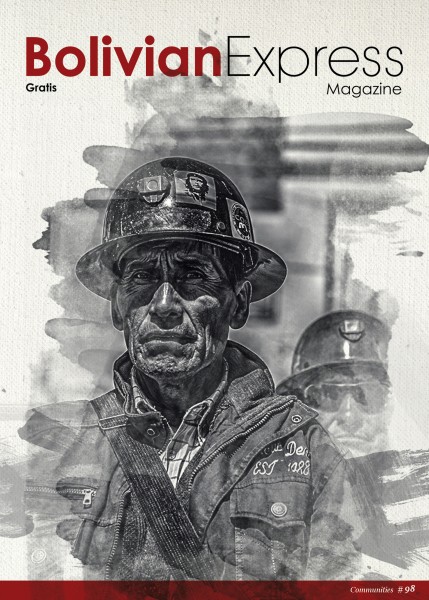

Cover: Jaime Cuellar Imaña @jcuellar18

COMMUNITIES

The Amazon fires destroyed over 4.2 million acres (1.7 million hectares) of Bolivian rainforest since 15 August. This number doesn’t take into account the fires in Brazil and Paraguay and what is still burning today. Man-made catastrophes such as these make us reflect on ourselves, on our individual lifestyle choices and on how we stand as a species. But ultimately, it makes us react as a whole, as a community; it reminds us that we are all connected and that this connection can be felt from across continents.

This issue focuses on communities, groups of people bound by common attitudes, interests, and goals: family, neighbours, friends, members of a political party, vegans and more. Our community helps us survive and gives us a sense of belonging and identity, but the nation-state is in decline, religions are losing their appeal and, filling that void, new global communities have arisen: digital worlds, chosen ideologies, foreign cultures.

To illustrate this, in the most remote corners of the Bolivian countryside one can find images of Korean pop stars on the notebooks of children who can reproduce choreographies and sing along to Korean pop songs. This may be a symptom of Bolivia suffering from the same disenchantment with authority figures as the rest of the world, but it mostly means that Bolivia is very much a part of the global community.

Veganism is another trend that has reached Bolivia. Perhaps veganism is more than a simple fad, as it operates as a secular religion by promoting a way of life and philosophy. The popularity of plant-based food in La Paz is not just a phase; the movement – and similar conscious-food initiatives – was able to establish itself because of how well it fits in with the local understanding of the world. We may be witnessing a new type of syncretism taking place in which the local and the global intertwine to create something new.

If Bolivia is part of a global community, family remains the chore of the Bolivian identity. The family unit is what defines and forges us. But it doesn’t have to be the only community we belong to. Now one’s community is not just immediate family and neighbours; our community is where we want it to be with the people we choose to be around.

Photos: Sergio Suárez

The UK’s flagship scholarship for future leaders

The UK government’s Chevening international awards programme aims to develop global leaders. The scholarship is fully funded, covering flights, accommodation and course fees, allowing recipients to live in the United Kingdom for a year while pursuing a master’s degree at a prestigious university. The BX team talked with the United Kingdom’s ambassador to Bolivia, Jeff Glekin, and also reached out to past and current Cheveners to talk about their experiences and expectations.

According to Glekin, ‘The goal of the scholarship is to identify and nurture future leaders, to help strengthen the relationship between the UK and Bolivia and to create a network of scholars both in Bolivia and around the world who can support one another in their goals.’

The programme started in Bolivia in 1998 and has benefited 148 scholars so far. It is open to any citizen of an eligible country, who must commit to returning to their country of citizenship for a minimum of two years after the award has ended, thus contributing to that country’s future growth and development. For Glekin, leadership comes in all shapes and forms and can be found anywhere in Bolivia. The administrators of the Chevening programme are not looking for people with any specific backgrounds; instead, they look for people who have shown real leadership potential, encouraging applicants from as diverse backgrounds as possible.

This year the UK Embassy is launching a mentoring programme to assist applicants to the Chevening programme. ‘Those who are most successful are people who can articulate most clearly what they want to achieve for themselves and for their country, and those are the people who can make an impact on the long term,’ Glekin said.

---

Vania Rodriguez Saavedra

28

Fashion Designer

MSc Applied Psychology in Fashion

University of the Arts London

London

2019–20

‘I’m really excited to have won the scholarship because I’m the first person in a creative field that received the scholarship in Bolivia…. I found one master’s programme that was ideal for me because I’m starting to reshape the way the fashion industry is working in Bolivia, and the master’s aims directly at that. I think this is going to help me grow in my area of expertise,’ Rodriguez said.

She also had some advice for applicants: ‘For the creative people who want to apply, consider that they have to be leaders in their industry. They also need to prove how their particular expertise can help the development of the nation; it actually has to help the economy in some way.’

---

Jose Manuel Rioja Ortega

30

Industrial Engineer

MSc Investment, Banking & Finance

University of Glasgow

Glasgow

2019–20

‘I would really like to bring back financial technology [to Bolivia],’ Rioja said. ‘And I think it will be a great experience with a lot of competition. Because it is the people who surround you that make you, so I think that if you compete with people performing at a higher level you will also be able to perform that way.’

‘Your own definition of success is going to help you a lot if you are applying to the scholarship or to any job,’ he added. ‘I follow [revered US NCAA basketball coach] John Wooden’s success definition that goes like this: “Success is peace of mind, which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you did your best to become the best you are capable of becoming.” That’s what success is for me, and this is how you are going to be happy, because you don’t measure yourself only by money or by assets, but by true happiness.’

---

Karina Breyzka Guzmán Miranda

35

Commercial Engineer

MSc International Public Policy

Queen Mary University of London

London

2017–18

‘I learned quite a lot from theatre plays,’ Guzmán said. ‘They give you a taste of culture on a deeper level. In general I really liked London because people help each other, you see many examples of kindness from random people. The experience also expanded completely how I understand things and my priorities as well because sometimes we take for granted some amazing things that we enjoy at home.’

Guzmán had some advice for people interested in the programme: ‘Don’t be afraid to apply, you have to be stubborn and persistent, and don’t let it go, just hold on tight until you finish the process and do the best you can. Be concise on what you want to do. It took me almost a whole year to prepare my application, not because it is difficult but because of the bureaucracy involved.’

‘We need to get this wonderful opportunity to everybody, to everyone in the country, because we have a lot of talent,’ she added. ‘We just need to be able to expand it, and a mission as Cheveners is to try to spread the word to everybody.’

---

Paola Andrea Escobari Vargas

31

Electronic Engineer

MSc Radio Frequency and Microwave Engineering

University of Surrey

Guildford

2016–17

‘In the last few years, India’s growth in the aerospace sector has been massive, and when I was interviewed for the Chevening I said that here in Bolivia we have the same opportunities as India because we have the human resources to make it,’ Escobari said. ‘The only thing that we need to do is to train people outside [of Bolivia] to become professionals so they can come back to the country to do it.’

---

Edwin Salcedo Aliaga

26

Systems Engineer

MScEng Advanced Software Engineering

University of Sheffield

Sheffield

2017–18

‘I really enjoyed participating in hackathons, which are 24-hour or 48-hour-long competitions where you have to develop a prototype of your idea,’ Salcedo said. ‘I participated in four or five events outside of [Sheffield], and it was really nice to participate because I met people from different backgrounds.’

---

This year’s application deadline for the Chevening programme is 5 November. Glekin recommends that applicants spend time thinking about why they might want to apply, what areas they may have to improve in, whether it’s the English language or preparing their example of leadership, so that when they do apply they have a clear and articulate application that really stands out.

Learn more at chevening.org

Photos: Amelia Swaby

The men behind the masks

Los lustrabotas, or lustras, are a familiar sight around La Paz, offering all passers-by a shoeshine and polish, trainers and sandals included. You will find lustrabotas in every plaza and street corner of the city, but these workers, often young men, are both visible and invisible at the same time. I was swiftly corrected by one gentleman I spoke with: lustrabota is a derogatory term; the correct, dignified name is lustracalzado.

Many lustras, especially the younger ones, wear balaclavas and baseball caps to hide their identities; apart from protection from the city’s cold and the chemicals they work with, lustras wear them to avoid the social stigma and discrimination attached to their profession. Many want to remain anonymous while they work hard to support their families or pay for their studies.

But I wanted to know what the lustrabotas thought. I wanted to hear the unique history behind each pasamontaña. As expected, I was turned away by lots of lustras who didn’t want to talk, but there were many who, when they started talking, wouldn’t stop. This cemented the fact there is a huge difference between lustras and the negative stereotypes they face.

---

Ramirón, 31 years old

Ramirón has been working as a lustra for more than 22 years, with other jobs on the side. ‘I earn very little,’ he said, ‘only [enough] to keep me going, but it isn’t enough to survive off.’

‘The mask is for different things,’ he added. ‘One is so that people don’t recognise you, as many of us hide [being a lustra] from our families… It is because of the discrimination… If my girlfriend knew I was a lustra, she would never accept me.’

---

Ilder, 25 years old

As I interviewed Ilder, he polished the shoes of five customers. Some of them made small talk, but most kept silent, not even asking for the service but simply placing their feet on the shoeshine box, headphones plugged in, staring down at the man squatting uncomfortably below.

One of the customers stated that lustras were very common in La Paz, just another part of life. One customer, smartly dressed in a business suit, added that he gets his shoes shined an average of three times a week at a minimum of two bolivianos a polish.

Ilder seemed happy with his business, offering that he earns ‘a lot – daily I earn 150 bolivianos,’ the equivalent of £17.90/US$20. Originally from the countryside, Ilder moved to La Paz for work. He now lives in El Alto and often travels to the city centre where business is more steady.

He firmly stated that he hadn’t experienced any kind of discrimination and that he wears his mask only to protect himself from the fumes of the shoe polish.

---

Ramiro and Reni

Ramiro was one of the few lustras I spoke to who wasn’t wearing a mask. This said, as soon as I pulled out my camera, a scarf appeared and he quickly covered his face.

We were joined halfway through the interview by his friend Reni, who threw fuel onto the fire. The pair were adamant, venomous even, that lustras who cover their faces are all robbers by night and gave other lustras a bad name. They even suggested that the younger hooded lustras frequently carry knives and hold up shop owners just for sweets. This was obviously a huge generalisation, but it’s easy to see how ingrained the discrimination against lustras is, even from those who are in the profession themselves.

Nevertheless, Ramiro said that discrimination should not exist, saying that ‘at the end of the day I dedicate myself to this job to survive.’

Both Ramiro and Reni said that these supposed crimes committed by lustras are fuelled by poverty. To which Reni added: ‘The police don’t do anything. There are no police around. There is no justice in Bolivia. They think we are all very poor, but we are not. We are not all the same. We are not all robbers.’

Reni ended with the remark that ‘people should work honestly and not rob. If they do, why do they need to wear a mask?’

---

Ignacio, Plaza Murillo

The discrimination against lustras was also evident when speaking with Ignacio, an older man who believed he was an original in the trade. Having not moved from his established spot with a permanent shoe shine chair for over 21 years, he now blames the ‘hooded, mobile lustras’ for stealing his business. He believed that these masked men give the trade a bad reputation, although people still hired them.

He said he had not had a customer for three days and that he often sleeps in his shoe shine chair, as there is no money, no jobs and nobody to help him.

---

Nico

A lack of work drove Nico to this lifestyle. For him, the mask is just for protection against the cold, sun and noxious fumes from the shoe polish. ‘Lots of people don’t understand, they think that wearing a mask is something bad.’

‘A lot of people discriminate against us, as they judge us on how we look… They look down on us, they devalue our jobs…but we are all equals.’

Nico accounted for the discrimination he and other lustras face to a ‘lack of education, discipline and respect.’

He furthered his bleak outlook on humanity by stating that ‘people will do anything to eat, to survive, they don’t feel anything.’

His hopes for the future? It seemed there were very few.

‘This discrimination won’t change in the future,’ he said. ‘I always say, the whole world, humanity, the planet is not ours, it is the gods. Everything is in the hands of the gods. Only the gods can change anything.’

He continued: ‘Nothing will change. People cannot change. No one can change a country. No one. Only the gods, they know everything.’

I asked what the government could do to fight the discrimination he faced. ‘Nothing,’ he quickly responded. ‘The people can’t do anything.’

---

Juan, 35 years old

Juan started working as a lustra at age 15. Now, 20 years later, he described how the lack of work in Bolivia meant he had to continue in this profession in order to provide for his family.

For him, the mask and hat are simply protection against the elements and chemicals in the polish. But he too has encountered discrimination. ‘People think we are bad boys, from the street, robbers,’ he said. ‘We are not.’

It appeared that Juan had a loyal clientele. He chatted and laughed with them jovially as he worked. This was a very different feel to the majority of lustras I had spent time with.

Despite his cheerfulness and warmth, Juan’s tone quickly saddened on the mention of his sons. ‘I want my sons to do better than me,’ he said. ‘I do this so they don’t have to.’

---

Ramon, 20 years old

The eldest of four brothers, Ramon said, ‘I work to provide food for my family and my studies. Life is tough.’

Despite his resentment at being a Lustra, Ramon said he hadn’t experienced any discrimination and that the mask, once again, was for protection from the fumes from the polish. He didn’t want to have his photo taken.

---

Ronan, 16 years old

‘My family knows what I do, but my friends don’t,’ Ronan said. ‘That’s why I wear the mask.’

Ronan saw working as a lustra only as short-term occupation, saying, ‘I use the money to pay for my studies, and for football. My dream is to be a footballer.’

There are organisations in La Paz actively fighting against the discrimination that marginalises lustras, such as El Hormigón Armado, a local newspaper which highlights the struggles that lustras face and provides career opportunities and educational funding for them.

For more information about the lustrabotas of La Paz, visit El Hormigón Armado

Photos: Amelia Swaby and Lola Newell

La Paz’s venerable ground-transport system modernises, but at a cost

Back in August, the inauguration of a new PumaKatari bus line connecting the southern neighbourhood of Huayllani to the centre of the city sparked a violent confrontation between the users of the new buses and the owner-operators of the familiar passenger minivans that comprise the bulk of the city’s traditional mass-transit system.

Protesters blocked streets, burned tyres and even threw rocks at the new buses. Social media was flooded with angry messages condemning the actions of the protestors. With the launch of the ChikiTiti system (which means ‘Andean cats’ in Aymara) – a smaller and faster line of buses integrated with the larger PumaKatari buses – and the growing discontent users are experiencing with the old-fashioned minivans, it seems unlikely that tensions will be resolved any time soon.

The city’s old minivans, micros and trufis are competing with the municipal buses and the state-owned teleférico system. Syndicates have a monopoly over the best routes and can mobilise strikes and blockades very quickly and efficiently. Each driver usually owns their own vehicle, and it’s not simply a job that they can quit and walk away from, finding employment elsewhere; it’s a way of life that they fiercely defend.

The recent violence is certainly not warranted, but in situations such as this, when each group antagonises the other, it may be important to remember that as public-transport users, inhabitants of La Paz and human beings, we should try to empathise with one another and think of transit and economic solutions so that we can live together in harmony.

Download

Download