WOMEN - VOLUME 2

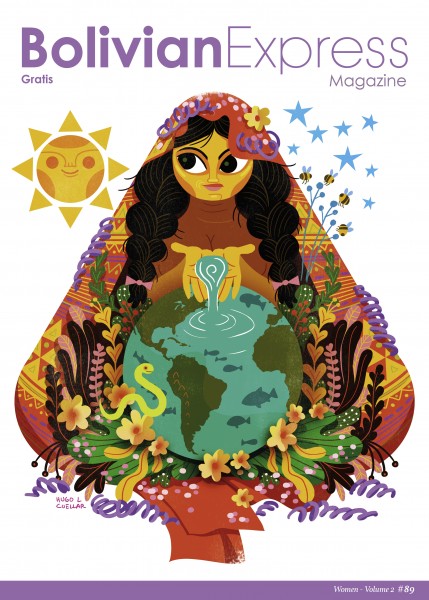

Illustration: Hugo L. Cuéllar

On 11 October, Bolivia celebrated the Day of the Bolivian Woman. The date – not to confuse it with International Women’s Day on 8 March – marks the birth of Bolivian poet Adela Zamudio in 1854, a fervent defender of women’s rights. The Supreme Decree establishing 11 October as a national celebration was approved in 1980 by President Lidia Gueiler, the only female president in Bolivia’s history.

Awareness days like this are important, as they can trigger debates and make people empathetic regarding certain issues. The month of October is also Breast Cancer Awareness Month, for instance. But this 11 October, I was left with a bitter flavour in my mouth. As people were honouring their daughters, wives, mothers, coworkers and friends with roses, newspaper headlines kept announcing more women being murdered, beaten and abused. In fact, Bolivia’s situation regarding women is one of the most ambiguous in the region, if not the world.

The following day, Página Siete, a La Paz–based newspaper, reported that 85 women were victims of femicide in Bolivia so far in 2018, and that 18,576 women had suffered physical abuse at home. These numbers are alarming because they are already higher than the data from 2017 (73 femicides cases in 2017). Reports from NGOs and international organisations also paint an sombre picture of the situation in Bolivia. Abortion is still criminalised, and the country has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the region, second only to Haiti.

There is a real contradiction in Bolivian society when it comes to the treatment of women. On the one hand, it is a society infused with machismo, something that Latin American countries share and that begins early at home when parents and grandparents – without necessarily realising it – start treating boys and girls differently. Machismo, as an intricate part of the home and the culture, directly affects Latina women and their development, and by extension affects society as a whole. This alone doesn’t explain the high rate of violence against women in the country, but it certainly is part of a bigger problem.

On the other hand, Bolivia has been making progress and is, at least politically, one of the most advanced countries in the world when it comes to equality in gender parity. The 2008 Constitution recognises the rights of women as a fundamental part of the structure of society, and a series of decrees protecting their rights have been promulgated. Bolivia is the leading South American nation in the inclusion of women in politics and has the second-most women-dominated Parliament in the world (after Rwanda), with 53% of the seats held by women.

Gender parity is a fundamental concept in the Andean cosmovisión, which can be found in the chacha-warmi (man-woman) philosophy. It refers to a code of conduct based on duality and complementarity which are considered the pillars of the family and of Andean communities. Men and women have to work together to create a successful home and society. But the reality of daily life for Bolivian women is quite different as these two extremes become intertwined and machismo remains a dominant force in women’s lives.

But the reality is not the same for every Bolivian women. Colla, camba, cochala, chapaca, chuquisaqueña, Aymara, Quechua, gay, trans, chola, gordita or whatever label one has, there is a multitude of identities and realities that intersect and cross over. Even among one category, one will find many layers. For instance, the iconic image representing Bolivian women in the world is the cholita with her long braids, multilayered skirts and bowler hat, but there are numerous types of cholitas, and reducing the Bolivian woman or cholita to just one word and one image is reductive and unfair.

We published our first women’s issue in July 2012, and we are now revisiting this topic in an attempt to further understand some of the realities that Bolivian women face today. But this doesn’t mean that we don’t have to think about them the rest of the year, or that the realities of Bolivian men are not as important. Like the Day of the Bolivian Woman which takes place once a year, this issue attempts to raise questions, open a debate, invite reflection and present a picture of who the women are that have built and are shaping Bolivia.

We are talking about your morning caserita, the police woman or the lady who comes to clean your house every week. This is about the girls you follow on Instagram and the (rare) women driving minibuses. And let’s not forget the most important woman of all: Pachamama, a.k.a. Mother Earth, the goddess of fertility who provides life and protection. She is still revered in traditional ceremonies and is sometimes syncretised as the Virgin of Candelaria.

The larger problem that women face here in Bolivia is still the reigning machismo. It can turn into violence and even femicide. Or it can be more subtle, such as the way your grandmother always gives your brother the nicer cut of meat while you are asked to clear up everybody’s plates and are expected to not have too much of an opinion and to be married with children by 30. Machismo is not just something that men impose on women; it’s part of society’s structures. Indeed, women can be just as macho as men – if not more so. The change will be slow and gradual, but as long as one can manage to avoid repeating the toxic and sexist patterns that start at home, it will come.

Photo: Marie de Lantivy

Valuing life and domestic labour

Bolivia is a melting pot of different ethnicities. It is home to women that belong to 36 different nations recognised by the country’s Political Constitution. Whether they are Andean, Amazonian, rural, urban, rich, poor, lesbian or heterosexual women, what all of them have in common is the vast amount of time they spend performing domestic tasks and caring for people inside and outside their homes.

The majority of Bolivian women, mainly those with a lower income, dedicate most of their time to domestic work and caring for family members. In general, this work is not remunerated and is thus invisible to the mainstream economy, where, according to local employment surveys, women are considered inactive. The lack of statistical information concerning this work inhibits the quantification of what these women contribute economically to the country.

The survival of the human species depends on our interdependence and on the decisions we make on a daily basis. At the centre of these decisions is the question of how families organise themselves in society to procure the resources they need and take care of their members. In a study called ‘The Economy of Care in Bolivia’, Elizabeth Zamora observed that Bolivian women, especially those from low-income demographics, bear the brunt of the weight of domestic responsibilities, which thwarts their participation in political and social life. Even when women have a larger participation in the labour market, they still allocate time to performing domestic tasks, which often results in women working double or triple shifts on a daily basis.

The care economy gives value to human energy dedicated to caregiving activities.

Amongst the set of tasks considered ‘domestic’ are those specifically related to the care of individuals. According to Zamora, the demand for care services in Bolivia is directed mostly to the younger population, which can be subdivided into three categories: children up to five years old, children from five to ten years old and adolescents. The most common care tasks in Bolivian households involve getting children ready for school, feeding them, watching over them, bathing them, etc. These tasks are almost exclusively delegated to women. They are carried out by housewives, mothers, grandmothers, older daughters, close relatives, or ‘trusted’ domestic workers.

Some women, mainly those from with a higher social status, choose to leave their jobs or work from home to have more time to care for their family. The majority of Bolivian women, however, do not have the freedom to make that choice, given the professional and financial risks it may entail. According to Zamora, if Bolivian women are not at home taking care of their children, the elderly or the disabled, they are working in hospitals, nurseries, social assistance centres or caring for their family members. These women do not choose how much time they want to devote to caregiving activities. The resulting responsibility leads to a loss of autonomy for women, which limits their economic development.

The concept of the care economy has its origin in feminist economics. The care economy gives visibility and value to the human energy that is dedicated to caregiving activities. These tasks can be thought of as services that are overlooked by dominant economic theories that focus on financial relationships. Shedding light on this issue has sparked a crucial debate on the role of caregiving services in a country's economy. The care economy puts these activities at the centre of the conversation. It recognises care as an indispensable pillar of society, acknowledging that without actions of care, societies would collapse.

We all have the right to be cared for and to care for others, but who should have that obligation in society?

Given the rigid gender roles in Bolivia, not all individuals who are economically active provide a service of care. On top of the issue of gender equality, the question arises: How can society meet the growing demands of care if more women are entering the labour market in a non-caregiving capacity? This is an increasingly relevant question given the growing demand for care services due to a growing aging population.

To address this imminent crisis of care, a set of institutions, advocacy groups and people committed to improving the living conditions of women in Bolivia, established the National Platform for Social and Public Co-Responsibility of Care in October of this year. Their objective is to create spaces for analysis and debate, as well as to formulate proposals and to develop strategies aimed at mobilising the State and civil society.

Given the rigid gender roles in Bolivia, not all individuals who are economically active provide a service of care.

This initiative aims at finding a balance between the role of the State, civil society and the market in guaranteeing access to quality care services. It is implied that women should not be exclusively responsible for providing these services. There are relevant examples of other social arrangement, such as the creation of child care centres, the extension of school hours for children to do their homework at school, care centres for the elderly and campaigns to encourage men to share the weight of caregiving tasks at home.

The premise for these actions is the need for the democratisation of care and the implementation of public policies that recognise the importance of caregiving in society. This means recognising our interdependence and making sure everyone can play a role in caring for others and being cared for themselves.

Photo: Marie de Lantivy

La Paz’s minibus industry is male-dominated, but female drivers are making inroads

If you live in La Paz, or are even just visiting, you will most likely take a minibus at some point. There are also micros (the large blue or yellow buses), trufis (taxis with a fixed route), PumaKataris (modern buses with fixed stops) and of course the cable-car system, Mi Teleférico. However, the minibus – actually a minivan – remains the most commonly used form of public transport in the city, as it covers the most frequented routes and allows its passengers to hop on and off whenever they want. It is also the cheapest mode of transport.

Every driver (and their minibus) is associated with a transportation syndicate that strictly regulate routes and represent the drivers. Minibus drivers tend to be men, of the 3,000 members in the Señor de Mayo syndicate, only five are women. We recently spoke to one of the syndicate’s female drivers, Maribel Cuevas, who has been a member of the Señor de Mayo syndicate for 11 years and was the first woman to join.

‘We need more women,’ Cuevas says. ‘Women are more attentive and patient while driving.’ Surprisingly, she says that it isn’t more difficult for women to work as minibuses drivers, as she didn’t feel like she had to prove herself more than her male colleagues.

People feel more secure when they jump into the minibus and see a woman behind the wheel.

So why aren’t there more female minibus drivers? Is it a dangerous job for women? Cuevas doesn’t think so, even when driving at night. ‘There are around 14 passengers with me,’ she says. ‘I think it is more dangerous for taxi drivers, because they are alone with the passengers.’ Moreover, she says that people feel more secure when they jump into the minibus and see a woman behind the wheel.

Perhaps there are so few women drivers because, in a society like Bolivia’s where gender roles are fairly inflexible, it’s just not practical. Cuevas works from four in the morning till seven at night. ‘It is not an easy profession,’ she says. ‘You abandon your family.’ Cuevas’s children are in middle school, and it’s her mother who takes care of them. But, she adds, sometimes the job gives her more freedom, because ‘you can go and come back from work any time of the day.’

‘I don’t have any regrets choosing to be a driver. I want to drive a bigger bus now.’

—Maribel Cuevas

Even if being a minibuses driver is not especially dangerous for women, and even if the job allows for more flexibility to manage one’s schedule, it is still a dominated by men – but this may change as long as women like Cuevas lead the way and show that it is possible. And Cuevas loves her job: ‘I don’t have any regrets choosing to be a driver,’ she says. ‘I want to drive a bigger bus now.’

The revival of old traditions is correcting misinformation about periods in Bolivia

Like many other countries, Bolivia is a place where menstruation is often spoken about only in hushed tones, and the topic can induce a certain shame among many girls and women. In Bolivia, however, myths and old wives’ tales about menstruation spread false information and contribute to the obscurity that cloaks the topic. Tales that have been passed down range from the amusing to the absurd, such as that eating mayonnaise will shorten the length of a period; that having sex while menstruating can cause harm to a woman (although this one’s quite global); that exposing menstrual blood to the natural elements can change the course of the weather; or that used sanitary products when mixed with other rubbish can cause cancer and other illnesses for the whole community – a particularly deleterious falsehood that interferes in women’s and girls’ participation in public life.

However, tides are changing. Since the mid-2010s, UNICEF, the UN’s children’s-health programme, has worked with rural communities in Bolivia to dismantle these myths through education and to promote menstrual health by providing school bathrooms. There’s also been a rediscovery of ancestral wisdom – through women’s circles and the use of plant medicine – that recognises the sacred function of menstruation and removes the shame of this near-universal female rite. Rocío Alarcón, a phytotherapist (plant-medicine practitioner), though, says that menstruation is still an oft-undiscussed topic. ‘A colleague and I began doing talks in schools about menstruation, and the girls would say, ‘Wow, I can’t believe they’re talking about this,’ she says.

‘To begin to break these stigmas depends on every one of us.’

—Rocío Alarcón

The shame that many women and girls share about the topic is countered by ‘giving them the assurance that [menstruation] is something very important and even sacred,’ Alarcón says. ‘There are still many mothers in our society [who say to their daughters when they are menstruating]: “How awful” [or] “You poor thing.” To begin to break these stigmas depends on every one of us.’

The big brands of female sanitary products exacerbate this stigma as well. ‘[Advertisements] say “Don’t get dirty” “Don’t stain,” and they also say to us, “No one can find out!”’ says Alarcón. These toxic ideas are further circulated by harmful products. ‘They also put other substances in these products like perfumes and, much worse, gels that absorb lots of fluid and convert into a jelly so you don’t stain,’ Alarcón adds. ‘But nobody says that skin absorbs as well, like a sponge, and these toxicities can stay in the body for up to months.’

Kotex, perhaps the biggest name in tampons and pads in Bolivia, ran a campaign earlier this year with the hashtag #EsosDíasDelMes (‘those days of the month’) including education programmes in schools with a publicity campaign featuring giant boxes of the company’s products for distribution. It was an admirable outreach campaign to normalise what is certainly normal for approximately two billion people, but, as Alarcón explains: ‘A lot of the time the women [in rural areas] have their own methods of managing their menstruation that they have been using for years, and then [companies] come and tell them to start using their products.’

An intersection between feminist discourse and environmental awareness is now propelling tampon and sanitary-pad alternatives into the mainstream. Menstrual cups are becoming increasingly popular in South America, with a number of South American brands having recently entered the market. Other alternatives like reusable cotton pads, though, have long been used in Bolivia, and Alarcón says that women can even make their own ‘from cotton fabric or even old T-shirts you no longer use.’

Menstrual cups are becoming increasingly popular in South America.

Bolivian women are reclaiming old traditions and honouring their monthly flow through conversation and collaboration on the topic – and by the use of modern products during menstruation. The women’s collective Warmi Luna Creciente even recently had its Encuentro Cultural Femenino at the Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, another step forward in removing the shame and secretiveness that has until now cloaked women’s monthly cycles. ‘[When we] speak between women,’ Alarcón says, ‘we support each other, we listen to each other, and it’s always very healing.’

Plant Remedies for Menstrual Cramps

Alarcón recommends making a tea by boiling fresh rosemary and/or oregano for no more than five minutes. Rosemary is a vascular plant that stimulates the menstrual flow, so for this reason it is recommended to drink up to three cups a day, one week prior to menstruation, up until the first day of bleeding. Use your thumb to measure the dose: six thumb lengths of rosemary for every three cups of tea. ‘The thumb helps us get a dosage for each person, because we all have distinct thumb sizes,’ Alarcón says. Use only plants that have been grown without pesticides. Chamomile can also help ease and relax cramps as well.

Download

Download