WOMEN - VOLUME 2

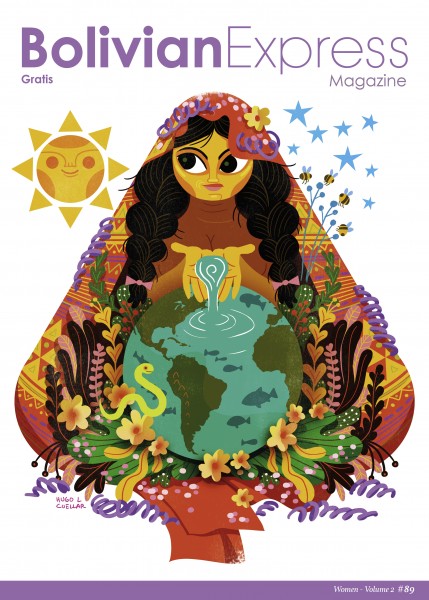

Illustration: Hugo L. Cuéllar

On 11 October, Bolivia celebrated the Day of the Bolivian Woman. The date – not to confuse it with International Women’s Day on 8 March – marks the birth of Bolivian poet Adela Zamudio in 1854, a fervent defender of women’s rights. The Supreme Decree establishing 11 October as a national celebration was approved in 1980 by President Lidia Gueiler, the only female president in Bolivia’s history.

Awareness days like this are important, as they can trigger debates and make people empathetic regarding certain issues. The month of October is also Breast Cancer Awareness Month, for instance. But this 11 October, I was left with a bitter flavour in my mouth. As people were honouring their daughters, wives, mothers, coworkers and friends with roses, newspaper headlines kept announcing more women being murdered, beaten and abused. In fact, Bolivia’s situation regarding women is one of the most ambiguous in the region, if not the world.

The following day, Página Siete, a La Paz–based newspaper, reported that 85 women were victims of femicide in Bolivia so far in 2018, and that 18,576 women had suffered physical abuse at home. These numbers are alarming because they are already higher than the data from 2017 (73 femicides cases in 2017). Reports from NGOs and international organisations also paint an sombre picture of the situation in Bolivia. Abortion is still criminalised, and the country has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the region, second only to Haiti.

There is a real contradiction in Bolivian society when it comes to the treatment of women. On the one hand, it is a society infused with machismo, something that Latin American countries share and that begins early at home when parents and grandparents – without necessarily realising it – start treating boys and girls differently. Machismo, as an intricate part of the home and the culture, directly affects Latina women and their development, and by extension affects society as a whole. This alone doesn’t explain the high rate of violence against women in the country, but it certainly is part of a bigger problem.

On the other hand, Bolivia has been making progress and is, at least politically, one of the most advanced countries in the world when it comes to equality in gender parity. The 2008 Constitution recognises the rights of women as a fundamental part of the structure of society, and a series of decrees protecting their rights have been promulgated. Bolivia is the leading South American nation in the inclusion of women in politics and has the second-most women-dominated Parliament in the world (after Rwanda), with 53% of the seats held by women.

Gender parity is a fundamental concept in the Andean cosmovisión, which can be found in the chacha-warmi (man-woman) philosophy. It refers to a code of conduct based on duality and complementarity which are considered the pillars of the family and of Andean communities. Men and women have to work together to create a successful home and society. But the reality of daily life for Bolivian women is quite different as these two extremes become intertwined and machismo remains a dominant force in women’s lives.

But the reality is not the same for every Bolivian women. Colla, camba, cochala, chapaca, chuquisaqueña, Aymara, Quechua, gay, trans, chola, gordita or whatever label one has, there is a multitude of identities and realities that intersect and cross over. Even among one category, one will find many layers. For instance, the iconic image representing Bolivian women in the world is the cholita with her long braids, multilayered skirts and bowler hat, but there are numerous types of cholitas, and reducing the Bolivian woman or cholita to just one word and one image is reductive and unfair.

We published our first women’s issue in July 2012, and we are now revisiting this topic in an attempt to further understand some of the realities that Bolivian women face today. But this doesn’t mean that we don’t have to think about them the rest of the year, or that the realities of Bolivian men are not as important. Like the Day of the Bolivian Woman which takes place once a year, this issue attempts to raise questions, open a debate, invite reflection and present a picture of who the women are that have built and are shaping Bolivia.

We are talking about your morning caserita, the police woman or the lady who comes to clean your house every week. This is about the girls you follow on Instagram and the (rare) women driving minibuses. And let’s not forget the most important woman of all: Pachamama, a.k.a. Mother Earth, the goddess of fertility who provides life and protection. She is still revered in traditional ceremonies and is sometimes syncretised as the Virgin of Candelaria.

The larger problem that women face here in Bolivia is still the reigning machismo. It can turn into violence and even femicide. Or it can be more subtle, such as the way your grandmother always gives your brother the nicer cut of meat while you are asked to clear up everybody’s plates and are expected to not have too much of an opinion and to be married with children by 30. Machismo is not just something that men impose on women; it’s part of society’s structures. Indeed, women can be just as macho as men – if not more so. The change will be slow and gradual, but as long as one can manage to avoid repeating the toxic and sexist patterns that start at home, it will come.

Photos: Iván Rodriguez Petkovic

Cholitas in the City of Light

The cholita, or the mujer de pollera, is an iconic representation of Bolivia and La Paz. Bolivian designer Ana Palza, who makes jewellery and clothes for mujeres de pollera, accompanied six cholita models to Paris for a three-day event organised by the Cartier Foundation in October. In an event space designed by famed Bolivian architect Freddy Mamani – whose cholets in El Alto have gained worldwide acclaim as of late – these women modelled traditional Bolivian clothing in the capital of haute couture.

Palza, who has created jewellery for 19 years, began to focus on cholita fashion about five years ago. She noted that most jewellry was too expensive to be worn by participants in La Paz’s extravagant Gran Poder – pieces were frequently stolen during the wildly chaotic celebration. Palza wanted to create a line of affordable but elegant jewellery. So instead of using gold or silver, she created pieces using of pearls, finding inspiration from the style of the cholitas. Palza then started making clothes after realising that there were no traditional cholita wedding gowns.

A cholet without a cholita is nothing if not incomplete. Thus the fashion show.

Palza’s collaboration with Mamani started six months ago when she was contacted by the Cartier Foundation to organise a fashion show with mujeres de polleras in Paris. The impetus for the show happened two years ago, when Mamani had been invited to build a cholet-style installation inside the Cartier Foundation’s Paris location. But a cholet without a cholita is nothing if not incomplete. Thus the fashion show.

The three-day event began with a traditional challa, a blessing ceremony performed by a Bolivian yatiri). The next day, the mujeres de polleras posed in the streets of Paris in their traditional raiment. On the third day, the fashion show took place.

The show was divided into five parts. The first showed the rural origin of the mujer de pollera, and how polleras used to be made with sheep’s wool. The second part featured vintage polleras made of cotton, less colourful than those worn today. Then Palza paid tribute to Mamani by exhibiting clothes against a background of photos of cholets by French photographer Christian Lombardi. The fourth part highlighted the vicuña – an undomesticated relative of the llama that produces some of the softest wool in the world – with old and new takes on the traditional Andean wedding shawl. The finale was a tribute to Gran Poder, the epic May-June paceño Andean Catholic celebration. For Palza, authenticity was essential. ‘We wouldn’t have played any morenadas from [the carnival of] Oruro,’ she said. ‘They had to be from Gran Poder.’ The head of Cartier described it as ‘full of seduction, charm, authority, but also freedom – very beautiful.’

Sandra Zulema Patzi Mayta, one of the models, was glad to have been able to show the fashion world how Bolivian women dress, but she said that she and her fellow models had to constantly remind people that they were not from Peru, but from Bolivia. She feels that cholitas in Bolivia still face discrimination. ‘Everywhere else, people want to take pictures with us, but especially in La Paz, we are not valued,’ she said.

‘This is not only about the clothes – the mujer of pollera is not an item – this is about the woman.’

—Ana Palza

When asked about the future, Palza is vague. ‘I don’t know, I am working gradually,’ she said. ‘I am not planning anything. I am not doing this to make money or to win – it is a real passion.’ She has been invited to Spain to show her designs, but unless she can bring genuine cholita models, she said she’ll decline. Her creations are for the mujer de pollera to wear, not for a model to appropriate. ‘If we travel somewhere, we are bringing the mujer de pollera with us,’ she insists. ‘It is the woman who represents what we do. This is what we show, the entire woman. – with her essence… This is not only about the clothes – the mujer of pollera is not an item – this is about the woman.’

Photo: Marie de Lantivy & Luciano Carazas

A rising female chef in Bolivia

We all know women who cook: mothers, sisters, grandmothers, the woman around the corner who makes api con pastel. Finding a female cook is easy, but finding a female chef? That’s another story. The culinary world is still a male-dominated space, even though these chefs usually talk about how following the recipes of their mothers.

But things are slowly changing. Not long ago I met Valentina Arteaga, the woman behind the WhatsCookingValentina Instagram account. Arteaga is a cooking teacher for children at the Alalay foundation, she makes videos of recipes for the food magazine Azafrán and is the owner and chef of a soon-to-open restaurant. Cooking has always been her passion. She studied in a culinary school in Peru for three years, interned at Gustu, worked as an intern for a year at a Ritz Carlton in the United States and completed a master’s degree in Spain.

Two years ago, Arteaga came back to Bolivia. At first, she wanted to open a restaurant, but the project seemed too complicated at the time. So she became a food consultant. Five months ago, she started her Instagram account, which has now more than 2,000 followers. In light of this quick success, she decided to launch her brand What’s Cooking Valentina, with the goal of doing something new, something that doesn’t exist in Bolivia. That’s how she started taking pictures of her meals in her kitchen, sharing recipes and writing about the places where she likes to eat.

Everything about her brand concerns Bolivian food and culture. It gives people from abroad an insider’s look into Bolivian cuisine and the local way of life. She shows the Bolivian way of cooking sopa de mani for example. She combines traditional products with non-traditional meals, like an avocado salad with roasted chuño, tomatoes, onions and a cilantro dressing.

‘Women need to empower each other to take the Bolivian gastronomy to another level.’ —Valentina Arteaga

Arteaga’s dream of taking her vision to the next level and opening a restaurant is close to becoming real. She recently found a place and says that in three or four months people will be able to sit at one of Phayawi’s tables. Phayawi ‘will serve Bolivian food, but I can’t tell you more, I am keeping it secret for the moment,’ she says. The concept of Phayawi (which means kitchen in Aymara) is also to prove to young cooks in Bolivia that, ‘there is a lot to do here… This is a moving country… Everything is yet to be built.’ A lot of her Instagram followers have asked if she thinks it’s worth moving back to Bolivia, to which she always answers ‘Yes, you should come back and invest in Bolivia.’

Teaching and sharing her love of cooking is equally as important to Arteaga. This is why she is involved with the Alalay Foundation where she gives cooking lessons to children. The purpose of the foundation is ‘to reverse the conditions of affective, economic, social and spiritual poverty for children and teenagers in high risks situations.’ She volunteers two times a week, one time to cook with the boys, and the other time to cook with the girls. In one of her lessons for girls she taught them how to prepare greek yoghurt with fruits. Arteaga not only teaches her students how to cut and select the ingredients. She also teaches them why it is important to have clean hands before cooking and to be polite and respectful to others. She takes the children to different restaurants so they can discover new types of food. The next visit in her lesson plan, for example, is a Japanese restaurant where her students can try sushi and other dishes for the first time in their lives.

Even though Arteaga is a rising chef in Bolivia, being a woman in a man’s world can sometimes be hard. A colleague once told her: ‘You are pretty, you are going to be successful,’ but comments like those only get on her nerves. One of the reasons she came back to Bolivia was to show people that women could be as successful as men in this trade. After all there are very successful female chefs in Bolivia, like Marsia Taha Mohamed, the current head chef at Gustu, or Gabriela Prudencio, chef at Propiedad Pública. Arteaga wants to inspire women, which she is already accomplishing through her Instagram account.

‘Women need to demonstrate they are capable of doing what men are doing,’ she says. ‘Women need to empower each other to take the Bolivian gastronomy to another level.’

-----------

Recipe :

• Soak your chuño (until is soft) and mote (white dried corn) in water a day before.

• Cook them separately in boiling water and strain both.

• Medium diced avocado and queso fresco.

• Cut cherry tomatoes in half.

• The most important part: a hot pan.

• Add a bit of oil and sear all the ingredients including the avocado.

• Salad dressing: Lime juice, olive oil, salt and pepper.

• Sear your meat with salt.

• Add dressing to this salad and enjoy this deli dish.

Photo: José Rolando Ruiz

It’s not all champagne and cavorting with models, but it’s still great gig

‘Blogger’ is a word so common nowadays that it’s hard to believe that less than five years ago most people in Bolivia had never heard of it before. Nowadays though, it has become an overused but highly misunderstood word.

A few years ago I slowly started to learn about what fashion blogs were. I became fascinated by the one-on-one vibe that bloggers had with their readers. The tips, the tutorials, the life hacks, the outfit inspiration – it was a real approach to fashion, none of that overpriced, unapproachable glossy couture I was used to seeing in magazines.

In my first year of blogging, I encountered only raised eyebrows, weird looks and lot of ‘A fashion what?’

The only problem I saw, was that most of the bloggers I followed were from the United States or Europe, so even if they wore affordable brands like H&M or Zara, most of the things portrayed in their posts were impossible to get here in Bolivia. That’s where it all started: I wanted to make fashion available to people like me – people that live in Bolivia, who live busy lives and want affordable fashion for real people. Thus, Pilchas y Pintas was born as a creative outlet where I could share fashion inspiration, tips and tutorials.

In my first year of blogging, I made nothing. Instead of being able to monetise my blog, I encountered only raised eyebrows, weird looks and a lot of, ‘a fashion what?’. I got used to having to explain exactly what it was I did every time I met someone new. Blogging was such a new industry that back then, even I wasn’t sure what this new ‘job’ was all about.

Of course, I didn’t see Pilchas y Pintas as a job until my third year, when I received an email from a possible client. It had finally come, the day when someone was willing to pay me for blogging. The excitement came along with many questions, like ‘How much should I charge?’, ‘How many posts would be required?’, ‘How many photos should I include?’. In the end, that first job ended up being tremendously underpaid and required much more work than it was worth.

It took me another couple of years before I began to really understand the amount of work we bloggers put into our content should never be taken for granted. Most of the time it is fear and self-doubt that make us forget that every blog post requires time to brainstorm, write, shoot, upload and promote.

The blogosphere has evolved and expanded quite a lot since when I started. When I began blogging there were only three fashion bloggers in Bolivia, today there are many more. Different styles and approaches to fashion have flooded our social media and it’s amazing to see that Bolivian people have become more interested in the content created by national fashion bloggers. We have evolved from being the weird girls taking photos in the middle of the street, to actual business women (and men) who have a voice in the Bolivian fashion industry. We share the latest trends, showcase the hottest stores and attend the biggest events. It’s quite amazing, if I dare to say so myself, but it’s not all fun and games.

The growth and demand for bloggers and influencers in the Bolivian fashion industry have opened many doors for us bloggers, but not all of those doors have nice prizes behind them. Like all small industries, blogging can be amazingly ruthless. There’s a lot of competition for likes and followers, to find the best photoshoot locations and to get the biggest clients. It can be very easy to get swept up into this cutthroat circle. Inevitably, this creates a lot of pressure, especially considering that blogging is usually a one-person job. If the blog does well, then hurrah for you. But if it does poorly, you are the only person to blame. Everything that happens, both good and bad, is 100 percent on your shoulders, and this can be a heavy weight to bear.

On the other hand, many clothing brands still don’t understand what bloggers are and how they differ from influencers or brand ambassadors. Even though they are eager to work with us, they still don’t quite get how to do it correctly. The idea behind fashion blogging is quickly misinterpreted and with this, the authenticity that fashion bloggers are used to being known for is starting to slowly fade away.

The excitement and popularity of fashion blogging grows as fast as a badly poured Paceña on a hot summer afternoon, but bubbles over just as quickly.

Like all things in Bolivia, the excitement and popularity of things grows as fast as a badly poured Paceña on a hot, summer afternoon, and then fizzes out just as quickly. People here get bored of fads and soon move onto the next one. But not all is lost, and even though the blogging trend might slowly lose its power, fashion (and non-fashion) bloggers who have a genuine voice and a true essence are here to stay. The key is to focus on useful and real content. Yes, there will be ads and publicity along the way, but as long as you don’t lose yourself in it, you should be fine.

Download

Download