The Andean cosmovision and Bolivia’s latest constitution are centered around suma qamaña, or ‘living well together’ – the concept that one has to live in harmony with others and nature. This is strongly reflected in the socioeconomic structures which preceded the arrival of the Spaniards and that still survive today in the Aymara and Quechua notions of economic and social relations. Ayni, mink’a, jayma and waki are some of these concepts, which are based on solidarity, reciprocity and a tightly connected community in which everyone supports each other. Ayni, for instance, is an Aymara word that signifies giving to one in need, and receiving back when needed – ‘the more you give, the more you have.’ Waki implies complementarity: ‘One lends the soil, the other the seed, and together something will grow.’

In Bolivia, sharing and being part of a community is essential; one doesn’t only drink from one’s own glass but shares it with the rest of the table; api con pastel is best enjoyed in the public square while sitting next to your friend, neighbour or complete stranger. When shopping at the market, the seller and customer refer to each other as caserita/o, creating an understanding, a complicity between the two that implies that each belongs. Even the street dogs seem to understand this; they band together in the streets of La Paz as if they were part of a family, sometimes going on dates, or talking a walk to the park with their friends.

Globalisation may seem like it could endanger this vision of the world, but the desire for social connection is one that is deeply embedded in our nature – not just Bolivians, but humans in general. One can connect through one’s art, or by helping another. In exploring this concept, in this issue we look at the NGO Pintar en Bolivia, which helps women who have suffered from abuse with art therapy to reconnect with their feelings. And we also learn about Natural Zone, Melissa Miranda’s organisation that creates a space for young professionals to grow while at the same time being conscious and aware of nature.

If anything, the world we live in allows us to find even more ways to connect: Bolivia and Japan are celebrating a 120-year relationship, epitomised by Wayra Japón Andes, a band that performs songs that are a fusion of Japanese and Bolivian sounds. Bolivia and Germany have also recently signed an unprecedented agreement to exploit the country’s lithium resources. And last month, Bolivia brought together 14 nations of South and Central America in the 11th edition of the ODESUR Juegos Suramericanos, during which over 4,000 athletes came to Cochabamba to represent their countries and unite fans in their love of sports.

And ultimately, that is what this magazine is about. Eight years ago, Bolivian Express was born out of a desire to reveal Bolivia to the world, to introduce an unknown, uncharted and wonderful culture to unsuspecting travellers. Eighty-four issues later, over 300 interns have walked through the doors of the BX house, and the programme has become much more than simply just a magazine. It’s evolved into a family, a bridge between Bolivia and the rest of the world. It’s a place where friendships are born and where lifelong connections are formed. It’s a form of waki: Bolivia provides the stories, and our journalists tell them to the world, bringing some of Bolivia back home with them but also leaving something behind.

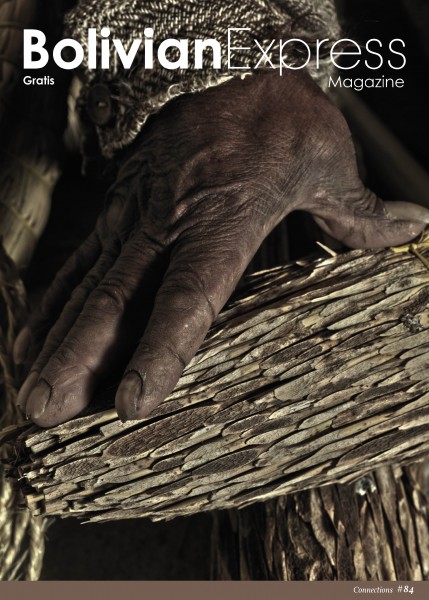

Photos: Katherina Sourine

Training young professionals in Bolivia to preserve the world we live in

For Natural Zone CEO Melissa Miranda Justiniano, the attainment of knowledge has always been at the forefront and heart of her endeavours. As a young woman joining the workforce, she found that her passion for learning and development, especially in relation to environmental conservation, was often held back by a repressive work climate for young professionals. Despite cultural setbacks, her motivation for becoming an entrepreneur with a higher purpose to benefit and conserve the environment, led her to push through the tumultuous path that ultimately birthed the organisation Natural Zone. ‘My idea of entrepreneurship has been focused on finding a friendly environment for young professionals, especially women,’ she says. ‘Because at the end of the day, we are all equal. We only need the opportunity that allows us to demonstrate our abilities, as well as generate experience.’

As an organisation that emerged from a set of principles, Natural Zone tackles the ambitious goal of positively shaping the attitude and competency of young professionals in Bolivia, 80% of whom are women, providing them with opportunities to develop an understanding of environmental fields. The motto of Natural Zone, Reintegrating you with our environment, concisely summarises its objective. Its core value states that society as a whole, not only professionals who specialise in ecological topics, can and must develop an understanding of how contemporary environmental issues affect communities. Natural Zone emphasises each individual’s personal role is in conserving the ecosystem we live in.

Its motto, Reintegrating you with our environment, concisely summarises Natural Zone’s objective.

The organisation researches issues such as pollution treatment, biological diversity, technological development, and the socio environmental status of various Bolivian communities and then divulges its findings through workshops and other activities. ‘We break the schema that this information exists only for scientists and we share with all to motivate people to want to know more,’ Miranda explains.

According to newly-employed researcher Natalia Chacón Flores, the values on which Natural Zone was established have not been lost through its years of development. Chacón began working as an intern at Natural Zone last year and became an official employee in 2018, joining the team that has now expanded to five permanent staff members.

‘We break the schema that information exists only for scientists and we share with all to motivate people to want to know more.’

—Melissa Miranda Justiniano, CEO of Natural Zone.

After attending a conversatorio held in the Natural Zone office in Sopocachi, La Paz, it became clear to me that Natural Zone thrives as a grassroots level organisation, which aligns well with their main objective. The workshop, facilitated by Chacón and attended by about ten people, began with a presentation outlining information on the topic of plastic, its role in Bolivia and its effect on the environment.

The group later split into smaller teams and discussed possible alternatives to plastic within frequently bought products, as well as ways to control the pollution of plastic materials in bodies of water. They then came together to assess the effectiveness of these alternative methods through the lenses of economic capability, available resources, and ability to be adopted within Bolivian society and culture.

Madelaine Guevara, a young woman who attended the workshop, explained the importance of being active in learning about the environment for her career. After studying Chemical Engineering at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, she worked at the supermarket Ketal in the field of quality control. But since the field of engineering is so large, Madelaine believes there are opportunities to work in sub-areas such as petrochemical, industrial and environmental engineering. ‘I think that Natural Zone has expertise in teaching about the environment,’ she says. ‘In Bolivia few institutions are dedicated to developing these topics.’

Some of the most significant obstacles Natural Zone faced in the onset was networking with professional organisations and providing information to the public. Alejandro Ticlla Espinoza, who introduced technological tools to the organisation has been pivotal in developing the business. He met Miranda in 2012, and they both quit their jobs in 2016 to launch the organisation. ‘We decided we had to do things by our principles, our dreams and what we want to create,’ Miranda explains.

Miranda praises the staff members of Natural Zone, explaining that the multidimensionality of their work demands individuals from a diverse range of fields who can work collaboratively. The diversity of the group ultimately benefits their training and workshop dynamic.

While technology has already played a pivotal role in making Natural Zone accessible to the public, according to Espinoza, it will continue to be instrumental for its future expansion. ‘One of our goals is to reach areas of Bolivia beyond La Paz, like Cochabamba and Santa Cruz,’ he says. ‘Beyond providing our training, we want to encourage local research and the accessibility of free, public knowledge.’ Although Bolivian society lacks motivation and access to local research, Espinoza believes there is opportunity for development.

‘Why not in Bolivia?’, he asks. ‘We can contribute many things. Bolivia is one of the most biodiverse countries in Latin America, so we have to take advantage of this in order to generate new paradigms in science.’ Although Bolivia’s diversity of communities and ecology can generate conflicting interests, Espinoza, Miranda and their team believe that Bolivia’s resources hold great potential.

Photo: Iván Rodriguez

The ongoing quest for a lithium-fueled future

German company ACI-Systems GmbH has invested in Bolivia’s lithium processing industry with hopes to cash in on the electric car boom. Bolivia’s decision to partner with the foreign firm has raised doubts about whether the company can live up to its promises, along with concerns surrounding the environmental impact of extracting from the world’s largest salt flat.

The nationalised Bolivian State Lithium Company (YLB) chose ACI-Systems to develop the industry in April of this year, turning down offers made by investors from China, Canada and Russia, who were also interested in the reserves. The $1.3 billion investment will allow Bolivia to process lithium brine from the Salar de Uyuni and manufacture electric car batteries for European markets.

At least two subsidiaries of YLB came together with ACI-Systems to form a joint venture, in which the national company will maintain a 51% stake, thereby keeping majority control.

According to Juan Carlos Montenegro, the head of the Bolivian state owned company, ACI-Systems will produce lithium batteries in Bolivia as soon as 2020, with a projected $1 billion a year in net profits. The plant is slated to initially produce 5,000 metric tons annually with future plans to scale up production.

The $1.3 billion investment will allow Bolivia to process lithium brine from the Salar de Uyuni and manufacture electric car batteries for European markets.

This isn’t the first time a lithium development project has been undertaken by a German company in Bolivia. The German firm K-UTEC Ag Salt Technologies operated a lithium carbonate pilot project in Uyuni from 2015 to 2017. Still, compared to neighbouring countries like Argentina and Chile, Bolivian lithium development has been slow. In over nine years of extraction, Bolivia’s operation has only managed to produce 10 tons of lithium monthly. The new partnership will substantially increase production capabilities and propel national economic development.

Juan Carlos Zuleta, a Bolivian lithium analyst, argues that Germany might not be the best partner. Zuleta argues that Germany lacks the technology to allow Bolivia to profit from its lithium reserves. ‘It neither constitutes the most competitive country in the production and sale of electric vehicles,’ he says, ‘nor is it the best potential partner for Bolivia to develop its energy lithium value chain.’ As Zuleta notes, ACI-Systems has no previous experience in mining projects of this calibre or in manufacturing lithium cathode batteries. He cites the company’s lack of international recognition, along with doubts about the profitability of the German market, as reasons to question the partnership’s potential to create economic growth in Bolivia.

Yet, in a statement made to Americas Quarterly, ACI-Systems says that the Bolivian government never intended to find a company that was in the biggest markets. Instead, it was aiming to fill the gaps in its current value creation capabilities. The company promises to bring much needed infrastructure, including technology and job training.

The investment, while allowing for technological development, will also bring in 1,200 direct jobs to the country. If the deal lives up to its lofty promises, thousands of indirect jobs could also result from the increased lithium production.

While electric cars running on lithium batteries are an environmentally-friendly alternative to gasoline and diesel engine vehicles, the process of producing the batteries themselves isn’t as green. Increased extraction from the pristine white flats will require vehicle traffic and a reliance on local water supplies as the process relies on evaporating water from the brine. Although the plant will not use local drinking water, its operation will require tapping into nearby source-water. In its statement to Americas Quarterly, however, ACI-Systems spoke up for the Bolivian government, emphasising their commitment to extract the resource in an environmentally-friendly manner.

A local lithium analyst argues that Germany might not be the best partner.

As the Bolivian government and the German company try to ease concerns surrounding the potential for environmental degradation, Indigenous communities situated in parts of Bolivia, Chile and Argentina known as the ‘lithium triangle’, worry. But objections to salt brine developments aren’t new, with the Washington Post reporting in 2016 one protester’s statement: ‘We don’t eat batteries.’

With production ramping up, the environmental impact of mining the salt flats could be ignored. Following the lithium and electric car industry boom, desired jobs are expected to move into the area which may offset environmental concerns. As the lithium industry moves into Uyuni, only time will tell whether the German-Bolivian coupling will be fruitful.

Photos: Adrianna Michell

Basking in the sun, an unbothered boy.

‘Do you think this volcano could erupt anytime soon?’

This desert dog is ready for a duel anytime. Pictured here without his cowboy hat.

Lunch time.

Download

Download