PATRIMONY

In 1972, UNESCO adopted the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Bolivia signed the convention, but was one of the first countries at the time to remark that the notion of ‘folklore’ wasn’t explicitly mentioned and to claim it as ‘natural heritage.’ This was an important first step towards the recognition of ‘immaterial cultural heritage’ as something worth preserving. It also carried the implication that immaterial (or intangible) heritage needed to be defined and that it could belong to someone – in this case the Bolivian state. Today, there are seven Bolivian sites considered (material) cultural heritage and five intangible cultural-heritage practices.

Some of these cultural-material sites are from pre-Columbian times: Tiwanaku, Samaipata, the Qhapaq Ñan; others are from colonial times: Potosí, Sucre and the Jesuit missions of Chiquitos. The last one is a natural site: the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park. The intangible Bolivian comprises the Carnaval de Oruro, the Kallawaya culture, the San Ignacio de Moxos celebration, the Pujllay Ayarichi dance of the Yampara and, the latest addition, the Alasitas market.

A country’s heritage is something that the nation as a whole identifies as its own, and which is closely connected to its identity – if not an integral part of its identity. But these heritages are also social constructions, something that became patrimony because it was decided as such. In that sense, it is a fleeting notion, something that represents a nation at a fixed point in time. Because identity is a social construction, it is a dynamic process that responds to the ideals and values of a leading class making it also a political construct. If Bolivia’s patrimony comprises those mentioned above, then it says a lot about how Bolivia sees itself and how Bolivians want to be seen in the world.

It could also be argued that cultural patrimony transcends time and space, that once the status is given it can never be taken back. This is true only to an extent; the national park could disappear because of the Amazon rainforest’s increasing deforestation and environmental destruction. Cultural sites can be destroyed by overexploitation and tourism. It may be counterintuitive, but the heritage of a country is more likely to remain in its intangible practices and traditions. For example, in a really terrible apocalyptic scenario, salteñas could disappear and not physically exist anymore, but the recipe and what it represents in the minds of people would keep on existing.

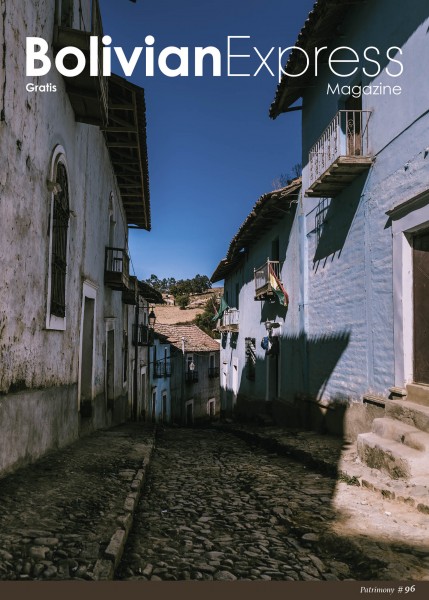

Because of the fragility of the world we live in, there is a real necessity to value, protect and take care of our patrimony, as individuals and as a nation. Bolivia’s heritage is not only items on a list approved by UNESCO, it’s all the food, dances and traditions of the people of Bolivia. It’s the Uyuni salt flats, the 13 national parks that have been recognised, the chullpas. It is everything that surrounds us and that means something to us.

CARNAVAL DE ORURO

Description: Declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, the Carnival of Oruro is the maximum representation of carnivals in Bolivia and is one of the most important in the world. This carnival is an explosion of culture, dance, music, devotion, joy and fun, where more than 60,000 dancers and musicians pilgrim to the temple of the Virgin of Socavon, representing dances from all regions of Bolivia.

Next carnival: February 22-23, 2020. Oruro, Bolivia.

Photo: Sergio Saavedra Patiño https://www.facebook.com/facld/

---

DESTINATION

TIWANAKU

Description: The spiritual and political center of the Tiwanaku culture is one of the most important archaeological sites in Bolivia. UNESCO has declared this site as World Heritage Centre in 2000. There are two museums that are open everyday from 9am to 5pm.

How to get there: There are several tour agencies that organise visits to Tiwanaku but you can also take a minibus from the general cemetery in La Paz city, it takes about 2 hours to get there.

Photo: Fernando Cuéllar for CIAAT

Website: www.tiwanaku.gob.bo

---

HOTELS

ALLKAMARI

Description: This Boutique Eco-Resort & Spa is located 30 minutes from the southern area of the city, in the Valle de las Ánimas. Allkamari is a great place to relax and rest from the city chaos, it has comfortable rooms but the most outstanding aspect is the view of the Illimani which creates an amazing landscape.

Website: www.allkamari.com

Address: Av. Camiraya Nº 222 (Zona Chañoco - Uni) - Valle de Las Animas, La Paz - Bolivia

Photo: Allkamari

---

RESTAURANTS

POPULAR

Description: At Popular you’ll get the best of bolivian cuisine served with a contemporary touch. The taste of each dish takes the best of Bolivian food, flavours and traditions. They also have a selection of craft beers, singani and Bolivian wines. Popular is a ‘must visit’ if you are in La Paz, you’ll have an unforgettable culinary experience.

Address: Murillo street #826

Opening hours: Monday to Saturday from 12:30 to 14:30

Photo: Popular

---

BARS

+591 BAR

Description: The +591 Bar-named after the Bolivian area code- is one of the top places to visit in the city. They offer a new Bolivian cocktail bar experience, their cocktails are inspired by Bolivian flavours, culture, places and stories. The bar is located on the seventh floor (rooftop) of the luxurious Atix Hotel which offers wonderful views of the city.

Address: Atix Hotel. Calacoto, street 16 #8052

Opening hours: 19:00-2:00

Photo: +591 Bar

---

SHOPPING

WALISUMA

Description: Walisuma is a compound word in Aymara that means: ‘The best of the best.’ The store promotes the best producers in our country, carefully selecting their best products and also designing exclusive high-end pieces, allowing you to take extraordinary pieces of Bolivia with you.

Address: Claudio Aliaga street, #1231

Website: www.walisuma.org

Opening hours: 7:30-20:00

Photo: Walisuma

Photos: Rachel Durnford

These ancient funerary structures highlight the importance of conservation

The recent restoration of the chullpas at the Condor Amaya national monument, located in the Aroma province 80 miles south of La Paz, by the Bolivian Ministry of Culture in collaboration with the Swiss government, has renewed interest in the pre-Columbian funerary towers. Chullpas, a rich source of cultural and archaeological information, started to appear in 1200 AD, during the collapse of the Tiwanaku civilization. Although chullpas were mainly constructed by the Aymara people for burials, they were sometimes used by other ethnic groups that were part of the Inca empire (of which the Aymara were one among many). The materials used to construct chullpas vary from place to place, with some Aymara chullpas in the southern altiplano region built from stone and mud.

Carlos Lémuz Aguirre, a member of the Anthropological Society of La Paz, says that ‘the funerary towers were not made for a single individual, but mark a common ancestry – a tomb house for a group of people that were related to common ancestors or the same community.’ This is culturally different from Tiwanakan funeral ceremonies, in which the deceased were interred underground.

Chullpas provide insight into pre-Columbian altiplano mourning rituals. Burial ceremonies lasted anywhere from three to 15 days, during which time the deceased would be honored with food, drink and music. Sometimes the dead would be removed from the towers for rituals to be performed each November.

There is mystery surrounding the construction of these funerary towers, with no definitive answer as to the technologies used that enabled the chullpas to endure through the centuries.

There is mystery surrounding the construction of these funerary towers, with no definitive answer as to the technologies used that enabled the chullpas to endure through the centuries. At a site in the Achocalla municipality southwest La Paz, the chullpas were made with equal parts stone and adobe, but other chullpas were constructed using a range of different processes and different mixes of materials. In the Japan Times, the Greek archaeologist Irene Delaveris speculated that chullpa-makers of the past could have used llama collagen or a local plant to harden the construction materials and enable the chullpas to withstand the centuries, but there are no confirmed theories. There are also as-yet-not-understood regional differences in the sizes and shapes of chullpas, with some being rectangular and others circular.

Historically, there has been misappropriation of South American artefacts, especially in the 20th century when the market for looted antiquities increased sharply. The Bolivian government passed conservation laws in 1906 that claimed ownership of artefacts and restricting digging and exporting without a government permit. Because of the past wholesale looting of its historical patrimony, the Bolivian government is understandably hesitant to allow foreign collaboration on archaeological efforts, but Lémuz points out that conservation needs multidisciplinary teams, making international collaboration especially important considering the lack of archaeologists in the country. ‘Here there is no money for culture and research, so there are no specialised conservationists,’ he says. ‘We do not believe that the restorations that have been made so far are the most appropriate.’ The chullpas at Condor Amaya were in need of restoration because of the erosion of their bases by wind and rain, which weakened the structures. However, their complex construction, and the techniques used to set their adobe bases before the structures were assembled – as well as the type of agglutination used to do so – are still a mystery, and still pose a challenge to archaeologists and conservationists.

Lémuz says there is a shortcoming in the anthropological understanding of pre-Columbian civilisations in Bolivia. He says that the Bolivian Ministry of Culture ‘spends 30 to 40 percent of its budget on communications, talking about the importance of cultural heritage and conservation, and much on tourism, but only 3 percent on actual conservation work.’ Also, Lémuz adds, ‘There is a theme of predatory tourism – sometimes people remove artefacts, dismantle everything and sell them, and even though it is prohibited by law, there is no one to enforce it.’

With the risk the elements pose to the preservation of the cultural heritage at sites such as Condor Amaya, Tiwanaku and El Fuerte near Samaipata – three archaeologically important areas identified by experts as likely to deteriorate – and the lack of protection they are afforded from harmful tourism, the greatest challenge for archaeologists may not be only discovering the ancient technologies that allowed their survival, but simply ensuring they continue to do so.

Photos: Christopher Niklas Peterstam

Walking the ancient Incan road system

In view of the scenic Lake Titicaca a huge ceremony had assembled. Thousands of people dressed in their indigenous garb created a rainbow over the clearing. A stage had been set up adorned with a huge flag of Bolivia, large speakers on each side. The atmosphere was filled with the beating of drums, traditional chants and the smell of a many different barbecues. The excitement was only to be topped by the arrival of the guest of honour, Bolivian President Evo Morales. This was the first ever International Qhapaq Ñan Walk.

The Qhapaq Ñan, known in Western countries as the Incan Road System, was the most advanced and extensive road system within the Americas before the arrival of any European influence. Spanning an amazing 39,900 kilometres, it was enshrined as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014. The road spanned six different present-day countries: Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. Each of these nations had sent state delegates to represent them that day. The symbolic event was aimed at the promotion of tourism, as well as the indigenous cultures around Bolivia and the other participating nations.

Security was noticeable as military police soon began moving people to make way for a motorcade. As soon as Bolivian President Morales stepped out, the air was filled with jubilant cheers. He made his way to the main stage where he was decorated with a brown fedora, a red poncho and wreaths of flowers, and sprinkled with flower petals. Soon all were beckoned towards the path and a huge wave of people made their way onto the ancient trail. The day was perfect for such festivities, blue skies and a bright sun. The path had remained relatively untouched from the days when the Incan tradesmen walked with his llamas carrying goods such as wool, gold and food to different areas of the empire.

Spirits were high as traditional music filled the air. The walk for that day would be only four kilometers, a tiny fraction of the original road. The topography varied the more you walked. Some areas were quite flat and smooth while others wound up hills and were covered with rocks. The altitude was around a breathtaking 3,815 metres, which forced walkers to take short breaks to regain their breath. The walk ended in a small square in which hundreds of people had gathered. The area was filled with music, singing and dancing. A small bonfire was built and vendors sold an array of ice creams and drinks. The crowd soon subsided as President Morales’s motorcade left the area. Thus was the first International Qhapaq Ñan Walk.

Download

Download