According to the Bolivian non-governmental organisation Centro de Documentación e Información (CEDIB), nearly a million acres of the country’s land are deforested every year, placing Bolivia among the ten countries in the world with the fastest – and most alarming – rates of deforestation. Soy plantations and cattle ranches, combined with a lack of effective governmental regulations, are responsible for this loss of habitat, most of which has taken place in the last decade. Adding to environmentalists’ concerns was the announcement last year from the country’s minister of hydrocarbons, Luis Alberto Sánchez, who said that the government was considering the fracking of newly discovered gas reserves near Tarija, in the south of Bolivia. Sánchez called this move ‘a paradigm shift’ for Bolivia in the way the country exploits and benefits from natural resources.

The last decade has marked for Bolivia a political, economical and cultural shift from previous governments. Politically, Bolivia established a new paradigm in 2006 with the election of Evo Morales and the adoption of the Vivir Bien doctrine. Pluri-culturalism and respect for the environment are principles enshrined in the Bolivian Constitution. Currently, the decolonisation of education and religion is taking place. Indigenous languages are required in school curricula, and indigenous beliefs are accepted and embraced. Simultaneously, Bolivia has been experiencing economic growth and cultural and social changes which are reframing the current paradigms in potentially conflicting ways.

Bolivia’s continuing economic growth and recent political stability have also put the country on the map as a tourist destination and a land of opportunities for multinationals. Santa Cruz de la Sierra is one of the fastest-growing cities in the world (it was 14th in the latest ranking), and La Paz is regularly featured in travel blogs and magazines as the next place to visit for its vibrant culinary and cultural scenes.

This exposure means that foreign trends are taking root and mutating into their own Bolivian renderings: The world of wrestling has mixed with the world of cholitas, creating a new cultural tradition attracting tourists as well as locals. The way Bolivians eat is also changing: Organic and locally-grown foods are increasingly popular and easy to find. Traditional ingredients are rediscovered and cooked using imported techniques. There is a real renewed appreciation for Bolivian heritage as the popular chakana and carnaval devil’s tattoos attest.

Yes, Bolivia is changing. It is no longer an isolated society recovering from centuries of colonisation by foreign powers. Bolivia is shifting to a new paradigm of a modern plurinational nation and emergent regional power. It’s re-discovering and embracing old and new scientific, spiritual, political and aesthetic ideas which are having a profound effect on the country’s social structure, economy and foreign relations.

But this shift doesn’t come without challenges. If the current deforestation rate continues, Bolivia will have no forest left by the year 2100. The 2006 Vivir Bien paradigm claimed that economic development and respect for the environment are not just compatible, but necessary. And as Bolivia endeavours to responsibly shepherd the exploitation of its natural resources within the global capitalist regime, it also embraces the modern world whilst celebrating and preserving its rich traditional culture.

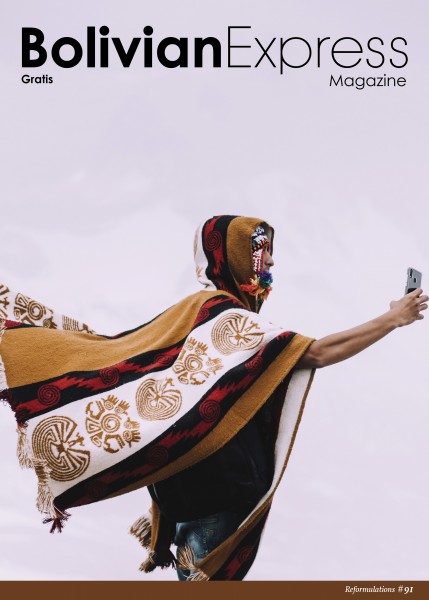

Photo: Elin Donnelly

Mural: Knorke Leaf

The year 2019 was proclaimed the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IYIL) by the United Nations in 2006. The aim of this year’s celebration, is to raise awareness of indigenous languages and cultures that face the threat of fading entirely due to political and social isolation. On 1st February, President Evo Morales gave a speech to kick off the year, which is organised by UNESCO. Speaking before world leaders, Morales stressed the global significance of indigenous languages, not only as means of communication, but as vessels for culture and identity:

‘Around 6,700 languages are currently spoken around the world, of which 40 percent are in danger of disappearing completely. The majority of this 40 percent are indigenous. By losing these languages, we run the risk of losing our cultures and understanding. Each language reflects the culture of the society that created it… the loss of a language just as much marks the loss of a worldview, and the impoverishment and diminishment of [human intelligence as a whole].’

IYIL will take place at a crucial time for global linguistic diversity. In 2004, a study conducted by British linguist David Raddol and published in Science, predicted that 90 percent of the world's languages will become extinct by 2050. The term ‘language extinction’ refers to a language that loses its last living speaker. These linguistic dead ends will have cultural consequences that are difficult to predict and perhaps even harder to measure.

Due to globalisation, many people think of speaking a second global language as something essential. Travel and international business are not only available on a growing scale, but have become common expectations. As people migrate towards international hubs and globalised urban centers, their mother tongues can fall out of use through generations. But indigenous languages have faced a more severe threat: colonisation.

In most of Latin America, colonisation used catholicism and the Spanish language as a means of imposing a certain ideology, and a way to control the cultural expressions of indigenous people. The power of linguistic subjugation is summarised by American writer Philip K. Dick; ‘The basic tool for the manipulation of reality is the manipulation of words. If you can control the meaning of words, you can control the people who must use them.’

In spite of the trend towards naturally and unnaturally caused language extinction, for the past ten years Bolivia has been actively combatting this issue with legislation. Only 60 percent of the 11 million people who live in Bolivia speak Spanish as their native language. This means 40 percent of the population, has an indigenous language as its mother tongue. Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution and its General Law of Linguistic Rights and Policies require that all governmental departments use at least two languages, one of those being Spanish and the other an indigenous language of the region. These pieces of legislation not only recognise the relevance of indigenous communities in Bolivia, but also ensure that their languages are actively maintained on an official level.

Bolivia has also lead significant reform in the context of education. For years, Bolivia faced a crisis of illiteracy that affected the country’s indigenous groups. The fact that the state only recognised Spanish as the official language of the nation’s system of education greatly limited the access of indigenous students to education, which exacerbated the issue. The 1994 education law aimed to diverge from imposed Western schooling techniques, and most importantly, promote the teaching of an indigenous language alongside Spanish in schools. A law signed by Morales in 2010, known as ‘Law 070’, reinforces those principles with a focus on decolonisation.

Bolivia officially recognises 36 indigenous languages, a number that may soon grow to 39 as more communities petition to be included in the Constitution. Of these languages, however, the three most spoken after Spanish are Quechua, Aymara and Guaraní. Though Guaraní is primarily spoken in Paraguay, the Guaraní people are spread over several countries in Latin America, including the southeast of Bolivia. Like many indigenous languages, Guaraní did not have its own writing system before colonisation. This is not to say that the Guaraní don't have a literature of their own. They have a rich oral tradition in which stories are passed down by communities from generation to generation.

Irande is the first novel to be written in Bolivia entirely in Guaraní. It was penned by Elio Ortiz Garcia, an Isoseño-Guaraní from the Gran Chaco. Ortiz had previously written about Guaraní social issues, such as healthcare, determined to give his people a voice. Although Irande is a written piece of work, it reflects the storytelling techniques and philosophical values that are typical of Guaraní tradition.

Since the implementation of Law 070, there has been a strong government push for schools to adopt indigenous languages,which Florentino Manuel Aquino, a Guaraní teacher in Santa Cruz, believes is key for legitimising both indigenous languages and the Plurinational State. But to learn a language like Guaraní, one must also understand the culture and philosophy that goes along with it. ‘The Guaraní have a very close connection to nature and the cosmos,’ Manuel says. ‘Spirituality is very present in our lives.’

According to him, language and identity are very tightly intertwined, especially when one has had to struggle to keep these elements alive. Manuel believes communities fight to maintain their language and culture ‘because language is our soul.’ He celebrates the International Year of Indigenous Languages as a worldwide statement. ‘Decolonisation should mean respecting various cultures and identities,’ Manuel says. ‘Indigenous languages have a worldwide significance.’

Even with new legislation, Manuel admits that younger generations do not see the importance of maintaining indigenous languages and do not consider it useful. It is true that, with globalisation, language extinction seems an inevitable problem, but one could argue that this is why the International Year of Indigenous Languages has come at a pivotal moment. It conveys the universal message that all cultures and languages should be respected and honoured and that we must conserve indigenous languages to avoid losing a part of global heritage. In the words of Nelson Mandela, ‘if you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.’

For more information on the International Year of Indigenous Languages, and to find out how to get involved, visit: https://en.iyil2019.org

Photos: Alicja Hagopian

La Paz’s renowned cultural café is just one aspect of the region’s independently produced local food renaissance

Café MagicK was founded in 2014 by husband-and-wife team Stephan Gamillscheg and Alison Masiel Pino Pinto, two years after they married. When he left Denmark to work for an NGO in La Paz, Gamillscheg found an vibrant artistic and cultural crowd here, but there was a lack of spaces for people to congregate and express themselves. Coming from Denmark, which has a notable café culture, he was surprised to find that the city was surrounded by rich coffee-growing regions but an absence of good quality coffee being made here. And so Café MagicK was born. But despite its name, MagicK is much more than just a café; it’s also a bar, with live music and other events – and above all, incredible food. MagicK’s dishes are seasonal and experimental, everything from healthy spins on traditional meals like pique macho to exquisite culinary creations featuring unexpected flavour combinations, such as the hongos ostra MagicK (oyster mushrooms, tempeh, polenta, manioc and various colourful vegetables, finished with a fragrant white wine sauce).

Gamillscheg considers MagicK to be one of the front runners of the city’s burgeoning culinary scene, especially because of the restaurant’s vegetarian-based menu (save for a few fish-based items). Gamillscheg is a vegetarian himself, and he wanted his restaurant to promote the same healthy lifestyle. That’s no small task in Bolivia, whose residents traditionally have a meat-heavy diet. In fact, new customers sometimes cannot understand how meat does not feature on MagicK’s menu. But people are warming up to vegetarianism, Gamillscheg says, even though ‘the tempeh or the mushrooms cost above the price of the finest fillet.’ Since the restaurant’s opening, similar establishments have opened around the city, and MagicK itself will undergo an expansion in the near future – and Gamillscheg is even considering adding another location in the municipal theatre, reflecting La Paz's growing appetite for a bit of MagicK.

From the start, the owners knew that they wanted to keep the menu as organic as possible and serve paceños unfamiliar and exciting ingredients. Gamillscheg says that the menu constantly changes, describing it as a ‘conscious fusion kitchen’, combining Bolivian produce and international techniques. For such special products, customers are willing to pay a higher price, as that is what sets MagicK apart. A good client-producer relationship is crucial, because on such an intimate scale a business is essentially codependent. Not only do the producers need their clients in order to keep their business afloat, but restaurants like MagicK need to be able to rely on their purveyors to stock their pantries. Due to the nature of small-scale agriculture, certain factors will occasionally hinder production, so it is essential to have a flexible kitchen that is able to adapt to its resources. One workaround is the popular and bountiful sharing platter, which doesn't constrain the kitchen but instead allows it to improvise with whatever ingredients are available that day.

For Gamillscheg, working with independent producers can be challenging and costly, but ultimately it reflects the ethos which he and Pino believe in, with regard to health, culture and the environment. We visited several of MagicK’s producers and talked to them about the ups and downs of local, organic and sustainable farming, and why it just might have the potential to take on the agroindustry.

PRAAI

PRAAI (Promoción Agroalimentaria Inclusiva, or the Promotion of Inclusive Farm to Table) is a social project that promotes organic and sustainable production and rights for its producers. It provides a variety of produce, most notably baby vegetables, which gives PRAAI a unique position in the market. The organisation’s eco-friendly philosophy is threefold: First, the nutrition for the plants which its members produce must come from compost. Second, no pesticides or chemicals are used to treat diseases; instead, natural products are used as alternatives. Third, in order to reduce water consumption, water-collection systems must be used as well as autonomous filtration and distribution networks.

We visited Noemi Mamani Pucho, a university student who participates in PRAAI, at her greenhouse in El Alto, where she is developing her thesis on the mycorrihizal (symbiotic) relationship between certain fungi and the roots of plants. She raises yellow cherry tomatoes that are sweeter than the usual red cherry tomatoes, which make them popular with buyers such as MagicK. She’s currently improving her greenhouse so that her tomatoes will grow year-round. Mamani’s colleague and fellow PRAAI member, Tito Valencia Quispe from the Universidad Pública de El Alto, is also working on his own crops. ‘It’s a great thing for an agronomist to have their own greenhouse,’ he says. ‘For me, the greenhouse is where I can de-stress.’ Along with leafy greens and a variety of herbs, Valencia grows strawberries and, of course, baby everything – radishes, carrots, beetroots, among others.

ANDEAN CHAMPIONS

Husband-and-wife duo Abel Rojas Pardo and Dunia Verastegui Baes founded Andean Champions, an oyster-mushroom farm, nearly ten years ago. They didn’t have an auspicious start, as at the end of their first year, their yield fell far short of their goal. A harsh winter brought a frost which killed everything they had worked for. It was a huge blow, Rojas says, and they realised that they had to commit even more to their enterprise. Two years later, Verastegui decided to devote herself full time to the enterprise. The business is a constant experiment, staffed largely by students with an environment of curiosity and a drive to improve.

When I visited Andean Champions farm outside of La Paz, I expected to encounter a typical greenhouse. But mushrooms, unlike fruits or vegetables that sprout from seeds or roots, originate from spores in a laboratory-like setting. If this conjures up images of scientists in a lab coats, you're on the right track. The process begins in a controlled environment in which oyster-mushroom spores are incubated before they are inserted into containers of digestible materials like sawdust or straw, into which they grow their roots, or mycelia. The containers are then moved into an area with high humidity and controlled lighting, which then trigger the production of fruit bodies – the edible part of the organism – which erupt through small holes of the containers in clusters called troops. Once these troops emerge, the oyster mushrooms will be ready for harvesting in about a week.

Mushrooms aren’t hugely popular in Bolivia, so it’s a tricky business to be in. While some people are eager to snatch up the product wherever they can find it, business can be fickle. Many of Andean Champions’ clients are restaurants, and when a dish accommodates rarer items like a fine mushroom, business is good. But if that dish suddenly disappears from the menu, the producers' livelihood disappears along with it. This is one of the difficulties they face as smaller-scale producers, alongside the complications that go hand in hand with learning the fundamentals of trade for the first time. Nonetheless, Rojas is optimistic about the future and hopes to increase production significantly in 2019. His advice on starting a business is simple: ‘The most important factor isn’t money or land – it's the decision to just do it.’

TIERRA CONSCIENTE

‘We can't continue to form a society based upon animal produce, and we have to find a alternative source of protein,’ Tierra Consciente’s founder, Marcos Nordgren Ballivian, says. Four years ago, Nordgren founded the company, which ferments soy, beans and peanuts to produce a variety of tempeh that contains high levels of probiotics, calcium and vitamins, along with a healthy dose of protein. Nordgren has since branched out into other unconventional foodstuffs which are particularly revolutionary in the Bolivian market. In addition to a vibrant assortment of vegetables such as yellow zucchini, mushrooms and herbs, Tierra Consciente produces a gluten-free long-life bread made from potatoes in lieu of wheat. It’s dehydrated for a week before packaging, ensuring a months-long shelf life.

But Nordgren’s vision for local, independent production does not come without its challenges. He says that the largest difficulty lies with logistics – that is, delivery, distribution and price negotiation. Buyers are used to purchasing en masse, a practice that is in opposition to the essence of small scale production. Furthermore, consumers have become accustomed to a certain price range which is only feasible within the framework of big industry. When small businesses attempt to function within that traditional framework, prices are often hiked by middle men while the businesses themselves are left with, pardon the pun, peanuts. But who is to blame? As Nordgren puts it, ‘We can blame industries, we can blame governments, but at the end of the day it is an issue of the producer-consumer model.’ Moreover, it is a daily struggle for producers to stay organic when it is far easier and often cheaper to use chemical pesticides and fertilisers. Nordgren also says that society awards large-scale producers for being wasteful, because it's easier to sell a product which is packaged – and yes, that packaging is almost always plastic.

Independent producers don’t just grow their products – they also have to teach themselves the ins and outs of the business. But despite all the demands, Nordgren finds his job stimulating and feels privileged to be able to do what he does. Though the existing market may be tough to crack, buying local offers unique organic and sustainable options, and producers like Nordgren are working hard to make this reality more accessible in the future.

Download

Download