The Andean cosmovision and Bolivia’s latest constitution are centered around suma qamaña, or ‘living well together’ – the concept that one has to live in harmony with others and nature. This is strongly reflected in the socioeconomic structures which preceded the arrival of the Spaniards and that still survive today in the Aymara and Quechua notions of economic and social relations. Ayni, mink’a, jayma and waki are some of these concepts, which are based on solidarity, reciprocity and a tightly connected community in which everyone supports each other. Ayni, for instance, is an Aymara word that signifies giving to one in need, and receiving back when needed – ‘the more you give, the more you have.’ Waki implies complementarity: ‘One lends the soil, the other the seed, and together something will grow.’

In Bolivia, sharing and being part of a community is essential; one doesn’t only drink from one’s own glass but shares it with the rest of the table; api con pastel is best enjoyed in the public square while sitting next to your friend, neighbour or complete stranger. When shopping at the market, the seller and customer refer to each other as caserita/o, creating an understanding, a complicity between the two that implies that each belongs. Even the street dogs seem to understand this; they band together in the streets of La Paz as if they were part of a family, sometimes going on dates, or talking a walk to the park with their friends.

Globalisation may seem like it could endanger this vision of the world, but the desire for social connection is one that is deeply embedded in our nature – not just Bolivians, but humans in general. One can connect through one’s art, or by helping another. In exploring this concept, in this issue we look at the NGO Pintar en Bolivia, which helps women who have suffered from abuse with art therapy to reconnect with their feelings. And we also learn about Natural Zone, Melissa Miranda’s organisation that creates a space for young professionals to grow while at the same time being conscious and aware of nature.

If anything, the world we live in allows us to find even more ways to connect: Bolivia and Japan are celebrating a 120-year relationship, epitomised by Wayra Japón Andes, a band that performs songs that are a fusion of Japanese and Bolivian sounds. Bolivia and Germany have also recently signed an unprecedented agreement to exploit the country’s lithium resources. And last month, Bolivia brought together 14 nations of South and Central America in the 11th edition of the ODESUR Juegos Suramericanos, during which over 4,000 athletes came to Cochabamba to represent their countries and unite fans in their love of sports.

And ultimately, that is what this magazine is about. Eight years ago, Bolivian Express was born out of a desire to reveal Bolivia to the world, to introduce an unknown, uncharted and wonderful culture to unsuspecting travellers. Eighty-four issues later, over 300 interns have walked through the doors of the BX house, and the programme has become much more than simply just a magazine. It’s evolved into a family, a bridge between Bolivia and the rest of the world. It’s a place where friendships are born and where lifelong connections are formed. It’s a form of waki: Bolivia provides the stories, and our journalists tell them to the world, bringing some of Bolivia back home with them but also leaving something behind.

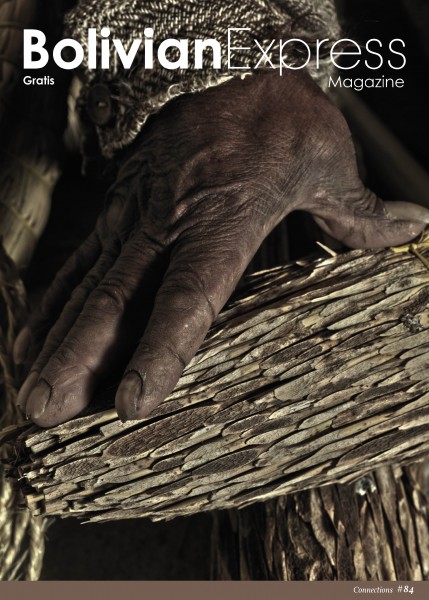

Photo: Ollie Goldblatt

Apathy, passion and the challenge of hosting the Juegos Suramericanos

For the first time since their inception in 1978, the Juegos Suramericanos are being held in Bolivia. The sporting event was created by the ODESUR (South American Sports Organisation) in 1976, with the aim of uniting South American countries in competition, and spreading Olympic ideals across the continent. Similarly to the Olympic format, the games take place every four years in various South American cities. After La Paz was the host of the inaugural games, Cochabamba won the rights to host the 11th edition in May 2016. Following years of investment and preparation, the games began on the 26 May.

In January of 2018 – a few months before construction for the games was completed – the hosting of the competition was estimated to cost 1.5 billion bolivianos, distributed across the construction of infrastructure, the purchasing of equipment and the training of the Bolivian team. Much of the investment was made by the Bolivian Ministry of Sports, although non-governmental aid also helped finance the event.

In previous editions, such as in Argentina 2006, Colombia 2010 and Brazil 2002, the nation that hosts the games has been victorious in the competition. Expectations were high in Bolivia, following the monumental investment the country had made and the anticipation felt after the Olympic games in Rio 2016.

I was struck by the lack of excitement regarding the games around the city.

Upon first arrival in Cochabamba, I was struck by the lack of excitement regarding the games around the city. Sparse and lonely indications of the sports event created an eerie effect, whilst the floods of foreign fans I expected to see did not appear. This is partly due to the short history of the event, which is celebrating only its 11th edition, but also to the cultural approach to Olympic sports (barring football) in Bolivia.

'Franco, for sure,' said a couple at a racquetball match when I asked them which athlete they were most excited to see. Racquetball is Bolivia's best chance for gold in this year’s games, as South American heavyweights don’t invest heavily in the sport due to its lack of Olympic status. Bolivia’s Conrrado Moscoso won gold in the men's singles this year. Sebastian Franco, from Colombia, whom Bolivian fans were most excited to see, represented their biggest challenge. Whilst racquetball fans would understandably be excited to see the best in the business, the lack of a competitive attitude in Bolivian fans was surprising. I asked another fan in attendance with his wife and four children which Bolivian athletes he was aware of: ‘None that are any good!’ he said. ‘I enjoy watching the sports with my family, and my kids. The result doesn't really matter to me.’

Perhaps the root of the issue doesn't come from the attitudes of fans. Such apathy could be born from the uncompetitiveness of the athletes. During the male’s volleyball Bolivia vs Argentina match, a mixture of Bolivian fans, drums and flags almost resembled footballing 'ultras.' As it became more and more clear, however, that the game would end in a Bolivian defeat, the ferociousness of their support slowly waned.

In contrast, Bolivian fans attended the women's basketball in masses, in which Bolivia was facing Chile for silver. The crowd of eager fans surrounding the stadium, unable to get in due to such a high demand, almost matched the number of fans inside the stadium. The energy they emitted as they watched their team storm to a comfortable win and a silver medal, suggests that a passion for sports is present in Bolivia and that fans will engage in sports in which Bolivia can challenge its South American rivals.

Raquel Justiniano, a member of the winning Bolivian team, shared her thoughts on the games: ‘My experience in this competition has been very beautiful, we received a lot of support from Bolivian people, and it’s something very positive for Bolivia’s sports.’ She attributed part of the success of the women's basketball team to the investment made in the country for the games, which allowed Bolivian athletes to train with a higher quality equipment and facilities suitable for an international competition. ‘[The standard of facilities] has improved a lot, we can see that they have worked with professional equipment of very good quality, that respects international standards. I hope they keep it for future tournaments,’ she said. Most of the infrastructure constructed for the competition will continue to be used in the following years, and in this sense the Cochabamba games of 2018 could be a catalyst for a steady increase in the competitiveness of Bolivian athletes, and consequently fan engagement in sports.

However, doubts remain regarding the effectiveness and appropriation of the Bolivian government’s investment. One notable absence from the list of participating athletes this year is national judo champion Martín Michel. Michel who omitted himself from the games as a form of protest against the lack of government support for athletes following the Rio Olympics. ‘After the 2016 Olympic games in Rio,’ he says, ‘I came back with the hope of receiving much more support, but none ever came.’

Michel hopes to represent Bolivia again in the future and has set his sights on the 2020 Tokyo Olympic games. This is why it speaks volumes that he has refused the opportunity to win on home soil due to the disenchantment with the Bolivian sports bureaucracy. The issues shrouding the current state of Bolivian sports appear to be largely financial: ‘The government offered $50 to cover my needs’, he tells me. ‘But in judo it costs $350 for a judogi, and we need two of them.’

This goes some way to explaining Bolivia´s minimal haul of medals, as financially Bolivia simply can't match the investments made by Brazil or Argentina. Bolivian athletes instead must hope for external sponsorships to aid their cause. Michel recognises this, but he suggests that Bolivia misdirected the investment in preparation for the 2018 games. ‘In Brazil, they invest $40 million in Judo. In Bolivia, $4,000. While the government is investing in infrastructure, the athlete is being abandoned,’ he claims.

‘My experience in this competition has been very beautiful... it’s something very positive for Bolivia’s sports.’

—Raquel Justiniano, Women’s basketball silver medal athlete

A greater focus on investment in Bolivian athletes, their equipment and their personal experiences would help prevent a feeling of apathy within Bolivian sports. However, a country usually enjoys the positive effects of hosting a major sports event many years after the event has taken place. The passion of the crowd of young girls sporting 'Cochabamba Judo' t-shirts whilst cheering on Bolivian female judo athletes resonated with me. The impact of the millions of bolivianos invested in the new judo arena will not be felt now, but rather in the years to come, for these young girls will now have access to greatly improved training facilities. Simply witnessing professional athletes representing their country will be an invaluable experience for them.

There is potential for improving this relationship between Bolivian sports and civilians. The foundations have been laid by the 2018 Juegos Suramericanos. Despite his harsh critique, Martin Michel shares this feeling of optimism and puts the emphasis on the authorities to dictate such an improvement: ‘The authorities have to want it,’ he says. ‘The state can put some of the money and the rest can come from private companies. Together they can do very good projects.’

Only time will tell if hosting the 11th edition of the Juegos Suramericanos will stimulate greater engagement in sports within Bolivia. The necessary passion exists on all sides: from the volleyball ultras, to the Ministry’s major investment. Bolivia will look to the 2020 Olympics and the 2022 Suramericanos to see such passion emerge and improve this year’s mark: 34 medals, 5 of them gold.

Photos: Iván Rodriguez

Traditional Japanese and Bolivian Music Fused Together

In 1899, Bolivia’s first Japanese immigrants made their home here. Next year, 120 years later, this historical moment is being reflected in music. Wayra Japón Andes, a band composed of five Japanese men who migrated to Bolivia to learn and play Bolivian music, are the first group of musicians to combine the sounds and techniques of both countries.

Japanese interest in Bolivian music is nothing new; in fact, Bolivian bands have toured Japan since the 1970s, and all the members of Wayra Japón Andes were inspired to explore Bolivian music in their teenage years whilst still in Japan. Guitarist Hiroyuki Akimoto and charanguista Kenichi Kuwabara joined Andean music clubs whilst at university, and Kohei Watanabe and Takahiro Ochiai were exposed to Bolivian instruments – the charango, and quena, respectively – from a young age.

The music of Bolivia was the defining factor in these musicians’ decision to migrate across the Pacific Ocean. Akimoto was enchanted by the culture upon arrival in Bolivia, and at only 18 years old he decided to remain for more than just the one year he planned on staying. ‘After a year, there were a lot of things left to study, more to learn, more people to meet,’ Akimoto says. ‘So I called my parents in Japan, and I told them that I wanted to stay longer.’ Kuwabara also arrived in Bolivia planning to stay only a year, in 2007, but was drawn back by the culture and ended up migrating permanently in 2011.

‘I wanted to come here and learn about the lives of Bolivians, how they live with this music.’

—Kenichi Kuwabara

For the individuals within the group, the culture they are exploring goes beyond music. Akimoto arrived in Bolivia in 2000. ‘I decided to come and see Bolivia with my own eyes, first only for one year,’ he says. ‘I listened to a lot of CDs of Bolivian music, and I liked the sound of the quena. There were some similarities with traditional Japanese music, and I have been playing it for the past 18 years.’ Similarly, Kuwabara migrated to Bolivia to study the culture around the music. ‘I am a charanguista, and in Japan I started playing,’ he says. ‘I wanted to come here and learn about the lives of Bolivians, how they live with this music.’

Wayra Japón Andes was formed in December of 2015. Before that, all members were in other bands playing traditional Bolivian music. Charanguista Makoto Shishido, who is based in Cochabamba, is a member of Los Kjarkas, the hugely popular Andean folk band. Other Wayra members have played with Anata Bolivia, Música de Maestros and Sumaq Wara – all traditional Bolivian music groups. Explaining how Wayra started, Akimoto says, ‘We are Japanese residents; this is our experience – why not try something new? We decided to do a musical fusion, Bolivian and Japanese.’ And it’s a distinct combination. The Andean sounds of the quena (a flute-like instrument) and the charango (an instrument similar to a small guitar) are pleasantly complemented by the three-stringed Japanese shamisen to give Wayra a unique sound. Even the band’s garb is a fusion: Japanese kimonos with aguayo embroidery.

Whilst the group's first album (Gracias Bolivia, released in 2015) contains mostly Japanese songs translated into Spanish, their upcoming second album (Viva Bolivia, to be released next year) introduces their experimental blending of Japanese and Bolivian sounds, and will include original songs. ‘The second album has two original songs already, written by us. In the first album, the ten songs are covers, with Bolivian rhythms. Some are anime and video-game themes: Dragon Ball Z, Super Mario Brothers – these are very well known in Bolivia,’ Akimoto says.

‘We are lovers of Bolivian music. Thanks to Bolivian music we have met here, and so we will dedicate our lives to the music.’

—Hiroyuki Akimoto

Watanabe is optimistic about the release of the group’s second album, mentioning the connection Wayra have made with the younger generation. ‘Young people are not listening to folkloric music, but they like music from anime, and we play that so they like it,’ he says. ‘So we are doing fusion. Hopefully, they can get interested in traditional folkloric music in the future.’ Ochiai exudes a similar sense of anticipation for the coming years, suggesting Wayra will look to combine Japanese and Bolivian cultures in more ways than just through music. ‘In any case, we are going to keep doing music,’ he says. ‘And we also want to do something cultural between Bolivia and Japan – like ambassadors.’

Late last year, a Japanese tour allayed the band’s concern about their fans’ reactions to their new musical direction. ‘We went on tour in Japan, in nine cities, and most of the rooms were full – they had about 200 to 300 people,’ Akimoto says. ‘And we were a bit worried because Japanese fans of Bolivian music have a certain image of the music that has to be like Los Kjarkas or Savia Andina. Our music is fusion, and it’s very different when it comes to instrument, melodies, language. However, Japanese fans of Bolivian music and people who knew nothing about it liked it the same.’

The group are keen to express their love for Bolivia through music, rather than just a simple love for Bolivian music. Such emotion can be felt lyrically and melodically in the new original songs of Wayra Japón Andes, and it perhaps explains the success and popularity of the group. ‘We are lovers of Bolivian music,’ Akimoto says. ‘Thanks to Bolivian music we have met here, and so we will dedicate our lives to the music.’

Photo: Jack Francklin

Its Cinematic Landscape and Culture Are Equal to No Other

La Paz, a city known for its beauty and unique cultural traditions, is pushing to become a set location for international films. In the coming weeks, a meeting will be held in the Bolivian administrative capital which will see leading international filmmakers come to the city to discuss its potential as a setting for film production, with the aim of propelling it onto the international stage. The meeting has been organised by a Bolivian-based audiovisual company called Bolivia Lab which promotes the country’s cinema presence to the outside world. Indeed, there are many reasons to suggest that La Paz has the qualities to be a success in the film market. Claudio Sánchez, who is in charge of programming, distribution and exhibition for Cinemateca Boliviana, describes the city as having the perfect light for making films. ‘Light is a very important factor in filming,’ he says, ‘and La Paz has a certain type of light that is different. Here there is a light that not only gives you creative liberties, but also demands much less in terms of the need for artificial light.’

‘Light is a very important factor in filming, and La Paz has a certain type of light that is different.’

—Claudio Sánchez

In setting out the advantages that La Paz has, Sánchez also recognises that, as with any city, it also has its drawbacks. He emphasises that productions need the knowledge of locals in order to discover filming locations and other amenities which would make filming in the city all the more special. Nonetheless, he explains that Bolivian and Andean culture is particularly welcoming to foreigners, and paceños would be amenable to guiding film crews around the city, overriding such concerns. Moreover, Sánchez notes that ‘La Paz has a long cinematographic tradition. I bet you that if you go out at this moment through the Prado there will be a film crew. No matter what happens today they will be filming.’

Other regions in Bolivia have had more involvement in the film industry, particularly Uyuni, which is the home to the magnificent Bolivian salt flats. But La Paz already has the infrastructure set in place to advance to the next stage of the cinematic industry. (For instance, new regulations make it easier for filmmakers to gain access to public services, such as the police or the firefighters.) However, Sánchez does acknowledge that La Paz is still only at an intermediate stage in its progress to become an influential location on the international filmmaking stage. But, however far off the city is from this objective, it is taking major strides to achieve this goal.

‘If you go out at this moment through the Prado there will be a film crew. No matter what happens today they will be filming.’

—Claudio Sánchez

What is evident is that La Paz has a distinct culture, tradition and mythical essence that would benefit many filmmaking ventures. And the what economic benefits that international film generates here will certainly be deserved and repaid in time, hard work and cultural influence when the film industry realises the exciting potential this wonderful city offers.

Download

Download