The Andean cosmovision and Bolivia’s latest constitution are centered around suma qamaña, or ‘living well together’ – the concept that one has to live in harmony with others and nature. This is strongly reflected in the socioeconomic structures which preceded the arrival of the Spaniards and that still survive today in the Aymara and Quechua notions of economic and social relations. Ayni, mink’a, jayma and waki are some of these concepts, which are based on solidarity, reciprocity and a tightly connected community in which everyone supports each other. Ayni, for instance, is an Aymara word that signifies giving to one in need, and receiving back when needed – ‘the more you give, the more you have.’ Waki implies complementarity: ‘One lends the soil, the other the seed, and together something will grow.’

In Bolivia, sharing and being part of a community is essential; one doesn’t only drink from one’s own glass but shares it with the rest of the table; api con pastel is best enjoyed in the public square while sitting next to your friend, neighbour or complete stranger. When shopping at the market, the seller and customer refer to each other as caserita/o, creating an understanding, a complicity between the two that implies that each belongs. Even the street dogs seem to understand this; they band together in the streets of La Paz as if they were part of a family, sometimes going on dates, or talking a walk to the park with their friends.

Globalisation may seem like it could endanger this vision of the world, but the desire for social connection is one that is deeply embedded in our nature – not just Bolivians, but humans in general. One can connect through one’s art, or by helping another. In exploring this concept, in this issue we look at the NGO Pintar en Bolivia, which helps women who have suffered from abuse with art therapy to reconnect with their feelings. And we also learn about Natural Zone, Melissa Miranda’s organisation that creates a space for young professionals to grow while at the same time being conscious and aware of nature.

If anything, the world we live in allows us to find even more ways to connect: Bolivia and Japan are celebrating a 120-year relationship, epitomised by Wayra Japón Andes, a band that performs songs that are a fusion of Japanese and Bolivian sounds. Bolivia and Germany have also recently signed an unprecedented agreement to exploit the country’s lithium resources. And last month, Bolivia brought together 14 nations of South and Central America in the 11th edition of the ODESUR Juegos Suramericanos, during which over 4,000 athletes came to Cochabamba to represent their countries and unite fans in their love of sports.

And ultimately, that is what this magazine is about. Eight years ago, Bolivian Express was born out of a desire to reveal Bolivia to the world, to introduce an unknown, uncharted and wonderful culture to unsuspecting travellers. Eighty-four issues later, over 300 interns have walked through the doors of the BX house, and the programme has become much more than simply just a magazine. It’s evolved into a family, a bridge between Bolivia and the rest of the world. It’s a place where friendships are born and where lifelong connections are formed. It’s a form of waki: Bolivia provides the stories, and our journalists tell them to the world, bringing some of Bolivia back home with them but also leaving something behind.

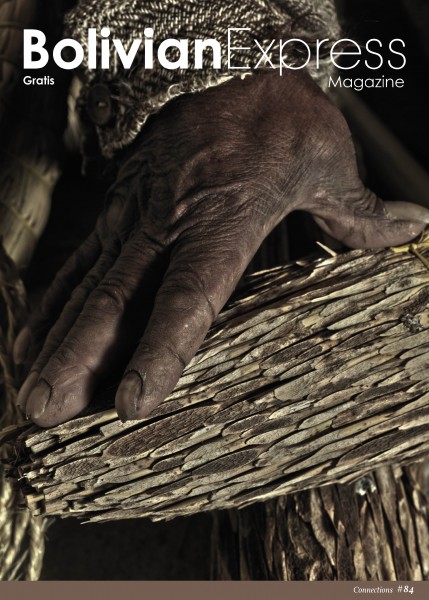

Photos: Iván Rodriguez

The Seasonal Festival Is Reinvigorating the Food Scene

On a sunny afternoon in the south of La Paz, visitors gather in Parque Bartolina Sisa in the Aranjuez neighbourhood. They’ve all been lured there by one promise: delicious food. Cuisines of different varieties, all interesting twists on classics from different cultures, are served to the bustling crowds. Tents and food trucks have been set up for the weekend – a visual reminder to the festival-goers to eat what they can now, because this weekend will soon be over and the trucks full of savoury treats driven away.

Festival attendees have co-organisers Micaela Molina and Catalina Roth to thank for the miscellany of food. The Eat Out La Paz Food Fest, now in its second year, has carved out a space for creative cuisine. The first of its kind in La Paz, the festival is slated to put the city on the map with food lovers at home and abroad.

The Eat Out La Paz Food Fest comes and goes with the seasons. Hosted once in the summer and once in the winter, it has grown from 40 to 60 vendors since it was founded. Originally set in a 1,200-square-meter car park, the event has expanded to permit 9,000 visitors this May. While the guests keep on coming, Molina and Roth are working hard to maintain an environment of healthy competition for the vendors. With 80 food purveyors at the previous Eat Out Festival, the duo learned that some weren’t getting their dues, and they reduced the number of participating businesses. Now the burger joints, crepe stands and coffee carts all get their fair share of attention.

‘La Paz is a place that has a lot of things to show. It is very important to export what we have. And there are a lot of tourists who come to La Paz just to eat – foodies.’

—Micaela Molina

The festival isn’t just for the restaurant giants either. Small and large businesses alike mingle at the park, all equally enjoyed by festival-goers. There are no large chains present, as the organisers want nothing to eclipse the local businesses and their development. Similarly, the location itself has been given room to grow; the Eat Out La Paz Food Fest has given the once near-abandoned park new life.

Still in its infancy, the festival has room to grow, and Molina and Roth are ready for it. After working in the marketing industry, the co-organisers wanted to try something new. Experienced working with brands, they wanted to create an experience for the city of La Paz that also benefits food vendors. While showcasing local establishments, the festival aims to engage locals and tourists alike. ‘La Paz is a place that has a lot of things to show,’ says Molina. ‘[It] is very important to export what we have. And there are a lot of tourists who come to La Paz just to eat – foodies.’

It’s clear that the organisers are keen to keep quality high and to mingle culture with food. The festival’s recent iteration, its third appearance on the gastronomic scene, also featured a musical performance from Jimmy James, a drink garden, and a screening of the UEFA Champions League final; while the food was what brought the guests there, the entertainment is what kept them.

While the festival-goers enjoy the event, the restaurants make it happen. The gathering allows businesses to grow and reach otherwise undiscovered clientele. Roth, offering a marketing perspective, says that the exposure is unmatched for up-and-coming eateries. ‘They bring new dishes, new textures, and people approve or not,’ she says. ‘It’s also a way for restaurants to renew themselves.’

Reflecting on past and future festivals, the goal is still the same for Roth: ‘[We] want to make a platform where there are different businesses – not only food, but music and atmosphere, and then do something different.’ While cooking up an enjoyable environment for festival guests, the co-organisers are determined to showcase to the world La Paz’s booming gastronomic scene. With creativity encouraged, the festival has seen fusion dishes that combine traditional Bolivian food with contemporary tastes. In order to settle the debate, Molina and Roth weighed in on which vendor was the festival’s best. Both favoured Chanchos a la Cruz, whose staff came all the way from Tarija to exhibit their slow-roasted pork.

‘We want to make a platform where there are different businesses – not only food, but music and atmosphere, and then do something different.’

—Catalina Roth

The organisers emphasise aesthetically pleasing stands that also adhere to their environmentally responsible standards. No plastic tables can be found at the venue, and no banners clutter the sky. The food has to speak for itself.

As festival-goers finish their drinks in the drink garden and begin to make their way home, they all have wide smiles and full bellies. The colourful garlands and lights have been dimmed, while the aroma of food, previously so fragrant, has faded away; the sun sets on the festival. Still, summertime will bring another gastronomic adventure.

Photos: Marion Joubert

The road to strength is paved with art

Who are these young girls, sitting quietly around a table and drawing animals that represent them? Who are these teenagers or mothers who escaped their home and eventually reached this women’s shelter?

It took a lot of courage for these girls to come to this women’s shelter in Cochabamba and start a new life, away from violence. Once they arrive, however, they have no clue of how to pursue a brighter future. Generally speaking, they enroll in the shelter lacking self-confidence, not knowing what to do with their lives, and unaware of their rights and personal qualities. But above all, they arrive with a good deal of trauma after having suffered some form of violence.

The NGO Pintar en Bolivia helps them overcome the difficulties they are facing through art therapy. The organisation helps them express their emotions and also assists them in building up their self-esteem and visualise their life objectives. It helps them answer the following questions: What do I want? What do I need? Who am I and how can I reach my personal goals?

The woman prompting these questions is Lisan Van Der Wal, a passionate art therapist from the Netherlands who is full of determination to make her Kallpa plan successful.

‘Kallpa’ means strength in the Quechua language. This is what the association aims at: to empower women who have been victims of sexual, psychological and physical abuse. To give them the strength to be independent and to overcome their problems. ‘That's why it is so important to give them a voice that they can raise,’ claims Lisan. The goal is to help open their minds and lead them to a better future.

The NGO Pintar en Bolivia helps vulnerable women overcome their difficulties through art therapy.

The Kallpa project consists in three sub-initiatives: the art therapy sessions, which take place on a weekly basis; the women empowerment days; and an annual exhibition that showcases the works of art that the girls have created.

The art therapy exercises take different forms depending on the skills of the volunteers who lead them. The week I visited Kallpa, the women were engaged in contemporary dance classes and drawing sessions, followed by a brainstorming exercise that helped them move forward with their therapy. The women empowerment days, which happen four times a year, focus on the girls themselves, on their life projects, and their hopes for the future. These days expand their horizons and give them the strength to do something worthwhile with their lives.

Lisan insists that the most important criteria for following the women’s progress is not the quality of drawings they produce, but the evolution of their personal process as well as the meaning behind their crafts.

The activities the women take part in have different purposes. Some are meant to encourage the women to discover their qualities and gain self-confidence, such as the ‘qualities cards’ workshop, which also reinforces the group’s social cohesion. In this game, the girls have to find three positive words that describe them. Then, one by one the women leave the room while those who stay choose three positive words or qualities that fit their peers.

‘Drawings are full of symbols that have their own separate language.’

—Lisan Van Der Wal, founder of Pintar en Bolivia

Other activities, such as the ‘heart full of feelings’ workshop invite the women to express their deep emotions. In this workshop, the women are asked to write a list of feelings they are experiencing in their lives, and assign a colour to each emotion. Then, on a sheet of paper, they must colour a heart-shaped space with the colours that symbolise what they are feeling. Once this is done, every woman who is participating in this workshop receives an empty glass bottle, which they paint with the colours of their emotions. Then, Lisan tells them: ‘We've worked on emotions, now I want you girls to go deeper: Which emotion is so intensely present in your heart that you can't even explain it? Write it on a paper and put it in the bottle so nobody can read it,’ she says.

In order to end the difficult and painful exercise in a positive way, Lisan invited the women to take a flower and slip its stem into the bottle as if to close it with the petals. ‘Your story is safe and belongs to the past now,’ Lisan told the women at the workshop. The goal of the activity was to increase self-expression, and to create a feeling of unity and respect in the group that helps them verbalise their feelings.

Lisan believes that art therapy is much more successful than usual therapy with these girls because art is in their traditions. It seems much easier for them to talk though art than with direct words. ‘Drawings are full of symbols,’ she explains, ‘that have their own separate language.’

‘I have noticed that in Europe,’ Lisan tells me, ‘art is only for people that are really good in it. In Bolivia, however, there is a lot of handicraft, everyone can do it.’ According to Lisan, art makes people think, learn, and express themselves. It can empower an individual. It is a solid tool for personal self-development and it can help us reflect on how people behave in real life. Thanks to the art therapy exercises, Lisan noticed the positive impact of art on the girls’ well-being: ‘They come from nowhere and I have seen so much progress!’, she says. There is indeed research that suggests that art is effective in reducing psychological troubles.

These favourable effects of art therapy are evident in the Kallpa project, which is only one of several programmes lead by NGO Pintar en Bolivia. The association also promotes the ‘Mariposa project,’ which lends moral support to sick children as well as their mothers in the pediatric oncological department of the Viedma Hospital. This Mariposa project aims to reduce their anxiety and make these young patients feel like children again. And last but not least, Pintar en Bolivia organises a project called ‘Nice Sunrise’ in collaboration with another NGO called Mosj Punchai. This initiative tends to children who have suffered severe burns in order to make them feel better and assist them in regaining their confidence.

‘If I wanna do everything I have in mind, I should stay here for ten years at least. It's definitely possible to change things here,’ Lisan says, when thinking about the future of her organisation. She has thousands of ideas on how to integrate art therapy in Bolivia and make it sustainable, but she remains is realistic and goes step by step to develop them successfully. Next year, she plans to launch a new project with schools in Cochabamba because she has noticed that the problems her organisation addresses could be prevented with a better education. Lisan Van der Wall wants to create partnerships with schools in the city to develop art therapy for young students and their parents on social and hygiene issues. Her goal is to counteract bullying against sick children and to fight against racism and discrimination in general.

This strong and determined woman reminds me of one of the drawings I saw during the workshop at the shelter: ‘Why did I draw a cat?’ asked the artist. ‘Because it is usually a nice animal, but when it has to defend itself, it doesn't hesitate to do so.’ Both the girl and Lisan are like the cat in the drawing: they can be really nice and helpful, but are willing to use their claws to fight for what they believe in, for a brighter future for the girls through the means of art therapy.

You can reach Pintar en Bolivia at: www.pintarenbolivia.org and support them here: www.kisskissbankbank.com%2Fen%2Fprojects%2Fpintar-en-bolivia-kallpa-project.

Image: Courtesy of Reinaldo Chávez Maydana

Combining Bolivian tradition and mystic symbolism, the artist captures the sublime

How can three simple dots – two for the eyes and one for the mouth – express so many different emotions? You might ponder this question yourself once you take a close look at the artwork of La Paz artist Reinaldo Chávez Maydana.

His paintings catch my attention because of a particular facial expression I notice in many of them. I ask Chávez about this. He explains that the figures are whistling. ‘They do it because they are happy,’ he says. The paintings I’m looking at represent the traditional Bolivian diablada dance. But those three dots that enthrall me are taken from El día de los muertos, an event which takes place on 1 November. For this holiday, which honours the dead, bakers make bread loaves in the shapes of many different figures. As a child, Chávez thought these figures were alive, with three dots for the eyes and the mouth. Now he incorporates this technique into his art, separating the faces with a line. Why this division? Chávez believes that contrasts are everywhere. ‘Night and day, good and evil, man and woman,’ he says. ‘This complementariness exists in human beings, in everything that exists in the world.’

‘I paint what I want, what impassions me.‘I paint because I love it.’

—Reinaldo Chávez Maydana

Our conversation goes on, and we discuss his abundant use of symbols. The majority of them, Chávez says, come from iconic elements of Bolivian culture, such as the masks from the morenada dance. I look at his paintings and I think I see Bolivia's soul in them—and I’m apparently not the only one to notice this. Organisers have recently asked Chávez to create a 70-metre-long fresco for La Paz’s iconic Gran Poder celebration.

But Chávez doesn’t just borrow from Bolivian traditions; he’s creatively inspired by many other things. He recently created a 40-part art cycle. His themes are various: pregnancy, women's sensuality, children, birds, landscapes and societal issues such as migration. He’s inspired by anything that gives him an emotional response, which he transmits through his art.

Chávez says his mother introduced him to this ‘magic world of colours’ at the age of 7, and his style has never stopped evolving by what affects him in his life. Discussing his art, he says, ‘You need to provoke something with your paintings. Art is not just about techniques or concepts, it's about emotions and feelings.’ Chávez says it was difficult, after attending art school at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, to break the rules he learned in order to be spontaneous in his work. His creative process is simple: He doesn't make any drafts, starting with a certain idea but remaining flexible with its execution. He might start to draw a couple, but if the shapes are different from his original idea, the painting could end up being a depiction of a child playing. He paints unpredictably, with passion. The strongest feeling which gives him inspiration to create, he says, is pain. ‘When you are happy,’ he says, ‘your passions go in other directions, to other people and activities.’

But that doesn’t mean he’s sad while painting. As an example, Chávez says that when creating a folklore-influenced piece, he’ll listen to traditional music and remember his grandfather, who used to dance at Gran Poder. He says he attains a feeling of freedom while creating his art. ‘I paint what I want, what impassions me,’ he says. ‘I paint because I love it.’

Chávez paints first for himself, he says, not the individuals who buy his work. His fans are Bolivians, but foreigners interested in unique folklore souvenirs from Bolivia have also noticed him. His art has travelled the world since 1998, with 30 exhibitions here and in the United States, Mexico, Argentina and Peru.

There’s one piece, though, that Chávez will not sell, that he keeps for his gallery. From his Flores desnudas series, it’s displayed at his gallery on Calle Sagarnaga. It explores folklore, sensuality, pregnancy and abortion, which is illegal in Bolivia.

Two figures, each depicted quite differently, dominate the painting. The first is a beautiful naked woman, exuding femininity and lost in thought. The other figure looks like a dangerous daemon, full of lust and looking like he wants to possess the woman. This painting, Chávez says, was inspired from stories about the morenada.

His artwork is a mixture of reality and imagination, while symbolising something deep and ethereal.

There’s a tragic backstory to the painting. A year and a half after the the painting was finished, the model who portrayed the woman died. Thus Chávez’s creation has a tragic side, giving it more depth, and it’s a way to pay tribute to his late muse. And it epitomises Reinaldo Chavez Maydana's style (even if he professes not to have one): a mixture of reality and imagination, while symbolising something deep and ethereal.

Download

Download