number of people interested in learning about a vegan diet and the number of new vegan restaurants opening. More people are open to trying plant-based food, she says. She adds that the younger generation seems to be more driven by ethics regarding environmental and animal welfare, and the older generation is more concerned for health reasons.

Whatever their motive, many are turning to a plant-based diet, moving away from the pollo frito available on many street corners and once again incorporating more of Bolivia’s natural plant products such as yuca, vegetables, corn, quinoa and potatoes. Echeverría says that vegan food is delicious because each element of a dish has its own distinct taste and isn’t simply overpowered by meat. ‘There is a whole world of food to explore: spices, different combinations,’ she says. ‘You just have to be creative and practice.’

---

The Vegan Junkie: Aguacate

After hearing that the seitan at Aguacate was proclaimed by locals as the best in La Paz, my expectations were high as I travelled to the San Miguel neighbourhood in Zona Sur.

Originally founded in 2016 as a project advocating ethical eating and sustainability, Aguacate became a vegan haven in March 2019. Head chef Carla Rodriguez and owner Lucía Aliaga want to show what can be vegan, taking meaty favourites and things they liked to eat at home and ‘veganifiying them.’

This is where the taste and texture of the seitan comes to light; Aguacate’s meaty skewers, nuggets and sandwiches could fool even the most carnivorous customers.

Awareness of what ‘vegan’ actually means and that ‘it is not just a diet, but a lifestyle,’ as Aliaga says, has increased significantly in the last five years. Whilst delivering a nutritious twist on ‘vegan junk food’, Rodriguez and Aliaga take advantage of the numerous aspects of local and natural Bolivian products, one example being the yuca cheese on Aguacate’s pizzas which, like the majority of the food and drink here, is made in house from scratch. I’m usually wary of vegan cheese, but I think that its taste and texture (including its melting ability) were amazing.

Rodriguez and Aliaga are challenging the fixed ‘meat mindset, taking advantage of the opening which has recently exploded worldwide’, and promoting a vegan diet and more ethical lifestyle. ‘We want Bolivia to follow a different path, away from industrialised meat production,’ Aliaga says. The concept of sustainability is very important for Rodriguez and Aliaga, and Aguacate has no plastic on site and customers are encouraged to bring their own reusable takeout containers.

‘As Latinos, we can see the impacts of the [meat] industry,’ Aliaga says. ‘The destruction of the Amazon is geographically so close to us. We have a lot – we need to value it and find new ways of developing which allow us to maintain it.’

---

For the Home Cook: Tierra Viva

Paola Cespedes Inclan opened Tierra Viva, on Calle Victor Sanjinez near Plaza España in La Paz’s Sopocachi neighbourhood, to offer more vegan and vegetarian products to meet the ever-growing demand. She combined forces with a friend who wanted to offer products without gluten, meaning the shop offers healthy, low-sugar and natural products which are all vegetarian or vegan and gluten-free.

In the last two years, Cespedes has noticed a big increase in the number of vegans in La Paz, and people who are curious about the vegan lifestyle and come to her for nutritional advice. However, supermarkets do not carry many vegan or natural products, and what they do sell is usually expensive. Cespedes and Tierra Viva are countering this with accessible and locally sourced products.

‘There is an increasing level of consciousness regarding the planet, when it comes to many aspects of life, not just food,’ Cespedes says. ‘The youth, above all, they are leading the way.’ Additionally, she says there is ‘an increasing desire to reclaim the cultural customs of the country, to turn back to our local foods of each region, to turn back to the food of our past.’

Download

Download