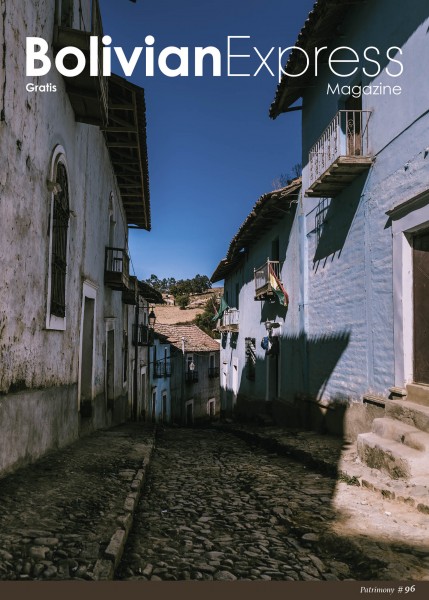

PATRIMONY

In 1972, UNESCO adopted the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Bolivia signed the convention, but was one of the first countries at the time to remark that the notion of ‘folklore’ wasn’t explicitly mentioned and to claim it as ‘natural heritage.’ This was an important first step towards the recognition of ‘immaterial cultural heritage’ as something worth preserving. It also carried the implication that immaterial (or intangible) heritage needed to be defined and that it could belong to someone – in this case the Bolivian state. Today, there are seven Bolivian sites considered (material) cultural heritage and five intangible cultural-heritage practices.

Some of these cultural-material sites are from pre-Columbian times: Tiwanaku, Samaipata, the Qhapaq Ñan; others are from colonial times: Potosí, Sucre and the Jesuit missions of Chiquitos. The last one is a natural site: the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park. The intangible Bolivian comprises the Carnaval de Oruro, the Kallawaya culture, the San Ignacio de Moxos celebration, the Pujllay Ayarichi dance of the Yampara and, the latest addition, the Alasitas market.

A country’s heritage is something that the nation as a whole identifies as its own, and which is closely connected to its identity – if not an integral part of its identity. But these heritages are also social constructions, something that became patrimony because it was decided as such. In that sense, it is a fleeting notion, something that represents a nation at a fixed point in time. Because identity is a social construction, it is a dynamic process that responds to the ideals and values of a leading class making it also a political construct. If Bolivia’s patrimony comprises those mentioned above, then it says a lot about how Bolivia sees itself and how Bolivians want to be seen in the world.

It could also be argued that cultural patrimony transcends time and space, that once the status is given it can never be taken back. This is true only to an extent; the national park could disappear because of the Amazon rainforest’s increasing deforestation and environmental destruction. Cultural sites can be destroyed by overexploitation and tourism. It may be counterintuitive, but the heritage of a country is more likely to remain in its intangible practices and traditions. For example, in a really terrible apocalyptic scenario, salteñas could disappear and not physically exist anymore, but the recipe and what it represents in the minds of people would keep on existing.

Because of the fragility of the world we live in, there is a real necessity to value, protect and take care of our patrimony, as individuals and as a nation. Bolivia’s heritage is not only items on a list approved by UNESCO, it’s all the food, dances and traditions of the people of Bolivia. It’s the Uyuni salt flats, the 13 national parks that have been recognised, the chullpas. It is everything that surrounds us and that means something to us.

Photos: Rachel Durnford

The city’s jazz fans congregate in the new location

Entering the Centro Cultural Thelonious is to be transported to another world, away from the bustling cityscape of La Paz. It’s easy to feel the jazz legacy it’s inherited, with black-and-white photographs and vividly painted portraits of performers hung on every wall, candlelight reflecting off brass instruments to give a warm and intimate atmosphere. Originally established in July 1997, Thelonious is one of the few spaces in Bolivia dedicated to jazz. After an uncertain moment in 2016, when the old club was demolished to make way for another building, there was a struggle in meeting the legal requirements for restoring and moving the jazz club. It was then that the concept of a cultural centre emerged and gained support among musicians and others within La Paz’s small jazz community. Thelonious was reborn as a cultural centre, and it’s now going strong, with both performances and jazz instruction sharing centre stage.

Juan Carlos Carrasco, the current owner who took over the re-establishment of Thelonious, elaborates on what makes it one-of-a-kind. ‘Musicians perform for money, and then they come here to play for enjoyment,’ he says. ‘Lots of jams happen – sometimes we come here at 5:00 am and they’re still playing.’ Carrasco has a cool demeanour, complete with casual white T-shirt and jeans, but it becomes apparent that he has the same energy as the bebop jazz the Centro Cultural Thelonious – and its namesake – is renowned for. He’s engaging when he talks, and, with a youthful glint in his eyes, his passion for jazz is clear. Carrasco jokingly describes his relationship with jazz as similar to falling in love with an ugly girl. ‘It’s like, Oh I don’t know, maybe, I’ll take it, and then you start to really love her, and then by the end it’s like wow!’ he says. Carrasco has a hands-on approach to the Centro Cultural Thelonious and is keen to spend time there helping to develop it. After being enchanted by live music for much of his life, Carrasco is the perfect fit for the cultural centre. His enthusiasm is infectious. ‘I love to see people happy with music,’ he says as he leans forward and gesticulates in a way that makes one believe, as he does, that this is something special.

‘Lots of jams happen – sometimes we come here at 5 am and they’re still playing.’

—Owner Juan Carlos Carrasco

Thelonious’s evolution from bar to cultural centre is particularly important to Carrasco, who described the importance of jazz instruction in the new space. There are instruction studios for music courses, everything from general jazz to big-band music, in the building, in addition to rehearsal spaces for professional musicians. Thelonious provides the classes specifically for amateur musicians who wish to elevate their playing, something that Carrasco hopes will raise the standard of jazz performance in La Paz to a new level. However, he does not underestimate the skill of the musicians Thelonious hosts. ‘You don’t expect this quality of music here, he says. ‘A lot of people think, “Okay, I’ll go,” but after the show’s over, some people are even crying, saying how incredible the performance was.’

I understand this reaction after attending some performances myself. While a group of young musicians perform, the atmosphere is one of raw talent. They clearly relish playing on stage, but they exhibit a sense of shyness that is inevitable considering the importance of the cultural centre to jazz musicians in La Paz. Perhaps the large photograph of Miles Davis staring at the room, his eyes observing the performers with a pensive gaze, is a little intimidating. I also watch Las Vacas Locas, an established Bolivian jazz group with decades of experience. They have a history of performing at Thelonious, so they’re more comfortable displaying their camaraderie in front of an audience. Easy smiles and comments are traded, contrasting with the precise and complex pieces they’re playing, and it’s clear that music is a pure joy for them.

During the breaks, I talk to bassist Christian Bernal, and he relates the more difficult side of performing jazz in Bolivia. ‘The only way that jazz evolves is if we write new music,’ he says. ‘But it’s very hard for people in Bolivia to listen to new, original music.’ Carrasco shares a similar perspective. ‘The audience can’t understand that they must pay to hear music,’ he says. ‘The attitude is “I don’t know the band, I don’t want to pay.” Here it’s, say, five dollars for the cover, so if there are five musicians playing you’re paying one dollar for each. It’s so cheap it’s like they’re playing in the street and, even so, we have protests. The performers need to be big stars to ask for 10 or 15 dollars.’

Despite the struggle for performers and club owners alike, the continued thriving of the Centro Cultural Thelonious demonstrates that there’s a demand for jazz in the city. Carrasco tells of exciting moments in Thelonious’s past, such as when one of Prince’s drummers was in the city and came to the old jazz bar, amazing everyone with his skill. More currently, the cultural centre hosts the annual September Jazz Festival, and Carrasco has talked with excitement about the part he has played in putting on a live production of West Side Story. With a tale not dissimilar to one of a phoenix rising from the flame, it seems that the Centro Cultural Thelonious will continue to be a haven for trainee musicians, journeyman performers, jazz lovers and the occasional jazz maestro in La Paz for many years to come.

The Centro Cultural Thelonious is located at the southern end of Avenida 6 de Agosto; go to @Centroculturalthelonious on facebook.com for more information.

Photos: Christopher Niklas Peterstam

With a worldwide decline in the bee population, Yungas beekeepers protect their hives

Outside Coroico, a small town in the centre of the sparsely populated Nor Yungas Region, a select few begin the process of tearing apart egg cartons and breaking decaying wood into small pieces. They then light the material on fire and place it into a large metal cup, known as a smoker, which apiculturists use to spray bees with smoke in order to calm them. We are here to report on a trend that has been worrying many worldwide, the disappearance of the honey bee. According to Inti Rodriguez, the lead beekeeper, egg cartons and wood have a much ‘softer’ effect on the bees than other materials. Other beekeepers use sawdust, which has a ‘spicy’ effect on the bees, causing them to be more aggressive, and some even use rubber or gasoline, which both negatively affect the bees’ health and contaminate the honey with harmful toxins and a lingering taste.

Soon after, we were ready and clad in protective clothing, carrying our smokers and taking a 20-minute trek into the bush. The path was quite steep at times and often overgrown with brush and vine. The hives were hidden away in such difficult-to-get-to areas for their own protection. This is due to a variety of factors such as fear of robbery and even ignorance about the nature of bees. Doña Julia Mamani, whom the hives belonged to, said, ‘There are also people who are bad or think they are going to die with a bee sting, and that is why they kill them. There are people who even think that bees are bad for plants.’ This misperception has led members of local communities to attempt to find and liquidate the hives, either by fumigation or brute force.

We soon made it to the final portion of the path that led to the hives. There we checked our equipment, suited up in our protective clothing and took a short rest to chew some coca leaves. During this sojourn, Rodriguez and Mamani began to speak about the challenges that bees now face. ‘In the chicken and pig farms, the use of antibiotics and hormones in these animals affects the bees when they consume water contaminated by faeces and rust that these farms discard,’ Rodriguez, said, explaining the dangers that natural resource mining poses to her trade. ‘Mercury is used to amalgamate metals and is thrown into the river, contaminating the water that is also consumed by bees to keep the hive in optimum conditions. The nectar then mixes with that water and the honey gets contaminated.’

The expansion of agricultural areas, especially coca plantations, has led to a variety of problems for the bee population, including worrying levels of deforestation. Natural areas where bees were originally able to go and harvest nectar are being converted into farms and plantations at a very rapid rate. The problem is greater when certain insects that feed on coca plants prompt the use of harmful pesticides. According to Rodriguez, ‘Some herbicides and pesticides used in this area contain glyphosate in its chemical components. In the local market it is known as “bazooka” and anyone can buy it. There is no proper control by SENASAG [the National Service of Agricultural Health and Food Safety Improvement], which is the entity responsible for regulating these substances; in Coroico it is sold in the middle of the street even though they are usually high toxicity chemicals.’

With our masks on, gloves and smokers at the ready, we made the short walk to a small ridge to find two sets of white boxes, stacked one upon the other. As the tin roof was removed from above the boxes, it was revealed that the screens used to protect the hive were too large and had allowed thousands of ants to gain entry. While the honey harvest had not been compromised, the battle that had occurred had left thousands of fallen bees under the hive. Slowly, one by one, Rodriguez and Mamani began removing each screen, examining them for the potential to harvest. The sound of buzzing bees was all around. White smoke billowed from the smoker, creating a fog of frantic bees attempting to defend their hive. The time for harvesting was not ideal. A few more weeks were needed.

This article was made possible through the non-profit organisation Corazón del Bosque. This group has made it a mission to help improve the overall environment in the Nor Yungas region through sustainable agricultural and reforestation projects in several different communities, according to coordinators Eloïse Andre and Romane Chaignau.

https://www.facebook.com/corazondelbosqueCDB/

Download

Download