According to the Bolivian non-governmental organisation Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDIB), nearly a million acres of the country’s land are deforested every year, placing Bolivia among the ten countries in the world with the fastest – and most alarming – rates of deforestation. Soy plantations and cattle ranches, combined with a lack of effective governmental regulations, are responsible for this loss of habitat, most of which has taken place in the last decade. Adding to environmentalists’ concerns was the announcement last year from the country’s minister of hydrocarbons, Luis Alberto Sánchez, who said that the government was considering the fracking of newly discovered gas reserves near Tarija, in the south of Bolivia. Sánchez called this move ‘a paradigm shift’ for Bolivia in the way the country exploits and benefits from natural resources.

The last decade has marked for Bolivia a political, economical and cultural shift from previous governments. Politically, Bolivia established a new paradigm in 2006 with the election of Evo Morales and the adoption of the Vivir Bien doctrine. Pluri-culturalism and respect for the environment are principles enshrined in the Bolivian Constitution. Currently, the decolonisation of education and religion is taking place. Indigenous languages are required in school curricula, and indigenous beliefs are accepted and embraced. Simultaneously, Bolivia has been experiencing economic growth and cultural and social changes which are reframing the current paradigms in potentially conflicting ways.

Bolivia’s continuing economic growth and recent political stability have also put the country on the map as a tourist destination and a land of opportunities for multinationals. Santa Cruz de la Sierra is one of the fastest-growing cities in the world (it was 14th in the latest ranking), and La Paz is regularly featured in travel blogs and magazines as the next place to visit for its vibrant culinary and cultural scenes.

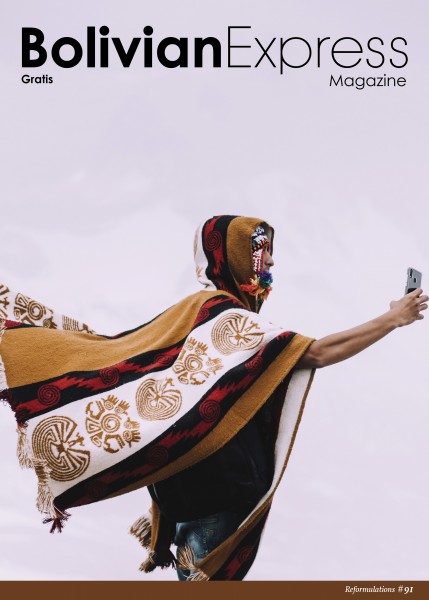

This exposure means that foreign trends are taking root and mutating into their own Bolivian renderings: The world of wrestling has mixed with the world of cholitas, creating a new cultural tradition attracting tourists as well as locals. The way Bolivians eat is also changing: Organic and locally-grown foods are increasingly popular and easy to find. Traditional ingredients are rediscovered and cooked using imported techniques. There is a real renewed appreciation for Bolivian heritage as the popular chakana and carnaval devil’s tattoos attest.

Yes, Bolivia is changing. It is no longer an isolated society recovering from centuries of colonisation by foreign powers. Bolivia is shifting to a new paradigm of a modern plurinational nation and emergent regional power. It’s re-discovering and embracing old and new scientific, spiritual, political and aesthetic ideas which are having a profound effect on the country’s social structure, economy and foreign relations.

But this shift doesn’t come without challenges. If the current deforestation rate continues, Bolivia will have no forest left by the year 2100. The 2006 Vivir Bien paradigm claimed that economic development and respect for the environment are not just compatible, but necessary. And as Bolivia endeavours to responsibly shepherd the exploitation of its natural resources within the global capitalist regime, it also embraces the modern world whilst celebrating and preserving its rich traditional culture.

Photo: Ellie Gomes

A Sunday afternoon in the wrestling ring

As we navigated the bustling Sunday market in El Alto around stalls selling everything from shoe laces to car parts, we were approached by two women dressed in traditional cholita garb. They asked if we would like tickets to watch the cholita wrestling match which would be taking place later that afternoon. It was perfect timing, as we were in El Alto for that very reason. I had been fascinated by the concept of cholita wrestling, having read about its empowering message – something often noted by the women involved – but I was also curious about how it might be exploitative to those same women, as a potentially voyeuristic way for tourists to witness the exotic indigenous ‘other.’

The women offered us a special tourist rate that would give us the opportunity to have our photos taken with the wrestlers, but we opted for the less expensive 40-boliviano tickets – just general-viewing seats, as we didn’t want to draw too much attention to ourselves.

But when we took our seats in the open-air ‘arena’, cordoned off by a wire fence and consisting of a number of plastic chairs all facing towards a central wrestling ring, it was apparent how entirely out of place we were. We thought this event would be overrun with tourists, but it was dominated by locals, particularly families – including, naturally in El Alto, many other cholitas. Halfway through the event, the action stopped and there was an announcement that us extranjeros needed to take photos. Even though we had opted out of it, we found ourselves being photographed by the event staff as we stood alongside the fighting cholitas whilst the rest of the audience watched in amusement.

The event was dominated by locals, particularly families – including, naturally in El Alto, many other cholitas.

There are several locations across El Alto where cholita wrestling takes place. The larger venues, like the Coliseo de 12 de Octubre, feature events that are geared more towards tourists – with some review websites even calling them ‘tourists traps.’ Attendees can book through their hostel or hotel.

But our experience at the wrestling ring was different from what we had imagined it would be. The event started almost an hour late, in classic Bolivian fashion, but there was plenty to observe as we waited in the sun. Vendors passed through the audience selling various snacks whilst young children giggled and played in the open spaces. A rousing soundtrack boomed out from the overhead speakers between regular announcements that the action would start soon.

When it finally started, the action consisted of wrestling between men, wrestling between cholitas and then wrestling between cholitas and men. Notably, there was a complete level of equality between the wrestlers. At no point in this violent, traditionally masculine activity was the femininity of the cholitas mocked or even really considered – though the cholitas maintained it throughout. They fought ferociously, landing punches and throwing each other around. However, they were also victims of the violence too – none of the men exercised any caution as they grabbed the cholitas by their signature braids and pushed them to the ground. Interestingly, the only other tourists – two women who sat behind us – made more comments about the rarity of cholitas wrestling than any of the locals. ‘Oh no, not her pretty dress!’ one of them exclaimed at one point as the wrestler was beaten over the head with a wooden crate.

One local we spoke with emphasised the positive social impact of cholita wrestling. He said that the wrestlers involved demonstrated the strength of women, as many would fight a male wrestler, or even several, proving that women can excel in a violent, forceful sport too.

Though the wrestling was evidently staged, the violence was often genuine-looking enough to cause me to flinch on numerous occasions. But the other audience members were not so easily fazed; they shouted and laughed enthusiastically as the underdog in each match – oftentimes a victim of the referee’s overtly emphasised bias – always managed to fight back.

This wasn’t a typical Sunday-afternoon event; nevertheless, it was clear that the families in attendance were loving the spectacle. As we watched the fighting play out, two small Bolivian boys next to us began fighting in a similar fashion.

By their overt show of strength, the cholita wrestlers embody the increasingly prominent Bolivian idea that women are as equal to men to perform any task.

Recent coverage of cholita wrestling has tended to focus on the reclamation of traditional female power through an overt show of strength, which embodies the increasingly prominent Bolivian idea that women are as equal to men to perform any task. It’s important, however, to remember that cholita wrestling, like most professional wrestling, is a spectacle designed to entertain and generate money. Although they might not be considered ‘real’ athletes, within the makeshift wrestling stadium the cholitas were as powerful as any of the men, and they were admired, supported and heckled by the audience in exactly the same way that the men were.

Photo: Mia Cooke-Joshi

The work of heeding the call of Pachamama

At the edge of the market in El Alto, beyond the never-ending stalls that sell everything you could possibly imagine, is one of the strangest local oddities. To the common tourist, the curious practice of witchcraft and spiritual healing in La Paz is limited to the mercado de las brujas in the centre of the city. But if the tourist asks further, she’ll hear the whispers about ‘where the real witches reside,’ the brujas of El Alto.

Mounted high above the city of La Paz, is the place where those whispers will take you: a line of small green buildings flanked by stone frogs on the sidewalk and small ceremonial fires burning for the Andean deity Pachamama. Inside the walls, are the men and women known as yatiris.

One woman, named Angela (she didn’t want to disclose her full name), sits restfully in a small room filled with Catholic effigies and bright fabrics. Inside her cluttered, but colourful space, she sits in front of a small table displaying a selection of coca leaves, playing cards, tobacco and what appears to be alcohol. With a warm smile she invites me to sit on a low wooden bench and agrees to answer my question about the mysteries of her work.

As I had suspected, one should be wary of using the term brujería or ‘witchcraft’ in reference to Angela’s work, as it has become conflated with spiritual and healing work. At the start of our conversation, Angela clarified the derogatory nature of the label, explaining that a bruja works with el Tío or the devil, to bring about wishes associated with death. ‘I am a yatiri, and spiritual worker,’ Angela asserts, ‘I work with the spirits of Andean cosmovisión in order to bring fortune and well-being to those who seek it.’

‘I am a yatiri, and spiritual worker. I work with the spirits of the Andean cosmovisión.’

—Angela

Becoming a yatiri is considered a birthright that is conditional on three factors: being a twin, having been born with six toes or having been struck by thunder. In Angela’s case, she is caída de rayo.

‘When I was five,’ she says, ‘I lived with my mother on the outskirts of El Alto. We were pastoral herders. One day, it was raining heavily and one of our donkeys escaped, so I went to look for it and thunder struck me.’

If a person survives such an incident, and is able to stand up without help, it is said they are granted the gift of becoming a yatiri. Since that day, Angela has experienced the strangest of visions and dreams, called cosmically by the Andean goddess of the Earth, Pachamama. ‘One is who called to the spiritual path by Pachamama, has no choice but to dedicate their life to this work,’ she says. ‘I tried to go to university, but I kept being brought back to this career path. The life of a yatiri is inevitable.’

Angela speaks about her spiritual work as a doctor or a lawyer would speak of his or her profession. She earns living exclusively by heeding her cosmic calling from Pachamama. Money is integral to yatiri rituals as an offering to the deity. Without it, Pachamama will eat the flesh and soul of the yatiri. Since the spiritual worker lends herself as a medium, she is allowed to profit from the offerings. Although ceremonies and readings require a financial contribution. the price depends on the discretion of the customer. ‘I cannot put a price on my work,’ Angela explains, ‘you must pay according to your faith and the magnitude of the ritual.’

‘I cannot put a price on my work. You must pay according to your faith and the magnitude of the ritual.’

—Angela

Angela and other yatiris who work in the row of square green buildings now belong to an association of spiritual workers. They ask the government for idleland and divide it among them. The yatiris pay taxes and are the rightful owners of their property. ‘The current government has really helped my practice,’ Angela says. ‘I feel there is more support these days. I was even invited by Evo Morales to perform a ritual for him.’ A large and off-centred portrait of Morales hangs above Angela’s head, like an iconic saint.

Her spiritual work is rooted in Aymara customs and beliefs, in which the health and wellbeing of an individual relies upon a medium’s communication with the spirits. Far from being a relic of the past, this Aymara heritage has been strengthened and reconstituted through the government of Morales, which endorses this vitally Bolivian practice. ‘Pachamama calls, and you must listen.’ Angela says. ‘No one can stop the work that we do, because [Pachamama] exists always and within everything.’

Photo: David O’Keeffe

Hiking where the Inca once roamed

Having spent a couple of weeks in La Paz, I felt that I’d adapted to the Andean altitude enough to pack my tent and hike the Takesi Trail, a 40-kilometre portion of a grand system of 30,000 kilometres of road used during the epoch of the Inca Empire that stretched from what is now Santiago de Chile to Pasto in Colombia. I’d prepared for a two-day trek, a somewhat leisurely pace compared to that of the chasquis (Inca messenger runners), who would cover that distance in around two hours.

The Takesi Trail is a tributary to the main Royal Road, one of the two centralised main Andean roads known as the Qhapaq Ñan, a transportation network developed to connect various productive, administrative and ceremonial locations for more than 2,000 years of pre-Incan culture in the Andes. Later, they became instrumental for military conquest and territorial control, both by the Incas and later of the Incas by conquistadors. These roads – which have been recognised by UNESCO as having ‘outstanding universal value’ – have proved remarkably resilient to weather erosion and flooding, conditions that still annually destroy many of the contemporary roads of modern Andean nation-states.

After a short taxi ride from Ventilla to the Takesi trail head near the village of Choquequta, I strolled along an unpaved road overlooking vast terrain occupied mostly by llamas and the occasional farming settlement sitting beneath a glacier. At a point where the road diverged, a man and his donkey came towards me on the path. He was the last person I’d see until the village of Takesi.

A man and his donkey came towards me on the path. He was the last person I’d see until the village of Takesi.

Llamas skipped across my path without paying me much attention – but with 5,000 people a year making the trek, they must be bored by passers-by. After a couple more kilometres, I ascended above the llama pasture towards La Cumbre, a 4,600-metre pass. Clouds rolled in, forcing me to put on my waterproofs.

The route isn’t technical, and it’s easy to follow, but hikers must be prepared for the thin air during the ascent to La Cumbre. It’s a mental and physical battle. My lungs held a fraction of their normal capacity and, after covering 20-30 metres, I was almost breathless. But looking back at my progress gave me a boost of mental energy. Once I reached La Cumbre, thick mist blocked any views, but I was delighted to start heading downhill and I breathed a little easier along the pre-Columbian path. I trudged triumphantly through the clouds, which opened to reveal a startled fox darting across the trail ahead. I followed its grey bushy tail with my eyes until it scurried away once again into the mist.

After descending a few kilometres through open pastures of stone-pocked grass (a landscape that looked a bit like the West of Ireland) and passing an eerily desolate lake, I reached the isolated town of Takesi, the route’s halfway point where walkers can stop for refreshments or accommodation. I carefully picked my way across stones and boulders to cross a river before setting up camp beneath a small waterfall just down from the village.

At 8am the rain stopped tapping on my tent, and it was time to set out again. The trail was becoming discernibly more tropical as I struggled for an hour or so down a lengthy section of paved Inca road that was a marathon of wet slippery stones. Although the trail has been resilient to weather erosion, it was also incredibly dangerous with a deathly steep drop for anyone who falls down the valley side. But by gripping my feet on tufts of grass, I was able to manoeuvre through this section with only a few stumbles.

Later, the rain clouds cleared and the gargantuan landscape revealed itself. Tall mountains surrounded me; narrow gully streams rushed with the recent days downpour. Instead of looking behind for motivation, I was filled with excitement to see what was ahead. The previous day’s rocky slopes had transformed into the lush forest of the Yungas, which was beginning to explode with the colours of subtropical plants. Butterflies surrounded me and landed around my feet.

The previous day’s rocky slopes had transformed into a lush forest that was beginning to explode with the colours of subtropical plants.

With the mist now beneath me, I had to remind myself to stop and take in the amazing scenery. I looked down over silvery clouds that had gathered in green valleys, and I spotted bright flowers along the thin winding track. Where a river blocked the route, fallen trees served as a bridge. The trek was simple and beautiful from here, particularly with the abundance of oxygen and sub-tropical warmth. After crossing the Takesi River, I knew there were only a couple of hours left in my trek, so I paused regularly and gawked at the scenery – abandoned buildings and a miners’ post – before exiting the Inca trail onto a paved road that ran to Yanacachi. The final kilometres offered stunning views of mountains towering above me and the steep drop of the valley below. After passing through an unexplainable cliffside propiedad privada checkpoint, I was on the home stretch and felt exhausted. A roaming dog accompanied me to the sloping town of Yanacachi until it was shooed away by a restaurant owner who piled up a heavy plate of fried chicken, rice and plantain in front of me while I reflected back on the journey. I found a cheap but comfortable hotel room a few doors down and prepared to settle down for the night. After I finally changed out of my hiking gear and started to relax, I drank an ice cold beer in the warmth of my bed before I was overcome by tiredness and fell asleep.

Download

Download