According to the Bolivian non-governmental organisation Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDIB), nearly a million acres of the country’s land are deforested every year, placing Bolivia among the ten countries in the world with the fastest – and most alarming – rates of deforestation. Soy plantations and cattle ranches, combined with a lack of effective governmental regulations, are responsible for this loss of habitat, most of which has taken place in the last decade. Adding to environmentalists’ concerns was the announcement last year from the country’s minister of hydrocarbons, Luis Alberto Sánchez, who said that the government was considering the fracking of newly discovered gas reserves near Tarija, in the south of Bolivia. Sánchez called this move ‘a paradigm shift’ for Bolivia in the way the country exploits and benefits from natural resources.

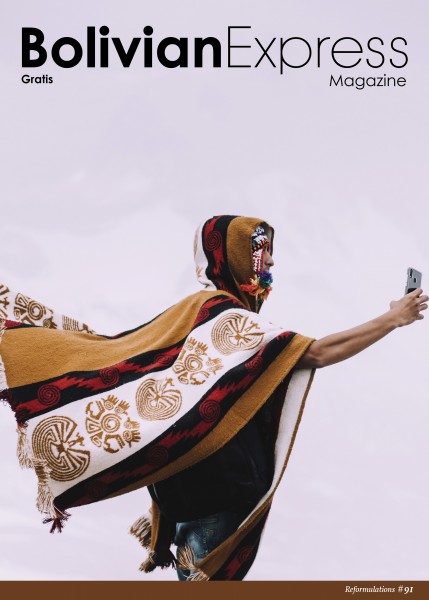

The last decade has marked for Bolivia a political, economical and cultural shift from previous governments. Politically, Bolivia established a new paradigm in 2006 with the election of Evo Morales and the adoption of the Vivir Bien doctrine. Pluri-culturalism and respect for the environment are principles enshrined in the Bolivian Constitution. Currently, the decolonisation of education and religion is taking place. Indigenous languages are required in school curricula, and indigenous beliefs are accepted and embraced. Simultaneously, Bolivia has been experiencing economic growth and cultural and social changes which are reframing the current paradigms in potentially conflicting ways.

Bolivia’s continuing economic growth and recent political stability have also put the country on the map as a tourist destination and a land of opportunities for multinationals. Santa Cruz de la Sierra is one of the fastest-growing cities in the world (it was 14th in the latest ranking), and La Paz is regularly featured in travel blogs and magazines as the next place to visit for its vibrant culinary and cultural scenes.

This exposure means that foreign trends are taking root and mutating into their own Bolivian renderings: The world of wrestling has mixed with the world of cholitas, creating a new cultural tradition attracting tourists as well as locals. The way Bolivians eat is also changing: Organic and locally-grown foods are increasingly popular and easy to find. Traditional ingredients are rediscovered and cooked using imported techniques. There is a real renewed appreciation for Bolivian heritage as the popular chakana and carnaval devil’s tattoos attest.

Yes, Bolivia is changing. It is no longer an isolated society recovering from centuries of colonisation by foreign powers. Bolivia is shifting to a new paradigm of a modern plurinational nation and emergent regional power. It’s re-discovering and embracing old and new scientific, spiritual, political and aesthetic ideas which are having a profound effect on the country’s social structure, economy and foreign relations.

But this shift doesn’t come without challenges. If the current deforestation rate continues, Bolivia will have no forest left by the year 2100. The 2006 Vivir Bien paradigm claimed that economic development and respect for the environment are not just compatible, but necessary. And as Bolivia endeavours to responsibly shepherd the exploitation of its natural resources within the global capitalist regime, it also embraces the modern world whilst celebrating and preserving its rich traditional culture.

Photos: David O’Keeffe & Ellin Donnelly

A coeliacs guide to the city

A spectre haunts La Paz – the spectre of gluten. Unfortunately, the majority of restaurants and street food vendors in La Paz have not tried to exorcise it. The estimated 0.4 percent of the Bolivian population that suffers from coeliac disease is haunted by the temptation of gravy filled salteñas, cheesy llauchas and the taunting smell of choripan.

Gluten is what makes wheat flour puff up and bind well when heated to make the best pastries, or thicken a steaming soup. Over time, It has understandably become a go to ingredient for chefs and bakers. This, however, does not bode well for coeliacs, who are unable to digest proteins in wheat, barley and rye.

South America has the lowest occurrence of people with coeliac disease in the world. The Bolivians who are most likely to have this autoimmune disease are those of European descent, particularly German Mennonites. The number of diagnosed coeliacs, though, may rise with growing awareness and testing for the disease, particularly since gluten free diets have become a health trend.

South America has the lowest occurrence of people with coeliac disease in the world.

So what tasty delights does La Paz have to offer for people who don’t want to join in on life’s feast? Fortunately there are a several great options:

Anticuchos: This snack is easiest to spot by looking for leaping flames in the night on a city sidewalk, erupting around a woman who tends to a delicious simple skewer of lightly marinated beef heart and potato, served with a peanut sauce. Not only is cow heart an incredibly lean and healthy piece of meat, it also has a great texture.

Not only is cow heart an incredibly lean and healthy piece of meat, it also has a great texture.

Tripa: For the more adventurous, or desperate, Bolivian coeliac there’s tripa: slightly chewy, almost bitter fried cow intestine that is harder to find than other commonly available street snacks.

Pasankallas: Bolivia’s sugary alternative to regular popcorn, is found in oversized plastic bags on the streets of the city, waiting for you to break through the crisp outer layer of sugar on a piece of giant puffed corn and crunch on the starchy fluff.

Assorted Dried Foods: Great to stabilise blood sugar levels when consumed with freshly squeezed orange juice. These dried foods stalls offer a variety of treats: dehydrated banana, corn, peanuts, berries and beans, usually accompanied by a salt shaker to give them a flavour boost.

Pot Luck: Almost anywhere in La Paz you’ll find silver pots covered in rain sheets and surrounded by tiny seats. This is coeliac pot-luck, with no advertising of what’s on offer. It could be gluten filled sopa de fideo or, if you’re lucky, a luscious side of pork served with plátanos and potatoes. Either ask the vendor or spy on others plates.

Ceviche: This delicious dish comes in a variety of styles around the city, but the foundation is fresh fish cooked in the acidity of lime juice in a process known as ‘denaturation.’ A particularly delicious option is the Ceviche Show jeep parked facing the Alcala Hotel on the corner of Plaza España. It serves ceviche mixte or traditional with a side topping of crispy maize. Sit in the shade of a large tree or grab a bench to enjoy some of the best coeliac street food in the capital.

Photo: Drew Graham

Navigating the challenges of adapting to a new culture

The majority of Koreans who live overseas have settled in China, the United States and Japan. Lately, however, there has been a small, but increasing number of South Koreans who come to Bolivia for short term development work, and an even smaller number who et down roots in the country and become part of the Korean diaspora in Bolivia.

Korea’s recent links to Bolivia led to the naming of an eight-lane suburb road in Santa Cruz as ‘Avenida Corea’ in 2017, to celebrate Korean investments in development projects. The two countries have had diplomatic relations since 1965 and the influence of Korean culture and businesses in Bolivia has grown significantly given the growth of Korea’s ‘tiger economy.’ The Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), which originated as a recipient of foreign aid, has now become an international donor to assist projects in developing countries and serves as a bridge for young Korean volunteers to Bolivia.

Despite the growing economic bonds between both nations, what can these cultures learn from each other outside the realms of commerce? With this question in mind, we interviewed three Koreans living in La Paz to get their perspective on the similarities, differences and experiences of the two cultures.

It seems the most common difficulty in settling in to Bolivia is also one of the most predictable cultural contrasts: food. Sue Yong Park, a KOICA volunteer who has been living in Bolivia for less than two years, explains that Korean cuisine features fermented foods, like the famous cabbage dish, kimchi that are hard to come by in La Paz. In the absence of the comfort foods, she prefers to cook Korean food at home. Although Park hasn’t become accustomed to Bolivian dishes, she professes a fondness for the eastern Bolivian dish majadito.

The most common difficulty in settling in to Bolivia is one of the most predictable cultural contrasts: food.

Soohyeon An and Hangyeol Choi, who are KOICA interns in La Paz, spoke of ‘suffering from cilantro,’ a non-existent ingredient in Korean recipes that tastes like soap to those who are genetically hypersensitive to the taste of aldehydes in cilantro, which is about 20 percent of East Asians. Despite the hurdles, however, food has served as a way of exchanging cultures for Korean expats. They cook Korean food for Bolivian friends, who are more adaptable to a change of cuisine, and have a newfound respect for the art of salteña making after taking a local cooking class.

Soohyeon An and Hangyeoi Choi have been ‘suffering from cilantro.’

An and Choi like how Bolivians are keen to share their national culture and they like to share their own Korean roots whenever the opportunity arises. Until the interview for this article, both of them thought the K-Pop fever in Bolivia was only something organised by the Korean embassy. They hadn’t heard of the K-Pop festivals in La Paz, and asked if they could participate. After only a month of being in Bolivia, An sings along to reggaeton without understanding the lyrics. Music, like food is a cultural element that is prone to immediate enjoyment or rejection.

Another cultural element that has been hard for Koreans to adapt to in Bolivia are the instances of unintentional or deliberate racism in the country. On the soft side of these incidents ‘they love to call us “China”’ says An. Choi doesn’t mind the Chinese references, but recalls being told to ‘get the hell out of my county’ by people on the street or in the market on more than one occasion.

One part of Bolivian culture, however, that inspires admiration is the patriotic spirit of Bolivians and the pride they take in their traditions. ‘You guys love your culture, so preserve that well,’ Choi says. ‘In Korea we developed so fast and so quickly that we didn’t think about the importance of preserving our culture, so we destroyed a lot.’ Sue Yong Park agrees and says she will miss the traditional dances of Bolivia. ‘Many people in Korea don’t know about [our traditions] and do not think we need to respect Korean culture,’ she says. ‘Korea has many other cultural attributes that are more beautiful than K-Pop.’

Although Bolivia is developing rapidly, historical icons and traditional ideas are often integrated into the country’s growth. The Bolivian Space Agency named its satellite The Túpac Katari 1 in 2013, showing the drive to preserve a specific heritage as the country changes economically and demographically with the influence of immigrants. Looking to the future, Choi says that Bolivians ‘have a high concept of climate change... more than Koreans. We have just started talking about climate change, but people here already know about it,’ she says. This is especially true due to Bolivia’s vulnerability to climatic changes. ‘There are a lot of limitations,’ Choi adds, ‘but if Bolivians keep trying, they will have a bright future.’ Her experience has shown that the stereotype of the lazy Latin American worker is not true. She thinks Bolivians, like Koreans, are hard workers.

Photos: David O’Keeffe & Rodrigo Jimenez

Tattoos are coming up big in Bolivia

There has been a long gap in the history of tattooing in Bolivia. Mummified remains found in Bolivia and Peru show that the decorative art was once a common practice in the region. People would use cactus spines to insert charcoal powder under their skin to create figures and designs. But with the rise of the Inca Empire in the 15th century, tattoos fell out of favour. The Inca belief in bodily perfection, and the later conquest and colonisation by Catholic Spain (and its conservative attitude and antipathy toward indigenous culture), help explain tattooing’s long historical absence in Bolivia.

Now, however, tattoos in Bolivia have become much more mainstream. Once associated with only criminals and lowlifes, tattoos are now adorning the bodies of Bolivian sports stars and other popular culture figures, who have helped normalise the practice. And now regular Bolivians display elaborate works of art on their bodies. Tattoo artist Rodrigo Jimenez from Eternal Tattoo, a studio in La Paz’s Sopocachi neighbourhood, says, ‘You’re often misjudged as a bad person’ if you have tattoos. He recounts his aunt’s grim reaction when she first saw one of his tattoos on his hand. Luckily, though, it was of his dog. ‘It [would be] different, though, you know, if I had a skull’ instead of a dog, he says. But Jimenez isn’t a ‘typical’ tattoo artist. He’s an animal lover who only uses vegan ink, and during his ‘Claws, Paws and Ink’ event in January, in which he inked ten animal tattoos for clients, he raised 5,560 bolivianos for the La Senda Verde wildlife sanctuary.

While the Bolivian tattoo scene is still small, it’s been given a boost in recent years by several tattoo conventions, which have ‘helped a lot for the growth of new artists,’ says Rodrigo Aguilar Cruz of the Ritual Arte y Tattoo studio, also in Sopocachi. ‘I came to see tattoos as something significant, and to respect the people who make them.’ Eternal’s Jimenez says the first tattoo convention he attended, in 2003, ‘changed the game in Bolivia,’ at a time when not only were tattoos generally considered unacceptable, but access to machines and international tattoo artists for inspiration was incredibly rare. Now, though, international influence has popularised the Bolivian tattoo scene, particularly Instagram accounts and TV shows that feature tattoo artists and their work, expanding the culture rapidly.

‘I came to see tattoos as something significant, and to respect the people who make them.’

—Tattoo Artist Rodrigo Aguilar Cruz

Global influence inspired Jimenez, now 32, to become a tattoo artist; when he was seven years old, he saw a tourist covered in tattoos. It was ‘a very important moment in my life,’ he says, leading him to pursue an apprenticeship at a tattoo studio 12 years ago.

Jimenez says that early on with his business, his clients were mainly tourists who ‘fell in love with the culture’ of Bolivia and wanted Inca-inspired drawings of suns and moons to be inked into their skin. Both he and Aguilar Cruz see this as a mark of respect for Bolivian culture and history, although Aguilar Cruz’s designs run in what he calls a ‘psychedelic surrealist’ style. He combines realism with abstraction, psychedelic colours with monochromatic black and white, antiquity with modernity, and a street-art style with depictions of pre-Columbian ruins.

There’s a distinctly Bolivian influence in both artists’ respective oeuvres. The culture here provides tattooists and clients with ‘much to exploit,’ because ‘each department [in Bolivia] possesses its own cultural identity,’ Aguilar Cruz says. ‘Western Bolivia’s style of tattooing brings with it a variety of symbolism that identifies it with Tiwanacota culture.’ Jimenez agrees: ‘Yes, it’s completely different,’ he says when comparing the richness, diversity and symmetry of Andean designs to the figurative art common in Bolivia’s lowland regions, where people are more likely to get designs related to their surroundings, like cats, leaves or flowers.

An increasingly diverse and talented cohort of artists is driving the tattoo scene forward in Bolivia, with a unique take on the once-disreputable art.

According to Aguilar Cruz, tattoos have ‘become a fashion for everyone without distinguishing skin, colour or age.’ But they are still a relatively rare fashion trend. They remain expensive for most Bolivians, and equipment must be imported from abroad. Nevertheless, an increasingly diverse and talented cohort of artists is driving the tattoo scene forward in Bolivia, with a unique take on the once-disreputable art.

Tattoo by Rodrigo Jimenez

Download

Download