WOMEN - VOLUME 2

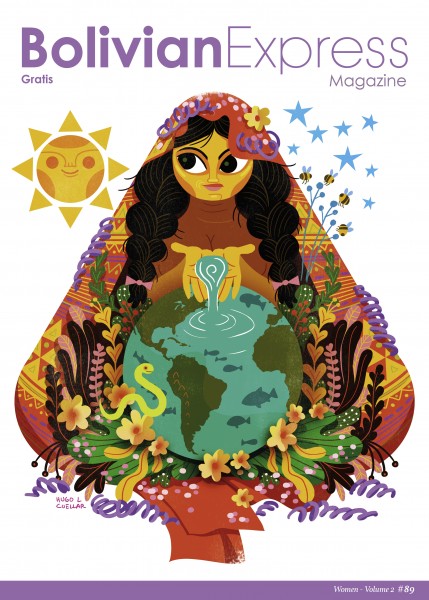

Illustration: Hugo L. Cuéllar

On 11 October, Bolivia celebrated the Day of the Bolivian Woman. The date – not to confuse it with International Women’s Day on 8 March – marks the birth of Bolivian poet Adela Zamudio in 1854, a fervent defender of women’s rights. The Supreme Decree establishing 11 October as a national celebration was approved in 1980 by President Lidia Gueiler, the only female president in Bolivia’s history.

Awareness days like this are important, as they can trigger debates and make people empathetic regarding certain issues. The month of October is also Breast Cancer Awareness Month, for instance. But this 11 October, I was left with a bitter flavour in my mouth. As people were honouring their daughters, wives, mothers, coworkers and friends with roses, newspaper headlines kept announcing more women being murdered, beaten and abused. In fact, Bolivia’s situation regarding women is one of the most ambiguous in the region, if not the world.

The following day, Página Siete, a La Paz–based newspaper, reported that 85 women were victims of femicide in Bolivia so far in 2018, and that 18,576 women had suffered physical abuse at home. These numbers are alarming because they are already higher than the data from 2017 (73 femicides cases in 2017). Reports from NGOs and international organisations also paint an sombre picture of the situation in Bolivia. Abortion is still criminalised, and the country has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the region, second only to Haiti.

There is a real contradiction in Bolivian society when it comes to the treatment of women. On the one hand, it is a society infused with machismo, something that Latin American countries share and that begins early at home when parents and grandparents – without necessarily realising it – start treating boys and girls differently. Machismo, as an intricate part of the home and the culture, directly affects Latina women and their development, and by extension affects society as a whole. This alone doesn’t explain the high rate of violence against women in the country, but it certainly is part of a bigger problem.

On the other hand, Bolivia has been making progress and is, at least politically, one of the most advanced countries in the world when it comes to equality in gender parity. The 2008 Constitution recognises the rights of women as a fundamental part of the structure of society, and a series of decrees protecting their rights have been promulgated. Bolivia is the leading South American nation in the inclusion of women in politics and has the second-most women-dominated Parliament in the world (after Rwanda), with 53% of the seats held by women.

Gender parity is a fundamental concept in the Andean cosmovisión, which can be found in the chacha-warmi (man-woman) philosophy. It refers to a code of conduct based on duality and complementarity which are considered the pillars of the family and of Andean communities. Men and women have to work together to create a successful home and society. But the reality of daily life for Bolivian women is quite different as these two extremes become intertwined and machismo remains a dominant force in women’s lives.

But the reality is not the same for every Bolivian women. Colla, camba, cochala, chapaca, chuquisaqueña, Aymara, Quechua, gay, trans, chola, gordita or whatever label one has, there is a multitude of identities and realities that intersect and cross over. Even among one category, one will find many layers. For instance, the iconic image representing Bolivian women in the world is the cholita with her long braids, multilayered skirts and bowler hat, but there are numerous types of cholitas, and reducing the Bolivian woman or cholita to just one word and one image is reductive and unfair.

We published our first women’s issue in July 2012, and we are now revisiting this topic in an attempt to further understand some of the realities that Bolivian women face today. But this doesn’t mean that we don’t have to think about them the rest of the year, or that the realities of Bolivian men are not as important. Like the Day of the Bolivian Woman which takes place once a year, this issue attempts to raise questions, open a debate, invite reflection and present a picture of who the women are that have built and are shaping Bolivia.

We are talking about your morning caserita, the police woman or the lady who comes to clean your house every week. This is about the girls you follow on Instagram and the (rare) women driving minibuses. And let’s not forget the most important woman of all: Pachamama, a.k.a. Mother Earth, the goddess of fertility who provides life and protection. She is still revered in traditional ceremonies and is sometimes syncretised as the Virgin of Candelaria.

The larger problem that women face here in Bolivia is still the reigning machismo. It can turn into violence and even femicide. Or it can be more subtle, such as the way your grandmother always gives your brother the nicer cut of meat while you are asked to clear up everybody’s plates and are expected to not have too much of an opinion and to be married with children by 30. Machismo is not just something that men impose on women; it’s part of society’s structures. Indeed, women can be just as macho as men – if not more so. The change will be slow and gradual, but as long as one can manage to avoid repeating the toxic and sexist patterns that start at home, it will come.

Illustration: Hugo L. Cuéllar

Bolivia has enshrined her rights into law

In December 2010, the Bolivian government passed Law 71, which recognises the inherent rights of Mother Earth, or Pachamama. It’s a curious political move today, when spiritual and religious content is usually stripped out of most nation-states’ legal doctrines. But 10,000 years ago, this wouldn’t be outside the pale. Indeed, during that time of agricultural development, many agrarian cultures worshipped a feminine earth deity. Fast-forward to the present day, and both Pachamama and Christian traditions are celebrated simultaneously in Bolivia in a syncretism of Andean and Catholic beliefs.

Ten thousand years ago, when humans were developing agriculture, many cultures worshipped a feminine earth deity.

Pacha means ‘time and space’, among other things, and Mama means ‘mother.’ In Andean cosmology, she is the highest power on earth and the offspring of the creator of the universe, Viracocha. Pachamama represents the feminine and fertility, and her husband, Inti, is the sun. Their sacred numbers are one and four, respectively, totalling five – the most sacred number in the Andean cosmovisión.

She is the highest power on earth and the offspring of the creator of the universe.

Photos: Sophie Blow/Adriana L. Murillo A.

Stitching the challenging road toward the rights of transgender Bolivians

In the hustle and bustle of the market in La Paz that leads to the city’s cemetery, it’s hard to miss Diana Málaga’s storefront. Bursting at the seams with vibrant designs inspired by the traditional chola dress, it’s difficult not to be drawn in by the staggering array of meticulously-sewn outfits on display.

Eager customers who step into the store, excited to get their hands on one of Málaga’s playful and creative spins on the traditional Bolivian dress, will find the store owner adorning sequins and beads to handmade garments ready to cater to the indigenous community of La Paz. Málaga is not only a successful designer and businesswoman with a degree in Social Communication, she is also the first transgender woman to identify as a chola.

Fashion has been more than a means for Málaga to express her passion for creative design. First and foremost, it was a means of survival, a way to pay the bills. Málaga turned to a career in fashion due to the intense gender discrimination in the workplace in Bolivia, which made it almost impossible for her to secure a well-paid job in the country ‘I have been unemployed,’ Málaga explained, highlighting the vicious circle of poverty that the transgender community faces in Bolivia due to a lack of education.

Málaga’s love for design has opened doors for her to speak to the press about her desire to eradicate public ignorance towards sexuality. As a university student at UMSA in 2001, she was forced to repeat a year of her studies after she legally changed her name. What should have been a simple administrative change, ‘took a year to be legally accepted,’ she says. ‘My fight has been hard, but, yes, I have won.’

Throughout her transition, Málaga has been unjustly criticised by onlookers who, blinded by ignorance about sexuality, undermine her claim: ‘I am a woman, I am going to have children.’ ‘Being a woman is not about having a vagina,’ Málaga explains. ‘Gender comes from your own self-awareness, your own brain.’ Bombarded with negative comments from relatives and strangers alike, Málaga never gave up the fight to be her real self, Diana María Málaga, ‘A transgender woman first and a chola second.’

Málaga drew public attention during her transformation as ‘the first transexual to identify as a chola.’ A chola (also known as a ‘cholita’) is usually associated with a traditional dress and a unique silhouette. The outfit typically consists of a small bowler hat, long plaits with tassled cords tied in a knot at the ends, a shawl and a large, ankle-length skirt that maximises the size of the hips and creates the desired silhouette. Being a chola, is more than just dressing the part. It is an integral part of a woman’s identity. It is away of life. As Málaga says, ‘A folklore dancer is not a chola.’ For these dancers, the traditional dress is part of a persona they recreate to give life to Bolivian cultural heritage.

A woman usually identifies as a chola by heritage. It is an identity that is passed down through the maternal bloodline. Málaga’s mother did not wear traditional dress like the women in the family who had come before her, but when her grandmother, a chola, invited Málaga to a party where she was to wear traditional dress, Málaga became inspired by this indigenous Bolivian look.

The decision to be a chola was a fashion choice, but ‘it started as a costume,’ Málaga points out. As a 1.78m tall transgender woman, she quickly became aware that it would be a real challenge to find a cholita ensemble for a woman of her stature. Before long, she found herself behind a sewing machine manufacturing her first pollera, a sombrero, a shawl and a complete cholita outfit. This was the start of Málaga’s journey of transformation as a chola. What started as a fashion choice quickly evolved into a core part of her identity as a Bolivian woman.

So what does it mean to be a cholita today in Bolivia? Following decades of racial discrimination, the word ‘chola’ has taken on pejorative connotations that echo Bolivia’s history of oppression towards indigenous communities. As a result, the term ‘cholita’ emerged, using the suffix ‘-ita’ in Spanish as a diminutive. Although ‘cholita’ is often considered a term of endearment for indigenous women, Málaga doesn’t see it this way. ‘I am not a cholita because it is a diminutive term, on a small scale,’ she says. Even though, the word ‘chola’ is largely considered a discriminatory term, Málaga has ‘worked hard to shape this word.’ Like her tireless efforts to protect the rights of the transgender community, she has also struggled for a future without prejudice towards indigenous people in Bolivia.

‘I want to make sure that nothing is impossible for transgender women.’

—Diana Málaga

Today, Málaga has a home and a husband to whom she has been married for seven years. She hosts a radio programme, has been interviewed on TV and hosts a television show on the channel ‘11 Red Uno de Bolivia.’ She uses her status within the LGBT community to provoke crucial discussions about prominent social issues in Bolivia, including domestic violence and human rights. She is a true icon in the LGBT community of La Paz, with a website that attracts visitors who eager to learn more about her journey as well as opponents to her cause.

So what’s next for Diana Málaga? As a woman with aspirations of securing greater rights for the transgender community in Bolivia, a move towards the world of politics could be in the cards. She hopes to effect change for the rest of her community by working tirelessly for gender rights in Bolivia and by fighting for greater public acceptance of all genders rather than settling for widespread gender tolerance. One of her main objectives for the future is to help redefine gender, not as a set of physical characteristics, but as an emotional and mental awareness of who you really are.

‘Gender comes from your own self-awareness, your own brain.’

—Diana Málaga

Miriam Rojas Ontiveras

Photo by Sergio Suárez Málaga

‘We have a lot of rights now, unlike before. I am very happy to be a Bolivian woman.’

Angela Abigail Calvimontes Pérez

from the Alalay Foundation

Photo by Marie de Lantivy

‘These girls have a lot of energy. When I cook with them we’re turning that energy into something positive.’

—Valentina Arteaga

Patricia Zamora

Photo by Sophie Blow

‘A Bolivian woman today is independent, capable of having a career. She can do the housework, look after her children but also study.’

Carlas Patzi

Photo by Ivan Rodriguez Petkovic

‘It is the woman who represents what we do. This is what we show, the entire woman. – with her essence… This is not only about the clothes – the mujer of pollera is not an item – this is about the woman.’

—Ana Palza

C. Sempertegui

Photo by Sophie Blow

‘Being a woman in Bolivia isa blessing. We have a veryunique culture, which issomething that not everywoman around the world cansay that they have’.

Download

Download