PATRIMONY

In 1972, UNESCO adopted the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Bolivia signed the convention, but was one of the first countries at the time to remark that the notion of ‘folklore’ wasn’t explicitly mentioned and to claim it as ‘natural heritage.’ This was an important first step towards the recognition of ‘immaterial cultural heritage’ as something worth preserving. It also carried the implication that immaterial (or intangible) heritage needed to be defined and that it could belong to someone – in this case the Bolivian state. Today, there are seven Bolivian sites considered (material) cultural heritage and five intangible cultural-heritage practices.

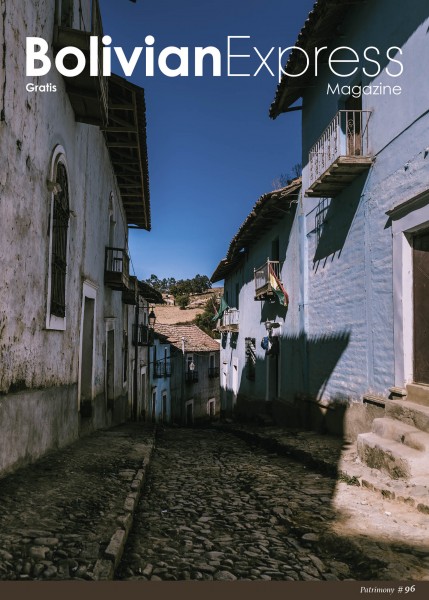

Some of these cultural-material sites are from pre-Columbian times: Tiwanaku, Samaipata, the Qhapaq Ñan; others are from colonial times: Potosí, Sucre and the Jesuit missions of Chiquitos. The last one is a natural site: the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park. The intangible Bolivian comprises the Carnaval de Oruro, the Kallawaya culture, the San Ignacio de Moxos celebration, the Pujllay Ayarichi dance of the Yampara and, the latest addition, the Alasitas market.

A country’s heritage is something that the nation as a whole identifies as its own, and which is closely connected to its identity – if not an integral part of its identity. But these heritages are also social constructions, something that became patrimony because it was decided as such. In that sense, it is a fleeting notion, something that represents a nation at a fixed point in time. Because identity is a social construction, it is a dynamic process that responds to the ideals and values of a leading class making it also a political construct. If Bolivia’s patrimony comprises those mentioned above, then it says a lot about how Bolivia sees itself and how Bolivians want to be seen in the world.

It could also be argued that cultural patrimony transcends time and space, that once the status is given it can never be taken back. This is true only to an extent; the national park could disappear because of the Amazon rainforest’s increasing deforestation and environmental destruction. Cultural sites can be destroyed by overexploitation and tourism. It may be counterintuitive, but the heritage of a country is more likely to remain in its intangible practices and traditions. For example, in a really terrible apocalyptic scenario, salteñas could disappear and not physically exist anymore, but the recipe and what it represents in the minds of people would keep on existing.

Because of the fragility of the world we live in, there is a real necessity to value, protect and take care of our patrimony, as individuals and as a nation. Bolivia’s heritage is not only items on a list approved by UNESCO, it’s all the food, dances and traditions of the people of Bolivia. It’s the Uyuni salt flats, the 13 national parks that have been recognised, the chullpas. It is everything that surrounds us and that means something to us.

Photos: Courtesy of Singani 63

And Director Steven Soderbergh thinks it’s in a class of its own

Singani is the national spirit of Bolivia, created by newly arrived Spanish monks who needed a sacramental wine in the 16th century. By law, singani is crafted exclusively from muscat of Alexandria grapes, grown and distilled at a minimum of 1,524 metres above sea level, which lowers the boiling temperature of the grapes. This unique drink is now being courted by the famed Hollywood director Steven Soderbergh.

Soderbergh first discovered singani while filming his 2008 biopic film, Che, and the director instantly fell in love with the grape brandy and decided to import and promote it in the United States. Singani 63, named for the director’s birth year, has been a project of Soderbergh’s since 2014, when the first boxes of the spirit were delivered to his doorstep. While the drink is available in New York City, as well as some select cities within the United States, the real battle that Singani 63 has been facing is the category of spirit that it has been placed into. Although Singani 63 can be described as a fruit brandy, similar to the Brazilian spirit Leblon Cachaça, the company has been lobbying the US government to place Singani 63 into its own unique category of spirit.

According to the Singani 63 brand manager Stephan Pelaez, ‘We are not fighting for singani to be its entirely new category. Singani is a brandy by the largest definition – any fruit distillate is a brandy – but there are distinct category “types” recognized in the US and internationally. Cachaça is now a recognised category type under rum, pisco is a recognized category type under brandy, as is cognac and almost 14 other distinct fruit distillates.’

The legal confrontation has been going on for around four years at this point. Singani 63 has hired the same lobbying group that represented Leblon Cachaça, which took 10 years of negotiations to be considered a unique product from Brazil instead of generic rum. To this day, Singani 63 is still lobbying the US government to grant them this same privilege. According to Pelaez, ‘Steven [Soderbergh] presented this to the deputy Treasury secretary of the United States. This made our case very clear.’ The brand remains optimistic that it will soon be able to break through the ‘brandy quandary,’ and Palaez says that ‘if we get Singani done in under six [years] that’s not bad at all!’

When speaking about the marketability of singani in the US and Europe, Pelaez says, ‘The leading global industry voices have all recognised that singani is distinct from any other spirit, have added singani to their coveted influential programmes and have written about and recognised the category of singani…. These are the same people who embraced mezcal 20-30 years ago and now across the world everyone is ordering mezcal. So, yes, we are confident singani will be embraced and celebrated the world over. It’s already happening.’

Photos: André Ocampo

The city contains multitudes

Dances, markets, mountains, minibuses, steep streets, contrasts, chaos, zebras, llauchas, tucumanas del prado, la Pérez, cable car, marches, all seasons in one day, marraquetas, salchipapas, Alasitas – these are all part of the paceño way.

16 July is the day of La Paz, a city which has two names, Nuestra Señora de La Paz and Chuquiago Marka, symbolising the many different facets of La Paz. It’s a place where an anticucho can be a street snack or turn into a sophisticated gourmet dish. It’s a chaotic city that does not sleep, where there may be traffic jams at 3:00 am in la Pérez or where it can be impossible to find a taxi on a rainy day. It’s a city full of contradictions where you drink locally produced coffee in sophisticated cafés or enjoy instant coffee with a marraqueta and cheese on a plastic bench in the market.

It’s a city of fighters, where we see many demonstrations in which people have the courage to struggle for what they want, but at the same time it becomes a showcase for great cultural demonstrations and parades.

It’s a place into which everyone can fit, where there’s something for everyone and where you can’t get lost because everything and everywhere always takes you back to the centre. It’s where the Andean, the ancestral, the traditional can be found in everyday things – in the plays, concerts, the cold beer, gin and singani that accompany nights out.

Musicians, writers, painters, sculptures, designers, filmmakers, actors, entrepreneurs, scientists, revolutionaries, activists, rebels, muralists and anarchists – they all find their muses in every corner of the city.

La Paz. The city where people sing ‘Collita’ from the bottom of their heart and dance a kullahuada with grace and gallantry. Every day from 8:00 am, life on the street becomes alive with the caseritas, the zebras, the shoeshine boys, the juice lady, the pasankallas man, the ice cream man, the shoe-repair guy and all the maestritos. Imágenes Paceñas, by La Paz’s ill-fated scribe Jaime Sáenz, is mandatory reading for those who want to understand the city, and who will carry those memories forever.

Download

Download